Abbeys were a striking feature of medieval urban and rural landscapes. Their layout and architecture reflected their purpose as cut-off monastic retreats which, conversely, also served and inspired their local communities. Although evolving over the centuries, many features of abbeys became standard, such as the main church, cloister, chapter house, refectory, library, calefectory, and dormitories.

The Growth of Abbeys

A medieval monastery was an enclosed and sometimes remote community of monks or nuns, led by an abbot or abbess, who shunned worldly goods to live a simple life of prayer and devotion to the Christian faith. Monastic communities first developed from the 4th century in Egypt and Syria and then spread throughout the Byzantine Empire and to Europe from the 5th century. The leader of these communities was called an abba, and it is from this word that the title of 'abbot' derives. The Italian abbot Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 to c. 543) is regarded as the founder of the European monastery model. The architectural design of abbeys, as the larger and more important monasteries became known, spread via travelling monks and through conquest, for example, William the Conqueror (c. 1027-1087) began rebuilding all English abbeys in the style of northern France from 1066 onwards, a process largely complete within a century.

The main idea of monasticism was that life in a place of quiet and relative solitude would better aid understanding of and permit greater proximity to God. Persecution of early Christianity also contributed to the idea of living in remote communities, hence many early abbeys were built on mountaintops, on remote islands, or on rugged coasts. Alas, this did not prevent them from being sacked during the 9th- and 10th-century Viking raids in Britain. By the High Middle Ages, which saw many monasteries rebuilt and extended, the opposite was true of their secluded beginnings as cloistered monastic communities had by then become fundamental to the secular communities living around them. Indeed, for many monastic orders, helping the local community was an important part of their mission.

Abbeys came to own and control certain geographical areas (typically being left land when benefactors died), with authority sometimes passed on to lower institutions within that area such as a priory (similar to but smaller than an abbey) or simpler monastery. The abbey's wealth came from rents paid on land it owned, donations, markets it might hold, tax reliefs, and the sale of goods it produced, which ranged from food to books. Even more rural abbeys eventually caused villages and towns to spring up around them as the wealth and services the abbeys provided created jobs and attracted visitors.

A large abbey like Cluny Abbey in France (founded c. 910) had as many as 460 monks, but a more typical abbey had around 100 permanent inhabitants. Most abbeys were either for men or women, but there were some where the inhabitants were mixed, notably the abbeys at Whitby in North Yorkshire, England, and Interlaken in Switzerland. The abbey was led by an abbot or abbess, and they typically held this position of absolute authority for life. An abbot or abbess had a second-in-command, the prior or prioress, who would also run subsidiary priories if that building was under the auspices of a nearby abbey. Senior residents were often given roles of responsibility, such as being in charge of the library or the wine cellar; these figures were known as obedientiaries.

Architectural Layout

The architecture of an abbey was very much inspired by the various roles its inhabitants had to perform. These roles were determined by the rules of their particular monastic order, but more especially by the approach of the particular abbot in charge, who held absolute power in the abbey. In addition, some orders were stricter than others; the Cistercians, for example, were required to make many more personal sacrifices than those belonging to the Benedictine order.

Factors affecting the particular architectural style of an abbey include the specific location – mountaintop monasteries like Meteora in Greece or the Benedictine abbey on the tidal islet of Mont-Saint-Michel in France were built like fortresses. There was, nevertheless, a remarkable similarity between abbeys in Europe and their prototypes seen in the Byzantine Empire, which were themselves derived from the ancient Roman villa. As the historian J. L. Singman explains: "Monasticism evolved with a degree of planning, coordination, and even deliberate standardisation that was not possible for secular institutions" (172). The Byzantine historian C. Mango gives the following summary of a typical Byzantine abbey-monastery complex, a model which was then copied more or less intact in the abbeys across medieval Europe:

It was normally surrounded by a wall and had a fairly elaborate covered portal, sometimes provided with benches. Beggars congregated here to receive alms from the monks. In theory, access to the interior was limited, young boys and members of the opposite sex being rigorously excluded. After passing the portal, the visitor found himself in a large open courtyard. In the middle stood the church visible from all sides…The living quarters were arranged all around, following the lines of the enclosure. The cells were rectangular and usually barrel-vaulted. Often they were built in two or more stories and had an open arcade in front of them. Next to the church was the refectory, which was either isolated or formed part of the residential rectangle. It was an elongated, apsed structure furnished with long tables and benches. Close to the refectory was the kitchen, with a raised hearth and an open domical lantern through which the smoke escaped. Storerooms equipped with large earthenware jars for keeping grain, pulse, oil, and wine were standard. Other subsidiary structures included a fountain, a bakery, a guesthouse, sometimes an infirmary, and a bath. (110)

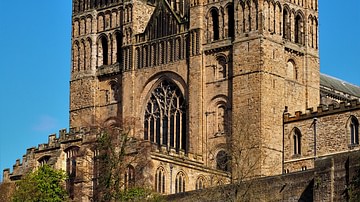

The architecture and plans of the early abbeys in Europe evolved from stone and timber Celtic complexes (6th to 8th centuries), through Carolingian-inspired cloister-centred layouts (9th to 10th centuries) and on to what became the standard model, the Norman abbey (11th to 13th centuries), all the while maintaining crucial architectural links to the ancestral Byzantine and Roman architecture. The Norman period saw a boom in monasteries of all kinds. Britain, for example, had around 50 monasteries at the time of the Norman conquest of England in 1066 but well over 500 by the beginning of the 13th century. As their wealth increased in the 13th and 14th centuries, so abbeys boasted even grander and more decorative buildings, often with features from Gothic architecture.

Building Materials & Decoration

An abbey was an impressive feature of the local landscape since it was one of the wealthiest and most powerful institutions in the medieval world. Abbeys were one of the few building types constructed in stone and made to large dimensions. Early abbeys used local stone or reused bricks from now-defunct Roman buildings, but as time went on, more wealth meant better materials could be used, like limestone and granite. If cut stone blocks were not used, then plaster-faced rubble was made to look like they had been.

Typical decorative architectural features of the abbeys of the High Middle Ages (with exceptions like the more austere Cistercian abbeys) include single or composite columns topped by a plain, cushion, scalloped or leafed capital. Buildings had archways (rounded in early versions, pointed in later ones), diminishing arches around doorways, blind arcades, battlements, mouldings, and carved coats of arms of the abbey's benefactors set above doorways and in ceilings. There were statues set in niches, chevron carved patterning, intricate tracery windows, and stained-glass windows – particularly lancets (tall triple or quintet panes with a pointed arch). By the 13th century, wooden roofs and ceilings were being replaced by stone rib vaulting supported by carved corbels (many of these are still visible today even in ruined abbeys) in the interior and lead-covered stone slabs on the exterior, which hid wooden support trusses underneath.

The Cloister

The cloister was the communal heart of an abbey or any other type of monastery. The name derives from the Latin word claustrum, meaning an enclosed space. The cloister is an arcade, usually columned, around an open square space (the garth) where access by outsiders was prohibited. The central space might be paved or contain a herb garden or water feature. Entry to the cloister was usually from a doorway in the northwest corner. Here in the cloister, the members of the order could talk freely, novices (trainee monks or nuns) and oblates (children in the care of the abbey) were taught, and chores were done, such as sharpening one's knife on the monastery's whetstone or washing clothing in large stone basins. Some larger monasteries had a lesser cloister which was reserved for quiet contemplation or silent work tasks. The largest cloisters are usually seen in Carthusian abbeys since this order was stricter than most. The Carthusians lived like hermits within an abbey complex and so had far fewer communal buildings. For them, then, the cloister was more important, since it was the only place where members of the order could spend any time together.

The Church

The church of the abbey joined the cloister and was usually built with a cruciform plan and laid out on an east-west axis, typically sited to block colder northern winds from directly hitting the cloister. The main and most decorated entrance to the church is usually on the west side. Here, there are often multiple doorways, tall lancet windows, perhaps a rose window, and many niches for statues of biblical figures and saints related to the history of the abbey.

Churches became increasingly larger and grander as the Middle Ages wore on. A progression can be mapped through Norman and then English abbeys. For example, the abbey at Jumièrges had a church with a nave of eight bays, Abbaye-aux-Dames in Caen had a nine-bay church, Ely Abbey's church had 13, and Winchester Abbey's had 14 bays. The wide nave allowed for large ceremonial processions to pass through and the public to sit if they had the right to enter the abbey for services. The east wing of the church also extended over time as choirs grew larger since it was here that the monks sat, and so, as abbeys grew in residents, the choir had to be larger. A screen separated the monks from the public sections of the church. The monks sat on wooden seats, which could be flipped up while they stood during a service; many of these can still be seen in larger churches today. Beyond the choir, and separated from it by a step, is the presbytery with an altar and fine stone paving. Behind the presbytery is the eastern end of the church, which might have a semicircular form (earlier) or square (later periods) and be decorated with tall stained glass windows which tell stories relevant to the locality, founders, or relics in the church's safekeeping. The relics themselves might be on display in the presbytery, sometimes with a small wooden loft structure set above them and into the wall so that a monk could stay there and ensure they remained safe while viewed by the public.

As the wealthy sought to ensure their comfort in the next life, they often left funds to abbeys so that a chanting of mass could be held regularly in their name. Sometimes, a memorial was built to the benefactor, known as a chantry, and this could take the form of a simple plaque, a special chapel in the side of the church, or even an entirely separate building.

The main church typically had a belfry tower to ring the abbey's services and call inhabitants to prayer. An obvious sign of an abbey's prosperity was to add or extend upwards an existing tower. At Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire, for example, a massive 170-foot (51.8-metre) tall tower was added to the north transept of the church in the early 16th century.

The Library

An abbey's library contained a large collection of books acquired through donations or produced by the monks themselves. There would also be certain ancient texts held in the abbey for safekeeping. Books were usually kept in wooden cupboards set in recesses on the walls. Abbeys were important centres of local learning, teaching the children of the wealthy and novices. Some abbeys gained a great reputation for education, such as Whitby Abbey, where many bishops were trained, including Saint John of Beverley (d. 721).

Writing and study work was done in a dedicated room, the scriptorium. Here, monks sat on stools and worked at high desks called carrels, which might be open or set in a cubicle. Illuminated manuscripts were painstakingly produced so that an abbey's library was always growing. Perhaps the most famous of all medieval manuscripts, the c. 800 Book of Kells, was once stored in the library of Iona Abbey on the west coast of Scotland.

Libraries and scriptoriums were usually built to face south to allow more light to enter, which also made them the warmest rooms to work in. Some libraries, such as in the abbey of Saint-Wandrille near Rouen in France, also included a royal archive. Women in the Middle Ages also copied and wrote books in abbeys, notably the German Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179). Unlike monks, the daily life of medieval nuns also included tasks of needlework, such as embroidering robes and textiles for use in church services.

Accommodation

Inhabitants of an abbey were supposed to put up with the bare minimum of comfort. Cells were simple since the inhabitants had very few private possessions. Dormitories (sometimes called dorters) were common, but novices and full order members did not mix. Beds typically had a straw or feather mattress and a few woollen blankets. In later periods, the dormitory might have been separated into wooden cubicles, each with a window, bed, and desk. The dormitory at Cluny had an impressive 97 glazed windows. Curiously, there was a rule at Cluny that no monk should sleep in darkness, and so the long dormitory was equipped with many oil lamps. Dormitories often had a staircase to access the church so that, if attendance at night services was required, it was not necessary to go out into the open air.

Carthusian monks lived in relative solitude in small individual houses with a fireplace, living room, study, workshop, and attached bathroom with a water tap. These small houses often had a private walled garden and were arranged around the cloister. The houses were certainly better than most in the outer secular world. Small hatches in the walls meant that food could be delivered by a servant, and the monks' solitude was left undisturbed.

By the High Middle Ages, lay brothers, hired labourers or serfs (unfree labourers), were employed by an abbey so that the monks or nuns could concentrate on ecclesiastical matters. Lay members of an abbey typically lived in their own accommodation block in an outer courtyard, which usually had its own kitchen, as here food could be prepared that the monks were not allowed to eat, like meat. Lay members grew fruit and vegetables, cooked, and cleaned. At the opposite end of the abbey's resident spectrum, there might be failed or disgraced politicians and nobles, obliged by their monarch to spend a secluded retirement in an abbey. Pilgrims and travellers might have a bed for the night in rooms or a building dedicated for this purpose, usually located to the west of the cloister so that they would not disturb the daily life of medieval monks. Distinguished visitors were often accommodated in palatial apartments in the main gatehouse. By the 13th century, many abbots had their own personal accommodation, which developed into an entirely separate building of increasingly grand proportions.

Refectory & Kitchens

The abbey was mostly self-sufficient for its food, as vegetables, fruit, and herbs were all grown in garden areas and orchards. Fish were kept and bred in the abbey's pond. Meat and other foodstuffs might come from outside lands managed by the abbey; such parcels of land with a farm were called granges. There was a kitchen, which was usually positioned near the refectory, but in order to prevent a fire getting out of hand and destroying the abbey, it might be a fully separate building (Glastonbury Abbey has a fine surviving example). In the latter case, a covered passage sometimes connected the kitchen to the refectory. The kitchen had various annexes, such as a scullery for washing dishes, a bakery and mill, a buttery, a wine cellar, a pharmacy, and a pantry for food stores (usually in a cool room under a larger chamber and called an undercroft). There was a brewery, making beer each week from wheat or oats since water was considered unsafe to drink. Some abbeys had a dovecote to keep pigeons, and these could be impressive buildings in themselves, taking on a square, circular, or polygon form with a high pointed roof full of stone niches for the birds to nest in the interior.

Inhabitants of an abbey usually had one main meal each day in summer and two in winter. Once prepared, the food was served in the refectory (sometimes called a frater), where everyone sat at long wooden tables and benches except the abbot and prior (plus any guests), who sat at smaller tables at the head of the room on a raised platform. In the corner of the refectory, set high in the wall and reached by a small staircase, was a wooden or stone pulpit where one member of the community would read aloud while their fellows ate.

Some abbeys had an additional refectory, the misericord, where meat was eaten (the name derives from 'mercy' as meat was a relaxation of many orders' strict diets). Most refectories had a stone basin (or lavabo) at the entrance for people to wash their hands before eating. The lavabo was fed water through a tap which released water from the storage tanks above. A small bell was rung to indicate the meal was ready to be served (and so was distinct from the church bell calling for attendance at services). The refectory was a large rectangular building, the one at Cluny:

...was a fine hall, well lit with thirty-six large glazed windows, and decorated with wall paintings that included scenes from the Old and New Testament, a large figure of Christ surrounded by the principal founders and benefactors of the monastery, and a description of the Last Judgement. (Singman, 175)

Refectories tended to be built along one side of the cloister, but as abbeys grew in size and so more space was needed for more inhabitants, the refectory was often turned 90 degrees and extended away from the cloister.

Sanitation

The washing and toilet facilities in an abbey were usually the best to be found anywhere in the medieval world. Toilets were usually connected to the dormitory and situated in a building called the reredorter. Cluny had a latrine block with an impressive 45 cubicles, each with its own window. The latrines typically emptied into a drainage channel through which ran water diverted from a nearby stream. Larger abbeys had a bathhouse, although inhabitants were not supposed to spend much time there, two or three baths per year being the norm unless the person was ill. Baths were typically made from large barrels.

Chapter House

Each morning an abbey had a chapter meeting when all the monks met to discuss the affairs of the monastery, hear confessions, and admonish any members of the order who had been lax in their duties. This meeting was held in the chapter house, which, therefore, had to be large enough to accommodate all the permanent residents of the abbey. Held around 8 a.m. each day, the meeting began with a reading of a chapter from the founder's rule book (hence the name) and would include the distribution of daily duties to each of the monks, who were seated on stone benches around the walls of the room. By the late Middle Ages, such buildings as the chapter house often had large glazed windows and ornate triple entrances.

Other Buildings

Next to the refectory building or below one end of it, an abbey might have a calefectory, which was the only heated room in the entire abbey (except the kitchens), designed to bring some relief from the harsh temperatures of winter. The fire in the calefectory was usually lit from 1 November to Easter.

An abbey often had many extra domestic and functional buildings where people permanently lived and worked to provide the monks with what they required. Abbeys were famous for providing medical care. An abbey had a hospital or infirmary with accommodation and a dedicated kitchen. Here, ill or more aged monks would be cared for. There was often a second infirmary for people outside the order.

Abbeys could also have stables and workshops where specialised craftworkers worked and lived, providing all the things the abbey needed from nails to glass windows. There were, too, dedicated spaces to give out alms to the poor (the almonry) and a room where negotiations and purchases could take place with traders from outside the abbey complex.

Finally, an abbey had its own cemetery, typically located to the east of the church and divided into two areas: one for those belonging to the order and the other part for wealthier members of the local community. Luminaries of the abbey, such as the abbot, were often interred in stone sarcophagi in the church. All of these extra buildings and areas were typically enclosed within the circuit wall of the abbey.

The End of the Abbeys

From the second half of the 14th century, many abbeys faced great challenges and even total disaster. The arrival of the Black Death in Europe and a series of famines eroded the wealth of the monasteries, while the collapse of medieval serfdom reorganised communities into a more independent existence. Finally, many rulers sought to seize the wealth and tax income from the monasteries, most infamously Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547), whose rapacious dissolution of the monasteries in Britain began in 1536. The golden days of the grand abbeys were over. A select few, like the abbeys and priories at Chester, Canterbury, Winchester, and Durham, to name a few, became cathedrals, but most former abbeys became picturesque yet oddly permanent ruins, their fine stonework plundered for reuse elsewhere. Still other abbeys, especially in Continental Europe, were converted over time into hotels, hospitals, schools, art galleries, and whatever else their new owners thought profitable as the importance of religion in people's lives declined.

Some abbeys vanished completely, with new manors and country houses built from their stones over the site, with only the old ecclesiastical name living on, such as 'The Abbey', 'The Priory', or 'The Grange' for these new secular properties. Despite the changing times, some abbeys do continue to fulfil a religious function, such as Westminster Abbey in London and many others dotted around Europe, perhaps most famously in Meteora with their dramatic cliff-top location that still provides a haven of retreat for those who wish to pursue a monastic life.