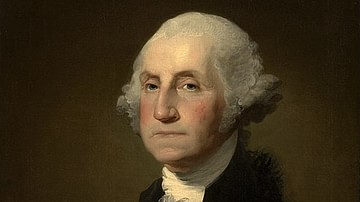

The Battle of Monmouth (28 June 1778), or the Battle of Monmouth Court House, was the last battle of the Philadelphia Campaign during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). After abandoning control of Philadelphia, the British army under Sir Henry Clinton was attacked by the Continental Army under General George Washington, recently retrained at Valley Forge. The battle was tactically inconclusive.

The campaign, which had begun the previous year, initially went disastrously for the Americans. The British had dealt Washington two defeats, first at the Battle of Brandywine (11 September 1777), then at the Battle of Germantown (4 October 1777), and had gone on to capture the American revolutionary capital of Philadelphia. The campaign reached a stalemate in December, as both armies settled into winter quarters, with the British in Philadelphia and the Americans at Valley Forge, about 20 miles (32 km) away. General Washington spent the winter rebuilding and retraining his army, which would emerge the following spring as a more effective and disciplined fighting force.

The entry of France into the war as an American ally forced the British army to abandon Philadelphia, in order to consolidate their forces elsewhere. As the British crossed over the Delaware River into New Jersey, they were pursued by Washington, who hoped to restore his reputation after the defeats of the previous year. On 28 June 1778, the British rearguard was attacked by an American detachment under General Charles Lee, Washington's second-in-command, at Monmouth Court House (modern Freehold Borough, New Jersey). Lee botched his attack, however, and ordered a premature retreat, giving the British a chance to counterattack. Fortunately for the Americans, Washington arrived with the main army and took up a strong defensive position, forcing the British to break off their attack. Although the battle ended inconclusively, with neither side gaining much of an advantage, the Continental Army remained steady under fire and retained control of the battlefield, attesting to the effectiveness of its Valley Forge training.

Clinton Abandons Philadelphia

In February 1778, a Treaty of Alliance was signed between the United States and the Kingdom of France. A month later, the French formally declared war on Great Britain, and a French fleet sailed out of the port of Toulon and headed toward the Americas. Alarmed, the British ministry was forced to abandon its offensive war plans and adopt a more defensive strategy; the British were primarily worried about their lucrative colonies in the West Indies, considered one of the more vulnerable targets at which the French might strike. In May 1778, Sir Henry Clinton, recently appointed commander-in-chief of the British army in North America, received orders to evacuate Philadelphia and retreat to British-occupied New York City. Once there, he was to redeploy 8,000 troops to the West Indies and Florida and remain in New York with the rest of the army to defend against a potential French attack. Clinton, who had always believed the Philadelphia expedition to have been an ill-conceived folly, was only too happy to comply and began preparing his army for the march.

On 15 June 1778, the British evacuation began. A small flotilla on the Delaware River was loaded with the army's heavy equipment, its sick or otherwise incapacitated troops, as well as 3,000 Philadelphian Loyalists and their families, who preferred to leave the city rather than see it fall back into Patriot hands. The army, roughly 17,500 strong, would take the overland route to New York, passing through New Jersey. For the journey, Clinton split his army into two divisions: the first, led by Lord Charles Cornwallis, consisted of 10,000 men, while the second 7,500-man division was commanded by German General Wilhelm von Knyphausen. They were trailed by a cumbersome, 1,500-wagon baggage train that included the personal possessions of the officers and men, as well as the laundries, bakeries, and hospital supplies needed to sustain the army. The British crossed over the Delaware River on flatbottom boats, a process that took three days, before commencing its march through New Jersey. The stifling summer heat, which rarely dipped below 90 °F (32 °C), caused many British and German troops to fall victim to heat stroke and slowed the army's progress to a crawl. It took the British army six days to cover the 35 miles (56 km) to Allentown, New Jersey, where it stopped to rest on 24 June.

The Continental Army, meanwhile, had been eyeing British movements from Valley Forge. Washington had long suspected that the British were planning to leave Philadelphia, and once these suspicions were confirmed on 17 June, he immediately held a war council. Washington himself favored an immediate attack. He was eager to test out his revitalized army after its months of Valley Forge training and, moreover, wished to recover his military reputation after the previous year's defeats. His generals, however, were not so willing to force a battle, arguing that even after all their training, the Continentals were not ready to face down British regulars.

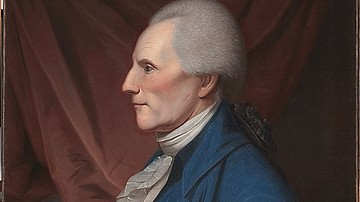

This opposition was led by Major General Charles Lee, who had recently rejoined the army after spending the previous year and a half as a British prisoner-of-war; Lee's reputation as an experienced and knowledgeable general caused most of Washington's less-experienced officers to side with him. Washington backed down, agreeing not to engage in a pitched battle, but could not resist at least pursuing the British army. On 18 June, the 13,500-man Continental Army left Valley Forge and, by 23 June, had reached Hopewell, New Jersey, less than 25 miles (40 km) from the British position at Allentown. The speed with which the Americans marched, especially compared to the slowness of the British, was a testament to the success of their training.

Another War Council

On 25 June, the British left Allentown and marched into Monmouth County, New Jersey. Monmouth County had long been the scene of a brutal civil war between Patriot and Loyalist guerilla fighters; all throughout the morning, General Knyphausen's division came under consistent fire from Patriot partisans, resulting in over 40 British casualties. When Knyphausen's division reached Monmouth Court House that afternoon, the enraged British troops vented their frustrations by ransacking and vandalizing nearby houses, with their officers turning a blind eye. The British decided to remain here for a few days to allow the rest of the army time to catch up. At their Monmouth encampment, the British were joined by several local Tory (Loyalist) militias including the formidable Queen's Rangers.

On 24 June at Hopewell, Washington convened another war council and posed the question once again: attack or desist? Washington again favored an assault, but he was again challenged by General Lee, who insisted they should wait to force a major engagement until the arrival of the French army, arguing that any attack prior to that would be 'criminal'. Lee claimed that it was a good thing that the British were going back to New York City where they could be contained, adding that he wished he could "build a bridge of gold" to help the British get there as swiftly as possible (Fleming, 86). The majority of Washington's generals were once again swayed by Lee's reputation and argued against a full attack; Lt. Colonel Alexander Hamilton, attending the meeting as Washington's aid, was disgusted by the generals' blind agreeance with Lee, later sneering that the council "would have done honor to the most honorable society of midwives, and to them only" (Chernow, 113).

Washington was still hesitant to let the British retreat to New York unscathed and proposed a compromise: a vanguard would be sent to harass the British rear and attack if an opportunity presented itself, but no pitched battle would be fought. The generals agreed, and it was decided that this vanguard would consist of 1,500 men. Command of the vanguard was initially offered to Lee, as the most senior of Washington's generals, Lee felt that even this was taking things too far and declined. Command was then given to the 20-year-old French general Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Once Lafayette accepted, the number of troops in the vanguard was increased to 4,500 men; upon hearing this, Lee changed his mind and demanded to be given command of the vanguard, believing that he would be dishonored if word spread that he had declined to lead such a large detachment. Exasperated, Washington agreed to let Lee lead the vanguard, and Lafayette graciously stepped aside.

Lee's Attack

On 27 June 1778, Lee led his vanguard to Englishtown, about 6 miles (10 km) from the British position at Monmouth Court House. Washington was with the main body of 7,800 men a further 4 miles (6 km) behind Lee, ready to march in support if necessary. Major General Philemon Dickinson had arrived with 1,200 New Jersey militia and was positioned along the British flank, ready to report to Washington once the enemy began to move. Whenever that moment came, Lee was supposed to strike at the British rearguard and cause as much damage as he could. But as the afternoon gave way to dusk, Lee had not yet informed the generals under his command – Lafayette, Anthony Wayne, and Charles Scott – about his battle plan. Indeed, it was not apparent whether he had one at all.

At 4 a.m. the next morning, the British began to move. Knyphausen's division started north in the direction of Middletown, New Jersey, while Cornwallis' division lingered in Monmouth Court House to protect the baggage train. General Dickinson immediately noted the movement and sent reports to both Washington and Lee, before moving his militia in to get a closer look. At around 8 a.m., Dickinson's men were moving through the swampy terrain of a gorge known as the West Ravine when they encountered the Queen's Rangers; this resulted in a bloody, all-American skirmish along the ravine that ended once the Tories withdrew. About an hour later, the bulk of Lee's detachment arrived at Dickinson's position. After conferring with the militia general, Lee surmised that most of the British army had already left Monmouth Court House, leaving behind a small rearguard of only 500 light infantry and dragoons.

Lee decided to attack, believing he could destroy the rearguard in a quick action. Penning a letter to Washington in which he expressed confidence in a victory, he ordered General Wayne to take 550 men and strike at the British center to hold it in place, while the rest of the vanguard circled around to attack the enemy rear. Wayne dutifully obeyed and engaged the British rearguard at the junction of the Middletown and Shrewsbury roads – only to find that it was actually comprised of 2,000 men, much larger than expected. As Wayne's men exchanged fire with the British, it slowly lost ground. Meanwhile, Lee arrived in position with the rest of the vanguard only to discover that another detachment of 3,000 redcoats had turned around and was marching to support the rearguard. Lafayette's troops, on the right of Lee's line, began to waver and pull back; realizing he was quickly losing control of the situation, and with communication breaking down, Lee ordered a retreat. By 10 a.m., Lee's vanguard was fleeing back down the road to Englishtown, with the bulk of Cornwallis' 10,000-man division in close pursuit.

Washington Arrives

As soon as he had learned that Lee was committing to an attack, Washington had begun to march toward Monmouth Court House in support. But as he came within a few miles of the town, Washington became disturbed; where he had expected to hear the thunderous sound of battle, he was instead greeted by an ominous silence. Soon enough, hundreds of fleeing Continental soldiers started to stream past him, and it became apparent that Lee's attack had failed. Around 12:45 p.m., General Lee himself finally came riding into sight. Unable to contain his rage, the usually even-tempered Washington bore down upon his second-in-command, demanding to know what had happened. Lee, startled by his commander's fury, was at first only able to stammer, "Sir? Sir?" He then rattled off a series of excuses – his generals had disobeyed his orders, communication had broken down, he had not wanted to fight any battle in the first place. "All this may be true, sir," shouted Washington, "but you ought not to have undertaken [the attack] unless you intended to go through with it!" (Fleming, 90). The American commander-in-chief then unleashed such a tirade that, according to General Charles Scott, "the leaves shook from the trees" (ibid).

Washington's outburst was only contained when a courier arrived, breathlessly reporting that the British were only 15 minutes away. With no time to lose, Washington sprang into action. Aided by an officer, Colonel David Rhea, who was familiar with the area, Washington decided to establish a line of defense at Perrine Ridge, the high ground just behind the West Ravine. Sending several battalions ahead into a 'Point of the Woods' to delay the British advance, Washington placed General Nathanael Greene's division on the right side of the Perrine Heights, with General William Alexander 'Lord Stirling' in command on the left; both flanks were supported by artillery. General Anthony Wayne was given command of five regiments from Lee's vanguard and positioned just ahead of the American center, concealed in the trees.

British Counterattack

The Americans barely had time to get into position before Cornwallis' British troops marched into view. After a brief skirmish, the British swept away the forward American battalions at the 'Point of the Woods', although the Americans had held out long enough for the main army to form up on Perrine Heights. As the British drew closer to the ridge, Brigadier General Henry Knox ordered the Continental artillery to open fire; the British cannons responded, beginning a thunderous artillery duel that lasted throughout the day. General Clinton, riding back and forth atop his horse, urged his men onward, and ordered a charge against the American left flank.

A swarm of British infantry, including the dreaded 42nd Royal Highland 'Black Watch' Regiment, charged forward and slammed into Lord Stirling's division. For the next hour, the British attempted to break through or envelop Stirling's line, but the American military discipline instilled at Valley Forge paid off. Musket volleys were exchanged, filling the air with acrid white smoke, and bayonets flashed in the sun as the British charged again and again, but still, the Continentals held their ground. Eventually, a countercharge made by a New Hampshire and a Virginia regiment drove the British back, ending the threat to Stirling's flank. Clinton next ordered an attack against the American right flank; led by Lord Cornwallis in person, this attack consisted of the elite Coldstream Guards, as well as battalions of British and Hessian grenadiers. But General Greene's flank, too, stood its ground, his cannons perched atop nearby Comb's Hill shredding into the British flank with enfilading fire. Before long, this British attack had also disintegrated.

Slightly ahead of the American center, Wayne's troops remained hidden in the woods, until a detachment of British light infantry and grenadiers marched by, on their way to join the assault against Greene. Wayne waited for them to pass close by before ordering his men to fire; at such close range, around 40 redcoats fell to the ground. The British tried twice to dislodge Wayne from his position, but each time they were repulsed with devastating losses. After the failure of the second charge, the British were rallied by Lt. Colonel Henry Monckton, who urged them onward with the words, "Forward to the charge, my brave grenadiers!" (Boatner, 724). But Monckton's charge met with the same fate as the first two attempts; the 'brave grenadiers' were cut to pieces by Wayne's muskets and Stirling's cannons. Monckton himself fell mortally wounded, his body captured by the Americans as his dispirited men fled into the woods.

At 5 p.m., General Clinton called off any further infantry attacks, although the British and American cannons continued to trade fire until dusk. It had been a brutal battle, fought in a stifling heat that approached 100°F (38°C); a not-insignificant portion of the casualties had been caused by heat exhaustion. After nightfall, the Americans maintained their positions, expecting the British to renew the attack the following morning. However, when the sun rose on 29 June, they found that the British army had slipped away in the night; Clinton saw no value in continuing to attack the strong American position, preferring to continue his march to New York. The Battle of Monmouth was over. According to official estimates, the Americans lost 356 casualties while the British suffered 358 losses. However, some estimates place the losses of both armies significantly higher, placing American casualties at 500 and for the British as high as 1,200.

Aftermath

Clinton reached the safety of New York in early July, with Washington taking up a position at White Plains, New York, ending the campaign. Lee, who was instantly lambasted for his failings at Monmouth, demanded a court-martial to clear his name. He got the court-martial he desired but was found guilty of disobeying orders, conducting an 'unnecessary' retreat, and of disrespecting the commander-in-chief. He was suspended from the army for a year and never held a significant command again. The Battle of Monmouth, though tactically inconclusive, was touted as a victory for the Continental Army, which had proven that it had benefited from the training at Valley Forge and that it could indeed stand up to British regulars.