The Siege of Boston (19 April 1775 to 17 March 1776) was the first major military operation of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). After the first shots were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, American colonial militias laid siege to Boston, Massachusetts, which had become a stronghold for Loyalists and British troops.

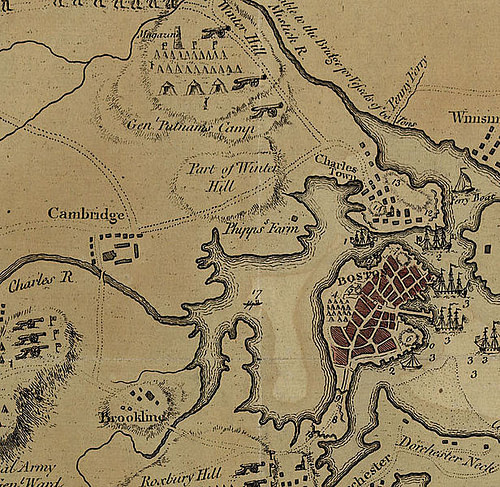

As news of Lexington and Concord spread, as many as 15,000 colonial militiamen made their way to Boston to participate in the siege; most of these men initially came from the New England colonies, though companies of soldiers from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia added their strength to the colonial army as the siege wore on. At the time, the town of Boston was confined entirely to a peninsula, and the Americans were able to cut the British off from the countryside by seizing Boston Neck, a narrow isthmus that connected the town to the mainland. However, the British controlled Boston Harbor, allowing them to resupply and reinforce by sea. Since the Americans lacked gunpowder, they could not assault Boston directly, leading to a months-long stalemate that was intermittently broken by events like the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775), the only major battle to take place during the siege.

On 2 July 1775, a Virginian planter named George Washington (1732-1799) arrived to take command of the American army at the behest of the Second Continental Congress. Despite his private concerns about the Americans' chances of victory, Washington whipped the ragtag army into decent shape, reorganizing it as the Continental Army. In February 1776, Colonel Henry Knox arrived with cannons taken from the recently captured Fort Ticonderoga. Washington positioned these cannons on the strategically significant Dorchester Heights, leaving the British with no choice but to either attack or evacuate Boston. British General William Howe opted to evacuate, and the last British ships sailed from Boston Harbor on 17 March 1776, the anniversary of which is still celebrated in Boston as 'Evacuation Day'. The end of the siege also marked the end of major military activity in New England, as the war spread to other parts of the Thirteen Colonies.

Beginnings

Since the first major cracks in the relationship between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies appeared in 1764, the colonial town of Boston, Massachusetts, was often found at the forefront of the dissent. It was in Boston where colonial agitators like Samuel Adams had first taken up the battle cry of 'no taxation without representation', it was in Boston where a mob of colonists had attacked the homes of royal officials in protest of the Stamp Act, and it was in Boston where British soldiers had first spilled American blood during the Boston Massacre. In December 1773, when the residents of Boston once again defied Parliament's authority by dumping 342 creates of British East India Company tea into the harbor, Parliament decided that the rebellious Province of Massachusetts Bay would have to be punished, lest British authority in America disappear forever.

In 1774, Parliament passed a series of policies known in America as the 'Intolerable Acts', which included the closure of Boston Harbor to all commerce until the East India Company was fully compensated by the town's residents for the damages incurred during the Boston Tea Party. Since the harbor was the lifeblood of the town, this was egregious enough, but Parliament went a step further by installing General Thomas Gage as Massachusetts' military governor and by replacing several of the colony's elected officials with royal appointees. In response to this perceived act of tyranny, the local militias from several Massachusetts towns began preparing for a potential conflict with British troops, while in October 1774, a group of Massachusetts political leaders formed the Provincial Congress in the town of Concord to act as a sort of provisional government to counterbalance the military government of General Gage.

Gage noticed the rising tensions in the colony and knew he did not have enough troops to crush the rebellion that was clearly coming. To postpone a conflict for as long as possible, Gage decided to confiscate stores of gunpowder and other military supplies that were stashed throughout the countryside in order to prevent them from falling into the hands of the colonial militias. In the early morning hours of 19 April 1775, he dispatched an expedition of 700 soldiers under the command of Colonel Francis Smith to raid the powder magazine in Concord. Despite the discretion with which Colonel Smith's men marched, their intentions had long been known to the Patriots; before the British had even set out from Cambridge, Patriot leader Dr. Joseph Warren had dispatched two riders, Paul Revere and William Dawes, on the road to Concord to alert the militias. Therefore, when Smith's troops approached the town of Lexington at around 4:30 a.m., they were confronted by some 70 militiamen. During the standoff, a shot rang out, prompting the British to fire two volleys at the militia, killing eight colonists and wounding another ten.

The British troops proceeded to Concord, where they were frustrated to find that the Americans had hidden most of the military supplies. By this point, news of the bloodshed at Lexington had spread, and as many as 400 colonial militiamen had gathered atop a nearby hill. Under the false assumption that the British were trying to set Concord afire, the militiamen descended the hill and began provoking the British troops stationed near Concord's North Bridge. The British opened fire, killing two Americans and wounding a third; the Americans unleashed an answering volley, killing three British soldiers and wounding nine. The shocked British troops then began a retreat to Boston, and were harassed by growing numbers of colonial militiamen along the way; by the time the British reached the safety of Boston at sunset, they had lost 273 casualties while the colonists suffered 95 losses. The Battles of Lexington and Concord kicked off the American Revolutionary War, and, as 15,000 American troops surrounded Boston, initiated the siege as well.

Initial Stages: April-June 1775

On 20 April 1775, the day after Lexington and Concord, General Artemas Ward took command of the provincial forces, which was comprised mostly of untrained militia from the colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. The colonial forces were concentrated in the towns of Roxbury and Cambridge, while the roughly 6,000 British soldiers were confined to Boston itself; at the time, Boston was a peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow strip of land called Boston Neck. The provincials controlled access to the Neck, cutting the British off by land, but the presence of British warships in Boston Harbor allowed the British to resupply themselves by sea. Although many Americans were itching for a fight, any thoughts of assaulting Boston outright were dismissed, owing to a lack of gunpowder.

Despite a regular stream of supply ships, Boston soon suffered from a food shortage, as the colonial troops denied the town access to livestock and fresh produce. Food prices in Boston sharply rose, and the rations of soldiers were reduced. Hoping to lessen these difficulties, General Gage reached an agreement with the colonial army to allow any Bostonian to leave the town who wished to do so, on the condition that they surrender their arms to the British. But at the last moment, Gage reneged on this promise; the town's Loyalists convinced him that, by freeing the town's Patriots who essentially served as hostages, the colonial army would have no reason not to attack Boston and burn it to the ground with the Loyalists and soldiers inside. With this breakdown in negotiations, the rate of skirmishes increased; on 27 May, in one notable incident known as the Battle of Chelsea Creek, the colonists seized and burned the British schooner Diana.

On 25 May, a ship arrived in Boston Harbor carrying a triumvirate of generals who had been handpicked by the king's ministry to assist Gage in his duties; John Burgoyne, Henry Clinton, and William Howe all enjoyed esteemed reputations in London and were expected to bring a quick end to this humiliating siege. Their plan was to seize the strategically significant ground of Dorchester Heights, from which they could sweep the colonists from their positions and end the siege. The attack was to take place on Sunday 18 June, when the notoriously devout New Englanders would be attending religious services. This plan, however, fell into American hands. Hoping to strengthen their own position, 1,200 colonists under General Israel Putnam and Colonel William Prescott were dispatched to the Charlestown peninsula, just north of Boston, to fortify Bunker Hill on the night of 16 June.

Putnam and Prescott disregarded these orders and occupied a more provocative position on Breed's Hill, closer to Boston; when dawn's first light on 17 June revealed that the colonists were constructing a redoubt on this position, the British decided that they could not be ignored. After an artillery bombardment reduced the wooden buildings of Charlestown to rubble, 2,400 British troops advanced up Breed's Hill, personally led by General William Howe. The Americans were well-entrenched and waited to fire until the British were practically on top of them, resulting in devastating casualties for the redcoats. Two British assaults were repelled before Howe's troops finally stormed the redoubt, chasing off the colonial troops and bayoneting those who did not run fast enough. Although the Battle of Bunker Hill was a British victory, they paid dearly for the success, suffering 1,054 casualties, including a disproportionate number of officers. The colonists lost around 400 killed and wounded including Dr. Joseph Warren, whose death was a considerable blow to the Patriot cause.

Washington Takes Command: July-October 1775

Although they had been defeated, colonial morale was high in the aftermath of Bunker Hill, as they had held their ground for a great length of time and inflicted more damage than they had received. The British, meanwhile, did not feel like victors; in the days after the battle, a cloud of death hung over Boston as soldiers died of their wounds and civilians succumbed to malnutrition. Normally, the town's church bells rang during a funeral, but Gage suspended this practice, as there were too many funerals. Around this time, the colonial army was suffering from an outbreak of typhus that was soon carrying off two or three men a day. Although the siege had settled into a stalemate, both armies were plagued by death.

It was also around this time that both armies experienced a change of command. General Gage's conduct had long met with the displeasure of the king's ministry, and he was finally recalled to England, with the defense of Boston now entrusted to General Howe. Meanwhile, George Washington arrived in Cambridge on 2 July, after having been dispatched by the Second Continental Congress to turn the ragtag New England force into a proper American army. Washington, a Virginian planter who had served closely with the British army during the French and Indian War, was disgusted by the state of the provincial army. The colonial militias elected their own officers, whose orders they often disregarded, and were prone to brawls to relieve boredom. Militiamen on sentry duty sometimes fraternized with the British while others swam naked in the Charles River. The camps were filthy, latrines improperly spaced, and furloughs were granted easily, with men constantly coming and going as they pleased. Washington could scarcely believe that these were the same men who had stood up to British regulars on Breed's Hill.

So, in the months following his arrival, Washington set about transforming the colonial army. He informed the men that they were now under the authority of the Continental Congress and that much would be expected from them since they were fighting for their countrymen's liberties. Strict discipline was enforced, as Washington forbade his men from drunkenness, wasting gunpowder, and talking with the enemy; court-martials were implemented, with offenders fined or even flogged. The bloated officer corps was reduced; since the army still lacked proper uniforms, Washington ordered his officers to wear different color sashes to denote their ranks. Just as Washington improved the discipline of his new army so, too, did he seek to improve the American fortifications. He ordered his men to dig trenches on Boston Neck, extending the American line closer to Boston.

This resulted in some light skirmishing. On 2 August, an American rifleman was killed by the British, who hung his corpse in full view of the colonial troops on Boston Neck; colonial sharpshooters responded by sniping at the British, killing several of them. On 30 August, the British ventured beyond the Neck to burn a tavern before safely withdrawing back to their defenses while, the same night, the Americans attacked Lighthouse Island, killed several enemy troops, and took 23 prisoners at the cost of only one American killed. In early September, Washington suggested that the time was right for an attack on Boston, but his officers unanimously disapproved of the plan, due to the lack of gunpowder. In October, Washington once again proposed an attack but was once again rebuffed. Both times, Washington yielded to their decision, although he was anxious to force a battle soon; the enlistments of many of his troops would expire in December and January, and he was unsure how many of them would re-enlist.

The Siege Ends: November 1775-March 1776

One thing that Washington and his subordinates did agree on was that the siege would never be won without proper artillery. Fortunately for the Patriots, there were cannons available at Fort Ticonderoga, which had been seized by colonial troops a few months earlier; the problem, however, was that Fort Ticonderoga was located at the southern end of Lake Champlain, hundreds of miles from Boston. Still, the artillery was sorely needed, and in November 1775, Washington dispatched 25-year-old Colonel Henry Knox to retrieve the artillery.

This resulted in one of the greatest feats of perseverance of the entire war. Knox and his team were faced with the daunting task of transporting 44 guns, 14 mortars, and a howitzer across difficult terrain with almost no quality roads. After arriving in Ticonderoga on 5 December, Knox loaded the artillery into flat-bottomed scows and sailed across Lake George. Then, the cannons were loaded onto 42 sleds to be pulled through the snow-covered fields of New York; Knox's team crossed the frozen Hudson River several times before finally arriving in Albany. After pulling a cannon out of the river where it had fallen through the ice, Knox attached the guns to a team of oxen to travel over the Berkshires. By late January 1776, he had reached the town of Framingham, Massachusetts, and, by February, the guns had been presented to General Washington in Cambridge.

By now, the army had been whipped into a decent shape; companies of riflemen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia had arrived to supplement the New England militiamen and join what was now being referred to as the Continental Army. With the addition of the cannons, Washington once again requested an assault on Boston. His officers were once again hesitant, recommending instead that the Americans occupy the strategic ground of Dorchester Heights; although the British had intended to occupy them before Bunker Hill, the heights had remained unoccupied for the duration of the siege up until this point. If the Americans could position artillery atop the heights, the British would be forced to either attack or evacuate Boston altogether. Washington approved this plan, and, by 4 March 1776, the Americans had fortified the Dorchester Heights. The ground had been too frozen to dig trenches, so the Americans had constructed fortifications out of timbers and fascines known as chandeliers.

As Washington's officers had predicted, the American position on Dorchester Heights forced the hand of General Howe; if ignored, the Americans could now bombard both Boston and the British ships in Boston Harbor with impunity. Initially, Howe felt that he had no choice but to assault the Dorchester Heights, for the honor of the army, but, as had happened in the American camp, Howe's officers advised him against it – a decision that Howe, still burdened by the bloody memory of Bunker Hill, did not need much persuading to accept. Howe was saved from any embarrassment by a sudden storm on 5 March that would have made it impossible to attack even if he wanted to. The only option left, then, was to evacuate.

Evacuation: 8-17 March 1776

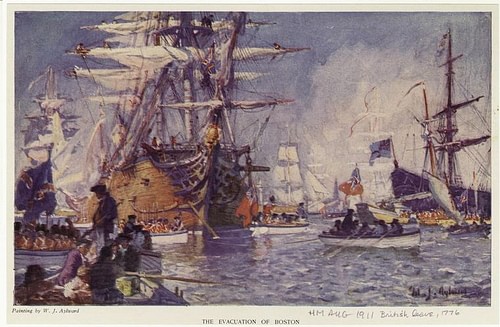

On 8 March, Washington received a letter from several of Boston's most prominent Loyalists, promising that the British soldiers would not burn Boston if the Americans allowed them to evacuate in peace. Although Washington formally rejected the letter, he nevertheless restrained his troops from firing on the British, allowing the soldiers to prepare for evacuation without hindrance. The frustrated British troops became prone to looting Boston houses during this time; Howe's threats to shoot any looter caught in the act had little effect on the plundering. The soldiers and several Loyalist families boarded the British ships and, when the wind turned favorable on 17 March, they sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia. After more than ten months, the Siege of Boston was over.

The Continental Army entered Boston over the course of the next few days but did not stay for long; concerned that the British planned to attack New York, Washington led his troops toward Manhattan on 4 April. Yet the first major operation of the Revolutionary War had ended in an American victory. From then on, New England escaped much of the ravages of the war, which continued to rage elsewhere in the colonies for the next seven years.