The Olive Branch Petition was a letter adopted by the Second Continental Congress on 5 July 1775 and sent to King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) in a final attempt at reconciliation in the early months of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The king refused to receive the petition and the colonies declared independence a year later.

At the time the petition was written, the war was quickly escalating, and many delegates of the Continental Congress believed that further bloodshed was inevitable; even as a committee began to draft the Olive Branch Petition, the rest of Congress was busy organizing the Continental Army and authorizing an invasion of British-controlled Canada. Yet the delegates also saw the value in making one final effort to achieve peace; if the king would not listen, it would at least prove to the world that the Americans were doing everything possible to avoid war and were not the aggressors.

The petition was penned primarily by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, was ratified by the Congress on 5 July 1775, and was sent to London three days later. It essentially blamed the situation on the tyranny of Parliament and the treachery of the king's ministers, and implored George III to intervene and return things to the status quo; the petition claimed that all the Americans wished was for harmonious relations between king and colonies to be restored. However, by the time the petition reached London, the king had already issued a Proclamation of Rebellion, which called for a suppression of the colonial rebellion, and refused to even receive the Olive Branch Petition. The Congress would make no further attempts to reconcile with the king and would instead adopt the United States Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776.

Context

The quarrel between Great Britain and its thirteen North American colonies had begun in 1764 when Parliament attempted to raise tax revenue by implementing the Sugar Act, which taxed the molasses trade in the colonies. This was followed by further taxes including the Stamp Act (1765) and the Townshend Acts (1767-1768), both of which caused mass outrage throughout the colonies. The Americans argued that their rights, enshrined in both the British constitution and in their own colonial charters, entitled them to self-taxation; since the Americans were unrepresented in Parliament, therefore, any attempt by Parliament to tax them violated their rights. Tensions escalated as Britain sent soldiers to restore order in the colonies and as royal governors suspended colonial legislatures. Events such as the Boston Massacre (1770), Boston Tea Party (1773), and the passage of the punitive Intolerable Acts (1774) by Parliament set the colonies on the road to war.

In October 1774, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to discuss a coordinated response to the Intolerable Acts. While there, the delegates drafted a Petition to the King, in which they listed their grievances and implored King George III to intervene on their behalf. At the time, many colonists still believed that the king was a benevolent ruler, that he was simply being misled by his treacherous ministers and the corrupt Parliament; many thought that if the king could only listen to the colonial plight, he would become sympathetic to their cause and set things right. The first Petition to the King was adopted and sent in 1774 but received no response in the coming months. What the colonists could not have known was that George III already considered the colonies to be in open rebellion and was encouraging his ministry to restore order, with force if necessary.

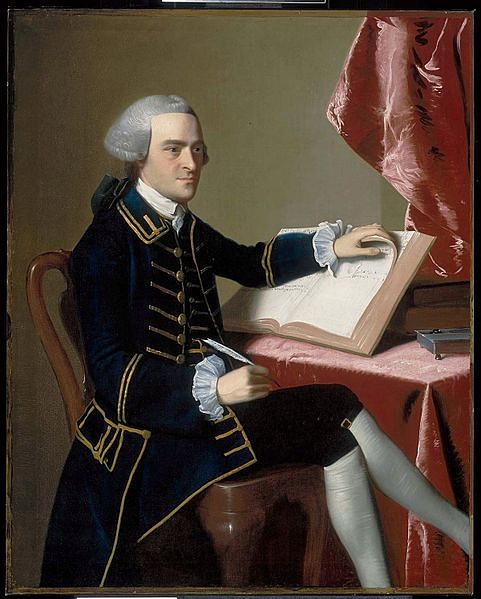

By the time the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in May 1775, first blood had already been spilled at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775) and colonial militias were laying siege to the British troops garrisoned in Boston; on 17 June 1775, the colonists and British soldiers would clash once again at the Battle of Bunker Hill, one of the bloodiest days of the American Revolution. The Second Congress took it upon itself to act as America's wartime government; it dispatched George Washington to take command of the colonial army outside Boston and authorized an American invasion of Quebec. At the same time, many congressional delegates still held out hope for peace and a return to the status quo. George III was seen in a less benevolent light than he had been the previous autumn, but some delegates still believed the king to be the best avenue to negotiate a satisfactory peace. At the very least, Congress hoped that a petition to the king asking for peace would prove to the world that the Americans were not the aggressors and that all they wanted was to defend their liberties from the tyrants in Parliament. John Dickinson was the primary author of what became known as the Olive Branch Petition, although he was advised by Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Rutledge. On 5 July 1775, the petition was signed by the Congress' president, John Hancock, and was sent to London on 8 July.

Olive Branch Petition Text

To the King's Most Excellent Majesty.

Most Gracious Sovereign: We, your Majesty's faithful subjects of the Colonies of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts-Bay, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, the Counties of Newcastle, Kent, and Sussex, on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, in behalf of ourselves and the inhabitants of these Colonies, who have deputed us to represent them in General Congress, entreat your Majesty's gracious attention to this our humble petition.

The union between our Mother Country and these Colonies, and the energy of mild and just Government, produced benefits so remarkably important, and afforded such an assurance of their permanency and increase, that the wonder and envy of other nations were excited, while they beheld Great Britain rising to a power the most extraordinary the world had ever known.

Her rivals, observing that there was no probability of this happy connection being broken by civil dissensions, and apprehending its future effects if left any longer undisturbed, resolved to prevent her receiving such continual and formidable accessions of wealth and strength, by checking the growth of those settlements from which they were to be derived.

In the prosecution of this attempt, events so unfavourable to the design took place, that every friend to the interest of Great Britain and these Colonies, entertained pleasing and reasonable expectations of seeing an additional force and exertion immediately given to the operations of the union hitherto experienced, by an enlargement of the dominions of the Crown, and the removal of ancient and warlike enemies to a greater distance.

At the conclusion, therefore, of the late war [French and Indian War], the most glorious and advantageous that ever had been carried on by British arms, your loyal Colonists having contributed to its success by such repeated and strenuous exertions as frequently procured them the distinguished approbation of your Majesty, of the late King, and of Parliament, doubted not but that they should be permitted, with the rest of the Empire, to share in the blessings of peace, and the emoluments of victory and conquest.

While these recent and honourable acknowledgments of their merits remained on record in the Journals and acts of that august Legislature, the Parliament, undefaced by the imputation or even the suspicion of any offence, they were alarmed by a new system of statutes and regulations adopted for the administration of the Colonies, that filled their minds with the most painful fears and jealousies; and, to their inexpressible astonishment, perceived the danger of a foreign quarrel quickly succeeded by domestic danger, in their judgment of a more dreadful kind.

Nor were these anxieties alleviated by any tendency in this system to promote the welfare of their Mother Country. For though its effects were more immediately felt by them, yet its influence appeared to be injurious to the commerce and prosperity of Great Britain.

We shall decline the ungrateful task of describing the irksome variety of artifices practiced by many of your Majesty's Ministers, the delusive pretenses, fruitless terrors, and unavailing severities, that have, from time to time, been dealt out by them, in their attempts to execute this impolitic plan, or of tracing through a series of years past the progress of the unhappy differences between Great Britain and these Colonies, that have flowed from this fatal source.

Your Majesty's Ministers, persevering in their measures, and proceeding to open hostilities for enforcing them, have compelled us to arm in our own defense, and have engaged us in a controversy so peculiarly abhorrent to the affections of your still faithful Colonists, that when we consider whom we must oppose in this contest, and if it continues, what may be the consequences, our own particular misfortunes are accounted by us only as parts of our distress. Knowing to what violent resentments and incurable animosities civil discords are apt to exasperate and inflame the contending parties, we think ourselves required by indispensable obligations to Almighty God, to your Majesty, to our fellow-subjects, and to ourselves, immediately to use all the means in our power, not incompatible with our safety, for stopping the further effusion of blood, and for averting the impending calamities that threaten the British Empire.

Thus called upon to address your Majesty on affairs of such moment to America, and probably to all your Dominions, we are earnestly desirous of performing this office with the utmost deference for your Majesty; and we therefore pray, that your Majesty's royal magnanimity and benevolence may make the most favourable constructions of our expressions on so uncommon an occasion. Could we represent in their full force the sentiments that agitate the minds of us your dutiful subjects, we are persuaded your Majesty would ascribe any seeming deviation from reverence in our language, and even in our conduct, not to any reprehensible intention, but to the impossibility of reconciling the usual appearances of respect with a just attention to our own preservation against those artful and cruel enemies who abuse your royal confidence and authority, for the purpose of effecting our destruction.

Attached to your Majesty's person, family, and Government, with all devotion that principle and affection can inspire; connected with Great Britain by the strongest ties that can unite societies, and deploring every event that tends in any degree to weaken them, we solemnly assure your Majesty, that we not only most ardently desire the former harmony between her and these Colonies may be restored, but that a concord may be established between them upon so firm a basis as to perpetuate its blessings, uninterrupted by any future dissensions, to succeeding generations in both countries, and to transmit your Majesty's name to posterity, adorned with that signal and lasting glory that has attended the memory of those illustrious personages, whose virtues and abilities have extricated states from dangerous convulsions, and, by securing happiness to others, have erected the most noble and durable monuments to their own fame.

We beg leave further to assure your Majesty, that notwithstanding the sufferings of your loyal Colonists during the course of this present controversy, our breasts retain too tender a regard for the kingdom from which we derive our origin, to request such a reconciliation as might, in any manner, be inconsistent with her dignity or her welfare. These, related as we are to her, honour and duty, as well as inclination, induce us to support and advance; and the apprehensions that now oppress our hearts with unspeakable grief, being once removed, your Majesty will find your faithful subjects on this Continent ready and willing at all times, as they have ever been, with their lives and fortunes, to assert and maintain the rights and interests of your Majesty, and of our Mother Country.

We therefore beseech your Majesty, that your royal authority and influence may be graciously interposed to procure us relief from our afflicting fears and jealousies, occasioned by the system before-mentioned, and to settle peace through every part of our Dominions, with all humility submitting to your Majesty's wise consideration, whether it may not be expedient, for facilitating those important purposes, that your Majesty be pleased to direct some mode, by which the united applications of your faithful Colonists to the Throne, in pursuance of their common counsels, may be improved into a happy and permanent reconciliation; and that, in the meantime, measures may be taken for preventing the further destruction of the lives of your Majesty's subjects; and that such statutes as more immediately distress any of your Majesty's Colonies, may be repealed.

For such arrangements as your Majesty's wisdom can form for collecting the united sense of your American people, we are convinced your Majesty would receive such satisfactory proofs of the disposition of the Colonists towards their Sovereign and Parent State, that the wished for opportunity would soon be restored to them, of evincing the sincerity of their professions, by every testimony of devotion becoming the most dutiful subjects, and the most affectionate Colonists.

That your Majesty may enjoy a long and prosperous reign, and that your descendants may govern your Dominions with honour to themselves and happiness to their subjects, is our sincere and fervent prayer.

(Text sources: American Battlefield Trust; Americainclass.org)

The King's Response

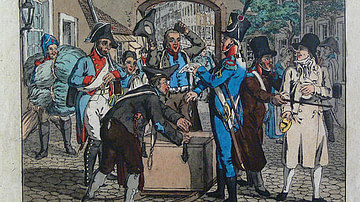

The Olive Branch Petition arrived in London on 21 August 1775, after news of the Battle of Bunker Hill had already reached British newspapers. Reports of the horrendous British losses at Bunker Hill, and the narrative of colonial militiamen fighting like 'savages', had horrified the British public and hardened many of their hearts against their American cousins. In response to the news of the battle, King George III issued a royal proclamation on 23 August in which he officially declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and called for the suppression of said rebellion as well as for the punishment of its leaders (see below for the text of this proclamation). When the king's ministers presented him with a copy of the Olive Branch Petition on 2 September, George III refused to even read it, letting his Proclamation of Rebellion serve as the Crown's official response.

The king's proclamation not only ended a chance at an early peace but also disillusioned the American Patriots that George III was in any way sympathetic to their cause. With the publication of Thomas Paine's influential pamphlet, Common Sense, the following year, many Americans began to believe that severing ties with the Crown altogether was their only hope at securing their liberties. Consequently, there would be no more attempts at reconciliation between Great Britain and its colonies; on 4 July 1776, the United States of America would declare its independence.

Proclamation of Rebellion

Whereas many of our subjects in diverse parts of our Colonies and Plantations in North America, misled by dangerous and ill designing men, and forgetting the allegiance which they owe to the power that has protected and supported them; after various disorderly acts committed in disturbance of the public peace, to the obstruction of lawful commerce, and to the oppression of our loyal subjects carrying on the same; have at length proceeded to open and avowed rebellion, by arraying themselves in a hostile manner, to withstand the execution of the law, and traitorously preparing, ordering and levying war against us: And whereas, there is reason to apprehend that such rebellion hath been much promoted and encouraged by the traitorous correspondence, counsels and comfort of diverse wicked and desperate persons within this realm: To the end therefore, that none of our subjects may neglect or violate their duty through ignorance thereof, or through any doubt of the protection which the law will afford to their loyalty and zeal, we have thought fit, by and with the advice of our Privy Council, to issue our Royal Proclamation, hereby declaring, that not only all our Officers, civil and military, are obliged to exert their utmost endeavors to suppress such rebellion, and to bring the traitors to justice, but that all our subjects of this Realm, and the dominions thereunto belonging, are bound by law to be aiding and assisting in the suppression of such rebellion, and to disclose and make known all traitorous conspiracies and attempts against us, our crown and dignity; and we do accordingly strictly charge and command all our Officers, as well civil as military, and all others our obedient and loyal subjects, to use their utmost endeavors to withstand and suppress such rebellion, and to disclose and make known all treasons and traitorous conspiracies which they shall know to be against us, our crown and dignity; and for that purpose, that they transmit to one of our principal Secretaries of State, or other proper officer, due and full information of all persons who shall be found carrying on correspondence with, or in any manner or degree aiding or abetting the persons now in open arms and rebellion against our Government, within any of our Colonies and Plantations in North America, in order to bring to condign punishment the authors, perpetrators, and abettors of such traitorous designs.

Given at our Court at St. James's the twenty-third day of August, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five, in the fifteenth year of our reign.

God save the King.

(Text source: Massachuetts Historical Society Collections)