Black Elk Speaks (1932) is the popular and controversial book of the narrative by the Oglala Lakota Sioux medicine man Black Elk (l. 1863-1950) on his life and people as given to the American poet and writer John G. Neihardt (l. 1881-1973). Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877), Black Elk's second cousin, is among the many featured in the work.

According to Black Elk, his father and Crazy Horse's father were cousins, making him and Crazy Horse second cousins. In chapter 7 of Black Elk Speaks, the narrative pauses to focus on Black Elk's relationship with Crazy Horse and the great warrior's vision, name, and reputation. This section of the work is of great interest to historians writing on Crazy Horse, or to anyone with an interest in him, as it presents an intimate portrait of a man who is famous for keeping to himself.

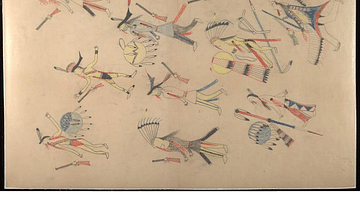

Although Crazy Horse participated in the Battle of Platte Bridge in 1865, Red Cloud's War (1866-1868), led war parties between 1868-1876, including at the Battle of the Rosebud and the Battle of the Little Bighorn, little is known of the man himself. He never allowed himself to be photographed or sketched – so, to this day, no one knows what he looked like – and is depicted by Black Elk, and others, as a solitary figure who, as Black Elk notes, was most comfortable in his teepee, in the presence of children, and with members of a war party, but rarely spoke to people or participated in festivals.

Many other narratives on Crazy Horse, such as that of the Sioux author and physician Charles A. Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa, l. 1858-1939), are not first-person accounts, while Black Elk's is. Even though Black Elk gave his story to Neihardt in 1930-1931, and Crazy Horse was murdered at Fort Robinson in 1877, Black Elk's narrative is still understood as an eyewitness account of the events and people it deals with.

Neihardt's book is considered controversial, however, as some scholars, notably anthropologist Raymond J. DeMallie (l. 1946-2021), have claimed Neihardt adjusted Black Elk's actual narrative for wider appeal to a white audience. DeMallie, an expert on Lakota Sioux culture and language, notes that Neihardt did not speak the language and received the narrative through an interpreter. It is possible, then, that Neihardt misunderstood certain terms or concepts presented by Black Elk. Even so, the work is still regarded as an important historical document on the lives of the Sioux in the 19th century and many of the most famous figures of that time.

Background to the Crazy Horse Passage

The events Black Elk relates in the Crazy Horse passage in chapter 7 take place in 1875 when Black Elk was 12 years old. Red Cloud's War had concluded with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which included, among many others, the promise by the US government that the Black Hills would be Sioux land "as long as the grass should grow and the rivers flow."

In 1874, however, gold was found in the Black Hills by an expedition led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876), and the treaty was ignored. Miners, settlers, and soldiers began appearing in the Black Hills and this influx would eventually turn into the Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876.

Custer's discovery and the appearance of the miners and others is what Black Elk is referring to below as the "bad trouble" and "trouble coming." The "Hang-Around-The-Fort people" he alludes to in the first paragraph are followers of Red Cloud. Some Sioux resented Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909) for making peace with the white man and looked down on his followers, who were regularly engaged in trade with the white merchants at sites like Fort Laramie. They were derisively referred to as "Hang-Around-The-Fort people" as they seemed to prefer associating with the white man and would no longer fight to defend Sioux lands, unlike Crazy Horse and his warriors.

Earlier in Chapter 7, Black Elk describes the arrival of the white men in the Black Hills and how the Sioux held a council to decide how to respond:

I asked my father what they were talking about in there, and he told me that the Grandfather at Washington [President of the United States] wanted to lease the Black Hills so that the Wasichus [white men] could dig yellow metal, and that the chief of the soldiers had said if we did not do this, the Black Hills would be just like melting snow in our hands, because the Wasichus would take that country anyway.

It made me sad to hear this. It was such a good place to play, and the people were always happy in that country…After the council, we heard that creeks of Wasichus were flowing into the Hills and becoming rivers, and that they were already making towns up there. It looked like bad trouble coming, so our band broke camp and started out to join Crazy Horse on Powder River.

(50-51)

Shortly after this, the Crazy Horse passage begins.

Text

The following is taken from Black Elk Speaks: The Complete Edition by John G. Neihardt, University of Nebraska Press, 2014, pp. 51-54.

On Kills-Himself Creek, we made more meat and hides and were ready to join Crazy Horse's camp on the Powder River. There were some Hang-Around-The-Fort people with us and, when they saw that we were going to join Crazy Horse, they left us and started back to the Soldiers' Town. They were afraid there might be trouble and they knew Crazy Horse would fight, so they wanted to be safe with the Wasichus. We did not like them very much.

We had no advisers, because we were just a little band, and when we were moving, the boys could ride anywhere. One day, while we were heading for Powder River, I was riding ahead with Steals-Horses, another boy my age, and we saw some footprints of somebody going somewhere. We followed the footprints and there was a knoll beside a creek where a Lakota was lying. We got off and looked at him and he was dead. His name was Root-of-the-Tail, and he was going over to Tongue River to see his relatives when he died. He was very old and ready to die so he just lay down and died right there before he saw his relatives again

Afterwhile, we came to the village on Powder River and went into camp at the downstream end. I was anxious to see my cousin, Crazy Horse, again, for now that it began to look like bad trouble coming, everybody talked about him more than ever and he seemed greater than before…

Of course, I had seen him now and then ever since I could remember and had heard stories of the brave things he did. I remember the story of how he and his brother were out alone on horseback and a big band of Crow [Indians] attacked them. So that they had to run. And while they were riding hard, with all those Crows after them, Crazy Horse heard his brother call out; and when he looked back, his brother's horse was down, and the Crows were almost on him. And they told how Crazy Horse charged back right into the Crows and fought them back with only a bow and arrows, then took his brother up behind him and got away. It was his sacred power that made the Crows afraid of him when he charged. And the people told stories of when he was a boy and used to be around with the older Hump [his mentor] all the time. Hump was not young anymore at the time and he was a very great warrior, maybe the greatest we ever had until then. They say people used to wonder at the boy and the old man always being together; but I think Hump knew Crazy Horse would be a great man and wanted to teach him everything.

Crazy Horse's father was my father's cousin and there were no chiefs in our family before Crazy Horse; but there were holy men; and he became a chief because of the power he got in a vision when he was a boy. When I was a man, my father told me something about that vision. Of course, he did not know all of it; but he said that Crazy Horse dreamed and went into the world where there is nothing but the spirits of all things. That is the real world that is behind this one, and everything we see here is something like a shadow from that world. He was on his horse in that world, and the horse and himself on it and the trees and the grass and the stones and everything were made of spirit, and nothing was hard, and everything seemed to float.

His horse was standing still there, and yet it danced around like a horse made only of shadow, and that is how he got his name, which does not mean that his horse was crazy or wild, but that in his vision it danced around in that queer way.

It was this vision that gave him his great power, for when he went into a fight, he had only to think of that world to be in it again, so that he could go through anything and not be hurt. Until he was murdered by the Wasichus at the Soldiers' Town on White River, he was wounded only twice, once by accident and both times by someone of his own people when he was not expecting trouble and was not thinking, never by an enemy. He was fifteen years old when he was wounded by accident; and the other time was when he was a young man, and another man was jealous of him because the man's wife liked Crazy Horse.

They used to say too that he carried a sacred stone with him, like one he had seen in some vision, and that when he was in danger, the stone always got very heavy and protected him somehow. That, they used to say, was the reason no horse he ever rode lasted very long. I do not know about this; maybe people only thought it; but it is a fact that he never kept one horse long. They wore out. I think it was only the power of his great vision that made him great.

Now and then he would notice me and speak to me before this; and sometimes he would have the crier call me into his teepee to eat with him. Then he would say things to tease me, but I would not say anything back, because I think I was a little afraid of him. I was not afraid that he would hurt me; I was just afraid. Everybody felt that way about him, for he was a queer man and would go about the village without noticing people or saying anything. In his own teepee, he would joke, and when he was on the warpath with a small party, he would joke to make his warriors feel good. But around the village he hardly ever noticed anybody, except little children.

All the Lakota like to dance and sing; but he never joined a dance, and they say nobody ever heard him sing. But everybody liked him, and they would do anything he wanted or go anywhere he said. He was a small man among the Lakota, and he was slender and had a thin face and his eyes looked through things and he always seemed to be thinking hard about something. He never wanted to have many things for himself and did not have many ponies like a chief.

They say that when game was scarce and the people were hungry, he would not eat at all. He was a queer man. Maybe he was always part way into that world of his vision. He was a very great man, and I think if the Wasichus had not murdered him down there, maybe we should still have the Black Hills and be happy. They could not have killed him in battle. They had to lie to him and murder him. And he was only about thirty years old when he died.

One day, after we had camped there on Powder River, I went upstream to see him again, but his teepee was empty and he was gone somewhere, maybe with a war party against the Crows, for we were close to them now and had to look out for them all the time. Later I did see him. He put his arm across my shoulder and took me into his teepee and we sat down together. I do not remember what he said, but I know he did not say much, and he did not tease me. Maybe he was thinking about the trouble coming.

We did not stay together there very long, but scattered out and camped in different places so that the people and the ponies would all have plenty. Crazy Horse kept his village on Powder River with about a hundred teepees, and our band made camp on the Tongue. We built a corral of poles for the horses at night and herded them all day, because the Crows were great horse-thieves and we had to be careful. The women chopped and stripped cottonwood trees during the day and gave the bark to the horses at night. The horses liked it and it made them sleek and fat.