The Battle of Leipzig (16-19 October 1813), or the Battle of the Nations, was the largest battle of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), featuring over half a million soldiers and resulting in over 100,000 total casualties. The climax of the 1813 German campaign, the battle ended with the decisive defeat of French Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815).

The German Campaign

When French Emperor Napoleon I returned to Paris in December 1812, it was clear that his empire was in peril. The catastrophic failure of Napoleon's invasion of Russia, launched barely half a year before, had led to the loss of nearly half a million soldiers from disease, desertion, starvation, and battle; the greatest army France had ever produced had therefore ceased to exist, its components buried beneath the Russian snow. The Russian armies, not content with simply pushing Napoleon out of Russia, now crossed over into Poland, with the intention of ending Napoleon's dominance in Central Europe. To make matters worse, 200,000 French soldiers were still tied down in Iberia, fighting the British, Spanish, and Portuguese in the bloody Peninsular War (1807-1814). After the French defeat at the Battle of Salamanca (22 July 1812), the regime of Bonapartist Spain was left in a precarious position; before long, the Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese army would be poised for an invasion of France itself.

With his empire crumbling around him, Napoleon had to act fast. In almost the same breath that he announced the destruction of the Grande Armée to a shocked French public, he declared that he was raising a new army of 150,000 men to safeguard France from its enemies; by March 1813, he amazingly reached this quota of new troops, mainly through forced conscription. By this point, Prussia had joined forces with Russia; in the Treaty of Kalisch, signed in February 1813, each nation pledged to not make a separate peace without the consent of the other, beginning the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814). Intent on liberating Germany from the French emperor's grip, the Russo-Prussian army invaded Saxony, whose king was one of Napoleon's strongest German allies. Napoleon's army was not quite ready for battle – it was comprised largely of untrained recruits and had virtually no cavalry since most of Napoleon's trained horses had died in Russia. But Napoleon could not afford to waste any more time and set out for Saxony in April.

Despite the poor quality of his army, Napoleon proved to the world that he was still a force to be reckoned with. At the outset of the German campaign of 1813, he won two major victories over the Russo-Prussian army, first at the Battle of Lützen (2 May), then at the Battle of Bautzen (20-21 May). However, Napoleon's lack of cavalry prevented him from exploiting these victories, as the Allied armies were able to retreat from the battlefields to regroup. The Allies were nevertheless demoralized and asked Napoleon for an armistice. The French emperor, who desperately needed reinforcements, accepted, and the armistice went into effect on 4 June. Many historians consider this to be a blunder on Napoleon's part since he threw away the momentum gained after his previous two victories and allowed the Allies precious time to reassess.

The Trachenberg Plan

By now, the Sixth Coalition had been joined by Austria and Sweden, and the Allied leaders met at Trachenberg Castle to devise a new strategy to defeat Napoleon. In the resulting Trachenberg Plan, it was decided that three multinational armies would be created: the first was the 230,000-man Army of Bohemia led by Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg, a talented general who had been forced to fight for Napoleon during the Russian campaign. The second was a 140,000-man force dubbed the Army of the North and commanded by Swedish Crown Prince Charles John; prior to his election as heir to the Swedish throne in 1810, Charles John had been known as Jean Bernadotte and had been a French marshal in service to Napoleon. The third force was the 105,000-man Army of Silesia, led by Prussian General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, a fiery patriot who wanted revenge for the humiliating defeat Prussia had suffered in 1806. Each army contained multinational components, to prevent no single member nation of the Coalition from dominating the others.

The second part of the Trachenberg Plan was concerned with a strategy to defeat Napoleon. Since no Allied commander relished the thought of taking on Napoleon himself, it was decided that the Allied armies would avoid engaging any French force led directly by the French emperor. Instead, they would focus on attacking French supply lines and targeting smaller French detachments led by Napoleon's subordinates. In this way, the Allies hoped to whittle down Napoleon's army through attrition.

Bavaria's Defection

Hostilities resumed on 18 August, and the Allies put the Trachenberg Plan into effect. French Marshal Nicolas Oudinot, sent to seize Berlin, was intercepted and defeated by his old comrade Prince Chares John at Großbeeren (23 August), while another French marshal was defeated by Blücher at Katzbach (26 August). Things seemed to be going well for the Coalition until 26 August, when Napoleon outmaneuvered Schwarzenberg's Army of Bohemia and forced it to fight the massive Battle of Dresden (26-27 August). The battle was a French victory, and Schwarzenberg was forced to retreat after losing over 30,000 men; however, Napoleon's efforts to capitalize on his victory were once again frustrated, this time because the corps he sent in pursuit of Schwarzenberg was surrounded and defeated at Kulm (29-30 August). The survival of Schwarzenberg's army and the steady string of defeats suffered by Napoleon's marshals negated the gains won at Dresden.

As Napoleon found his plans frustrated at every turn, the member states of the Confederation of the Rhine watched events unfold with anticipation. A league of German states under Napoleon's protection, the Confederation of the Rhine had furnished Napoleon's army with troops in every campaign since its formation in 1806. Now, rising German nationalism and anxiousness over being on the losing side of the war caused several of these states to rethink their allegiances. On 8 October 1813, the Kingdom of Bavaria, once Napoleon's staunchest German ally, switched sides and joined the Sixth Coalition, with several other German states following suit. With the defection of Bavaria, Napoleon found his empire had begun to disintegrate before his very eyes. Only a decisive victory could save it now.

Preparations

With the three main Coalition armies bearing down upon him, Napoleon decided to abandon his plans to seize Berlin. Instead, he opted to march to Leipzig to protect his lines of communication. He ordered all his forces to concentrate around the city and, by 14 October, approximately 177,000 French troops had gathered in the vicinity of Leipzig. Meanwhile, Schwarzenberg's army was approaching from the south, while Blücher and Charles John were descending from the northwest. A fourth Coalition army, led by General Levin August von Bennigsen, was also closing in. The Allies had a total strength of around 325,000 men, though this number was quickly growing.

The battlefield of Leipzig was divided by the rivers Elster, Pleisse, Luppe, and Parthe, with the city itself sitting at the confluence of the Elster and Pleisse. The ground to the south of the city was covered in marshlands and woods, while the terrain to the west and north was flatter and more open, and the east was filled with ridges and interspersed with hamlets. Leipzig itself was defended by a wall of ill-repair, but the French had taken steps to fortify the city and its suburbs. All this gave Napoleon an excellent defensive position, but the French emperor had no intentions of fighting a defensive battle. He planned to send the bulk of his army, 130,000 troops, in a charge against Schwarzenberg's army between the Pleisse and Parthe rivers; the hope was that Napoleon could defeat Schwarzenberg before the other Allied armies had a chance to converge. The French spent the entire day of 15 October getting into position.

Meanwhile, in Schwarzenberg's camp, the monarchs of three of the great Coalition powers had gathered: Tsar Alexander I of Russia (r. 1801-1825), Emperor Francis I of Austria (r. 1804-1835), and King Frederick William III of Prussia (r. 1797-1840). Acting on the advice of the tsar, Schwarzenberg presented a plan where Blücher's army would attack from the northwest and a 19,000-men Austrian corps led by General Ignác Gyulay would threaten Napoleon's escape route to the west. The Allies' main attack would then be launched from the south, with the Russian General Mikhail Barclay de Tolly overseeing an assault on a series of villages (Markkleeberg, Wachau, Liebertwolkwitz), that made up the southern part of the French line.

First Day: 16 October

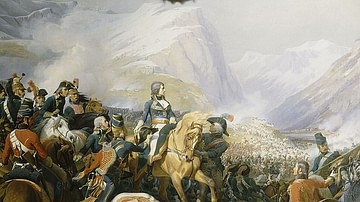

The battle began early on 16 October, which proved to be a dark and rainy day. On the southern sector of the battlefield, General Kleist's Prussian corps advanced along the Pleisse River and stormed the village of Markkleeberg, which was defended by Prince Józef Poniatowski's Polish troops. Brutal street fighting, made bloodier by racial hatred, lasted in Markkleeberg throughout the early morning, until Poniatowski's Poles were finally forced from the village; Kleist was prevented from pursuing by massed French artillery fire, which pinned the Prussians in Markkleeberg until after 10 a.m. Meanwhile, Allied troops led by Eugen of Württemberg seized the town of Wachau but were likewise pinned down by the French cannons. By 11 a.m., the momentum of the Allied attack on the southern front had died away, and Napoleon launched his own counterattack. 150 French cannons tore into Kleist's and Prince Eugen's troops as Napoleon ordered a general frontal advance.

Marshal Étienne Macdonald moved to threaten the Allied right flank and stormed the Kolmberg heights as marshals Poniatowski, Victor, Oudinot, and Augereau swept forward in dense attack columns. This attack was supported by Joachim Murat, King of Naples, who led 10,000 French, Italian, and Saxon horsemen in a thunderous charge, cutting Kleist's Prussian corps to pieces and chasing it as far as Crobern. At 2:30 p.m., General Bordesoulle led 18 French cavalry squadrons against Prince Eugen's infantry, driving a deep wedge into the Allied line. Two Allied battalions were shattered beneath the charge, and 26 guns were captured as Bordesoulle pressed on, nearly reaching Tsar Alexander's command post. This could have been the decisive moment of the battle, but Bordesoulle's charge was slowed by the marshy ground, and the French infantry had failed to support his attack. Bordesoulle was soon checked by the Russian Guard Cavalry, and the moment was lost; still, Napoleon seemed optimistic at this stage in the battle, writing to the King of Saxony that "all is going well" (Chandler, 929).

However, developments on the western and northern fronts would soon slow French momentum. In the morning, Gyulay's Austrian troops attacked the western suburb of Lindenau; since this threatened the French route of retreat, General Henri Bertrand's corps was dispatched to force Gyulay out of the suburb. Fighting in Lindenau lasted throughout the rest of the day and, while Bertrand retained control of the suburb, the fact that he was pinned down defending Lindenau meant that his corps was unable to participate in Napoleon's main attack. The French were similarly bogged down in the northern sector at Möckern, where Marshal Auguste de Marmont's corps was stuck fending off Blücher's army. Marmont commanded probably the best troops in the French army and was able to sustain wave after wave of fierce Prussian attacks. Eventually, Marmont saw an opportunity to rout the Prussian corps and ordered a charge; however, his cavalry commander refused to comply. Marmont was forced to launch the attack with his infantry alone, and his men were cut to pieces by Blücher's cavalry. Marmont was forced out of Möckern, and the Prussians seized the town.

With Bertrand and Marmont detained, Napoleon was forced to spread his attacks out too thinly. The momentum was therefore lost and most of the fighting began to fizzle out by 5 p.m. The first day of fighting had cost both armies horrendous losses; the French had suffered 25,000 casualties, the Allies 30,000. 17 October was quiet and saw no fighting, as both sides spent the day resting and gathering reinforcements. Yet the situation turned grave for the French when Bennigsen and Prince Charles John arrived, adding 145,000 additional men to the Allied strength; by contrast, Napoleon was able to gather only 14,000 reinforcements. After Napoleon's request for an armistice was denied, he began to make plans for a fighting retreat.

Second Day: 18 October

The Allies made plans for a series of six attacks against Napoleon; Blücher and Gyulay would renew their attacks on the north and west respectively, while additional attacks would be made on the key southern villages before the final blow against the French army in Leipzig itself. Napoleon, meanwhile, had shortened his line in preparation for a retreat. Fighting began in the morning, and initially went well for the French; Bertrand easily repulsed Gyulay's second attack on Lindenau, and Poniatowski's Poles successfully defended the village of Connewitz. However, the French were dealt a stunning blow at 9 a.m., when 5,400 of Napoleon's Saxon troops defected and joined the Coalition; the Saxons had fought under Charles John at the Battle of Wagram (1809) and still had affection for their old commander. The Saxons' betrayal seriously damaged French morale.

Confused and bloody fighting lasted throughout the rest of the day. The bloodiest fighting took place at Probsthedia, a village just southeast of Leipzig. Tsar Alexander took a personal interest in the capture of this village and ordered Barclay to seize it at any cost; wave after wave of Allied attacks broke against the French defense. A final assault, conducted by the 3rd Russian Infantry Division, managed to push into the village and destroy several French infantry units. However, the Russians were driven back by Napoleon's Imperial Guard. North of Leipzig, Marmont's 137 guns engaged in an artillery duel with 180 Allied cannons at Schönefeld; fighting here lasted well into the night, at which point Marmont was pushed into Leipzig. Blücher, meanwhile, reached the suburbs of Leipzig; it was during the battle for the suburbs that a British detachment fired their terrifying Congreve rockets, which had a powerful effect on French morale. By the afternoon of 18 October, Napoleon was almost out of ammunition and knew that the time had come to retreat.

Third Day: 19 October

At 2 a.m. on 19 October, the French began to withdraw; 30,000 troops led by Oudinot and Poniatowski were left in Leipzig to cover the retreat. The French had been unable to construct pontoon bridges, meaning the only route of escape was over a single bridge over the Pleisse River; the retreat quickly became chaotic, as ammunition wagons, cannons, livestock, women, soldiers, and the wounded all became crowded together. Still, the Allies did not realize Napoleon was retreating until 7 a.m. and did not mount an attack until 10 a.m. When the Allied attack did come, it was held at bay by Oudinot's and Poniatowski's troops, and the withdrawal continued at a steady, albeit slow, pace.

Then, disaster struck. Napoleon had ordered the bridge to be destroyed after the entire French army had crossed, delegating the task to one Colonel Montfort. Unwilling to be the last man out of the city, Montfort abandoned his post early, leaving the task of blowing up the bridge to a young corporal. At around 1 p.m., the corporal panicked and blew up the bridge prematurely, even though it was still crowded with wagons and people. Pieces of bridge, wagons, and body parts were blown into the air, as thousands of French soldiers remained trapped in Leipzig. Most of them surrendered, although several thousand troops attempted to swim across the rivers; Oudinot succeeded in this attempt, but Poniatowski, weakened from several serious wounds, drowned. Thus, the Battle of Leipzig came to an end. The Allies had won, at the cost of 54,000 killed and wounded. The French had only suffered around 38,000 battle casualties but had lost 30,000 additional men as prisoners after the bridge was destroyed.

Aftermath

The Battle of Leipzig hastened the decline of Napoleon's empire. The King of Saxony, one of Napoleon's few remaining German allies, became a prisoner shortly after the battle, and the remaining principalities of the Confederation of the Rhine defected to the Coalition. By November, the Confederation was no more, and the French Empire no longer had a presence east of the Rhine. Napoleon rushed back to France to prepare for a new campaign, but the fact that he had lost two armies in as many years permanently stained his martial reputation. For six months after Leipzig, Napoleon continued to hold out against the Coalition's invasion of France; however, the fall of Paris in March 1814 signaled the end, and Napoleon was forced to abdicate in April. He was exiled to Elba and the victorious Coalition met in Vienna to begin planning a post-Napoleonic Europe; of course, the Congress of Vienna would be briefly interrupted by Napoleon's return in the Hundred Days.

The Battle of Leipzig was the largest battle in European history prior to the First World War (1914-1918). It involved over half a million troops from across the European continent, produced over 100,000 casualties, and saw over 200,000 rounds of artillery ammunition discharged. The battle marked the reemergence of Prussia as a major power, and heavily contributed to Napoleon's downfall.