In June of 323 BCE, Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) died in Babylon. His sudden death before his 33rd birthday has long been a point of speculation: was it disease, old wounds, or murder? Regardless of the cause, history ranks him as one of the greatest of all military commanders, and he "remains the touchstone by which those who embrace the profession of arms measure all things" (Tsouras, xi).

Military Success

Alexander's success can be traced to the foresight of his father, Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE). Aside from an education in the military arts – Alexander excelled with the sword, javelin, and bow – he benefitted from the teachings of a number of gifted tutors, including the Athenian philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE). However, the army that Alexander led across the Hellespont in 334 BCE differed greatly from the one inherited by Philip in 359 BCE. Philip reinvented an infantry considered by most to be untrained and undisciplined. After Philip's death in 336 BCE, the young king had to prove his mettle to both the people of Greece and the men under his command.

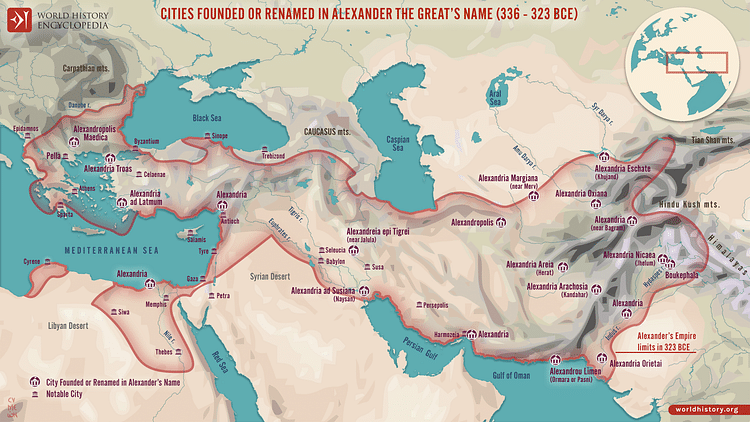

Barely 21 years old and with the reassurance of the Oracle at Delphi, he led his Macedonian army into Asia. He would go on to defeat the Persians at the Battle of Granicus (334 BCE), the Battle of Issus (333 BCE), and the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE). Besides his victories over the Persian Achaemenid Empire, Alexander also defeated the Indian King Porus at the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE), establishing an empire that extended from Greece and Asia Minor through Mesopotamia and into India and Egypt. In 324 BCE, he finally returned to Susa, where he initiated plans for a future expedition into Arabia; he would never live to make it.

Changes in the Government

Alexander began to contemplate how to govern his vast empire. Among his long-term proposals was to integrate the Greek and Persian cultures, which was not well received by his loyal Macedonians. A significant transformation came at the king's court, where his demeanor and attitude had noticeably changed. Anthony Everitt, in his Alexander the Great, wrote that Alexander wanted to unify court practices to ensure that Macedonians and Persians felt equal in his presence. Personally, he began to adopt Persian customs, such as donning the traditional Persian purple and white tunic and wearing a diadem. He sat on an elevated, gold throne surrounded by guards. He began to require people to prostrate themselves before him (proskynesis). While the Persians agreed to the practice because it was their custom, the Greeks refused. To them, Alexander was mortal; he was not a god. The court historian Callisthenes' refusal cost him his life.

As his fellow Macedonians began to see changes in Alexander's court, a sense of discontent began to emerge. There were even rumors of a mutiny or conspiracy to assassinate him. This discontent experienced another boost when Alexander proposed the marriage of his officers (91 of them) to Persian wives. To add to this slap in the face, the ceremonies were Persian, not Macedonian. Aside from his wife Roxanne, the king himself took two Persian wives: one was the daughter of Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE). According to Everitt, this was another example of how the "empire could be governed only with Persian cooperation" (353). This dissatisfaction soon erupted.

At Opis on the Tigris, Alexander supervised the removal of dams that had been built by the Persians. He took the opportunity to address the troops and announce that he was sending home the old and unfit for service; the men stood silent and then became outraged. To them, it was another indication that they were being replaced. They were all aware of the influx of Persian "barbarians" into the army and knew more were forthcoming. 30,000 Persian youth were being trained in Greek and schooled in Macedonian fighting techniques. Unwilling to listen to the king's speech, the men spoke out. Alexander leaped off his platform and demanded to see the instigators: 13 were identified and immediately executed, chained, and thrown into the Tigris. Peace only returned when the men appealed to Alexander.

Death of Hephaestion

Escaping the summer heat, Alexander sought refuge at his palace at Ecbatana, where a music and athletic festival was held. Both Alexander and Hephaestion partied, and both fell ill with a fever. Alexander was placed on a strict diet regimen and recovered. Hephaestion did not; he died in October 324 BCE. Alexander was inconsolable. For failing to cure his patient, Hephaestion's doctor, Glaucius, was crucified. A temple to the Greek god of healing Asclepius was torched. A state of mourning was declared, sacrifices were made, and sacred fires were lit.

Still in mourning, Alexander left the city and returned to Babylon. As he neared the city walls, the king was approached by Chaldean seers who warned him not to enter the city from the west, for it would be disastrous for him; he ignored their warnings. The historian Arrian (86 to c. 160 CE), in his The Campaigns of Alexander, wrote that the seers "begged him to go no further because their god Bel had foretold that if he entered the city at that time it would be fatal to him" (376). He added, "The truth was that fate was leading him to the spot where it was already written that he should die" (377).

While he wrestled with the warnings of the seers and made plans for the expedition into Arabia, he was forced to reconcile problems in Macedon. Tension had continued to grow between his mother Olympias (c. 375-316 BCE) and the regent Antipater (c. 399-319 BCE). She refused to respect Antipater's authority, claiming he was acting more like a king, while he disliked her constant interference, calling her a shrew. Alexander's simple solution was to send the aging and ill Craterus to Macedon, replacing Antipater. Antipater was then instructed to gather reinforcements and march them to Babylon. However, Antipater believed this was a possible death sentence: Did Alexander believe his mother's accusations? Although Alexander had promised him that he was to be honored upon his arrival, Antipater chose an alternate solution: he sent his eldest son Cassander (l. c. 355-297).

Death of Alexander

Alexander now spent his days organizing the details of his Arabian expedition, but his nights were filled with banquets and drinking binges. One evening, he was invited to a party at the home of a friend, Medius of Thessaly, but after feeling a pain in his chest, he returned to his bed. Feeling feverish, his health quickly began to deteriorate, but he ignored both the pain and fever and continued working through the day and partying at night. After another night partying with Medius, he returned home. Still feeling feverish, the following morning, he made his usual sacrifices to the gods, although he had to be carried on a litter. Over the next few days, he continued his usual routine of sacrificing to the gods and holding meetings with his officers, believing he would soon recover. Arrian confirmed what was written in the royal diaries about Alexander's last days; he drank with Medius twice but later took a bath, ate, and went straight to sleep "with the fever already on him" (395).

Despite reassurances that he was still alive, the men believed him to already be dead, so they were permitted to file past him as he lay on his bed. The fever and pain continued to escalate, and eventually, he lost his ability to speak. Arrian wrote that, as his condition grew desperate, he was moved to his palace. "He recognized his officers when they entered his room but could no longer speak to them" (393). On 10 June 323 BCE, Alexander the Great died.

Rumors of Poisoning

Immediately after his death, rumors began to circulate that Alexander had not died of old wounds or a fever but was poisoned. However, these rumors soon subsided while the successors began to divide the empire among themselves. The Wars of the Diadochi soon followed, and it took almost five years for the rumors to resurface. One of the supposed conspirators was the regent Antipater. Having sent his son Cassander to Babylon instead of going himself, he feared he might be put to death for disobeying the king. A second suspect was the king's old tutor Aristotle, who had not forgotten Alexander's murder of Callisthenes. According to the rumor, Cassander and his younger brother Iolaus, the king's cupbearer, were chosen to carry out the poisoning with the poison provided by Aristotle. Cassander had a personal grudge against Alexander. When he arrived in Babylon, he was led before the king, but when he saw the Persians bowing before Alexander, he laughed. An angry Alexander grabbed him by his hair and slammed his head against a wall.

The poisoning supposedly took place at Medius' party, who was Iolaus' lover. After drinking the poisoned wine, Alexander screamed in pain. Hoping to force himself to vomit, he called for a feather, which, given to him by Iolaus, was also laced with poison. Although he wanted to drown himself in the Euphrates, Roxanne took him to his bed. The following morning, upon asking for a drink of water, he was again poisoned. He died quickly.

The conspiracy theory involving Antipater and Aristotle can easily be dismissed. Arrian wrote: "I am aware that much has been written about Alexander's death, for instance, that Antipater sent him some medicine which had been tampered with and that he took it with fatal results… I do not wish to appear ignorant of these stories but stories they are." (394-95) Even the renowned historian Plutarch, in his Life of Alexander, dismissed many of the rumors concerning the king's death, especially the rumor of poisoning.

Modern historians also think that Antipater and Aristotle had little if any serious reason to poison Alexander, and more importantly, past experience had taught Alexander to be well aware of potential conspiracies and plots; a poison such as strychnine could easily be detected. Everitt points out that Alexander had been weakened by his many battle wounds, especially the arrow that punctured his lung. A combination of a weakened constitution and the possibility of malaria was too much for the king to overcome.