The Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775) was a major engagement in the initial phase of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), fought primarily on Breed's Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The colonial troops successfully defended Breed's Hill against two British attacks, but ultimately retreated after a third assault. The battle was a British victory but cost them heavy casualties.

Prelude

By mid-June 1775, nearly two months had passed since the blood of colonial militiamen and British regular soldiers had been spilled on the Old Concord Road (modern-day Battle Road) connecting the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord. The intervening weeks had seen nearly 15,000 militiamen from across New England lay siege to the town of Boston, which was occupied by around 6,000 British soldiers commanded by General Thomas Gage. With the presence of British warships in Boston Harbor, the British garrison could keep itself supplied from the sea, while a lack of gunpowder and a poorly defined command structure prevented the colonial troops from mounting an assault on the town. This resulted in a standoff as the opposing armies – one comprised of untrained provincial farmers, the other considered the most disciplined fighting force in the world – waited for the other to make the first move.

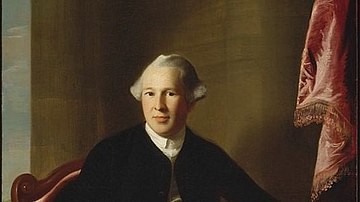

General Gage, by this point, was an unhappy man. A year earlier, he had been appointed military governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, entrusted with restoring royal authority in the wayward colony. But instead of reasserting British rule, Gage had allowed the colony to slip further from Parliament's grip and had consequently lost the confidence of King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820). Even before news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord had reached London, the king's ministry had dispatched a triumvirate of handpicked generals to assist the frustrated Gage in his duties; generals John Burgoyne, Henry Clinton, and William Howe had set sail for America aboard the vessel Cerberus, arriving in Boston on 25 May 1775. The generals, all of whom had well-established reputations in England, were appalled to find that soldiers of His Majesty's army were being besieged by country peasants and urged Gage to break out of this humiliating situation.

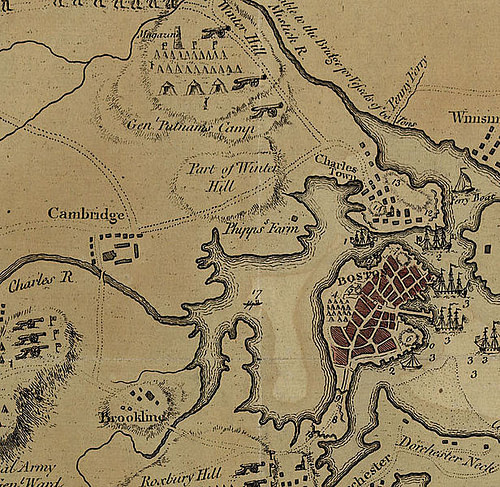

Boston, at the time, was confined entirely on a peninsula and was connected to the mainland by an isthmus known as Boston Neck. The colonial soldiers controlled access to Boston Neck, thereby cutting the British off by land, and were concentrated in the nearby towns of Roxbury and Cambridge. The British plan, mainly composed by General Howe, was to launch a surprise attack on Boston Neck and seize the strategically significant position of Dorchester Heights. After fortifying the heights, the British would sweep the Americans out of Roxbury before occupying Charlestown, located on another peninsula to the north of Boston. The British would then fortify the three hills overlooking Charlestown, which included Bunker Hill, Breed's Hill, and Moulton's Hill, before making the final push that would drive the provincials out of Cambridge. Howe suggested that the attack should take place on Sunday 18 June; the New Englanders, known for their piety, would likely be attending religious services and would have their guards down.

The British plan was, of course, made in secret, and was finalized on 12 June. However, the secret did not even last 24 hours before Howe's plan was delivered to the Provincial Congress, the acting American government of Massachusetts; the informant was an anonymous New Hampshire "gentleman of undoubted veracity" who had "frequent opportunity of conversing with the principal officers in General Gage's army" (Philbrick, 380). With five days to go until the British attack, the Provincial Congress decided to act preemptively, and instructed General Artemas Ward, commander of the ragtag New England army, to construct additional fortifications. On 15 June, General Ward elected to send a detachment of soldiers under General Israel Putnam to occupy the Charlestown peninsula; specifically, Putnam was ordered to seize and fortify Bunker Hill, which, at 33 meters (110 ft), was the tallest of the three hills on the peninsula.

Fortifying the Hill

At 6 p.m. on 16 June, approximately 1,000 colonial soldiers gathered in Cambridge opposite the headquarters of General Ward. They were commanded by 49-year-old Colonel William Prescott, the son of a distinguished Massachusetts family and a veteran of the French and Indian War. They were soon joined by a working party of 200 men from Putnam's regiment, led by Captain Thomas Knowlton, as well as by Colonel Richard Gridley, chief engineer of the provincial army who would oversee the construction of the fortifications on Bunker Hill. The colonial troops had no uniforms, wearing the same homespun civilian clothes that they had likely been wearing for weeks and carried muskets of all varieties. Each was given enough rations to last for a day and tools for digging trenches. At around 9 p.m., Colonel Prescott led the 1,200 men out of Cambridge and over Charlestown Neck.

Upon reaching Charlestown, Prescott was greeted by General Israel Putnam himself; at 57, Putnam was practically a mythological figure in the colonies, known for his exploits during the French and Indian War that included escaping capture by the Iroquois and surviving a shipwreck off the coast of Cuba. Putnam, Prescott, and Gridley held a meeting in which the decision was made to fortify Breed's Hill instead of Bunker Hill, as Ward had ordered. While it is unclear exactly why this decision was made, the most likely explanation was simply that the occupation of Breed's Hill would have been more provocative; standing 23 meters (75 ft) tall, Breed's Hill was closer to Boston, meaning the sight of an American fortification on it would necessitate a British response in a manner that a similar fort on Bunker Hill would not. Both Putnam and Prescott had long been itching for a fight and may have seen Breed's Hill as their ticket.

Gridley designed the necessary fortifications and, a little after midnight, the men got to work digging. The plan called for the construction of a square redoubt, about 40 meters (130 ft) on each side with ditches and earthen walls. The walls were 1.8 meters (6 ft) high and were affixed with a wooden platform for the men to stand on so that they could fire over the earthworks. Construction was still ongoing at 4 a.m. on 17 June, when dawn began to break over Boston Harbor; the provincials were spotted by a royal sloop, the Lively, which opened fire at them from the harbor. The Lively was unable to inflict much damage since it could not elevate its guns high enough to effectively fire on the hill, but it was soon joined by a British battery situated on Copp's Hill in Boston's North End.

Though the cannonade was mostly ineffective, it succeeded in terrifying the American troops, most of whom had never been under fire before. Prescott did his best to calm his men, assuring them that the British cannons were harmless at this range, but his assurances appeared hollow when a British cannonball tore the head off Asa Pollard, a soldier who had been digging in front of the redoubt. Pollard's gruesome death shook the last vestiges of courage from many of his comrades, as several provincial troops began to desert. Hoping to rally the men, Prescott leapt atop the redoubt's parapet, strutting back and forth and waving his tri-cornered hat as cannonballs zipped past his head. "Hit me if you can!" Prescott shouted to the British ships below, an inspiring performance that infused his men with enough courage to continue working on the hill. In Boston, meanwhile, General Gage was watching the excitement from a spyglass; noticing the eccentric man yelling from the parapet, Gage passed his spyglass off to an American Loyalist, Abijah Willard, and asked if he could identify the man. Willard replied that he could; it was his brother-in-law, William Prescott. "Will he fight?" Gage asked, to which Willard answered, "Yes, sir. He is an old soldier and will fight as long as a drop of blood remains in his veins" (Philbrick, 397).

The British Respond

The whistle and roar of artillery fire was heard from within the walls of Boston's Province House, where Gage was meeting with generals Burgoyne, Clinton, and Howe to discuss what was to be done. After some debate, it was decided that the British would land on the southeastern corner of the Charlestown peninsula near Moulton's Hill; this would allow them to threaten the left flank of the American redoubt, which was its most vulnerable point. General Howe would personally lead the major assault, which would attack the American left flank and, hopefully, swivel around to attack them in the rear. A simultaneous attack led by Howe's second-in-command, Brigadier General Sir Robert Pigot, would serve a diversionary purpose by launching a direct assault on the redoubt. The plan also called for a reserve force under Major John Pitcairn of the Royal Marines, who had recently won fame amongst the British officers for his leadership at Lexington and Concord.

It took six hours for the British to organize this force, which included a total of 1,500 men, and load them into 28 large barges. From the rooftops of Boston, civilians watched in awe as the British soldiers were rowed across the Mystic River; sitting motionless in their scarlet coats, their fixed bayonets glittering in the noontime sun, they must have looked like the very picture of British imperial retribution. The ships in the harbor intensified their bombardment to cover the soldiers' landing, which occurred close to 1 p.m. by Moulton's Hill. Their landing was uncontested by the Americans but, upon closer observation of the colonial position, Howe realized the attack might not go as smoothly as he had hoped.

The Americans had strengthened their left flank, which was now guarded by a fresh breastwork, called the rail fence, and was defended by Connecticut troops under Captain Knowlton. Even worse from Howe's perspective, the Americans had been reinforced by two New Hampshire regiments under colonels John Stark and James Reed. Among the American reinforcements was Dr. Joseph Warren, the popular young president of the Provincial Congress and perhaps the most important Patriot leader in Massachusetts at the time (Samuel Adams, John Adams, and John Hancock were in Philadelphia, attending the Second Continental Congress). Warren had been waiting for the arrival of his commission as a major general but, unwilling to be left out of the fighting, had chosen to temporarily serve as an infantry private. Finally, General Putnam had begun to oversee the construction of fortifications on Bunker Hill to compliment Prescott's position on Breed's Hill. Faced with this new situation, Howe decided to wait by Moulton's Hill and wrote to Gage requesting reinforcements. By the time these men arrived, it was 3 p.m.; although Howe now commanded a force of 2,400 men (against roughly 3,000 provincials), the Americans were better prepared now than they would have been had Howe attacked when he initially landed.

The Battle Begins

Howe's troops began forming into lines for their assault on Breed's Hill; General Burgoyne, watching from atop Copp's Hill, described this deployment as "exceedingly soldierlike. In my opinion, it was perfect" (Philbrick, 423). But while General Pigot's men were forming up just south of Charlestown, they came under fire from colonial sharpshooters, who were sniping from within the town. Howe appealed to Admiral Samuel Graves for help clearing the rebels out, leading Graves to fire two carcass shots into Charlestown. The carcass shots, described by author Nathaniel Philbrick as "circular metal baskets full of gunpowder, saltpeter, and tallow" exploded, and before long hundreds of Charlestown's wooden buildings were engulfed in flames (423).

Against this hellish backdrop, the British soldiers began their advance. The artillery that Howe had posted atop Moulton's Hill for covering fire was practically useless, once the artillerymen discovered they had brought the wrong size ammunition. Additionally, the hay on the side of Breed's Hill had not yet been harvested, forcing the soldiers to march through waist-high grass; troops were constantly tripping over rocks, holes, and fences concealed by the brush.

As Howe's men moved against the American left, and Pigot led the diversionary attack against the redoubt, several companies of British light infantry moved along a narrow beach that ran along the Mystic River. The beach was at the bottom of a bluff, atop which was the rail fence being held by Captain Knowlton; if the redcoats could circumvent Knowlton and the rail fence by way of the beach, they could flank the American position. But the light infantrymen, led by the famed Royal Welch Fusiliers, soon came across Colonel John Stark's New Hampshire regiment, waiting behind a hastily thrown together stone wall.

The narrowness of the beach had forced the light infantrymen into packed columns, making easy targets when Colonel Stark ordered his men to fire; Stark waited until the British were 50 paces away, and the American volley was devastating. Those unfortunate enough to be at the front of the British ranks crumpled to the ground, while the British officers urged their men forward, despite fresh hails of provincial bullets. After several minutes, the fusiliers withdrew, leaving 96 of their comrades lying dead on the beach; the dead, Stark would recall, "lay as thick as sheep in a fold" (Middlekauff, 296).

On the high ground to the west, General Howe's grenadiers were continuing their slow advance toward the rail fence, where Captain Knowlton's men lay in wait. Here, too, the provincials waited for the British to come close before unleashing a deadly volley. The smoke, as well as the difficult terrain, caused much confusion in the British ranks, stopping the advance dead in its tracks; the grenadiers, stumbling around in their attempts to reorient themselves, made easy marks for the Americans. The British officers, in their resplendent scarlet coats, especially stood out and were purposefully targeted. Before long, Howe's assault had disintegrated, and his men were making their way back down the hill face.

Howe rallied his men and tried again, but this assault ended as disastrously as the first; one American reported that the grenadiers resorted to piling up the bodies of their fallen comrades to take cover behind. Within 30 minutes, the grenadiers were once again in retreat. Pigot's attack on the redoubt, which had gotten off to a late start, did not fare much better. Worried about running out of gunpowder prematurely, Colonel Prescott ensured that his men did not fire until the regulars were almost on top of them; when the volley did come, Pigot's redcoats broke almost immediately. On all three fronts, the British assaults had failed.

The British Take the Hill

General Howe was shaken by the experience. His aide-de-camp had been killed at his side, and the sight of the dead and dying redcoats lying in the grass produced in him a "moment I have never felt before" (Middlekauff, 296). Still, Howe was not about to give up. He changed course, abandoning the rail fence and deciding to concentrate all his strength against the redoubt itself. Additionally, his troops were ordered to get rid of their packs so they could travel lighter and were ordered to march in columns rather than lines. Before long, Howe himself was leading the British column up the hill; his men, rather than feeling defeated, were eager to get revenge on the provincials and cried to "push on, push on!" (Middlekauff, 297).

Like before, Prescott's men waited until the last possible moment before unleashing their lead volley. The Royal Marines took the brunt of the damage with Major Pitcairn among the dead. While the marines wavered, the grenadiers pushed on, and with a roar, they jumped into the redoubt. This caused panic amongst Prescott's men, who began to run for their lives. At least 30 men became trapped in the redoubt and were bayoneted to death by the grenadiers. Dr. Joseph Warren, among the last to leave the redoubt, was killed by a shot to the face, after which his body was bayoneted by vengeful British soldiers to the point of near unrecognizability. Warren's death was a considerable blow to the Patriot cause.

With the fall of the provincial redoubt, the Battle of Bunker Hill (or Breed's Hill, as it perhaps should be known) was over. The colonists had initially retreated to General Putnam's position on Bunker Hill but, by 5 p.m., had evacuated back across the Charlestown Neck to take up positions in Cambridge. The Americans had lost 115 dead and 305 wounded, with most of these casualties coming during the frantic retreat. But the British, despite having won a tactical victory, suffered egregious losses; 226 British soldiers were killed and 808 wounded, leaving the total British casualty number at 1,054, or almost half of their entire force. A large portion of the British losses had been officers. For the British, it was the bloodiest single day of the entire war.

Aftermath

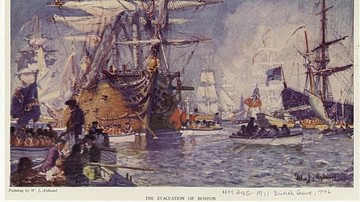

On 2 July 1775, only a few weeks after the battle, George Washington arrived in Cambridge to take command of the ragtag American force, soon to be reorganized as the Continental Army. The Siege of Boston would continue until March 1776, when the British evacuated the town. Despite the loss, the Americans were able to look to Bunker Hill as proof that they could effectively fight the British regulars. At the same time, the battle hardened the hearts of the British against the Americans and may have contributed to King George III's decision to reject the colonists' Olive Branch Petition, their last attempt at reconciliation before the American Declaration of Independence.