The state created by Diocletian and Constantine used to be described as despotic and oppressive, extracting higher taxes and threatening its subjects with punishments for non-compliance. Recent research, however, paints a different picture. The government strove to be responsive to the needs of its subjects, fair in the allocation of taxes, and to hold its official accountable for their misdeeds.

Government in the Eastern Roman Empire

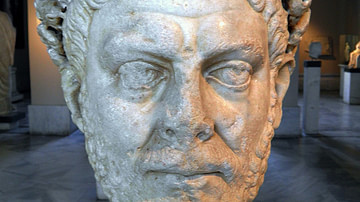

The government of the new empire has often been characterized as a totalitarian and theocratic dictatorship that suppressed the civic culture of the ancient world, eroded political freedom, and subordinated its subjects to a corrupt plutocracy and the intrigues of court eunuchs who encircled a quasi-divine monarch. Diocletian (r. 284-305) was allegedly the first to adopt a despotic style, adorning his robes and footwear with gems, requiring prostration, and being hailed as dominus, "lord." Constantine I (r. 306-337) extended the scope of capital punishment and threatened malefactors with the amputation of limbs or pouring molten lead down their throats. This image of oriental despotism was promoted by the thinkers of the Enlightenment, but its persuasive power has now waned. It was a rhetorical construct that served the needs of the 18th century, but it fails as a description of the reformed Roman government.

The new administration had to be more efficient at extracting revenue in order to pay for its own overhead – the salaries of new officials – as well as supply a large army. A hostile observer groused that there were more employees in Diocletian's government than there were taxpayers. While exaggerated, this complaint captured the unprecedented scale of the new empire's intrusion into

local society. Imperial bureaucracy on such a scale was massive by ancient standards. According to one estimate, the number of the central state's salaried officials rose from fewer than 1,000 to 35,000 or more. For a population of around 45 million, this is a low ratio by modern standards. Yet many of those officials were aided by attendants and slaves who did much of the actual work but did not show up on the books. The army and Church had their own managers, accountants, lawyers, and staff. Also, the imperial state was assisted locally by the apparatus of city governments, that is the city councilors and their agents and slaves. Finally, we should not use modern standards to assess how effective this bureaucracy was at surveilling and regimenting the population, as the latter was relatively immobile and economically undiversified compared to its modern counterparts.

Taxation

It is not clear that the tax burden rose much or at all. It was, however, more uniformly distributed and possibly more equitably too. The assessment, after all, was calculated on the basis of individual holdings: each iugum owed so much grain, wine, cash, etc. This curtailed the discretionary power of city councilors to allocate the tax burden. This equalization was intentional. Constantine declared in 324 that assessments on municipalities had to be based on the schedule published by the governor "so that the multitude of the lower classes may not be subjected to the arbitrariness and subordinated to the interests of the more powerful" (Theodosian Code 11.16.3-4.). This shifted power away from local authorities to surveyors and assessors appointed by the center.

Moreover, the bleak picture of an oppressed peasantry has been radically revised by archaeology. There is now mounting evidence for peasant prosperity in the 4th and 5th centuries. Settlements grew and acquired amenities that were previously limited to cities, and peasant households acquired goods that had previously been beyond reach. Some villages became 'urbanized.' Far from crushing small farmers, the new tax system may have spurred their economic productivity while shifting some of their prior tax burden to wealthier landowners, leading the latter to construct the familiar complaint of an oppressive state. It is more telling that there were no significant peasant rebellions in the history of the Eastern Empire. In periods when the East Roman state had its way in the provinces, we see steady economic and demographic expansion. The emperors, moreover, for all their bejeweled robes and lofty titles, worked hard to persuade their subjects that they were laboring tirelessly on their behalf.

New Imperial Policy

The imperial government itself, above and beyond the individual emperors, projected personality traits of its own. These included paternal solicitude for the welfare of all its subjects, even for 'the common happiness'; a striving for the rule of law and fairness in its dealings with them; and responsiveness to their concerns. The emperors certainly did work hard. There were many years when Diocletian, Constantine, and Constantius could, had they so chosen, idled in the pleasures of Rome rather than slogging through the mud of Danubian campaigns. And even while they marched along the frontiers, their courts and subordinates in the provinces were answering thousands of petitions from their subjects. The praise that emperors received doubled as a subtle reminder of their duties: "forget yourself and live for the people; observe which governors emulate your justice; receive messengers from every quarter; send out just as many dispatches; spend all your nights and days in perpetual concern for the safety of all" (Panegyrici Latini 10.3.3-4.)

In their official pronouncements, emperors strove to explain why taxes were necessary: without them, citizens could not be protected from barbarian attack: "the taxes paid by our subjects are used and expended for their own benefit" (Justin II, Novel 149.2). This was understood at every level of society, as far down the social ladder as our texts allow us to see. A lowbrow provincial saint's life about a dragon who had squatted in the imperial treasury in Constantinople explains how that cash cycle worked: "the taxes flow into the palace from all over the world and then the emperor uses the money to provide for the common needs of the republic" (Life of Hypatios of Gangra 8)

Provincial authors with even a modest grasp of history understood that the new empire was different from its predecessor: "what Rome once extorted from us at sword-point to satisfy her own extravagance, now she contributes with us for the good of the state we share" (Orosius, Seven Books of History against the Pagans 5.1.13.). And the violence threatened by the emperors, which has earned them a reputation for 'savagery,' was directed mostly against their own corrupt officials. In fact, our knowledge of the various crimes that officials committed comes from laws issued against them. Emperors armed their subjects against their own officials, and throughout East Rome's history, we have evidence that common people used these laws to seek redress.