During the European Enlightenment, a concept was developed in philosophy and aesthetics called the sublime. In the arts, literature, and the works of intellectuals, the sublime referred to the awe-inspiring capacity of nature and beauty, characteristics that artists and thinkers sought to replicate in their own work and even to apply to ethics.

The concept of the sublime involves the inherent conflict which comes from an appreciation of beauty with a feeling of awe, astonishment, and incomprehension of the eternal. Philosophers discussed this conflict and suggested that our aim should be the harmonious blending of reason with emotion, and so the sublime became an element of the great shift during the Enlightenment which saw reason come to replace religion as the dominant driving intellectual force.

Origins of the Sublime

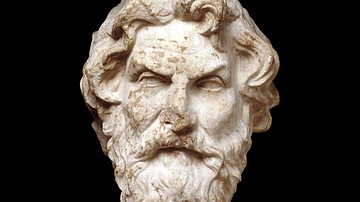

The idea of the sublime was revitalised during the Enlightenment thanks to the translation of an ancient text by Boileau in 1672. This text, only rediscovered in 1554, was On the Sublime, then thought to have been written by Longinus, a Greek author of the 1st century CE. J. W. Yolton summarises Longinus' thoughts on the sublime as:

…that quality which gives a distinctive power to works of art and literature; it rest primarily on grandeur of ideas and the capacity for strong emotion, supplemented by certain features of rhetoric; sublimity is the echo of a noble mind and a passionate heart.

(508)

Although he is primarily concerned with poetry and oratory, Longinus also writes about the sublime in nature and how impressive natural features and phenomena like wide plains, rugged mountains, and powerful rivers can bring out in all (or most) of us a pleasure at beholding them and a clearer sense of and proximity to the divine.

The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy gives the following definition of the sublime: "The sublime is great, fearful, noble, calculated to arouse sentiments of pride and majesty, as well as awe and sometimes terror" (462-3). The sublime then creates a strange mixture of feelings like pleasure, awe, anxiety, personal insignificance, and even fear and terror; think of one's mixed emotions, for example, when standing above a precipice gazing down on a majestic Norwegian fjord.

The idea of the sublime in nature and the arts would capture the imagination of many writers, artists, and philosophers during the Enlightenment. The sublime, with its focus on immense grandeur and unfathomable meanings, seemed at odds with the progress being made by science where discovering nature's laws and order were the objectives of knowledge. Philosophers attempted to reconcile this conflict between emotion and reason and to show that the mind can indeed triumph over nature. A wide range of Enlightenment thinkers considered the sublime as part of their philosophy but here, in the interests of space and clarity, we will consider only three.

Burke on the Sublime

In England, in particular, writers and literary critics began to highlight the sublime, either in travel experiences or in their criticism of existing great works. Paradise Lost by John Milton (1608-1674), published in 1667, was frequently described as the greatest example of the sublime in the English arts. It did not take long for the philosophers to turn their penetrating analysis to this old-but-new concept. The sublime was most famously assessed by Edmund Burke (1729-1797) in his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, published in 1757. Burke was looking for rather more of an explanation of the sublime than "nature's beauty" or "art's beauty", and so he analysed what exactly might produce this feeling, separating beauty from its causes. In this work, Burke "explores the nature of 'negative' pleasures, that is, irrational and mixed feelings of pleasure and pain, of attraction and terror" (Yolton, 72). As Yolton summarises, "Burke finds the sources of the sublime in qualities such as obscurity, power, vacuity, darkness, solitude, silence and vastness, which convey ideas of pain and terror without causing physical danger" (508). For Burke, the sublime is ultimately the interaction between reason and emotion. While beauty is defined as things which are ‘pretty', the sublime describes a complex pleasure which carries with it a flavour of danger or anxiety. Burke states:

Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotions which the mind is capable of feeling.

(Robertson, 507)

The historian S. Blackburn describes the significance of Burke's work: "[It] marked a very early Romantic turn away from the 18th-century aesthetic of clarity and order, in favour of the imaginative power of the unbounded and infinite, and the unstated and unknown" (66). Burke was challenging the idea that reason was always the best faculty to deal with the world and expand our knowledge of it. Reason was a cornerstone of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment movement, but Burke, nevertheless, insisted that emotion (what we today might call intuition or creative imagination) had a place in the learning process. Burke wrote:

Whatever turns the soul inward on itself, tends to concentrate its forces and to fit it for greater and stronger flights of science. Whenever the wisdom of our Creator intended that we should be affected with any thing, he did not confine the exercise of his design to the languid and precarious operation of our reason; but he endued it with powers and properties that prevent [i.e anticipate] the understanding, and even the will, which seizing upon the senses and imagination, captivate the soul before the understanding is ready either to join with them or to oppose them.

(Hampson, 193)

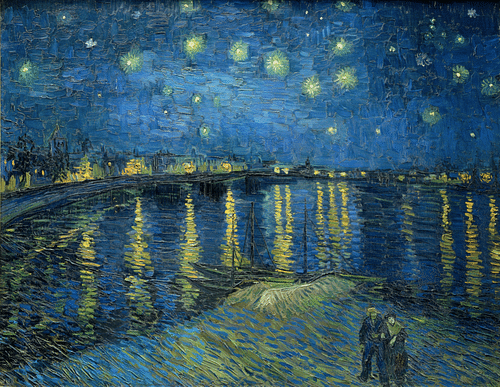

Burke goes on to give an example of something that evokes the sublime, a starry sky:

The starry heaven, though it occurs so very frequently to our view, never fails to excite an idea of grandeur. This cannot be owing to any thing in the stars themselves, separately considered. The number is certainly the cause. The apparent disorder augments the grandeur, for the appearance of care is highly contrary to our ideas of the magnificence. Besides, the stars lie in such apparent confusion, as makes it impossible on ordinary occasions to reckon them. This gives them the advantage of a sort of infinity.

(Robertson, 508)

Burke suggests that in the arts, a little obscurity is a good thing when trying to conjure up the sublime. He notes that paintings are often too clear and sometimes look a little false or even ridiculous; he gives the example of trying to portray hell in an oil painting. Literature, and especially poetry, says Burke, is, therefore, more effective at communicating the sublime because the reader's imagination is left to fill the gaps. This idea that the exercise of the mind is all-important to the sublime was further pursued by the next philosopher to tackle the concept.

Kant on the Sublime

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was greatly interested in the sublime, although he was inclined towards its possibilities regarding ethics. In 1764, Kant published Observations on the Beautiful and Sublime. Another work in which he discusses aesthetics is Critique of Judgement, published in 1790. Kant presents the view that experiencing the sublime is a matter of intuition; it is a subjective experience, and so he shifts the focus away from what causes or contains the sublime to each individual's emotional and intellectual makeup that determines their specific reaction. Kant observed that by using our minds to overcome the immensity of nature's power, or at least to create some sort of harmony between reason and emotion, the sublime "raises the soul above the height of vulgar commonplace" (Blackburn, 463). This is all very well contemplating nature from the comfort of an armchair; those who have seen a vast mountain range from a high peak or the power of a tumultuous ocean in a fearsome storm might argue that it is nature which usually triumphs. Kant would argue, though, that because the mind is superior to all physical things, the sublime must really be found in the non-physical. The sublime is the human reaction to the physically impressive or beautiful, above all, it is the exercise and mastery of ourselves as moral beings.

Wollstonecraft on the Sublime

Another thinker keen to delve into the sublime was Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797). Travelling through Scandinavia, she wrote of a classic sublime experience in her Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, published in 1796. In the following passage, she describes her reaction to an impressive waterfall, encapsulating in a practical experience the same ideas that Burke and Kant had alluded to in theory:

Reaching the cascade, or rather cataract, the roaring of which had a long time announced its vicinity, my soul was hurried by the falls into a new train of reflections. The impetuous dashing of the rebounding torrent from the dark cavities which mocked the exploring eye, produced an equal activity in my mind: my thoughts darted from earth to heaven, and I asked myself why I was chained to life and its misery? Still the tumultuous emotions this sublime object excited, were pleasurable; and, viewing it, my soul rose, with renewed dignity, above its cares – grasping at immortality – it seemed as impossible to stop the current of my thoughts, as of the always varying, still the same, torrent before me – I stretched out my hand to eternity, bounding over the dark speck of life to come.

(Robertson, 510)

Legacy

The sublime, with its idea of blending emotion and reason in a single experience, greatly influenced Romanticism, the art movement which lasted from around 1775 to 1830, where emphasis was given to new forms and modes of expression. Romanticism was entirely less formal in rules and structure, more spontaneous, and much more emotional compared to what had gone before. Romanticism favoured Kant's interpretation of the sublime as a personal affair since artists now specifically sought to move the individual who interacted with their work. This ambition would be continued by later movements such as impressionism, neo-impressionism, and symbolism. To paraphrase Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), art must no longer copy nature but act like nature. In short, if a mountain could conjure up the sublime, so could a painting or sculpture.

Another related movement, also associated with the 19th century, is aestheticism. Championed by such artists as Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), aestheticism proclaimed that the most noble aim of human existence is to appreciate art and beauty. Further, neither art nor beauty should ever be restricted by moral considerations since these two things do not have (or should not have) any particular moral or political objective.

The idea of the sublime beauty and power of nature helped shape another new way of thinking, often called environmental ethics. Here, nature is valued for its own sake, irrespective of any real or potential use to humanity. Not being able to appreciate this value, even though it is difficult to quantify and articulate, is deemed an aesthetic failure.