The Batavia was a Dutch East India Company ship that foundered on the coral reefs of the Houtman Albrolhos Islands, 60 kilometres (37 mi) off the coast of Western Australia, just before dawn on 4 June 1629. It was the flagship of a fleet of seven vessels that set sail for the Dutch East Indies in October 1628.

It was the ship's maiden voyage. On board were around 340 passengers and crew, including soldiers, women and children, and high-ranking company officials en route to the Dutch entrepôt or trading centre of Batavia (modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia).

Survivors of the Batavia were ferried to what is now known as Beacon Island, situated within an archipelago of 122 islands at the northern tip of the Houtman Albrolhos. The ordeal that followed the Batavia's wreck is a dark tale in maritime history. A group of mutineers massacred an estimated 125 people during a reign of terror that lasted until a rescue ship arrived from Batavia in September 1629.

The Fleet Departs

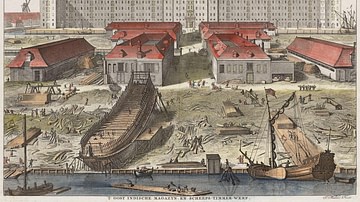

The Batavia was a 600-ton retourschip or 'return ship' belonging to the Amsterdam chamber of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC)). This type of vessel was the workhorse of the VOC fleet, built for the perilous sea journey between the Netherlands and the East Indies and with a considerable cargo capacity.

The Batavia was 46 metres (150 ft) in length and carried a cargo of twelve chests of silver coin worth 250,000 guilders, trade goods, including cochineal, cloth, wines, and cheeses, and a valuable gem from antiquity known as the Constantine Cameo. The VOC had been granted the right to trade exclusively in Asia and obtain spices by the States General of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. The silver coin was for the purchase of nutmeg, mace, and cloves, and the gem may have belonged to the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), who hoped to sell it to Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605-1627), the fourth Mughal emperor. To protect against pirates and the English and Portuguese, the Batavia had 24 cast-iron cannons and 100 soldiers, who were mainly German mercenaries.

The governor-general of the colony of Batavia, Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587-1629), wrote to the Board of Directors of the VOC in 1618, arguing that the wives and children of VOC employees in the colony should be allowed to journey to Batavia. The women and children on board the Batavia, including 27-year-old Lucretia van der Mijlen (1602-1641), an upper-class woman who would join her husband, were to start a new life in the East Indies thanks to Coen.

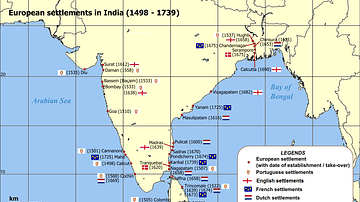

The Batavia set sail from Texel in the Netherlands on 29 October 1628. The commander of the fleet of seven ships was Francisco Pelsaert (c. 1595-1630) from Antwerp, who had been the VOC's representative in Agra, India. He returned to the Netherlands in 1628, having contracted a fever that would kill him two years later. Most likely, he was given command of the fleet because his brother-in-law was Hendrick Brouwer (1581-1643), the eighth governor-general of the East Indies (1632-1636) and notable for developing a faster route (the Brouwer Route) to the East Indies in 1611 via the Cape of Good Hope.

The captain of the Batavia was Adriaen Jacobsz, one of the oldest men on board and in charge of navigation. Little is known of Jacobsz, other than that he had quarrelled with Pelsaert ten years earlier in India, and the tension between the two men would ultimately lead to the Batavia's fate. Jeronimus Cornelisz (c. 1598-1629), a 30-year-old Dutch apothecary and bankrupt merchant who had recently signed on with the VOC, was the opperkoopman or supercargo, the person responsible for managing the cargo and the commercial interests of the company. Cornelisz would become the leader of the mutineers. The sea voyage would take nine gruelling months on board a crowded, rat-infested ship with only four latrines for over 300 people.

The first sign of trouble occurred after a stopover for fresh water and supplies at the Cape of Good Hope when a power struggle broke out between Pelsaert and Jacobsz. The fleet commander accused Jacobsz of drunkenness and for harassing Lucretia van der Mijlen and molesting her maid, Zwaantie Hendrix. Jacobsz was reprimanded by Pelsaert, who was then laid low for a month by the fever he had contracted in India. This gave Jacobsz time to do two things: the first was to separate the Batavia from the rest of the fleet so they could not intervene, and the second action was to foment a mutiny, take over the ship and its treasure, and throw Pelsaert overboard.

Mutineers & Shipwreck

Jacobsz found allies in Cornelisz and a small group of men who planned to provoke a still-recovering Pelsaert into taking harsh disciplinary action that would spread discontent among the entire crew. Lucretia van der Mijlen was their target, and one night on deck, eight masked men attacked, smearing the woman with tar and excrement. An enraged Pelsaert carried out an investigation. Lucretia recognised one of her attackers, which suggested to the commander that Jacobsz was behind the shocking incident, but given the escalating tension, Pelsaert decided to delay his verdict until they reached Batavia.

Disaster struck, however, when the Batavia crashed into Morning Reef in the Wallabi Group, the northernmost group of islands in the Houtman Abrolhos. Pelsaert's doubt about the captain's navigational skills may have had a basis. A miscalculation in dead reckoning, which could place a ship wildly off course, may have led to the loss of the Batavia. Dead reckoning was a navigation method used by sailors during the Age of Exploration to determine a ship's approximate position based on its previous position, course, and speed.

After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, VOC ships would follow the Brouwer Route east, taking advantage of the Roaring Forties in the southern Indian Ocean before turning north at a hypothetical point and heading to the East Indies, some 3,218 kilometres (2,000 mi) away. This route cut six months off the journey from Europe, but it relied on estimating the distance travelled and location through dead reckoning in order to avoid the treacherous coastline of Western Australia.

Unfortunately, the last reckoning taken by Jacobsz was incorrect. He estimated the Batavia to be 965 kilometres (600 mi) off the Australian coast when, in fact, the ship was only 64 kilometres (40 mi) from its fate. In the early morning hours of 4 June 1629, a lookout saw waves breaking on the coral reefs of the Houtman Abrolhos, but Jacobsz assumed it was the reflection of the moon on the water and did not change course. The Batavia became impaled on Morning Reef.

Pelsaert's journal, which was published in 1647, describes the chaos:

Fourth of June, being Monday morning, on the 2 day of Whitsuntide, with a bright clear full moon about 2 hours before daybreak during the watch of the skipper, I was lying in my bunk feeling ill and felt suddenly, with a rough terrible movement, the bumping of the ship's rudder, and immediately after that I felt the ship held up in her course against the rocks, so that I fell out of my berth. Whereon I ran up and discovered that all the sails were in top, the wind south west, the course north east by north during that night, and were lying right in the middle of a thick spray. Round the ship there was only a little surf, but shortly after that one could hear the sea breaking hard round it. I said, skipper what have you done, that through your reckless carelessness you have run this noose round our necks.

(Quoted in The Batavia Journal of Francisco Pelsaert)

The crew desperately attempted to unballast the ship by removing anything weighing it down – cannons were pushed overboard and the mast was cut down. Their frantic attempts were unsuccessful and heavy swells pounded the Batavia for nine days before it broke apart. It was one of Australia's earliest European shipwrecks.

Reign of Terror

Around 40 people drowned when the Batavia hit the reef. A 9-metre (30 ft) longboat and a small yawl, which could carry 50 passengers between them, took survivors to Beacon Island, a small treeless coral islet that is 0.8 kilometres (0.5 mi) in length and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from the wreck. Some sailors and officers landed on another nearby island that would later be called Traitor's Island. More than 40 men decided to stay on board and raid the stores of wine, including Jeronimus Cornelisz, who also had a fear of water.

The survivors' immediate problem was a lack of fresh water and food supplies. Jacobsz headed a search party and took the longboat and yawl, but given the captain's behaviour on the sea voyage, Pelsaert did not trust him and decided to join the search for food and water. It was a fruitless search, and the decision was made to attempt the perilous 3,000-kilometre (1,864 mi) voyage in the longboat and with the yawl to the VOC trading post of Batavia. When the survivors on Beacon Island woke the following day, they found their leaders had abandoned them. Within days, people started drinking salt water and urine, and around 20 people died.

As the Batavia broke apart, Jeronimus Cornelisz was forced to swim to Beacon Island, where he found around 200 people in desperate need of a leader. Cornelisz was said to have a charismatic personality and was an eloquent speaker. He was also a religious fanatic, following the beliefs of Anabaptism. As the highest-ranking sailor left, Cornelisz seized control, commandeered the limited water and food supplies, and gathered all the weapons and makeshift rafts.

What happened next is a study of barbarism. On the pretext that Beacon Island lacked space, Cornelisz sent a group of 40 men, women, and children to nearby Seals' Island (also called Long Island). He hoped they would die of thirst and hunger. Under the command of Wiebbe Hayes (b. c. 1587), a soldier from Groningen, 23 soldiers were sent to an island now called West Wallabi to remove the threat of the German mercenaries. Their mission was to find water and Cornelisz promised they would be picked up at a later time.

To consolidate absolute power back on Beacon Island, Cornelisz and men loyal to him executed a soldier who had stolen wine and began to eliminate the population in order to conserve supplies or dispose of anyone who questioned his authority. No one was spared. The sick were targeted first, while stronger survivors had their throats cut during the night. Total obedience to Cornelisz did not guarantee survival. For this reason, this islet became known to history as Batavia's Kerkhof (Batavia's Graveyard). Accounts vary, but the final murderous toll is estimated at 125 people, including children.

Rescue & Trials

Some survivors managed to escape Beacon Island and made their way to West Wallabi. After hearing of the atrocities, Hayes fortified his camp, making weapons from Batavia's debris. Seals' Island had fresh water and plenty of food, mainly wallabies and seabirds. Cornelisz soon realized Hayes was a threat, and in August 1629, the self-styled "Captain General," who wore Plesaert's elegant clothing, launched one of three attacks on Seals' Island. During the final raid in September, when Cornelisz tried to negotiate a peace treaty with Hayes, he and four of his men were captured.

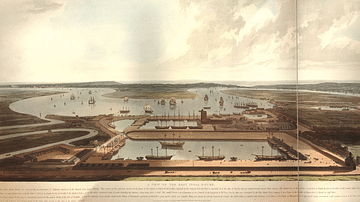

On September 17, help arrived. It had taken the longboat one month to reach Batavia. Francisco Pelsaert met with the governor-general Jan Pieterszoon Coen, who provided Pelsaert with a jacht, the Sardam, a fast sailing ship primarily used for carrying messages or transporting high-ranking VOC officials. Coen ordered the commander to salvage what he could from the Batavia's cargo. Adriaen Jacobsz was accused of negligence while in command of the Batavia and thrown into a dungeon, where he is believed to have died.

The Sardam, with its captain and 25 crew, took three weeks to reach the archipelago but spent another month trying to find Beacon Island. Fortunately, Wiebbe Hayes was the first to sight the Sardam appearing over the horizon and sent a small makeshift craft to intercept it.

Seals' Island became a temporary prison for Jeronimus Cornelisz and his mutineers before they were brought to trial for their crimes. The island gained the name Traitor's Island.

Cornelisz was tortured. Under Dutch law in the 17th century, torture was permitted to obtain confessions and secure convictions. Francisco Pelsaert led the investigation after forming a council. Cornelisz initially confessed, then recanted, but was condemned to hang on 2 October 1629, after having both hands amputated. Six of his loyal mutineers insisted their leader be the first to die in case he evaded his fate. Two men, including a cabin boy named Pelgrom, were marooned on the Australian mainland as punishment and never heard from again.

After recovering almost all the treasure chests, Pelsaert returned to Batavia in December 1629 with 16 of the mutineers, who were tried and executed. Wiebbe Hayes was considered a hero and promoted to the rank of standard-bearer. Pelsaert died in September 1630, never quite able to shake the accusation that he had abandoned the survivors without water. He was also accused of engaging in private trade, and when his widow applied for his outstanding salary, the VOC refused to pay out.

The ordeal of Batavia's survivors was a sensation in Europe, retold in The Unlucky Voyage of the Batavia, a book published in 1647 that included Pelsaert's journal entries, survivor accounts, and mutineers' confessions. It confirmed in the Dutch mind that the Australian coastline was inhospitable and should be avoided.

Rediscovery of the Batavia

The wreck of the Batavia was discovered in 1963 around 74 kilometres (45 mi) from Geraldton, Western Australia, when a lobster fisherman found bronze cannons and anchors in the waters off Morning Reef. The ship was found at a depth of 6 metres (19 ft), and the Museum of Western Australia was charged with protecting and managing the archaeological site. The find was significant for maritime archaeology.

Skeletal remains provided physical evidence of the brutal events that took place after the shipwreck. A wealth of artefacts was found, including compasses and hourglasses, clay pipes, 10,600 coins, glass bottles, cannonballs, an inkwell and fountain pen, as well as chess pieces. The ruins of Wiebbe Hayes' fort have also been located. In 2017, a communal grave holding the remains of five individuals was unearthed, along with more artefacts.

The wreck of the Batavia represents one of the earliest recorded European contacts with the Australian continent, pre-dating the British settlement at Botany Bay by nearly 170 years. It is a dark chapter in history, but the Batavia's fate also demonstrates the risks of early sea travel, the struggle for survival in new places, and how the established social order can break down in extreme situations.