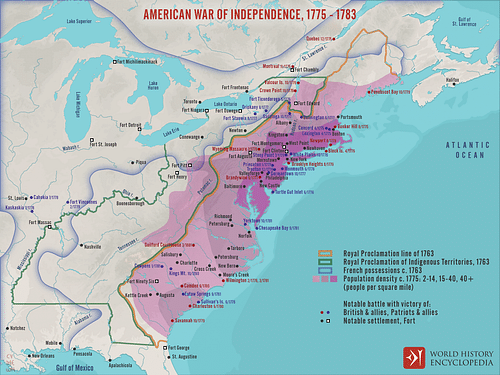

The American invasion of Quebec (September 1775-June 1776) was a military campaign undertaken during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Hoping to induce the Province of Quebec to join the rebellion, the Second Continental Congress dispatched troops under generals Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold to occupy British-controlled Canada. The invasion climaxed with an American defeat at the Battle of Quebec.

The invasion marked the first offensive campaign conducted by the American Continental Army, which occurred despite the Continental Congress' insistence that it was fighting a purely defensive war. It was a two-pronged invasion; a 1,200-man colonial force under General Montgomery left Fort Ticonderoga in September 1775, going on to capture Fort Saint-Jean and occupy Montreal. A second 1,100-man expedition, led by General Arnold, departed from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and arrived at the city of Quebec by way of Maine. Here, Arnold's force linked up with Montgomery's, and the Americans launched an assault on Quebec City on 31 December 1775. The battle went disastrously for the Americans; Montgomery was killed, Arnold was wounded, and the American attack was repulsed.

After the Battle of Quebec, the Americans maintained a half-hearted siege of the city, during which time their army was ravaged by smallpox. As the siege wore on, Canadian Loyalists were able to turn public opinion against the American invaders, leading to unrest in American-occupied Montreal. In May 1776, fresh British troops and Hessian mercenaries under General John Burgoyne arrived in Canada, emboldening Canadian governor Guy Carleton to launch a counteroffensive. As a result, the disease-ridden Continental Army broke off its siege and withdrew to Fort Ticonderoga. The American defeat ended all hopes of Canada joining the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789) and opened a path for General Burgoyne to launch his Saratoga Campaign through New York's Hudson Valley the following year.

Background

When the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, the Province of Quebec was still a relatively new addition to the British Empire. Concentrated along the Saint Lawrence River Valley and extending beyond the Great Lakes to the banks of the Ohio River, the Province of Quebec had been under French control until the French and Indian War (1754-1763), when the city of Quebec was captured by the British after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (13 September 1759). When the Treaty of Paris ended that war in 1763, France officially ceded its Canadian territory to Britain. The Canadians were now subjects to the British Crown, as were the American colonists of the Thirteen Colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. However, the French and Indian Wars had pitted the Canadians and Americans against one another for nearly a century, and those years of bloody warfare were not easily forgotten. The American colonists distrusted their French-speaking, Catholic neighbors to the north.

In 1774, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act, which protected the Canadians' right to practice Catholicism and extended the borders of the Province of Quebec into the Ohio River Valley. Both of these provisions offended the American colonists; the overwhelmingly Protestant Americans feared the encroachment of Catholicism into their lands, while Virginian land surveyors felt cheated out of the Ohio territory, which they felt rightly belonged to them. Yet, at the same time, conflict was mounting between the Thirteen Colonies and the British Parliament, and by autumn, many believed war was inevitable. Despite the generational hatred between the French-Canadians and Americans, the First Continental Congress recognized the value of Canadian support and formally invited the Province of Quebec to join the struggle against British tyranny. The Congress received no answer.

On 19 April 1775, tensions boiled over when the first shots of the American Revolutionary War were fired in Massachusetts at the Battles of Lexington and Concord, which resulted in an American victory. As the colonists began to lay siege to the British forces holed up in Boston, another group of colonial militiamen under Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen captured Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain. In their report to the Second Continental Congress, Arnold and Allen noted that the Province of Quebec was poorly defended by only militia forces and could be occupied by an American army as small as 1,200 men. Both Arnold and Allen requested the honor of leading such a campaign, but the idea was initially dismissed by the Continental Congress, who did not want to appear to be the aggressors in the conflict.

In the meantime, the war continued to escalate; the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775) resulted in horrendous British casualties and greatly reduced the chance for a peaceful compromise. Even as the Congress sent the Olive Branch Petition to London in a last-ditch effort to negotiate a peace, it began to prepare for a protracted conflict, organizing the Continental Army under the command of General George Washington. Some congressional delegates also began to reconsider an invasion of Quebec, especially once it became known that General Guy Carleton, the British governor of Quebec, was strengthening Canadian fortifications and was actively using Canada as a base from which to court the Iroquois Confederacy into siding with the British. In late June 1775, the Congress gave General Philip Schuyler permission to begin planning a Canadian invasion, should an opportunity arise; the hope was that an American invasion would convince Canadian Patriots to rise against the British and join the American cause as the fourteenth colony.

Montgomery's Expedition

General Schuyler immediately began assembling an expedition at Fort Ticonderoga. By August, Schuyler had amassed some 1,200 men, including Ethan Allen and his famous militia, the Green Mountain Boys. Just before the invasion was to begin, however, Schuyler fell ill and handed the command of the expedition off to Major General Richard Montgomery. An Irish-born veteran of the French and Indian War, Montgomery had resigned from the British army in 1772 before settling in New York, where he married into a family of ardent American Patriots. Montgomery was quick to identify as an American and adopt his wife's anti-British beliefs; his political ideology and military experience made him the ideal candidate to lead the attack on Quebec.

General Montgomery led the colonial force out of Ticonderoga on 25 August 1775, where they followed the Richelieu River to Fort Saint-Jean, arriving on 6 September. Fort Saint-Jean sat at the north end of Lake Champlain and guarded the entry into the Province of Quebec. For the next several days, the colonial troops engaged in skirmishes on the outskirts of the fort, in which they battled against Britain's indigenous allies, the bulk of which were comprised of Mohawks. On 17 September, Montgomery officially laid siege to the fort. Hoping to test the theory that the French Canadians would rush to the Americans' aid, Montgomery sent Allen and the Green Mountain Boys to recruit a new militia from the Canadians. Allen, however, had more ambitious plans in mind; believing Montreal to be lightly defended, he attempted to capture the city on 25 September but was defeated at the Battle of Longue-Point and taken prisoner.

Despite this small setback, the siege of Fort Saint-Jean continued with relative ease. British General Carleton could do little to impede its progress; men were deserting from his militias at an alarming rate, and he lacked any British regular soldiers. On 3 November, the fort finally fell to Montgomery's troops. Upon hearing the news, Carleton fled to Quebec City, believing Montreal to be indefensible. Therefore, Montgomery occupied Montreal on 13 November without a fight. Montgomery lingered in Montreal for several days, during which time he published pamphlets in support of the American cause and met with leading American sympathizers to discuss the election of Canadian delegates to the Continental Congress. While in Montreal, the enlistments of many American troops expired, leaving Montgomery with only 500 men. However, emboldened by his recent success, Montgomery decided to push on to Quebec City anyway, despite his depleted force. He took 300 men with him and left Major General David Wooster and 200 troops behind to garrison Montreal.

Arnold's Expedition

As Montgomery pushed on toward Quebec City, a second American expedition was headed for the same destination. Benedict Arnold yearned for more of the glory that he had tasted when he had captured Fort Ticonderoga and asked General Washington for permission to lead a secondary expedition into Canada in support of Montgomery. Washington consented and gave Arnold 1,100 men for the expedition, including Daniel Morgan and his company of riflemen. Setting sail from Newburyport, Massachusetts, Arnold's expedition arrived at the mouth of the Kennebec River in what is today the state of Maine on 19 September 1775. The plan was to reach Quebec City by following the rivers of Maine.

Yet Arnold seems to have underestimated the amount of ground he and his troops would need to travel across. The boats that the men used to travel up the Kennebec were leaky, leading to the spoiling of gunpowder and provisions. The men were nevertheless in good spirits when it came time to exit the Kennebec and carry the 400-pound boats across the Maine wilderness to reach the Chaudière River. However, a combination of abysmal weather and swampy terrain quickly destroyed morale, especially when provisions began to run out in the middle of October. Miserable, drenched, and starving scores of men turned back at this point while others fell sick and were left for dead. By the time Arnold's tired expedition reached the Saint Lawrence River on 9 November, they numbered 675 men, the rest having deserted, died, or been abandoned along the way. Arnold's men finally came to a halt at Pointe aux Trembles, some 20 miles (32 km) from Quebec City, where they were joined in early December by Montgomery and his comparatively cheery troops.

Battle of Quebec

In the weeks that elapsed between the fall of Montreal and the joining of Montgomery's and Arnold's forces at Pointe aux Trembles, General Guy Carleton had been preparing Quebec City for a siege. Carleton had 1,800 men in his garrison, a force that historian Robert Middlekauff describes as "a strange mixture of militia, Scottish soldiers, a handful of marines, and large numbers of sailors drawn from ships in the harbor" (311). Quebec itself was centered around Cape Diamond, located in the confluence between the Saint Lawrence River and its tributary, the Saint Charles. At the bottom of Cape Diamond rested the part of the city known as Lower Town, which was defended by hastily constructed palisades and a blockhouse. The main part of the city, called Upper Town, was protected on three sides by steep cliffs and on the west side by a 30-foot wall that overlooked the Plains of Abraham.

Montgomery, Arnold, and their combined 1,200 men surrounded the city and, on 6 December, began to lay siege. They sent a letter to Carleton demanding his surrender, but the British commander refused, burning the letter without reading it. Carleton knew that time was on his side; he only had to hold out until spring, when the ice of the Saint Lawrence would thaw, allowing British reinforcements to sail up the river to his aid. Additionally, the enlistment contracts of most of the miserable and starving American troops were set to expire at the end of the year, and it was becoming increasingly clear that most of them were not about to reenlist. Montgomery realized that he had to take the city before the new year and decided that his best chance was to wait until a snowstorm, when he could approach Quebec and scale the walls undetected, taking the garrison by surprise. On 27 December, Montgomery got the blizzard he had been waiting for, but by the time he got his men into position, the storm had subsided, and he was forced to call off the assault.

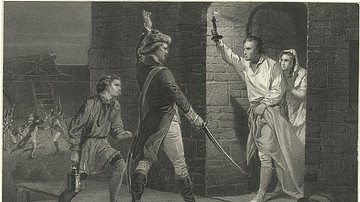

He would get another chance on the night of 30 December, when another heavy blizzard, even worse than the last, struck Quebec. It took Montgomery three hours to get his men into position, and it was not until 2 a.m. on 31 December that they began to move. The plan was to attack Lower Town, where the British defenses were believed to be weakest; Arnold would lead 600 men against the northern side of Lower Town, while Montgomery led 300 men against the southern side. Montgomery's men fired rockets into the air to let Arnold's troops know that it was time to advance, but with visibility low, both groups soon became disorientated and confused in the blinding snow. Montgomery's men finally approached the walls of Quebec at around 5 a.m., but the British sentries spied the bobbing light emanating from the Americans' lanterns. The alarm was raised, and the British opened fire once Montgomery's troops were within close range.

General Montgomery was killed almost instantly, his body shredded by grapeshot fired from a British cannon. His troops wavered and then broke beneath the British volleys, the survivors fleeing back into the dark of the storm. To the north, Arnold's men were also discovered and were greeted by several volleys from the British muskets; though the Americans could not effectively return fire due to the height of the wall, they held their ground and eventually managed to breach the wall. Arnold was wounded in the leg, leaving Daniel Morgan to take command as the Americans streamed into Lower Town. Morgan's men fought valiantly but soon became confused when there was no sign of Montgomery or his men; the revelation that Montgomery had been defeated caused Morgan's men to panic, which Carleton was quick to take advantage of. The British counterattacked and engaged the Americans in street-to-street fighting. By 9 a.m., the battle was done. Over 400 Americans had been captured, including Morgan, with an additional 80 having been killed or wounded. The British suffered only 19 casualties.

Siege of Quebec

Despite the Americans' humiliating defeat, Arnold was not ready to give up quite yet. He pulled back about a mile from Quebec to regroup and wait, as reinforcements began to filter in from the colonies. Before long, he encircled Quebec City and once again began to lay siege. But Carleton had taken advantage of the lull by procuring more supplies and could now hold out for months. The condition of Arnold's wound worsened, forcing him to give up his command and return to Montreal, where he was replaced by General David Wooster. The siege continued with relatively little development until Carleton's attempt to break the siege was squandered at the minor Battle of Saint-Pierre (25 March 1776).

By this point, the Continental Congress had dispatched thousands of reinforcements to Quebec, including the experienced Major General John Thomas, who assumed overall command. However, the American army was soon ravaged by smallpox, which incapacitated a large portion of the soldiers, of whom many eventually died, including General Thomas himself. Additionally, discontent was festering in American-occupied Montreal; during his administration of the city, General Wooster had made many enemies by jailing suspected Loyalists and forcing several communities to surrender their arms. The Canadians also came to despise the American troops, who paid for services with their own paper money rather than in hard British currency. In April 1776, a delegation from the Continental Congress arrived to assess public opinion in Canada. The delegation, which included Benjamin Franklin, found the population to be largely disposed against the Americans; since the whole point of the invasion had been to whip up Canadian support for the American Revolution, this was a troubling discovery.

The final nail in the coffin came in late May, when British General John Burgoyne arrived in Canada with thousands of fresh troops that included Hessian auxiliaries, mercenaries from the German principalities of Hesse-Cassel and Hesse-Hanau. The arrival of these fresh forces encouraged Carleton to launch a counteroffensive, and he defeated the Americans at the Battle of Trois-Rivières (8 June), taking many of them prisoner. The remnants of the American army withdrew back down the Richelieu River toward Ticonderoga, while Arnold oversaw the evacuation of Montreal. By July 1776, the Americans had left Canadian soil, ending their invasion in failure.

Aftermath

The American Invasion of Quebec was the first major defeat that the Americans suffered in the Revolutionary War. It was a disastrous initiative that cost them many lives, including those of Richard Montgomery and John Thomas, two of their best commanders. It also ended all hope that the Province of Quebec might join the war on the American side, as it affixed Canada squarely in the arms of the British. One immediate consequence of the campaign's failure was that it positioned General Burgoyne and his British army to begin the Saratoga Campaign the following year, in which he would move down from Canada and into New York's Hudson River Valley. This would be one of the most decisive campaigns in the war, culminating in the Battles of Saratoga.