The Philadelphia Campaign (July 1777 to June 1778) was a major military operation during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), in which a British army under Sir William Howe attempted to capture the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia and, in the process, draw the Continental Army into a decisive battle. Although the British captured Philadelphia, their campaign ultimately ended in failure.

Background: The Year of the Hangman

As the new year of 1777 dawned, Sir William Howe, commander-in-chief of the British army in North America, was pacing in his headquarters in New York City. The previous year, victory had been within his grasp; he had defeated the Americans at the Battle of Long Island (27 August 1776), captured New York City, and chased the ragged Continental Army out of Manhattan and through New Jersey. For these successes, Howe had been celebrated in London as a war hero and had even been knighted by the king. But the victory he sought had ultimately eluded him, partially due to his own caution and partially due to the wiliness of the American commander, General George Washington. In December 1776, Howe had decided to move his army into winter quarters rather than continue the pursuit of Washington's disease-ridden army; with less than 3,000 effectives, the Continental Army was not expected to survive the winter. However, the persistent Washington crossed the Delaware River during a storm on Christmas Day to win two surprise victories at the Battle of Trenton (26 December) and Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777), which galvanized support for the American Revolution and ensured the survival of the Continental Army.

Now, the Continental Army sat perched on the heights of Morristown, New Jersey, where every day it swelled with new recruits. But Howe was undeterred. His confidence was bolstered by the large number of Tories (or Loyalists) in New York City, who optimistically referred to 1777 as the 'Year of the Hangman' since the triple 7s appeared to resemble the gallows upon which the traitorous Patriots would soon hang. Never known for his hastiness, Howe was in no hurry to commence the next campaign season; he could often be found at high-end balls or plays, always in the company of his pretty American mistress, Mrs. Elizabeth Loring. Yet when he was not carousing with New York's high society, Howe was dreaming of Philadelphia. The city – which was not only the seat of the Second Continental Congress but also the largest city in the United States – lay not too far to the south of Howe's current position. He imagined that, by threatening the revolutionary capital, he could draw Washington's army out of hiding, and could fight the Americans on ground of his own choosing. If Howe could both destroy the Continental Army and capture Philadelphia in a single campaign season, he believed that the American rebellion would collapse. By the end of the year, the Patriots would indeed be swinging from gallows and the crowds in London would be cheering the name of Howe.

In February, Howe wrote about this plan to Lord George Germain, the colonial secretary of state. Germain sent a reply in which he outlined a different strategy that the British ministry had prepared for 1777: General John Burgoyne was going to lead an army out of Canada and march south along the Hudson River, thereby isolating the New England colonies and cutting the United States in half. Germain asked if Howe would be able to march north from New York City and join forces with Burgoyne at Albany. The British commander-in-chief was a little frustrated by this request; he did not want to support a campaign that would see most of the glory fall to his rival, Burgoyne, nor did he want to give up his golden opportunity to capture Philadelphia. Howe wrote back to Germain, emphasizing the importance of seizing Philadelphia now and promising that he would march in support of Burgoyne once the American capital had fallen. Germain acquiesced and gave Howe the go-ahead, although he failed to furnish Howe with the reinforcements and supplies that he had requested. Exasperated, Howe nevertheless began to prepare for the Philadelphia expedition, which he believed would win him the war.

The Expedition Begins

The Continental Army, meanwhile, remained at Morristown, where it watched British movements with bemusement. Many British vessels had entered New York Harbor, and it appeared the army was readying to embark: could the British be preparing to evacuate New York City? No – that would be too good to be true. They must be planning to attack somewhere else. But where? To find out, Washington moved his army out of Morristown and occupied the high ground of Middlebrook, New Jersey, which would offer him a better look at the British movements. Howe noticed this change in position and interpreted it as a sign that Washington was getting restless. On 13 July 1777, hoping to get in Washington's head, Howe moved 18,000 soldiers into New Jersey and had them march, with fifes and drums blaring, in the direction of the Delaware River, to imitate a march on Philadelphia. Washington refused to take the bait – his scouts had reported that the British had not taken their baggage, meaning they could not be planning to march all the way to Philadelphia. When Washington showed no sign of stirring, the British turned around and marched back to Manhattan – only to board the ships in the harbor and sail off into the Atlantic on 24 July.

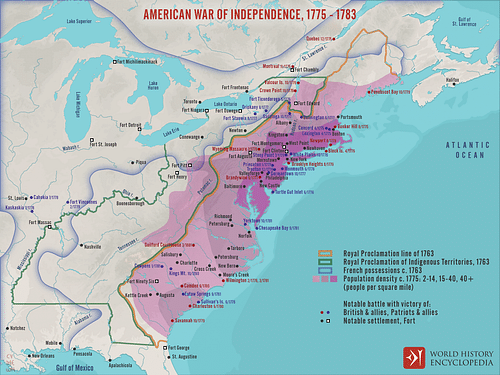

Howe had decided to go by sea rather than march to Philadelphia overland; the land route would require the British to pass by the Delaware River, which was heavily fortified by the Patriots, with Fort Mercer and Fort Mifflin guarding the river's mouth. After a grueling month at sea, the British fleet entered Chesapeake Bay, and the soldiers were disembarked on 25 August, at Head of Elk, Maryland. After resting for a few days to get over their seasickness, the British army then marched into Pennsylvania, only to find General Washington waiting for them at a stream called Brandywine Creek with around 16,000 Continentals and militia. The Americans enjoyed a strong defensive position, covering most of the major fords over the Brandywine; however, there were two fords far beyond the American right flank that had been overlooked. Joseph Galloway, a prominent Loyalist from Philadelphia, told Howe about those fords and offered to supply him with guides. So, on 11 September 1777, Howe ordered 5,000 men under German General Wilhelm von Knyphausen to assault the American center while 9,000 British and German troops followed the Tory guides around the American right flank.

The British caught the Americans by surprise, and Washington was only barely able to rush in enough troops to prevent his right flank from collapsing. By late afternoon, Knyphausen had smashed through the American center, and the right was close to falling, forcing Washington to order a retreat toward Chester, a town on the Delaware River some 14 miles (22 km) away. While a brigade under General Nathanael Greene held back the British onslaught, the rest of the army slipped away, aided by the onset of darkness. By sunrise on 12 September, the Americans had reached the safety of Chester. Although Howe had won the Battle of Brandywine, he had failed to achieve a decisive victory by destroying the Continental Army. Setting aside his frustrations, he continued his push toward Philadelphia.

Philadelphia Falls

Washington was still reluctant to allow Philadelphia to fall without a fight and, over the course of the next week, he tried to block Howe from entering the city while, at the same time, avoiding another major battle that could spell disaster for his army. A moment of crisis was almost reached when, on 16 September, the British caught up with the Americans at Warren Tavern, between Lancaster and Philadelphia. Both sides were preparing for battle when a torrential storm broke out, soaking gunpowder and cartridges and rendering a battle impossible (this event was later referred to as the Battle of the Clouds). Using the cover of the storm, Washington once again slipped away from Howe's grasp and retreated beyond the Schuylkill River on 19 September. However, while most of the army crossed, Washington left behind a division of 1,500 men under General Anthony Wayne to watch the British and, if possible, harass their rear.

As Howe prepared to march in pursuit of Washington, Wayne remained encamped at Paoli Tavern, only 2 miles (3 km) from the British camp. Wayne was confident that his small force was undetected by the British, but he was gravely mistaken. Late at night on 20 September, a detachment of 1,200 British soldiers under Major General Charles Grey silently approached Wayne's camp; to maintain the element of surprise, Grey ordered that they remove the flints from their muskets and rely only on the bayonet. When Grey gave the signal, the British rushed into the American camp, bayoneting the groggy American troops as they stumbled out from their tents. Wayne managed to form his men up to fire a volley at the British troops, but the Americans were quickly overwhelmed and were sent running into the dark woods. As many as 200 Americans were killed or wounded in the attack, with another 100 taken prisoner. The Battle of Paoli was referred to as a massacre by the Americans.

Washington was greatly disturbed when he learned about Paoli, leading him to become even more cautious than usual. Howe, deciding to take advantage of Washington's timidity, struck north on 22 September, giving the impression that he meant to swing around and strike Washington's flank. The Continental Army marched 10 miles (16 km) north to better position itself, at which point Howe swiftly swung back around and marched into Philadelphia unopposed. On 26 September 1777, Lord Charles Cornwallis led the vanguard of the British army into Philadelphia. To the British chagrin, Congress had already evacuated the city, having taken up temporary residence in the town of York, Pennsylvania.

Securing the Delaware

While Howe had achieved one of his major objectives, he felt far from secure; Washington's army lingered just out of sight at Skippack Creek, some 25 miles (40 km) away, while the Patriots still controlled access to the vital Delaware River, meaning that Howe could not easily ship supplies to Philadelphia by water. To avoid seeing his entire army become trapped in Philadelphia itself, Howe decided to spread out; keeping only 3,000 men in the city, he sent the bulk of his army, 9,000 men, to garrison nearby Germantown. Washington saw an opportunity to catch the British off guard; after marching the 23 miles to Germantown during a single night, the Americans attacked early on the morning of 4 October.

The assault initially got off to a great start, as the British pickets were taken totally by surprise and were driven back. But as the Americans pushed on toward the enemy camp, they soon became disorientated by a thick fog. Communication between the American units broke down, and two American brigades even fired at one another by accident. This confusion gave the British precious time to gather and launch a counterattack, which was enough to break the Americans. By the end of the day, the Continental Army was once again on the retreat, but the soldiers remained in high spirits, believing (falsely) that they had come close to beating the British.

After the Battle of Germantown, Howe sought to tighten his grip over Philadelphia by securing control of the Delaware River. The river was defended by two Patriot forts; Fort Mifflin was located on an island in the middle of the river while Fort Mercer was located on the east bank. The forts were supported by a flotilla of Pennsylvania ships under Commodore John Hazelwood. In early October, Howe sent detachments of troops to capture the forts, supported by a squadron of Royal Navy ships commanded by his elder brother, Admiral Lord Richard Howe. On 11 October, Admiral Howe bombarded Fort Mifflin by sea while on 22 October, a detachment of 1,200 Germans under Colonel Carl von Donop assaulted Fort Mercer. Fort Mercer was defended by 400 Patriot troops under Colonel Christopher Greene, including the noteworthy 1st Rhode Island Regiment (famous for being the first majority-Black regiment in the American military). The German assault, known as the Battle of Red Bank, ended in failure; over 300 Germans were killed, wounded, or captured, including Donop, who was mortally wounded.

Despite the setback at Red Bank, the British continued to put pressure on the two forts. On 10 November, Admiral Howe unleashed a full-scale bombardment on Fort Mifflin, resulting in the fort's surrender five days later. On 20 November, Lord Cornwallis landed three miles to the south of Fort Mercer with 2,000 men; rather than risk the lives of his men, Colonel Greene decided to abandon the fort, which the British occupied the next day. By the end of November, therefore, General Howe controlled access to the Delaware River, which was critical to keep his army in Philadelphia supplied for the winter.

Winter Sets In

Between 5 and 8 December, the British and Patriot forces engaged in a series of skirmishes known collectively as the Battle of White Marsh. After this inconclusive fight, both armies settled into winter quarters: the British in Philadelphia, and the Continental Army at Valley Forge, about 20 miles (32 km) away. By this point, Howe had become quite frustrated; although he had succeeded in capturing Philadelphia, he had failed to capture Congress or destroy the Continental Army. The fall of the revolutionary capital did not have the demoralizing effect on the American public that Howe had counted on, meaning that the war was no closer to being over; indeed, the surrender of Howe's counterpart, Burgoyne, at the Battles of Saratoga only seemed to further electrify the Patriot movement (without Howe's support, Burgoyne's campaign had fallen apart). Howe blamed his failure to secure a more complete victory on the British ministry, accusing them of inadequately supporting his campaign. In late October, Howe submitted his resignation. He spent the winter carousing in Philadelphia with his mistress Mrs. Loring until April 1778, when he received word that his resignation had been accepted. His officers were sorry to see him go and threw him an extravagant fête, called the Mischianza, to mark his departure on 18 May 1778.

Meanwhile, at Valley Forge, the Continental Army was suffering. Many soldiers went without shoes or coats, and were forced to subsist on meager rations; ultimately, exposure, starvation, and disease would kill up to 2,500 soldiers at Valley Forge. Washington worked tirelessly to remedy this situation. He reorganized the army's supply department, installing his favorite subordinate Nathanael Greene as quartermaster general. He sent out patrols to scour the countryside for provisions and ordered every soldier who was not yet inoculated against smallpox to do so. He even fended off the so-called Conway Cabal, a loose attempt by disenfranchised military officers and members of Congress to remove him from command. But by far the most important accomplishment to come out of Valley Forge was the retraining of the Continental Army. Under the supervision of the Prussian officer Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, the Continental soldiers were incessantly drilled, taught new formation and battle techniques, and practiced standardized marching. The Continental Army that emerged from Valley Forge was, therefore, a much more disciplined and effective fighting force.

The British Evacuate

In February 1778, the United States signed a Treaty of Alliance with the Kingdom of France. Shortly thereafter, a French fleet was spotted leaving the port of Toulon and sailing for the Americas. Alarmed, the British ministry realized it had to adopt a more defensive strategy – Sir Henry Clinton, Howe's replacement, was ordered to evacuate Philadelphia and march to the defense of New York City, which was deemed more valuable to the British war effort. On 15 June 1778, Clinton began an overland retreat, with the last British troops crossing the Delaware into New Jersey three days later. Washington pursued, eager to restore his martial reputation after the defeats of the previous year. On 28 June, the Americans attacked the British at the Battle of Monmouth. Washington's second-in-command, General Charles Lee, commanded the American vanguard but ordered a premature retreat, giving Clinton time to rally his forces. Washington arrived on the scene and was able to get his men in a good enough position to withstand a British counterattack. The battle ended inconclusively, although the discipline displayed by the Continental soldiers proved that their Valley Forge training had paid off.

By July, Clinton's army was back in New York City, with Washington making his own headquarters at White Plains, New York. Both armies were roughly in the same position that they had been two years earlier, in October 1776. Since Philadelphia had fallen back into Patriot hands, Howe's grand Philadelphia Campaign had failed to achieve any lasting success. Due to the failures of both the Philadelphia Campaign and Burgoyne's concurrent Saratoga Campaign (June to October 1777), the British ministry decided to turn its attention away from the north and toward the American South; rumored to be replete with Tories, the south seemed to offer a better chance at a lasting British victory. The next major British offensive would not occur until 1780, when Clinton's Siege of Charleston (29 March to 21 May 1780) sparked the British invasion of the Carolinas. This southern campaign, culminating in the British surrender at the Siege of Yorktown, would mark the final phase of the war.