The Mandan Buffalo Dance is a ceremonial ritual observed in the modern era to honor the spirit of the buffalo and preserve Native American cultural traditions and was performed in the past for the same reasons just prior to the buffalo-hunting season or as the first part of the Okeepa Ceremony which was similar to the Sun Dance.

The Okeepa (Okipa) Ceremony was a New Year's festival during which participants awakened the Earth after winter and gave thanks for the gifts given by the First Creator. The Mandan Buffalo Dance was performed at the beginning of the Okeepa festivities to give special thanks for the buffalo, which provided the people with food, clothing, shelter, and tools. When performed as a stand-alone ritual, the Buffalo Dance was observed to honor the animal at the beginning of hunting season.

Like the Sun Dance of the Sioux and other nations, the Mandan Buffalo Dance and Okeepa Ceremony involved the entire community. The all-female White Buffalo Cow Society would perform the buffalo-calling ceremony to bring the buffalo to the hunting territory while the men would assemble the ritual area and the children would help clear the ground and, later, participate in symbolically driving away the spirit of famine.

Also like the Sun Dance, and other Native American religious rituals, the Buffalo Dance and Okeepa Ceremony were outlawed by the US government in the 1880s-1890s and could not be legally observed until 1978 after passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. When the Buffalo Dance is observed today, it is often as part of a larger Native American festival or public performance, although it is still enacted in private ceremonies.

The Mandan & Origin Stories

The Mandan are a Native American nation of present-day North and South Dakota related to the Sioux through the Siouan language but a distinct cultural entity. Their history, in fact, prior to and after the arrival of Europeans, included numerous raids on their villages by the Lakota Sioux who burned their villages. The name "Mandan" is an English term derived from "Mantannes" – the name heard by the French-Canadian fur trader and explorer Verendrye in 1738. The Mandan referred to themselves as Nueta ("we ourselves, we people") or Numakaki ("the people"). They are thought to have originated in the Mississippi River Valley and migrated at some point to the region of the Dakotas.

Mandan origin tales relate the story of Lone Man and First Creator (also known as Coyote) who agreed to divide the work of creation between them. First Creator made the lands south of the Missouri River and Lone Man the lands to the north, though this understanding depends on which version of the story one reads. In some versions, First Creator makes all the lands east of the Missouri River while Lone Man (the first human but with supernatural powers) makes tobacco, corn, and other people. An alternate storyline includes people coming up from underground, bringing corn with them or the arrival of Old Woman Who Never Dies or Mother Corn who provided those who had come up from the ground with corn.

After the creation was complete, the people seemed ungrateful, and so First Creator sent a flood to destroy them. Lone Man saved the people by building the Great Canoe and so restored creation after the flood waters subsided. At this point, either First Creator or Lone Man created new animals and plant life for the world, which included beans and squash (which, with corn, were the 'three sisters' of agriculture, the Native American staple crop) and, among other creatures, the bison/buffalo.

Importance of Buffalo & the Okeepa Ceremony

The buffalo provided the Plains Indians, including the Mandan, with everything they needed to live. The Mandan diet was supplemented by the 'three sisters', but the people primarily relied on buffalo meat for food and on every other part of the animal for other needs. Scholar Adele Nozedar writes:

The buffalo provided everything that the Native American needed for survival, and the list of uses to which the animal was put is impressive. The hides provided bedding, clothing, shoes, and the "walls" of tipis. The meat was good, nutritious food. The bones and teeth were used to make tools and also sacred implements. The hooves of the animal could be rendered into glue. Horns made cups, ladles, and spoons. Even the tail of the buffalo made a fly whip. The bones could be used to scrape the skin to soften it and was also fashioned into needles and other tools. Some tribes used the bone to make bows. The buffalo provided leather and sinewy "string" for those bows. Even the fibrous dung was used to make fires. The rawhide, heated by fire, thickened; this material was so tough that arrows, and sometimes even bullets, couldn't penetrate it, so it made an effective shield. This rawhide was used to make all manner of objects: moccasin soles, waterproof containers, stirrups, saddles, rattles and drums for ceremonial purposes, and rope. Rope could also be made from the hair of the buffalo, woven into tough lengths. Even boats were made from buffalo hide, stretched across wooden frameworks. (62)

As the buffalo was so important to the daily lives of the Mandan, it is no surprise that their most sacred ceremony opened with a call to the buffalo and the Buffalo Dance. The Okeepa Ceremony was observed to commemorate the salvation of the people by Lone Man and the restoration of the world – including the creation of the buffalo – and so the animal was central to the observance. Scholar Michael G. Johnson comments:

The ritual was a cosmic new year ceremony to ensure abundance of bison and a new beginning, involving collective – as opposed to individual – vision quests, and spiritual instruction and initiation for youths. (96)

Preparation for the festival began with the construction of a temporary lodge that would serve as the ceremonial center and the ritual cleansing and purification of the village. The lodge would be built with a hole in the center of the roof so that participants could look up at the sun. Those who would be participating would fast and refrain from sleeping or drinking for four days prior to the festival. The event began with the call of the bison by the White Buffalo Cow Society and then the Buffalo Dance – which lasted four days when performed on its own and possibly the same when observed as the opening for the Okeepa Ceremony.

Participants who had fasted and purified themselves entered the lodge and gazed up at the sun while their chests were pierced, and wooden pegs were inserted under the skin, which were attached to ropes whose other end was tied or looped over the top of the center pole of the lodge. While the men continued to gaze up at the sun, others launched them into the air, pulling them up by the ropes and suspending them while buffalo skulls were attached to their ankles to add weight and increase the pain.

The participants remained suspended, staring up through the hole in the roof at the sun, until the pegs ripped through their flesh, and they fell to the ground, or they fainted and were lowered down. The combination of a lack of food, water, sleep, and extreme physical pain, along with the long period of staring up directly at the sun, would make the participant receptive to a vision from the spirit world which would then be shared with the community for the greater good. Sometimes an endurance race completed the ceremony, possibly producing more visions, and then the people would give thanks through a communal, ritual feast.

Mandan Buffalo Dance

When the Buffalo Dance was observed on its own, as noted, it lasted four days and participants would, again, prepare through fasting and abstaining from water and sleep and purifying themselves through the sweat lodge. The Mandan believed that every individual had four souls: a white soul, a brown soul, a red soul, and a black soul. It is possible this belief originated in the story of White Buffalo Calf Woman who gave the gift of the Sioux ceremonial pipe and the seven sacred rites that informed their spiritual beliefs.

Although the Mandan were distinct from the original seven tribes of the Sioux, they would have known the story of White Buffalo Calf Woman who, as she departed, transformed herself into, first, a black buffalo cow then a red one, a brown one, and finally a white one before disappearing. Participants recognized the four souls by painting their skin black, red, and white, making the invisible world visible for the duration of the ceremony.

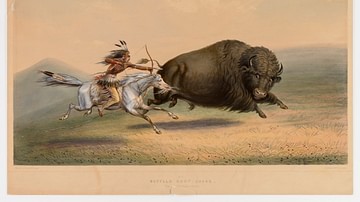

The ritual would begin with the eight dancers that had purified themselves dressing as buffalo as the drums began to beat. The details of the dance are given below by the Scottish folklorist and writer Lewis Spence (l. 1874-1955) in his Myths of the North American Indians (1914), but the details are almost certainly taken from the works of George Catlin (l. 1796-1872) a lawyer who abandoned his practice to become an artist and traveled among the Native American villages of the Plains and Prairies in the 1830s. Catlin's time among the Mandan is well-documented, and he was the first white man to describe the Okeepa ceremony.

The following text is taken from a reprint of Spence's piece in Voices of the Winds: Native American Legends by Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark:

Not too long ago, the buffalo was the principal source of food and clothing for the Mandan Indian tribe.

For these reasons, each year their tribe held a festival to honor buffalo. It became the chief celebration, a feast for all, marking the time for the buffalo's return. The buffalo-hunting season followed.

The most exciting event of the festival was the Buffalo Dance. Eight men participated, wearing buffalo skins on their backs and painting themselves black, red, and white. Dancers endeavored to imitate the buffalo on the prairie.

Each dancer held a rattle in his right hand, and in his left a six-foot rod. On his head, he wore a bunch of green willow boughs. The season for the return of the buffalo coincided with the willow trees in full leaf.

Another dance required only four tribesmen, representing the four main directions of the compass from which the buffalo might come. With a canoe in the center, two dancers, dressed as grizzly bears who might attack the hunters, took their place on each side. They growled and threatened to spring upon anyone who might interfere with the ceremony.

Onlookers tried to appease the grizzlies by tossing food to them. The two dancers would pounce upon the food, carrying it away to the prairie as possible lures for the coming buffaloes.

During the ceremony, the old men of the tribe beat upon drums and chanted prayers for successful buffalo hunting. By the end of the fourth day of the Buffalo Dance, a man entered the camp disguised as the evil spirit of famine. Immediately he was driven away by shouts and stone-throwing from the younger Mandans, who waited excitedly to participate in the ceremony.

When the demon of famine was successfully driven away, the entire tribe joined in the bountiful thanksgiving feast, symbolic of the early return of buffalo to the Mandan hunting grounds.

Conclusion

The Mandan are well-known in American history from the part they played in the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806. During the winter of 1804-1805, the explorers stayed in Mandan territory, where they met the Shoshone captive Sacagawea, taken in a raid by the Hidatsa, and her husband Toussaint Charbonneau, to whom she had been sold in a non-consensual marriage. Charbonneau and Sacagawea then became the party's guides and interpreters for the remainder of the journey west.

Long before the Lewis and Clark Expedition, however, and long before any European had set foot on North America, the Mandan had their own history, traditions, and rituals stretching back thousands of years, and, among these, most likely the Buffalo Dance – which was hardly a new innovation when it was observed by Catlin in the 1830s. The Mandan lived in permanent settlements of about 3,800 people characterized by distinctive domed houses and engaged in regular trade with their neighbors, fought off the Sioux and other nations, and were a prosperous community prior to their contact with Verendrye in 1738.

The community was comprised of 13 clans at that time, but, after the smallpox epidemic of 1781-1782, this number was reduced to seven. Smallpox was introduced to the community through European traders, and as the Mandan – like all the other Native Americans – had no immunity to European diseases, the death toll was significant. The 1781-1782 epidemic was only the beginning of their decline, however, as Johnson notes:

In 1837, the Mandan were destroyed by smallpox, with only 137 people being said to survive. These joined the Hidatsa and settled on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota, where a few descendants perpetuate their name. In 1906, they numbered 264, and in 1937, 345, but they are now largely merged with the Hidatsa. Together with the Arikara, they form the “Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation.” (143)

The Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan recovered, however, and established the 4 Bears Casino and Lodge on the reservation in 1993, creating jobs and generating income from tourists, and contributed to the construction of the Four Bears Bridge, the second largest in North Dakota, officially opened in 2005. The bridge and casino/lodge are named for the Hidatsa and Mandan chiefs, who were both known as Four Bears, and the bridge is ornamented with medallions honoring the histories of all three tribal nations. The Mandan, like all Native American nations, continue to keep their culture and traditions alive and the Buffalo Dance is often observed, not just by the Mandan but by other nations, both in private ceremonies and as part of the larger Sun Dance ceremonies or in public performances.