The Native American concept of land ownership differs significantly from that of the European settlers who colonized the Americas or their descendants in that land could not be owned, only stewarded and lived with. The Earth is understood by Native Americans as a living, sentient being, and, therefore, no one can claim ownership.

To Native Americans, the Earth is one's relative, requiring respect and care, as are all the animals and plant life the land supports. The definition of one's 'relatives' encompasses all living things, not just the members of one's family, and so, just as one would not claim to 'own' a relative, one cannot own the land; one can only act as a steward in caring for it. The European settlers' understanding of the land was quite different as it was informed by the passage in the Bible from Genesis 1:28:

God blessed them and said to them, "Be fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground."

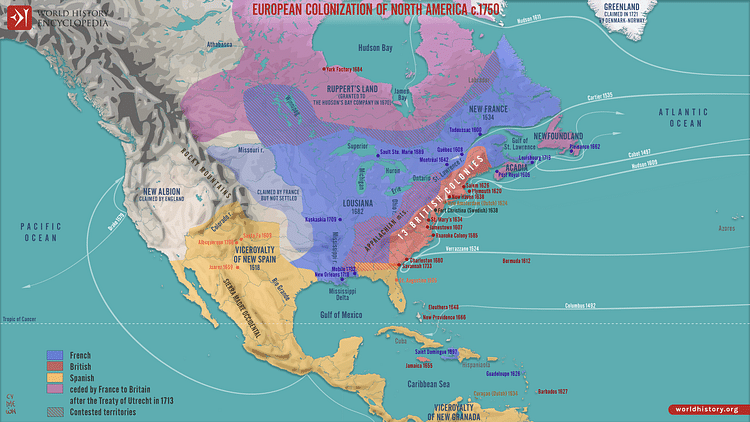

In the European view, the Earth and everything upon it essentially existed for the benefit of human beings, and so, of course, one could claim ownership of it in the course of subduing, taming, and reaping the benefits of that land. When the Europeans began interacting with the Native Americans, these differing views led to significant conflict, but the Europeans, operating in accordance with the concept expressed by the policy of the Doctrine of Discovery (established by the Catholic Church in 1493 to Christianize the natives of newly 'discovered' lands), claimed that non-Christians could not own land and felt free to take whatever lands were 'discovered' pursuant to the will of God as expressed in Genesis 1:28.

The Doctrine of Discovery (also known as the Discovery Doctrine) is addressed in its own article and will only be touched on briefly here, but its tenets came to inform the municipal law of the United States in 1823 through the ruling of Supreme Court Justice John Marshall in Johnson v. McIntosh, which established the policy claiming indigenous peoples had a "right of occupancy," but not of ownership of their land. This ruling was based on the Doctrine of Discovery, which held that any lands 'discovered' by a sovereign Christian nation became the property of that nation simply by virtue of their arrival in a region before any other and the planting of their flag.

The Native American understanding of land stewardship, however, rejected this claim, as well as the biblical injunction, and continues to in the present day. In their view, the Earth, as any living being, requires clean water and air, personal attention and love, and should not be claimed to be 'owned' by anyone to do with as they please but, rather, stewarded by those who recognize and respect its sentience. As stewards of the land, one does not subdue it or any of the creatures who live upon it but cares for the Earth as one would a family member.

Native American stories, of any nation, always touch upon the land in one way or another as an integral aspect of the narrative. The events in a story told by a member of a specific nation are understood to have happened on the same land where the audience sits listening to the tale. Stories such as the Origin of the Prairie Rose or Sun Dance Mountain, from the Sioux, both illustrate this traditional understanding in that they are origin tales concerning Sioux land and the connection between that land and the people.

Depriving the people of their land, therefore, undercuts their culture because the stories, rites, practices, and traditions are no longer observed on the land that gave birth to them but on foreign ground the indigenous people were relocated to in accordance with the European understanding of land ownership. This understanding – and the conflict between it and the Native American view – informs the modern Land Back Movement of indigenous peoples of North America who are demanding the return of their ancestral lands and the national sovereignty of each tribal nation to steward those lands as they did for thousands of years before the European colonization of the Americas.

Native Americans & the Land

The modern understanding of the origin of the Native Peoples of North America is that they migrated from Asia across the Bering Land Bridge (also known as Beringia), which linked the regions of modern-day Siberia with Alaska at some point around 40,000 BCE. These people are then said to have steadily spread out across and down the regions of modern-day Canada and the United States, perhaps at the same time as others were arriving by sea and settling along the west coast of the North American continent.

In this narrative, Native Americans came from somewhere else because some explanation is required as to how they came to be living on the land for thousands of years before they were encountered by Europeans. All Native American origin stories, however, claim the people came from the land they lived on. Details differ from nation to nation, but the underlying form of the tale is the same: a Higher Power created the world and made the people, plant life, and animals who lived in a specific and recognizable region. The land itself is understood in these stories to have given birth to the people and the plants and animals around them. The Earth, therefore, is recognized as one's mother and the plants and animals as one's brothers and sisters. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman comments:

Most Native American origin stories give people no more power than the other parts of creation; people are the Earth's partners and know it intimately as the source from which they sprang. The lands on which Indians live reflect the creation and there is a rich body of stories that detail how things came to be. The places where peoples are believed to have originated are always revered, and the accompanying tales typically intertwine the mythical with the real. Taken together, the stories constitute a canon of themes in which the complex relations between land, weather, plants, animals, and people are described. The land is filled with mystery and power – it has existed since the beginning of time and will last for as long as the people are there to tell the stories. (76)

The land keeps the people alive, and the people, recognizing this, respond with care for the land, and, through the stories told about it, remind each other and the next generation of the importance of this relationship. These stories are sometimes narratives of a great hunt or of a certain famous figure – as in the Sioux tale, The Brave Who Went on the Warpath Alone and Won the Name of the Lone Warrior – or perhaps touch on the afterlife as in A Teton Ghost Story – but, whatever the subject, the land is central to the narrative and as important as any other character in the tale. In some stories, though, the Earth features as the central character, and these serve to explain how the land came to look the way it does, giving the Earth a personal narrative that furthers its connection to the people.

Origin of the Prairie Rose

One famous example of this type of story is the Origin of the Prairie Rose, which explains how the wildflower known as Rosa arkansana came to be. The story personifies the prairie rose, the other flowers, the wind, and the Earth itself, reminding the audience that all of these are living things and, as such, are deserving of respect.

The following text, as well as the story of Sun Dance Mountain that follows it, are taken from Voices of the Winds: Native American Legends by Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark.

Long, long ago, when the world was young and people had not come out yet, no flowers bloomed on the prairie. Only grasses and dull greenish gray shrubs grew there, and it was the playground of the Wind Demon. Mother Earth felt very sad because her robe lacked brightness and beauty.

"I have many beautiful flowers in my heart," Mother Earth said to herself. "I wish they were on my robe. Blue flowers like the clear sky in fair weather, white flowers like the snow of winter, brilliant yellow ones like the sun at midday, pink ones like the dawn of a spring day – all these are in my heart. I am sad when I look on my dull robe, all gray and brown."

A sweet little pink flower heard Mother Earth's sad talking. "Do not be sad, Mother Earth, I will go upon your robe and beautify it."

So, the little pink flower came up from the heart of the Mother Earth to beautify the prairies.

But when the Wind Demon saw her, he growled, "I will not have that pretty flower on my playground."

He rushed at her, shouting and roaring, and blew out her life. But her spirit returned to the heart of Mother Earth.

When other flowers gained courage to go forth, one after another, Wind Demon killed them also - and their spirit returned to the heart of Mother Earth.

At last, Prairie Rose offered to go. "Yes, sweet child," said Mother Earth, "I will let you go. You are very lovely and your breath so fragrant that surely the Wind Demon will be charmed by you. Surely he will let you stay on the prairie."

So, Prairie Rose made the long journey up the dark ground and came out on the drab prairie. As she went, Mother Earth said in her heart. "Oh, I do hope that Wind Demon will let her live."

When Wind Demon saw her, he rushed toward her shouting, "She is pretty, but I will not allow her on my playground. I will blow out her life."

So he rushed on, roaring and drawing his breath in strong gusts. As he came closer, he caught the fragrance of Prairie Rose.

He said to himself, "Oh, how sweet! I do not have it in my heart to blow out the life of such a beautiful maiden with so sweet a breath. She must stay here with me. I must make my voice gentle, and I must sing sweet songs. I must not frighten her away with my awful noise."

So, Wind Demon changed. He became quiet. He sent breezes over the prairie grasses. He whispered and hummed little songs of gladness. He was no longer a demon.

The other flowers came up from the heart of the Mother Earth, up through the dark ground. They made her robe – the prairie – bright and joyous. Even Wind came to love the blossoms growing among the grasses of the prairie. And so the robe of Mother Earth became beautiful because of the loveliness, the sweetness, and the courage of the Prairie Rose.

Sometimes, Wind forgets his gentle songs and becomes loud and noisy, but his loudness does not last long. And he does not harm a person whose robe is the color of Prairie Rose.

Sun Dance Mountain

The story of Sun Dance Mountain is an origin tale of the Sun Dance, one of the seven sacred rites of the Sioux, observed by the indigenous peoples of Canada and the United States in the present day in, roughly, the same form as it was by their ancestors. The Sun Dance serves to awaken the Earth after winter, give thanks to the Great Spirit for the gifts of the Earth, and give back to the Creative Spirit in gratitude for all one has been given.

In this story, the origin of the dance is given as a celebration of the marriage of a young brave who endures hardships to win the blessing of the Sun God and a beautiful maiden who recognizes the value of love over material wealth. The couple represents courage, determination, commitment, and self-sacrifice, which are all cultural values of the Sioux nation as well as Native Americans in general.

Many, many years ago, a wise old warrior said to a beautiful maiden, "If you will marry a brave that is pleasing to the Sun God, you will bring good fortune to yourself and to all of our people."

The beautiful maiden had many wooers and knew many young men who had ponies and gold and who would like to marry her. But she really favored one who had nothing to offer her except his love. She promised him that, when he had the blessing of the sun, she would marry him.

So, the young brave started forth to seek the Sun and get his blessing. After many months of search and difficulties, he found the Sun God and received his blessing. He then returned to his beloved and they were married.

After the marriage ceremony, the people of the young brave held a dance at the foot of the mountain. Many different kinds of dances were performed, including the Sun Dance. The Sun Dancers danced all the day under the scorching sun. Some of them had no food and no water all day. Some pierced their ears so that they would bleed while they danced.

They made these sacrifices in order to obtain the favor of the Great Spirit Above. This dance, honoring the marriage of the beautiful maiden to the young brave who had been blessed by the Sun, became an annual affair. The dances that were held at the base of Sun Dance Mountain were revered by the Indians for a long, long time.

Conclusion

In both stories, the ancestral land of the Sioux features prominently – in the first, as the main character of Mother Earth and, in the second, as the site of the first Sun Dance from which all others have proceeded. Both origin stories serve to connect the people with the land that gave them life initially and continues to sustain them, and this is not only true of the tales of the Sioux but of all Native American nations who recognize their ancestral lands as their true home. Zimmerman writes:

This same powerful sense of rootedness in place can be found throughout the continent. The Cherokee use a word, eloheh, for land, which also means history, culture, and religion. It emphasizes how the people conceive of themselves as inseparable from their homeland. (79)

That sense of rootedness and the connection between the indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands is at the heart of the Land Back Movement in North America, which advocates for the return of indigenous peoples' lands. The movement is not promoting the relocation of large swaths of the Canadian or United States Non-Native population, but the return of the lands that were taken from them illegally through treaties that were never honored, were broken, and that used language which did not acknowledge the Native American understanding of the land or the difference between the European/American and the Native American concept of ownership.

The 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognizes that Natives of any country are entitled to their land, and the Discovery Doctrine has been condemned as racist and unjust – it was even repudiated by Pope Francis in March of 2023 – but, still, Native Americans continue to be deprived of their ancestral lands throughout North America. The Land Back Movement is only the most recent effort launched by Native American activists, as efforts to have their land rights recognized have been ongoing for over half a century or more, but a heightened awareness of the Native American struggle for justice is generating significant support for the Land Back initiative and, hopefully, the indigenous peoples of North America will soon be reunited with their homelands