The Sioux who Married the Crow Chief's Daughter is a legend of the Lakota Sioux about Chief Big Eagle who left his people to marry a woman of the enemy Crow nation but never forgot the duties owed to his own people. The story highlights the values of personal honor and integrity.

It is also cited as an example of the practice of 'counting coup' and its importance in Native American warfare, of the value of horses in the tradition of the Plains Indians Culture, the challenges of inter-tribal marriages, and how members of different tribes who spoke different languages communicated with each other through signs.

The story is among the most popular of the Lakota Sioux and frequently anthologized as it is, at once, a love story, an adventure tale, and provides insight into the Plains Indians Culture.

Counting Coup

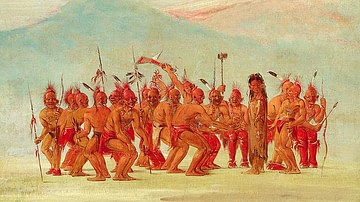

Historically, counting coup was a highly respected tradition of establishing one's reputation as a warrior for bravery and skill in battle. The warrior sought to touch an enemy, without killing him, either with the hand, a spear or lance, one's bow, a knife, or the object known as a coup stick – a wooden rod sometimes curved at the end. It was considered more honorable to disgrace an enemy warrior by counting coup on him than by killing him although the first 'coup' might then lead to his death in a second engagement.

The practice would be similar to tagging someone in a game. A warrior had to get close enough to the opponent to touch him and then get away before retaliation. A true 'coup' was struck when the warrior returned from its delivery unscathed. If one were successful, one could then place a notch in one's coup stick and/or place an eagle feather in one's headdress. One's opponent was understood to have been shamed and defeated by the coup and might leave the field of battle. If he refused to and was then killed by the same warrior who had counted coup on him, that was understood as a second coup, and if the dead man were then scalped, that constituted a third coup, just as then taking the man's horse became a fourth.

The greatest warriors – of the Sioux as well as other Plains Indians nations – were recognized by the number of notches on their coup sticks, feathers in a headdress, or other talismans indicating the number of opponents one had counted coup against successfully. Scholar Adele Nozedar comments:

The greatest honor was that initial touch, that contact with the living enemy. This was considered to be even more important than the killing. Considering this logically, it takes more nerve to have physical contact with a foe than it does to kill him from a distance, say, with a bow and arrow, or with a bullet from a gun. (117)

In the story, Big Eagle is respected by both his own people and the Crow nation he marries into for going into battle armed only with a coup stick. Although he participates in the war parties of the Crow against the Sioux, he refuses to kill his own people. In striking them with the coup stick, they become 'fallen' but have not been killed.

Summary & Themes

The plot of the story, on the surface, is simple. A Sioux warrior, Big Eagle, falls in love with a Crow woman who reminds him of his late wife, to whom he was devoted. He leaves his people to live with his new wife's family, but since the Crow and Sioux are enemies, he must honor his adopted family by fighting against his own people.

The central theme of the story is personal honor and recognition of one's responsibilities to one's people, whether those of one's birth or those one has been adopted by. After two years of living among the Crow, Big Eagle recognizes his duty to return to his own tribe to let them know what has happened to him and bring them gifts in the form of 220 horses.

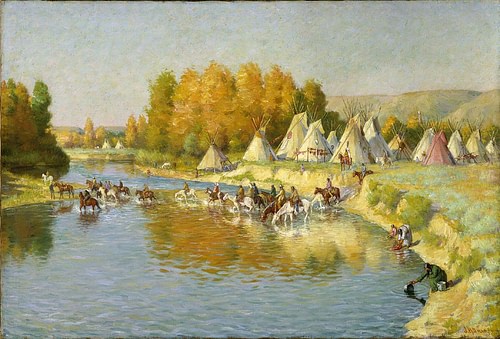

This detail in the story highlights the value of horses among the Plains Indians and how the horse was equated with wealth, prestige, and power. When Big Eagle returns with the horses, he is announcing his success, but in keeping with Native American values generally, he can only be counted a success if his accomplishments benefit the greater community as, in this case, with the horses being given to the needy people of his home village.

The story also touches upon intertribal communication. Prior to European colonization of the Americas, there were upwards of 500 different languages spoken by the Native Peoples of North America. To communicate with each other, they developed sign language, as in the early scene of the story where Big Eagle expresses his intentions to his future father-in-law. Big Eagle would have continued to rely on sign language until he had learned to speak and understand the language of his wife's people.

The story does not have a “happily ever after” ending in keeping with many, if not most, Native American tales, which reflect the reality of the people. The Sioux and the Crow do not become friends after Big Eagle marries the Crow chief's daughter nor after his final battle. The conclusion does not offer any hope of a lasting peace between the warring nations, only the lesson to be learned from the example of Big Eagle's life as an honorable warrior and chief.

Text

The following text is taken from Myths and Legends of the Sioux (1916) by Marie L. McLaughlin. It has been reprinted, however, in various anthologies of Native American legend and lore, including Native American Myths and Legends, edited by J. K. Jackson.

A war party of seven young men, seeing a lone tepee standing on the edge of a heavy belt of timber, stopped and waited for darkness, in order to send one of their scouts ahead to ascertain whether the camp which they had seen was the camp of friend or enemy.

When darkness had settled down on them, and they felt secure in not being detected, they chose one of their scouts to go on alone and find out what would be the best direction for them to advance upon the camp, should it prove to be an enemy.

Among the scouts was one who was noted for his bravery, and many were the brave acts he had performed. His name was Big Eagle. This man they selected to go to the lone camp and obtain the information for which they were waiting.

Big Eagle was told to look carefully over the ground and select the best direction from which they should make the attack. The other six would await his return. He started on his mission, being careful not to make any noise. He stealthily approached the camp. As he drew near to the tent he was surprised to note the absence of any dogs, as these animals are always kept by the Sioux to notify the owners by their barking of the approach of anyone. He crawled up to the tepee door, and peeping through a small aperture, he saw three persons sitting inside.

An elderly man and woman were sitting at the right of the fireplace, and a young woman at the seat of honor, opposite the door.

Big Eagle had been married and his wife had died five winters previous to the time of this episode. He had never thought of marrying again, but when he looked upon this young woman he thought he was looking upon the face of his dead wife. He removed his cartridge belts and knife, and placing them, along with his rifle, at the side of the tent, he at once boldly stepped inside the tepee, and going over to the man, extended his hand and shook first the mans hand, then the old womans, and lastly the young womans. Then he seated himself by the side of the girl, and thus they sat, no one speaking.

Finally, Big Eagle made signs to the man, explaining as well as possible by signs, that his wife had died long ago, and when he saw the girl she so strongly resembled his dead wife that he wished to marry her, and he would go back to the enemy's camp and live with them, if they would consent to the marriage of their daughter.

The old man seemed to understand, and Big Eagle again made signs to him that a party were lying in wait just a short distance from his camp. Noiselessly they brought in the horses, and taking down the tent, they at once moved off in the direction from whence they had come. The war party waited all night, and when the first rays of dawn disclosed to them the absence of the tepee, they at once concluded that Big Eagle had been discovered and killed, so they hurriedly started on their trail for home.

In the meantime, the hunting party, for this it was that Big Eagle had joined, made very good time in putting a good distance between themselves and the war party. All day they traveled, and when evening came, they ascended a high hill, looking down into the valley on the other side. There stretched for two miles, along the banks of a small stream, an immense camp. The old man made signs for Big Eagle to remain with the two women where he was, until he could go to the camp and prepare them to receive an enemy into their village.

The old man rode through the camp and drew up at the largest tepee in the village. Soon Big Eagle could see men gathering around the tepee. The crowd grew larger and larger, until the whole village had assembled at the large tepee. Finally, they dispersed, and catching their horses, mounted and advanced to the hill on which Big Eagle and the two women were waiting. They formed a circle around them and slowly they returned to the village, singing and riding in a circle around them.

When they arrived at the village they advanced to the large tepee and motioned Big Eagle to the seat of honor in the tepee. In the village was a man who understood and spoke the Sioux language. He was sent for, and through him the oath of allegiance to the Crow tribe was taken by Big Eagle. This done he was presented with the girl to wife, and also with many spotted ponies.

Big Eagle lived with his wife among her people for two years, and during this time he joined in four different battles between his own people (the Sioux) and the Crow people, to whom his wife belonged.

In no battle with his own people would he carry any weapons, only a long willow coup-stick, with which he struck the fallen Sioux.

At the expiration of two years, he concluded to pay a visit to his own tribe, and his father-in-law, being a chief of high standing, at once had it heralded through the village that his son-in-law would visit his own people, and for them to show their good will and respect for him by bringing ponies for his son-in-law to take back to his people.

Hearing this, the herds were all driven in and all-day long horses were brought to the tent of Big Eagle, and when he was ready to start on his homeward trip, twenty young men were elected to accompany him to within a safe distance of his village. The twenty young men drove the gift horses, amounting to two hundred and twenty head, to within one days journey of the village of Big Eagle, and fearing for their safety from his people, Big Eagle sent them back to their own village.

On his arrival at his home village, they received him as one returned from the dead, as they were sure he had been killed the night he had been sent to reconnoiter the lone camp. There was great feasting and dancing in honor of his return, and the horses were distributed among the needy ones of the village.

Remaining at his home village for a year, he one day made up his mind to return to his wife's people. A great many fancy robes, dresses, war bonnets, moccasins, and a great drove of horses were given him, and his wife, and he bade farewell to his people for good, saying, "I will never return to you again, as I have decided to live the remainder of my days with my wife's people."

On his arrival at the village of the Crows, he found his father-in-law at the point of death. A few days later the old man died, and Big Eagle was appointed to fill the vacancy of chief made by the death of his father-in-law.

Subsequently he took part in battles against his own people, and in the third battle was killed on the field. Tenderly the Crow warriors bore him back to their camp, and great was the mourning in the Crow village for the brave man who always went into battle unarmed, save only the willow wand which he carried.

Thus ended the career of one of the bravest of Sioux warriors who ever took the scalp of an enemy, and who for the love of his dead wife, gave up home, parents, and friends, to be killed on the field of battle by his own tribe.