The Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777) was a small, yet significant, battle of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) in which the American Continental Army surprised and defeated a British force at Princeton, New Jersey. The battle saved New Jersey from British occupation and, alongside the previous American victory at Trenton, helped galvanize renewed support for the American Revolution (1765-1789).

Background: Victory at Trenton

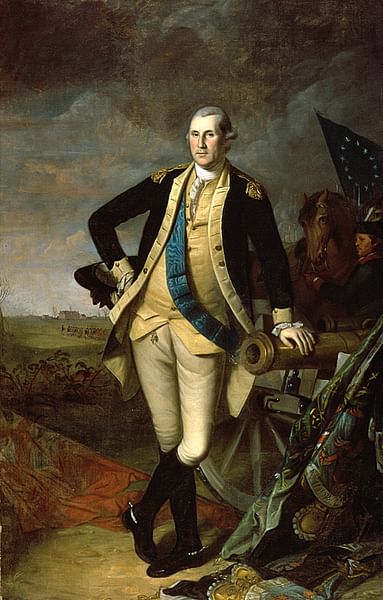

On the cold and stormy night of 25 December 1776, General George Washington led 2,400 Continental soldiers and militiamen across the icy Delaware River, in a desperate gambit to surprise the Hessian garrison at Trenton and save the American Revolution. It had, thus far, been a disheartening campaign season for the Continental Army, which had been in a near-constant state of retreat since its initial defeat at the Battle of Long Island four months earlier. Having first been driven out of New York City and then out of Manhattan altogether, the Americans were then chased out of New Jersey by a British force under Lord Charles Cornwallis, who had pledged to catch Washington just as a "hunter bags a fox" (McCullough, 253).

Already demoralized by the retreat, the American troops were forced to march through sleet and driving rain without shoes or adequate coats and were suffering from malnutrition and disease. The enlistments of most of the men who had not yet deserted were set to expire in the new year, and considering the miserable condition of the army, Washington was unlikely to persuade many of them to reenlist. There was a very real chance that the Continental Army would simply evaporate in the new year, leaving the newly independent United States defenseless against British subjugation.

It was imperative, therefore, that Washington win a substantial victory soon, to convince both the nation and his own soldiers that the Continental Army was still capable of success. The British army had already settled into winter quarters, under the dual assumptions that the fighting season was over and that the Continental Army was too weak to pose much of a threat. A battalion of around 1,500 Hessians, professional German soldiers hired by Britain, was stationed at the town of Trenton, New Jersey; by planning his attack for the morning after Christmas, which the Germans were known to celebrate with particular gusto, Washington hoped to take the garrison by surprise. After crossing the Delaware amidst a howling winter storm, the Americans embarked on a harrowing 9-mile (15 km) march to Trenton, which caused the deaths of two men from exposure. By 8 a.m. on 26 December, the Americans were in position outside Trenton. Concealed from the Hessian sentries by the still-ongoing storm, Washington gave the order to attack.

Immediately, an American column under General Nathanael Greene charged out of the woods, unleashing a musket volley on the Hessian sentries and driving them back into the town. The beating of drums drew the rest of the Hessians out of their quarters, half-dressed and disorientated, just in time for a second American column under General John Sullivan to run into them, sticking them with frostbitten bayonets. As the melee developed, the Hessian commander, Colonel Johann Rall, was mortally wounded and the Hessian field gun was captured, causing most of the Germans to stop fighting and throw down their arms. After less than 45 minutes, the Battle of Trenton was over; 21 Hessians had been killed, 90 had been wounded, and around 900 were taken prisoner. The Americans had suffered only four men wounded and none killed, aside from the two men who had frozen to death prior to the battle. It was an astounding victory for the Americans, just the kind of battle that Washington had desired. The victors gathered up their prisoners and the captured weapons and ammunition before slipping back across the Delaware and into Pennsylvania. But there was still one final chapter of the New York and New Jersey Campaign that remained to be played out.

American & British Reaction

Within days of Trenton, Patriot newspapers had carried word of the unlikely American victory far and wide; before long, every American knew about Washington's daring crossing of the Delaware and the climactic surprise assault on the Hessians. The Second Continental Congress lauded the conduct of the Continental Army and heaped praise upon its commander; in an address to Washington written on behalf of the entire Congress, John Hancock told the general that the victory was all the more "extraordinary" considering that it was won by soldiers who had been "broken by fatigue and ill-fortune" and that "the United States are indebted for the late success of your arms" (McCullough, 284). The victory even impressed the French foreign ministry, which was already supplying the Americans with financial support and was keeping a close eye on the war.

The British, for their part, dismissed the whole affair as a minor skirmish and placed the blame on the now-deceased Colonel Rall, who was conveniently not around to defend himself, but the wealthy and influential New York Tories (or Loyalists) were enraged, unable to understand why the British had not decisively defeated Washington by now. Sir William Howe, commander-in-chief of the British army, was likewise furious; he canceled Lord Cornwallis' leave to England, ordering him instead to return to New Jersey and deal with the Continental Army once and for all. Rousing his men from their winter quarters, Cornwallis set out for Trenton, the last known location of Washington's army, with 8,000 soldiers. As far as the British were concerned, the last American victory had been nothing more than a fluke, and the time of reckoning was coming.

Battle of Assunpink Creek

Washington, meanwhile, had not remained on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River for long. Having stayed just long enough to drop off the prisoners and gather additional forces, Washington crossed the Delaware for a third time on 29 December and ordered a defensive line built at Assunpink Creek, just to the south of Trenton. Washington now faced a problem: in only three days, the enlistments of almost all his soldiers were set to expire. On 30 December, he assembled all 7,000 of his troops and delivered an impassioned speech in which he entreated them to reenlist for at least another month:

My brave fellows, you have done all I asked you to do, and more than can reasonably be expected, but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with fatigues and hardships, but we know not how to spare you. If you will consent to stay on one month longer, you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you can probably never do under any other circumstance.

(McCullough, 286)

6,000 of the Continental soldiers agreed to reenlist; surely, their sense of patriotism was heightened by a bounty of ten dollars that Washington promised to pay any man who signed on again (their usual pay was six dollars a month). Having once again saved the Continental Army from obliteration, Washington could now turn his attention toward the approaching British. On 1 January 1777, Lord Cornwallis reached the town of Princeton, New Jersey, where he spent the night. The next day, Cornwallis left part of his force behind to garrison Princeton while he led the remaining 5,500 soldiers down the 10-mile road to Trenton. Washington had anticipated this and had sent militiamen to churn the Princeton Road to mud to slow the British advance. As the British slowly trudged through the muck, they came under fire from parties of Pennsylvania and Virginia troops, further hindering their advance. As a result, Cornwallis did not reach Trenton until late in the afternoon, at which point the Continental Army had securely dug in along the ridge of Assunpink Creek.

Hoping to take advantage of the few slivers of daylight that remained, Cornwallis ordered an immediate assault. A battalion of Hessian grenadiers was sent to take the stone bridge over the Assunpink, which was defended by a brigade of Virginians; the Virginians were ordered to aim for the legs of the Hessians so that the Hessians would be forced to waste even more daylight by evacuating their wounded comrades to safety. When this first wave of Hessian grenadiers was repulsed, Cornwallis sent in the British regulars. Three times, the British assaulted the bridge, but each time they were driven back by American musket fire and canister shot; one American eyewitness recalled that "the bridge looked red as blood, with their killed and wounded and red coats" (mountvernon.org, Second Trenton). The fighting came to a stop with the onset of darkness, but despite the day's setbacks, Cornwallis remained convinced that Washington had nowhere to go. Once again invoking the imagery of a fox hunt, Cornwallis told his officers that they would "bag" Washington in the morning (McCullough, 287).

Perhaps Cornwallis' self-description as a fox hunter was apt since Washington was quickly proving himself to be as cunning as a fox. The American commander-in-chief waited until most of the British soldiers were asleep and then slipped away on a recently constructed road with 5,500 of his men; he left behind several hundred men to keep the campfires going and to make a lot of noise to maintain the illusion of a bustling army camp. These men, too, slipped away with the approach of dawn, and when the sun rose Cornwallis was greeted with the sight of an empty camp across the Assunpink. Washington, that wily fox, had escaped the hunter's grasp yet again.

Battle of Princeton

Washington had yet another trick up his sleeve. Rather than retreating further south, as might have been expected, he had marched around Cornwallis' army, planning to strike the British rearguard at Princeton, thereby cutting off Cornwallis' line of communication to the British headquarters at New York City. It was another daring maneuver, one that appeared to have gone off flawlessly; by dawn on 3 January 1777, the Continental Army was approaching the outskirts of Princeton. Hoping to prevent Cornwallis from learning of the impending attack until it was too late, Washington sent a detachment of 350 soldiers under Brigadier General Hugh Mercer to destroy the bridge over Stony Brook, on the road to Trenton. The rest of the army pressed on toward Princeton, with General Sullivan's division in the lead.

Princeton was garrisoned by 1,200 British regular soldiers from the 17th, 40th, and 55th regiments of foot, as well as some light dragoons. The night before, Cornwallis had written to the commander of the Princeton garrison, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood, ordering him to march to Trenton at first light to join the main army in preparation for the assault on Assunpink Creek. Therefore, at the same time that Mercer's detachment was advancing up Saw Mill Road toward the Stony Brook Bridge, Colonel Mawhood was leaving Princeton and marching in the same direction. Mawhood spotted the Americans before they could spot him; thinking fast, Mawhood ordered the 4th Brigade back into town and sent his light skirmishers forward to hold the Americans in place. The British skirmishers took up positions behind a fence in William Clarke's orchard and fired a volley at Mercer's troops when they passed by.

The British volley went too high, however, allowing Mercer's men time to wheel around and face the enemy. The two sides exchanged fire as additional British troops began rushing toward Clarke's orchard with fixed bayonets; Colonel Mawhood himself led the 17th regiment into the fray, his pair of springer spaniels running at his side. The Americans, though outnumbered, held their ground for more than ten minutes, until they were overwhelmed by a British bayonet charge. Mercer himself was soon surrounded but refused several calls to lay down his arms; in response, he was bayoneted seven times before being left for dead. Since Mercer was clearly an experienced officer, and was well-dressed, the British believed that they had just killed Washington himself. Colonel John Haslett, Mercer's second-in-command, tried to rally the Americans but was killed by a shot to the head.

Just as Mercer's now leaderless troops were about to break, they were reinforced by 1,100 militiamen from General John Cadwalader's brigade; Washington had noticed the battle at Clarke's orchard unfold and had sent Cadwalader to hold the British down. Before long, more than 2,000 American troops had joined the battle, descending on the British flanks. Washington himself was soon on the scene, riding up and down the battle line, waving his hat and shouting encouragements; the sight of their commander-in-chief exposing himself to danger awed the Americans and inspired them to keep fighting. Before long, the British had turned and were fleeing back toward Princeton. Washington spurred his horse and led the pursuit, yelling back to his men: "It's a fine fox chase, my boys!" (McCullough, 289). The hunted had, indeed, become the hunter.

By the time the Continental Army had entered Princeton itself, most of the British soldiers, including Colonel Mawhood, had escaped. However, around 200 stubborn British troops remained behind, holed up inside Nassau Hall, the main stone building at the center of what was then New Jersey College (modern-day Princeton University). The British hoped to keep the Americans occupied long enough for Cornwallis to arrive, thereby trapping the Americans in the town. Washington, however, was not about to give them that chance. He ordered Captain Alexander Hamilton to aim a few field guns at the building, and after several rounds were fired, the British decided they had had enough and hoisted a white flag out of one of the windows (the damage done to Nassau Hall in Hamilton's brief bombardment can still be seen today). The 194 surviving British soldiers exited the building and gave up their weapons.

The Americans had lost around 30 dead (including Colonel Haslett and General Mercer, who died of his wounds on 12 January) and about 45 wounded. British losses have been more difficult to determine; in his official report, Washington claimed that the British had lost 100 killed and 300 captured, while British General Howe reported 18 killed, 58 wounded, and 200 missing.

Aftermath

Washington did not linger in Princeton for long, as he knew that Cornwallis was on his way. After stopping just long enough to loot the British supply wagons, the Continental Army marched to Somserset Courthouse, where it spent the night. Two days later, it was encamped on the hilly and wooded terrain near Morristown, New Jersey, where it would spend the remainder of the winter. Rather than try to assault Washington's strong defensive position at Morristown, General Howe decided to greatly reduce British presence in New Jersey and pulled most of his men back into New York. Aside from some small-scale yet brutal skirmishes between American and British foraging parties, the fighting between the two armies would not resume until the summer. The New York and New Jersey Campaign (July 1776 to January 1777), which had at one point looked so bleak for the American cause, was over.

Although the American victory at the Battle of Princeton was not as complete as the one at Trenton had been, it had a massive effect disproportionate to its size. It galvanized renewed support for the American Revolution, with Patriot newspapers citing it as evidence that the war was, after all, winnable. Hundreds of men were inspired to enlist in the Continental Army, ensuring that it was strong enough to fight in the upcoming Philadelphia Campaign of 1777-78. Additionally, the battles of Trenton and Princeton brought New Jersey back under Patriot control; only a few weeks earlier, many were predicting that New Jersey would become the first state to resubmit to the British Empire. Princeton was, therefore, one of the most significant battles of the war, contributing to the eventual American victory six years later.