The Battle of Fort Washington (16 November 1776) took place during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) as part of the British effort to seize control of Manhattan Island. It saw a British and Hessian force capture Fort Washington, near the northern end of Manhattan at modern-day Washington Heights, in one of the worst American defeats of the war.

Fort Washington was constructed in the summer of 1776 as part of General George Washington's plan to defend Manhattan from the British. When the Continental Army was eventually pushed out of Manhattan during the New York and New Jersey Campaign (July 1776 to January 1777), Washington left a garrison of troops behind in the fort to maintain a toehold on the island. On 16 November 1776, the fort came under attack by the British army under General William Howe, with the main assault being led by the Hessians, professional German mercenaries fighting for the British. After the Americans were pushed back from their outer defenses, they capitulated, surrendering Fort Washington and its garrison of 2,800 men, who became prisoners; three-quarters of these prisoners would die aboard the infamous British prison ships anchored off Brooklyn. The Battle of Fort Washington was a costly American defeat that deprived the Continental Army of men and supplies at a time when it was running dangerously low on both.

Construction of the Fort

On 13 April 1776, General George Washington arrived in Manhattan at the head of his 19,000-man Continental Army. He had long feared that New York City would be the next target of the British; its capture would allow the British unimpeded access to the Hudson River, which could allow them to sail an army into the American interior. Washington decided to construct a series of fortifications near the hamlet of Brooklyn on Long Island, anticipating that the British would have to take Long Island before advancing to New York City, which was at the time entirely confined to the upper part of Manhattan Island.

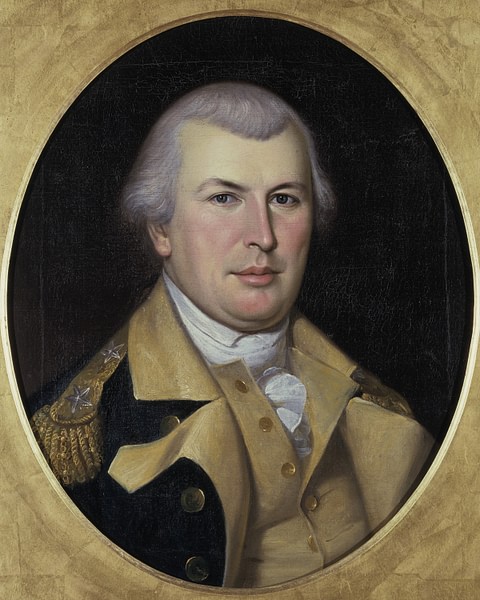

Should the defense of Long Island fail, Washington desired to fortify the Hudson itself to impede British progress up the river. In June, Washington sent General Nathanael Greene, one of his most trusted subordinates, to scout for potential positions to build a fort. After surveying the terrain, Greene settled on a hill at the highest part of Manhattan, near the island's northernmost point; in Greene's opinion, the position would be easy to defend if fortified properly. Washington gave his approval, agreeing that the spot was the key to the Hudson's defense, and a Pennsylvania regiment immediately got to work constructing the fort, under General Greene's supervision. By the end of July, the fort was finished and was named Fort Washington.

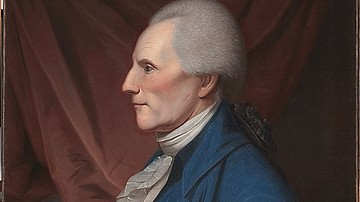

Greene also oversaw the construction of a secondary fortification on the opposite side of the river, atop the New Jersey Palisades; originally named Fort Constitution, the New Jersey fort was eventually renamed to Fort Lee in honor of Washington's second-in-command, General Charles Lee. With Fort Washington guarding the east side of the Hudson and Fort Lee on the west, it seemed the strategically valuable river might be safe from British control, the idea being that both forts could unleash a devastating crossfire bombardment on any British ship that attempted to sail up the river. To prevent British ships from simply racing past the forts, the Americans sunk hulks of ships loaded with boulders in the middle of the Hudson, creating a barrier that would block the British vessels and make them more vulnerable to the forts' cannons. This type of barrier is known as a chevaux de frise.

As for the design of Fort Washington itself, it was a pentagon-shaped earthwork fortification covering four acres of land, its walls made of rock and piled up dirt. An imposing spectacle sitting on a 250-foot-high (76 m) hill, the fort was not as secure as it may have seemed. It had no barracks for the men, had no ditches and palisades for additional defense, and, crucially, it had no water supply; though the garrison could haul water up from below, the fort's lack of water storage would be disastrous in the event of a siege. General Greene, who became temporarily incapacitated by illness during Fort Washington's construction, did not notice these critical defects.

The British Invade New York

In early July 1776, at the same time the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia was declaring the independence of the United States, a British and Hessian expeditionary force under General William Howe was disembarking on Staten Island in New York harbor. By early August, this force numbered 32,000 men, making it the largest expeditionary army Great Britain had yet sent out in any part of the world; by contrast, Washington's ragged and disease-ridden army numbered less than 10,000 effectives. On 22 August, General Howe landed 15,000 men on Long Island and assaulted the American position on the Heights of Guan five days later; the resulting Battle of Long Island was a catastrophe for the Americans, who lost nearly 3,000 men killed, wounded, or captured. Following the defeat, Washington prudently decided to evacuate Long Island during the night of 29-30 August, pulling his entire army back to New York City; henceforth, the defense of Manhattan Island would be Washington's main concern.

On 15 September, the British and Hessians made an amphibious landing at Kip's Bay on Manhattan, meeting minimal resistance. That same day, Washington abandoned New York City and positioned his troops atop Harlem Heights (modern-day Morningside Heights) at the northwestern part of Manhattan Island. General Howe occupied New York City before attempting to force Washington off the heights, but the overconfident British troops were checked at the Battle of Harlem Heights (16 September). The Continental Army maintained its position on the heights for the next month, with relatively little fighting. However, on 18 October, the British landed 4,000 troops at Pelham in the Bronx, intending to flank the Continental Army and trap it. Rather than risk being encircled and seeing his army destroyed, Washington decided to withdraw even further to Westchester County, even though this would require him to give up Manhattan.

Before Washington gave the order to retreat, he was approached by General Greene, who still believed that Fort Washington was nearly impenetrable. Greene implored his superior to keep the fort garrisoned; this way, the Americans could maintain a toehold on Manhattan and pin down British troops that could otherwise be used to attack New Jersey. Most importantly, Greene argued that if the British wished to take Fort Washington, they would have to assault it uphill, which could lead to a repeat of the slaughter of British troops that had occurred a year earlier at the Battle of Bunker Hill under similar circumstances. Washington was skeptical of these arguments, but his trust in Greene caused him to set aside his better judgment. While most of the Continental Army withdrew to White Plains, Washington ordered 2,000 troops under Colonel Robert Magaw to remain behind at Fort Washington, which, along with Fort Lee, was now the only obstacle between the British and control of the Hudson.

Preparations

Initially, the British ignored the garrison of Fort Washington, opting instead to pursue the Continental Army into Westchester County. After defeating Washington at the relatively minor Battle of White Plains (28 October), British General Howe decided it was time to complete his occupation of Manhattan; Howe began to march back south on 5 November. Two days later, Howe had established his headquarters 6 miles (10 km) above King's Bridge and was preparing an attack on Fort Washington. It was then that Howe was approached by William Demont, an American officer-turned-traitor, who provided the British with plans of the fort as well as the placement of its cannons. Furthermore, Demont told Howe that the Continental troops were miserable and disgruntled.

On 15 November, General Howe sent an officer to Fort Washington under a flag of truce with a simple message: surrender now, or the entire garrison would be put to the sword. Informed that he had two hours to make a decision, Colonel Magaw responded that he needed no time to think, telling the British officer, "Give me leave to inform his Excellency that, activated by the most glorious cause that mankind ever fought in, I am determined to defend this post to the last" (Middlekauff, 359). Magaw's bold response had been made in good faith; the colonel trusted that his garrison could hold out for at least a month and that the British would pay dearly in blood if they tried to assault the fort before then. The officer took Magaw's reply back to General Howe, who began preparing for an attack.

Meanwhile, an anxious Washington had arrived at Fort Lee on the opposite side of the river, having left his army encamped at Hackensack, New Jersey. After learning about Howe's ultimatum and Magaw's reply, Washington also learned that Nathanael Greene had already appraised the situation at Fort Washington and had dispatched an additional 900 men to aid in the garrison's defense. The garrison, according to Greene's subsequent report, was in "high spirits and would make a good defense" (McCullough, 240). Washington, however, still felt uneasy; the loss of Fort Washington would lead to the loss of a good portion of his army. With his army shrinking daily from desertion and disease, he could not spare a single man.

Washington and Greene decided to spend the night at Fort Lee and figure out what to do about Fort Washington in the morning. When the sun rose on Saturday 16 November, Washington got in a small boat, intending to cross the Hudson River and visit the garrison at Fort Washington himself; he was accompanied by three of his generals including Greene, Israel Putnam, and Hugh Mercer. Their boat was almost across the river when the roar of cannon fire echoed from the direction of Fort Washington, alerting them that the British assault had begun. The generals landed just downriver from the fort, taking shelter in a building called the Morris house.

The British Attack

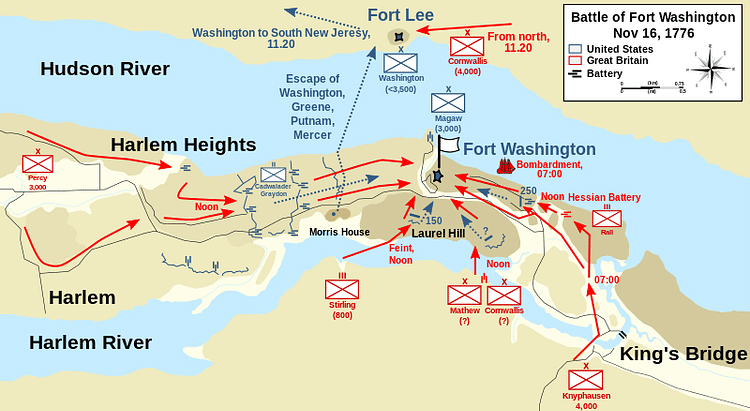

The British battle plan was for a three-pronged assault on Fort Washington. The German General Wilhelm von Knyphausen would lead 4,000 Hessian soldiers in an attack from the north over the King's Bridge; this was to be the main attack, which Knyphausen had requested the honor of personally leading. A secondary battalion of Hessians, led by the British General Lord Hugh Percy, would simultaneously advance from the south while a third force of British light infantry, led by Lord Charles Cornwallis, would strike from the east, moving across the Harlem River in flatbottom boats. Meanwhile, the 42nd Highlanders, the infamous Scottish infantry regiment better known as the Black Watch, would make a feint attack from the Harlem River, hoping to draw some Americans toward the shoreline and away from the other points of assault. In all, the British and Hessians had around 8,900 men to commit to the attack; Magaw's garrison numbered roughly 2,800.

Around 7 a.m. on 16 November, British and Hessian artillery began to bombard Fort Washington from multiple directions, including from British ships in the Harlem River. The Black Watch was delayed in crossing the Harlem, however, meaning that the British were unable to launch their ground assault until noon; by then, the Americans had had hours to prepare. When General Knyphausen's Hessians reached the fort's outer defenses, they were met with rifle fire from Maryland and Virginia regiments under Lieutenant Colonel Moses Rawlings. As the American riflemen took shots at them from behind trees, the Hessians struggled to climb the steep, rocky slopes. They quickly started taking casualties and were driven back twice, but the Hessians were professional soldiers and their discipline held out. On their third charge, they reached the top of the slope; one Hessian soldier, John Reuber, recorded:

At last, however, we got about on top of the hill where there were trees and great stones. We had a hard time of it there together. Because they had no idea of yielding, [Hessian] Colonel Rall gave the word of command thus: 'All that are my grenadiers, march forwards!' All the drummers struck up the march, the [oboe] players blew. At once, all that were yet alive shouted, 'Hurrah!' Immediately, all were mingled together, Americans and Hessians. There was no more firing, but all ran forward pell-mell upon the fortress (McCullough, 241-242).

While the Americans and Hessians grappled at the fort's northern defenses, Lord Percy's men moved up from the south. Percy came within 200 yards of the fort's southern defenses, manned by a Pennsylvania regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Lambert Cadwalader when he stopped; Percy was waiting for the Highlanders to make it across the Harlem River to begin their feint attack. When Cadwalader noticed the notorious Black Watch making its way across the river, he sent men to the shoreline to oppose them, thereby weakening his own line. The feint having succeeded, Percy resumed his attack, driving Cadwalader's Pennsylvanians off their outer defenses and into Fort Washinton itself. The men sent to contest the Highlanders' landing were likewise chased into the fort. Lord Percy captured the Morris house; luckily for the Americans, Washington and his officers had been convinced to flee the house only 15 minutes before it fell into Percy's hands. Washington, Greene, and the others were soon rowed across the Hudson back to Fort Lee.

Once the southern and eastern defenses had crumbled, Rawlings' riflemen began to break as well; they were soon also driven into Fort Washington. As the Hessian vanguard, under Colonel Johann Rall, pushed forward, a Pennsylvanian cannoneer named John Corbin was killed. Rather than see the cannon fall to the Hessians, John's wife, Margaret Corbin, took over the cannon, loading it and firing. Margaret was wounded in the arm, chest, and jaw before finally abandoning her post, winning her the respect of both her fellow Americans and the Hessians. Despite the severity of her wounds, Margaret Corbin survived; she would later be the first woman to receive a military pension from the United States Congress and was also recognized as the first woman battle casualty of the American War of Independence.

The Fort Falls

By 1 p.m., the Americans had been driven from the outer defenses and into Fort Washington itself, a space much too small to accommodate the over 2,000-man garrison. With little room to move, let alone fight, the American defenders were confused, tired, and on the verge of panic; it soon became clear to Colonel Magaw that, if the Hessians breached the wall, a massacre would ensue. Indeed, he does not seem to be far off in this assessment; Colonel Rall and his vanguard of Hessians had suffered many casualties and desired vengeance on the Americans. They were restrained only by the efforts of Rall's superior, General Knyphausen, who forbade them from entering the fort without orders. Had Rall not been kept back, one British officer wrote, "the carnage would then have been dreadful, for the rebels were so numerous they had not room to defend themselves with effect, and so frightened they had not the power" (McCullough, 244).

At 2 p.m., General Knyphausen demanded the fort's unconditional surrender. When Magaw dithered, General Howe arrived in person and repeated these demands, promising the Americans their lives if they surrendered. At 3 p.m., Magaw formally capitulated and marched his men out of the fort; passing between two lines of Hessians, the Americans threw down their weapons and became prisoners of war. In the battle, the Americans had lost 59 killed, 96 wounded, and 2,837 prisoners. Most of these prisoners would end up on the infamous British prison ships anchored off Brooklyn, where three-quarters of them would die from the harsh conditions; only 800 survived long enough to be released in a prisoner exchange 18 months later. The British, meanwhile, lost 28 killed and around 100 wounded at the Battle of Fort Washington, while the Hessians lost 58 killed and over 250 wounded.

Aftermath

The loss of Fort Washington was a devastating blow for the Americans. Washington supposedly wept as he watched the fort fall from across the river, while General Greene wrote, "I feel mad, vexed, sick, and sorry…this is a most terrible event. Its consequences are justly to be dreaded" (McCullough, 244). In addition to being pushed out of Manhattan, the Americans had lost nearly 3,000 troops who could not easily be replaced; indeed, the rate of desertions only increased after the dismal news of Fort Washington's fall. On 20 November, Lord Cornwallis led 4,000 British troops across the Hudson, landing 6 miles (10 km) above Fort Lee. Rather than risk another disaster, Washington ordered the garrison to evacuate; Cornwallis captured the empty fort only hours after the last Americans had fled.

Cornwallis continued to pursue Washington through New Jersey, eventually chasing him across the Delaware River and into Pennsylvania in December. The British and Hessians then settled into winter quarters, leaving Washington time to regather and reassess. Realizing he had to win a victory or risk the disintegration of his army, Washington recrossed the Delaware on Christmas Day 1776, and defeated the Hessians at the Battle of Trenton the following day; he would win a follow-up victory at the Battle of Princeton on 3 January 1777. These victories saw the reversal of the Continental Army's misfortunes, although the Battle of Fort Washington would remain one of the worst American defeats of the war.