The Battle of Waterloo (18 June 1815) was the last major engagement of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), fought by a French army under Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815) against two armies of the Seventh Coalition. Waterloo resulted in the end of both Napoleon's career and the First French Empire and is often considered one of history's most important battles.

On 1 March 1815, Napoleon returned from exile to regain control of his empire, beginning the period of the Hundred Days. The great powers of Europe responded immediately by branding him an outlaw and declaring war. The decisive Battle of Waterloo was fought between the towns of Mont-Saint-Jean and Waterloo in modern Belgium, then part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Napoleon's objective was to crush the Anglo-allied army of Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, before it could be reinforced by a nearby Prussian army under Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Napoleon nearly succeeded in his goal when his men captured the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte and stood poised to break through the allied center. However, the timely arrival of several Prussian corps and a failed charge by the French Imperial Guard dashed Napoleon's hopes of victory. Four days after his defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon abdicated for a second time and was exiled to the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where he would die six years later.

The Battle of Waterloo has often been regarded as one of the most decisive battles in history; it brought an end to the Napoleonic period and ushered in a new political era known as the Concert of Europe. Additionally, Waterloo marked an end to nearly 23 years of constant warfare that had devastated continental Europe since the Battle of Valmy in September 1792. After Waterloo, Europe enjoyed decades of relative peace, as the great powers did not fight another major war until the Crimean War (1853-1856). Still, the importance of the Battle of Waterloo is sometimes overstated; historians have argued that the odds against Napoleon were impossibly high, and had he not been defeated at Waterloo, he likely would have met his end on some other battlefield shortly thereafter.

Background

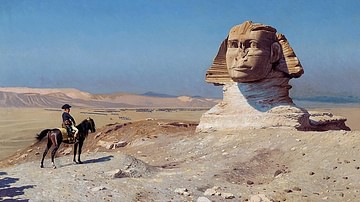

On 20 March 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte entered Paris and was practically carried to the Tuileries Palace by crowds of jubilant French citizens. Less than a year before, he had been forced to abdicate the French imperial throne after his defeat in the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814) and was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba. However, the ensuing Bourbon Restoration quickly led to discontent; several unpopular decisions made by the government of the new King Louis XVIII of France led many to fear for their liberties and think back fondly on Napoleon's regime. Hoping to exploit this unrest, Napoleon landed in southern France on 1 March; his progress to Paris was swift, as he was joined by thousands of defecting French soldiers. Louis XVIII barely had time to flee the capital when Napoleon entered it, beginning his second reign known as the Hundred Days.

After spending two decades fighting Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, the great powers of Europe were not about to let Napoleon upset the delicate balance of power in Europe again. On 25 March, they officially branded Napoleon an outlaw and formed the Seventh Coalition, which included the United Kingdom, Prussia, Russia, and Austria, as well as the newly formed United Kingdom of the Netherlands, and several German states. The Coalition planned to mobilize five armies against Napoleon. Two such armies would be sent to Belgium to threaten northeastern France – these included a 105,000-man Anglo-Dutch-German army under the British general Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, and a 120,000-man Prussian force under Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. A 200,000-man Austrian army would be positioned on the Upper Rhine, supported by 150,000 Russians on the Middle Rhine and 75,000 Austro-Italians further south. Once these armies were in place, they would make simultaneous drives toward Paris and Lyon, thereby constricting Napoleon's forces.

However, it would be a while before the Coalition armies could converge. By late May, only the armies of Wellington and Blücher were in position; it was estimated that the Austrians would not reach the Rhine until late July, with the Russians slated to arrive even later. This gave Napoleon an excellent chance to launch his own offensive before the other Coalition armies could materialize. Additionally, the Belgian population was largely sympathetic to Napoleon; a victory could trigger a pro-French revolution in Belgium. On 6 June 1815, the emperor began to quietly concentrate his new Army of the North for a surprise attack; in a little more than a week, he succeeded in moving more than 89,000 infantry, 22,000 cavalry, 11,000 gunners, and 366 engineers to the Belgian frontier from locations as distant as Paris, Lille, and Metz (Chandler, 1020). On 15 June, the Army of the North crossed the frontier at Charleroi, beginning the fateful Waterloo campaign.

Quatre Bras & Ligny

The Allies were not taken completely by surprise; several Prussian scouts had noticed a large concentration of campfires across the French border the night before. Suspicious, Blücher had concentrated his army at Ligny to await a potential French attack. Wellington, however, was taken more off guard. The duke had expected Napoleon to advance along the road from Mons to Brussels and had positioned his troops accordingly. But by advancing through Charleroi, Napoleon was actually moving in between Wellington's and Blücher's armies so he could keep them separated. Wellington did not learn of Napoleon's true intentions until the early morning of 16 June, when he was in Brussels attending the Duchess of Richmond's ball. When he was told that the French had occupied Charleroi, Wellington supposedly exclaimed, "Napoleon has humbugged me, by God!" (Mikaberidze, 608).

To keep the two Coalition armies separated, Napoleon had to capture the vital crossroads at Quatre Bras. He split his army into three parts: the left wing under Marshal Michel Ney would seize Quatre Bras while the right wing led by Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy and the reserve led by Napoleon himself would attack the Prussian army at Ligny. On 16 June, Marshal Ney arrived at Quatre Bras to find it lightly defended by 8,000 Dutch troops under the Prince of Orange; at 2 p.m., after a 14-gun bombardment, Ney ordered an assault. However, the Dutch enjoyed strong defensive positions and were able to hold the French off long enough for Wellington to pour reinforcements into the fray. By late afternoon, Wellington had 36,000 troops at Quatre Bras and had taken personal command; an Allied counterattack at 6 p.m. pushed Ney back and recaptured most of the ground that had been lost. The Battle of Quatre Bras ended in a draw, both sides having lost around 4,000 men.

The concurrent Battle of Ligny, however, was more intense. Spotting a chance to eliminate the Prussian army, Napoleon launched wave after wave of bloody assaults. Despite being outnumbered, the French put sufficient pressure on the Prussian line to break it by late afternoon; however, a series of miscommunications prevented the French from effectively harassing the Prussian retreat and crushing their army. Although Blücher himself was wounded and the Prussians lost over 17,000 casualties (compared to 11,000 French losses), they were able to make an orderly retreat to Wavre. Napoleon ended 16 June in a good position; he had badly mauled the Prussian army while Ney had cornered Wellington's force at Quatre Bras. All that remained was to finish what he had started the next day.

Interlude: 17 June

Napoleon, however, spent the morning of 17 June in an uncharacteristic state of lethargy. He slept late and wasted the crucial morning hours conducting troop inspections and touring the Ligny battlefield. It was only at 11:30 a.m. when Napoleon finally acted; Marshal Grouchy and 33,000 men were sent in pursuit of the Prussians while the emperor himself would link with Ney at Quatre Bras to deliver the killing blow to Wellington's army. Napoleon's lethargy has long been a subject of speculation; many historians have postulated that he was debilitated by an illness, with hemorrhoids or a bladder infection having been offered as candidates. Others believe that he was simply past his prime; in 1815, Napoleon was nearly 46 and overweight and perhaps had lost the energy on which he had built his career.

In any case, he did not link with Ney at Quatre Bras until around 1 p.m. By this point, Wellington had learned of Blücher's defeat at Ligny and had pulled back to the ridge at Mont-Saint-Jean, a few miles away from his headquarters at Waterloo. After receiving confirmation from Blücher that at least one Prussian corps would be able to aid him in the event of a battle, Wellington decided to hold this position. Napoleon's pursuit was hampered by the outbreak of a sudden thunderstorm; the sodden ground made it impossible for the French to pass through the countryside, and they were confined to using the roads which took considerably more time. By the time the French arrived opposite Wellington's army, darkness had fallen; the decisive battle would have to wait until the morning.

Preparations

By the dawn of 18 June 1815, the rain had stopped; only a valley of rain-soaked ground separated the French and Allied armies. Compared to other Napoleonic battlefields, the field of Waterloo is quite small; the battle zone consisted of only 4.5 kilometers (5,000 yards), stretching from the farmhouse of Hougoumont in the west to the village of Papelotte in the east. The French army, positioned on one ridge around the hamlet of La Belle Alliance, was 71,947 men strong. It was probably the best army Napoleon had commanded since the destruction of the Grande Armée in 1812; while the French armies of 1813-14 consisted of untrained conscripts, the Army of the North was made up largely of volunteers, veterans who were fiercely loyal to their emperor. However, for all its collective experience, the Army of the North had a brittle morale. Soldiers who had remained loyal to Napoleon throughout his exile mistrusted the soldiers who had sworn allegiance to the Bourbons and had since returned; in the words of one historian, "Napoleon had never before handled an instrument of war that was at once so formidable and so fragile" (Chandler, 1023).

Wellington's army was still drawn up on the Mont-Saint-Jean ridge. The Anglo-allied position resembled a wedge; the majority of Wellington's troops were deployed on his right flank while his left, east of the Brussels road, was lightly held. This was because Wellington was counting on the arrival of the Prussians to reinforce this flank. To slow the French advance, Wellington posted outlying troops at the forward positions of Papelotte, Frischermont, and La Haye Sainte. His army was truly a multinational one. It consisted of 24,000 British soldiers and 6,000 troops from the King's German Legion, as well as 17,000 Belgian and Dutch troops and 20,000 German soldiers from Hanover, Brunswick, and Nassau, a total of 67,000 men. Most of the British soldiers were veterans of the Peninsular War (1807-1814) and had served under Wellington before. Whether Wellington prevailed would depend on whether the Prussians could evade Grouchy at Wavre and march to Waterloo in time.

Battle Begins

Early in the morning, Napoleon held a breakfast conference with his senior officers at his headquarters in Le Caillou. Here, a report was made by Napoleon's brother, Prince Jerôme Bonaparte, about an overheard conversation between two British officers that strongly hinted that Blücher planned to come to Wellington's aid. Napoleon dismissed this report outright as mere gossip. Equally as fatefully, the emperor ignored warnings from his officers to not underestimate Wellington, whom Napoleon had never personally faced in battle before. The emperor responded by calling the duke "a bad general," the English soldiers "bad troops," and quipping that "this affair is nothing more serious than eating one's breakfast" (Mikaberidze, 610).

The battle began a little after 11 a.m., with the artillery of French General Reille's II Corps bombarding the Allied line. This was to be accompanied by an attack on the Allied position at the Hougoumont farmhouse, carried out by Prince Jerôme's division. This was only supposed to be a diversionary assault; however, the Hanover and Nassau troops defending Hougoumont proved more stubborn than expected. By 12:30 p.m. this 'diversion' had turned into a bloody struggle that would last the rest of the day and would keep Reille's corps pinned down. Although Wellington sent in reinforcements, the struggle there did not greatly affect his own overall disposition.

Meanwhile, Napoleon unleashed an 84-gun bombardment on the Allied line. The cannonade, however, inflicted only minimal damage; most of Wellington's troops were positioned safely behind the ridge while the soft, rain-soaked ground prevented the cannonballs from ricocheting. At 1:30 p.m., Napoleon sent forward the I Corps under Count d'Erlon to ascend the ridge and break the Allied line. D'Erlon's troops advanced in several lines 250 men wide, an awkward formation that proved both unwieldy and vulnerable; as the French moved through chest-high rye fields, they became easy targets for Wellington's artillery. Despite heavy losses, d'Erlon's battered divisions inched toward the Allied positions. One French division engaged a battalion of the King's German Legion at La Haye Sainte near the center of the Allied line, while additional French divisions captured Frischermont and Papelotte. Before long, d'Erlon's men had nearly crested the ridge.

At this point, Sir Thomas Picton's 4,000 British troops rushed forward to halt d'Erlon's assault; although Picton himself was killed, the British succeeded in pinning down d'Erlon's men. At this crucial moment, the Earl of Uxbridge – Wellington's second-in-command – ordered forth two brigades of heavy cavalry that had been hiding behind the ridge. These included the Scots Greys, who charged into action with shouts of "Scotland forever!" (Chandler, 1078). This surprised the French troops, who hurried to form a square; despite putting up fierce resistance, d'Erlon's entire corps was soon fleeing back down the ridge.

The Prussians Arrive

At around 1:30 p.m., three Prussian corps were approaching Napoleon's right flank. Blücher had managed to give Grouchy the slip by leaving one corps behind to pin him down at the concurrent Battle of Wavre, freeing up over 48,000 Prussians to march to Wellington's aid. Napoleon decided to keep focusing on the Anglo-allied army and hoped that Wellington would be crushed before the Prussians came close enough to intervene. After the failure of d'Erlon's charge, however, Napoleon was forced to divert additional units to his right flank to meet the Prussians; by 4 p.m., 7,000 French were holding back 30,000 Prussians between Frischermont and Plancenoit.

With the situation growing dire, Napoleon knew he had to break Wellington before more Prussians could arrive. At 3:30 p.m., he ordered Ney to capture La Haye Sainte, near the Allied center, at all costs; but Ney, who believed he had spotted a weakness in Wellington's center-right line decided it would be better to launch a massive cavalry charge. Yet as the French cavalry thundered toward the Anglo-allied line, it became slowed by the sodden ground, giving the Allies sufficient time to form squares; Wellington positioned field guns in between each square. Ney's charge broke upon the wall of British bayonets, as French horsemen were blown to bits by the field guns. Several more French cavalry charges were attempted but to no avail. Finally, Uxbridge's cavalry sallied forth to chase off the remaining French horsemen.

Charge of the Guard

At 6 p.m., Napoleon reiterated his orders to Ney to capture La Haye Sainte; this time, Ney led a coordinated attack that succeeded in capturing the farmhouse. The marshal wasted no time setting up a battery only 275 meters (300 yards) from Wellington's center, from whence he unleashed deadly fire onto the Allied line. This was the pivotal moment; Wellington's center was close to breaking while the Prussians were still being detained by the French at Placenoit. Napoleon knew that this was the time to break through the Allied center, but the only fresh French units were fourteen battalions of the dreaded Imperial Guard. At 7 p.m., Napoleon ordered them forward.

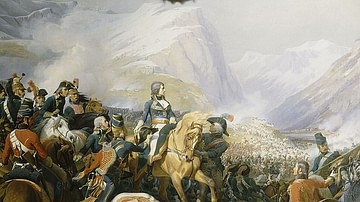

The Imperial Guard marched forward with great fanfare, close to 4,000 strong. Amidst the chaos of the battlefield, the charge eventually split into two separate columns, likely by mistake, allowing Wellington to focus on each in turn. Allied cannons and musket fire tore the Imperial Guard to pieces as it advanced up the ridge; when the charge lost momentum, Wellington ordered a general charge with fixed bayonets. Before long, a cry went up that had not been heard on a Napoleonic battlefield for 15 years: "La Garde recule!" ("The Guard is retreating!"). French morale disintegrated as the soldiers fled, cries of "treason!" and "every man for himself" filling the air (Chandler, 1089). At the same time, the Prussians finally broke through the French defenses at Placenoit.

The battle was over; Napoleon's empire was doomed. It had been a bloody affair, resulting in between 25-33,000 French casualties and 24,000 Allied losses. Four days after the battle, Napoleon abdicated for a final time and was sent into permanent exile on St. Helena, where he would die in 1821. Waterloo marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars and ushered in a new balance of power, the Concert of Europe, that would last for the next several decades.