Caesarea Maritima, an ancient metropolis in modern-day Israel, was a remarkable engineering accomplishment. Extending Rome's military and commercial presence in the eastern Mediterranean in the latter years of the 1st century BCE, Herod the Great (r. 37-4 BCE), as a client king, constructed a whole city complete with a temple, palaces, amphitheater, theater, paved streets, waterworks, and a colossal harbor.

The City's East/West Plan

Built on the ruins of a Phoenician village called Straton's Tower, the city of Caesarea Maritima and its harbor worked jointly to further Rome's economic and military presence in the region. With its sanctioned location between the harbor and the city, the temple would also be an integrated part of all activity. As the harbor was the place receiving and initiating the export of goods, and the city was the administrative center for political and economic activity, the temple – as it harbored the sacred images of Julius Caesar as a god and Juno as the patron goddess of Rome – symbolized the bestowal of blessings and protection on the harbor and city. As Kenneth Holum relates, "the sacrificial festivals held at the temple were themselves quintessential urban moments" (57). As Herod and his planners had the advantage of starting new, they would create the main east/west plan of the city around the temple, starting with the harbor west at the temple's foot, then with the adjacent construction of the city, east of the temple.

The Temple

The temple's importance to city activity was undoubtedly reflected not just by its location but also by its size. Josephus mentions, as it could be seen from "a great way off, its size was immense" (Antiquities, 15.9.6). Possibly towering close to 30 meters (100 ft) from its column bases to the top of its pediment, the temple at Caesarea was 29 by 46 meters (95 by 150 ft). To compare, the platform measurement of the Greek temple of Apollo at Corinth was 21 by 53 meters (70 by 175 ft), and the greatest temple in Rome, of Jupiter, was 53 by 62 meters (175 by 205 ft).

As the harbor, for hydrodynamic reasons, angled slightly north, the temple's plan diverged with it, around 30 degrees from the city's grid. In relation to this divergence, Ehud Netzer shows the temple, with a surrounding peripteral colonnade, to be set on an expansive platform of 100 by 90 meters (328 by 295 ft) with a curvilinear feature on its eastern side. This curve would have been a thoughtful innovation to soften the clash of angles, as the temple's orientation diverged from the city streets. Additionally, colonnaded wings ran directly north and south from the temple to stairs at the periphery of the platform that would have led down to street level.

The Harbor

That the temple was oriented with the harbor's angle of construction again reflects its intended importance to the port. For all those entering, this alignment would have provided a full-on view of the temple as it oversaw the activity of ships and goods moving in and out. As the temple joined the city and harbor, it made a convincing statement that happenings within its precinct secured the blessings of the gods.

The port itself was artificial, with no natural bay or promontory to build on. Using a combination of hydraulic concrete and huge stone blocks, some weighing up to 50 tons, Herod's harbor was built like a fortress at sea. Supporting a superstructure of curtain walls reaching over 9 meters (30 ft) and towers over 18 meters (60 ft), its breakwaters, laid out on a circular course, housed nearly 40 acres of water. In comparison, the medium-sized port, Leptis Magna, upgraded by Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) at the end of the second century CE, contained only 25 acres. The harbor, therefore, appears to have been built to receive mass goods.

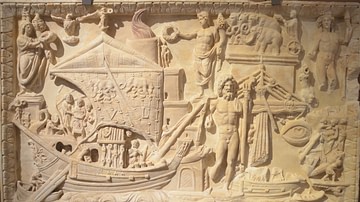

Ships of all sizes and types would have plied there, the largest being the Roman grain ships. The Isis, which sailed out of Alexandria, as described by Lucian, had a length of 55 meters (180 ft) with a beam width of 14 meters (45 ft). A merchant wreck, found in 1983, not far from the original harbor, dating to the late 1st century BCE or early 1st century CE, was 40 meters (132 ft) long and 12 meters (40 ft) in beam. However, the most common ships were the 100-to-300-ton merchant galleys with a length of 6-18 meters (20-60 ft) and a beam width between 3 and 6 meters (10-20 ft).

A lighthouse would have been the focal point for navigators, day or night. On entering the harbor, ships would furl their sails and would have relied on oars to navigate the entrance. Depending on the condition of wind and waves, a system of ropes and tugs may, at times, have aided vessels past the entrance. A harbor pilot would ensure ships were sent to their proper berths, tugged if needed, and adequately moored to the quay. Loading and offloading from the quays would involve laborers, carts, and cranes, with a harbor master overseeing all activity. He also would have been responsible for the all-important port fees and duty collection.

From Shore to City

Concerning traffic between the city and harbor, Josephus mentions streets leading from the city to the southern and northern breakwater arms: "Now there were continual edifices joined to the haven, which were also themselves of white stone, and to this haven did the narrow streets of the city lead and were built of equal distances one from the other" (Wars, 1.21.7). The "continual edifices joined to the haven" suggest an extension of the fortified wall system of the harbor to the city.

What is known of the original Herodian wall is that it encircled the city's original layout, terminating at the shore, north and south, distant from the harbor. Thus, for a complete encirclement of protection, the fortified wall system of the harbor would have angled ninety degrees north and south at the shore to meet the wider encompassing city wall.

Additionally, as the streets joining the harbor were thoroughfares expediting the transportation of goods, Josephus cites underground storage vaults located (like the streets) "at even distances to the haven," meaning, for loading purposes, at or near street intersections (Antiquities, 15.9.6) Beginning in 1971, such vaults in relation to the street grid have been found, which Robert Bull says "constitutes a huge warehouse complex and shipping installation." (35-36) Thus, as the harbor quays – laying inside their ramparts – merged with the city's streets with underground storage centers nearby, a seamless transport system was created between the city and harbor.

The City

Four streets ran north and south (cardines), and twelve decumani ran east and west. The east/west streets would have led to the harbor. The four thoroughfares that ran north and south would have been the arteries receiving goods from the region and would have intersected the narrower east/west streets to funnel traffic and goods to and from the harbor. However, setting the tone for those getting to their desired destinations was the main thoroughfare, the Cardo Maximus, one of the four north/south streets; 16 meters (54 ft) wide and almost 1.6 km (1 mi) long, it was bordered with mosaics and impressively lined with 700 columns, certainly of the ornate Corinthian type that also adorned the temple.

Scholars tend to place hypothetical public buildings and the agora nearby, east of the temple. Josephus also describes the splendor of the town, writing that the buildings were built with "white stone" and Herod "adorned [the city] with several splendid palaces." (Wars, 1.21.5-6; Antiquities 15.9.6). In Wars 1.21.8, Josephus also mentions a theater and amphitheater. The Roman theater, as it commands a view of the sea, is still used today. About 1 km south of the harbor, as it has undergone repairs over time, it accommodates an audience of about 4,000 people.

Then, in the city's northeast section, perhaps with wider popular appeal at the time and larger in size, was the amphitheater. As Caesarea was a center of sporting events in the Mediterranean world, Herod assigned the amphitheater to host games every five years, which likely included wrestling, boxing matches, and gymnastic events. Additionally, the hippodrome was one of the main structures in the city, dating to the 2nd century. More directly east of the harbor and home to one of the most popular ancient sports, chariot racing, it was gargantuan in size. Approximately 457 meters (1500 ft) long and 76 meters (250 ft) wide, it could seat 38,000 people.

Of the "splendid palaces" throughout the city, perhaps reflecting his own grandiosity, the largest and most splendid would have been Herod's. On an east/west rectangular plan, this magnificent structure was perched 457 meters (1500 ft) south of the harbor, on a lone promontory on the sea, thus the site's designation, Promontory Palace. At times, providing calm, expansive views of sunsets to the west, when the sea was tempestuous (which is often), enormous waves would have crashed loudly at the rocks below. Built with two adjacent levels, known as the upper and lower palaces, the lower 80 x 55 meter (260 x 180 ft) structure, closest to the sea, boasted a semicircular colonnaded porch that looked out onto the water. From there, walking back into the building, perimeter rooms would have accessed an inner colonnaded courtyard, the space which was largely filled with a 35 x 18 meter (115 x 60 ft) freshwater pool. In the middle of the pool stood a square pedestal for statuary. With a stairway leading up to it, the Upper Palace was dominated by a large 64 x 42 meter (210 x 138 ft) colonnaded courtyard.

The significance of this building as a capacious residence able to entertain many guests is reflected in the fact it became the headquarters for Rome's imperial activity in the area. Rome's long-term presence is evident with a recent find at the palace of "two column-shaped pedestals with inscriptions honoring four Roman procurators that date from the 2nd century to the early 4th century CE" (Burrel 57). However, Rome took early steps toward control. As Barbara Burrell et al. point out, in 6 CE Herod's palace "became the official residence of the Roman governor, and his kingdom became a Roman province, with Caesarea as its main port and administrative capital" (56).

Waterworks

As the Roman Empire used an extensive road system, Roman warfare employed superior long-term strategies and tactics by a professional army using superior war machines and standard personal equipment, but their success also relied on offering rank, wealth, and urban development to those they wanted to win over as allies. As Mary Beard says,

The foundation of towns from scratch, on a Roman model, was the most significant impact of Roman conquest on the provincial landscape. The provincial elites living in those towns acted as crucial middlemen between the Roman governor and the provincial population. In other words, pre-existing hierarchies were transformed into hierarchies that served Rome, as the power of local leaders was harnessed to the needs of the imperial ruler." (492-93)

In the case of Herod, as a client king of Rome, urban development played a critical role in advancing Rome's interests in the eastern Mediterranean. Essential to their plan for Caesarea, as with all of Rome's urbanizing efforts, was the provisioning of an adequate supply of water. If there is one singular feat for which Roman engineering is famous, it is the extensive use of aqueducts that accomplished the task.

The familiar above-ground aqueduct was a masonry-built structure of arches carrying a built-in channel of water set at the top. By being high off the ground, with an incremental descending grade, water could be carried from sources far away. Providing a plentiful supply of water, in addition to local sources, meant existing urban centers could experience greater urban growth, and locales that were once villages might themselves become urban. The aqueduct thus helped the empire to expand. And this is exactly what happened at Caesarea. One of the first things Herod and his city planners would have searched for was water sources to meet the future needs of the urban setting they were planning. In the case of Caesarea, several aqueducts were constructed at different periods, reflecting its own urban growth.

The first, so-called high-level aqueduct – 10 km (6.5 mi) long – found its water source in the Shumi Springs at the foot of the Carmel mountain range northeast of the city. However, excavators discovered that this aqueduct was, in fact, two joined structures carrying two channels of water. When a Latin inscription attributing its construction to Hadrian was found on the western face of the structure facing the sea, it was at first thought the dual aqueduct was built by Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE). Yet, when an Italian team in 1961 and Abraham Negev of the Israeli Department of Antiquities in 1964 discovered the western structure was only finished on the west side, while the eastern structure was finished on both sides, it was determined the western structure, built by Hadrian, was later joined to the original single aqueduct, likely built by Herod. Then, as the city grew and the demand for freshwater rose, another water source for the two channels was found approximately 16 km (10 mi) east of Caesarea. Tapping into that source, a 9.6 km (6 mi) rock-hewn tunnel, presumably constructed by Hadrian's engineers, conveyed water through limestone hills on a descending circuitous course until it reached the above-ground aqueduct, which carried both water sources the rest of the way to the city.

Further urban growth and demand are indicated by the discovery of a low-level aqueduct with its source in the Nahal Taninum River, 7 km (4.5 mi) north of the city. As Robert Bull points out,

This aqueduct, dated by pottery taken from beneath its concrete foundation, was in use in the fifth century. The volume of water carried in each of the aqueducts has been calculated and indicates that in the fifth century, the water demand of the growing city was about five times as much as it had been in the second century. (30)

Another important function of planned urban development was the conveyance of waste. Excavations at Caesarea discovered maintenance holes leading 3 meters (10 ft) down to a subterranean sewer system. One channel was found to be 3 meters wide and 3 meters deep. As Roman city planning called for sewers to be placed beneath city streets, reflecting the planned grid of the streets, Josephus describes "subterranean vaults, at even distances" leading toward the sea. He also describes this drain-field of lateral lines feeding into a main line that ran "obliquely" or diagonally. Likely of greater diameter to carry the collected volume of waste, the gravity-feed advantage of such a diagonally descending course carried the final effluent off, as Josephus says, "with ease." (Antiquities, 15.9.6) Josephus also mentions how tidal water from the sea somehow cleaned the drain system. While this cleansing could only have been of the lower portion of the drains, it is likely the whole system was fed additional water from the aqueducts. Finally, so the waste would be adequately carried away from the city, because of the strong currents moving north at this leg of the Mediterranean, the final effluent would have been located north of the harbor.

Conclusion

The time of Caesarea's construction represents the zenith and full extent of Rome's military and commercial presence to that point. With Europe, Anatolia, and Northwest Africa subdued, then with the conquest of Syria and Phoenicia, and finally Egypt, the Mediterranean Sea indeed became Mare Nostrum ("our lake") to the Romans. Yet Rome's military expansion and commercial enterprise did not stop there. The most lucrative northern east/west silk routes through Mesopotamia were controlled by Parthia: Rome's ablest competitor. Twice defeated in the latter half of the 1st century BCE, Rome sued for peace with the Parthian Empire in 20 BCE. However, in the meantime, with the long-term strategy of still winning Mesopotamia, Rome concentrated on solidifying control of the eastern Mediterranean region and securing the land and sea routes through Arabia and the Red Sea, which represented the eastern trade network of ancient Rome. Thus, as they played a crucial role in facilitating Rome's military and commercial interests in the region, Caesarea and its harbor represented Rome's engineering best.

Though just one of his many building projects, Herod built Caesarea with Rome's largess, not just on a grand scale, but with engineering finesse and innovation unrivaled until later medieval times. Then again, such grand-scale assembly of heavy stone materials into colossal yet finely adorned structures would create an expense difficult to fund in modern times. Hence, just for its infrastructure and buildings alone, the building of Caesarea and its harbor was indeed a remarkable engineering feat.