The Battle of Rhode Island (29 August 1778), also known as the Siege of Newport or the Battle of Quaker Hill, was fought during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). It marked the first attempt at cooperation between the American and French militaries, although plans for a joint attack unraveled after the French fleet was damaged in a storm.

In August 1778, a French fleet under Comte d'Estaing sailed into Rhode Island's Narragansett Bay. Its goal was to assault the British-occupied town of Newport from the west while a 10,000-man American army under General John Sullivan attacked from the east. But before this plan could be put into action, the French ships were lured away from Newport in pursuit of a British fleet; a sudden storm then damaged the French fleet, which was forced to sail to Boston to seek repairs. Abandoned by his French allies, Sullivan was about to lift the siege of Newport when he was attacked by the town's garrison of British troops under Sir Robert Pigot. The Americans held their ground and beat back the British attack; the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, an American military unit comprised mainly of Black soldiers, repulsed three separate Hessian assaults. After the battle, Sullivan's army resumed its evacuation, leaving Newport in British hands. The Franco-American alliance, though off to a bad start, would persist, ultimately leading to success at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781).

Arrival of the French

In February 1778, the Kingdom of France signed a Treaty of Alliance with the United States of America and shortly thereafter declared war on Great Britain. France was eager to help weaken Britain's colonial empire and had been convinced to join the conflict by the impressive American victory at the Battles of Saratoga the previous year. On 13 April 1778, a French fleet of 12 ships of the line set sail from the port of Toulon on the Mediterranean coast. It was commanded by Charles Henri Hector, Comte d'Estaing, who had been put in charge of the fleet even though he was primarily a soldier and had limited naval experience. D'Estaing sailed for the Americas; while he was under orders to cooperate with the Americans, his primary objective was to seize Britain's lucrative colonial possessions in the West Indies.

The British had noted the departure of d'Estaing's fleet from Toulon. When the French fleet cleared the Strait of Gibraltar on 16 May, the British were under no illusions that it was headed for the Americas. Alarmed, the British ministry dispatched fresh orders to Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British army in North America: Clinton was to send a third of his army, or 8,000 men, to defend British interests in the West Indies, while the remainder of his force concentrated in New York City, deemed one of the most likely targets of the French. The British also decided to send Admiral John 'Foul-Weather Jack' Byron with 13 ships of the line to follow the French fleet to North America. However, a few days into its voyage, Byron's fleet was scattered by a sudden gale and would not reach North American waters until early August.

By early July, Clinton succeeded in withdrawing the bulk of his army into New York City, while the British North American fleet, under Admiral Lord Richard Howe, made anchor at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, off the southern entrance to New York Harbor. On 11 July, d'Estaing's ships arrived off Sandy Hook but hesitated to attack the British fleet that was sheltering in the bay. D'Estaing outnumbered Howe, but he was nervous that his largest ships would be unable to clear the bar at the mouth of the harbor and would become stuck. For this reason, the French admiral postponed the attack as he searched for a local American pilot to guide his ships past the bar. Each pilot he encountered refused to help, no matter how much money d'Estaing offered. On 19 July, the British managed to establish an artillery battery on Sandy Hook, which could inflict heavy damage on the French ships if they tried to enter the harbor. D'Estaing had, therefore, lost his chance to corner and destroy Howe's fleet.

The Franco-American Expedition

As the French remained anchored off Sandy Hook, they were greeted by Colonel John Laurens, a young aide-de-camp to General George Washington. Laurens boarded the French flagship, Languedoc, welcoming d'Estaing on behalf of the Continental Army and suggesting that they plan a joint Franco-American attack against the British army in New York City. D'Estaing received the American officer warmly but declined to participate in an assault against New York as he deemed it too dangerous to attempt an entry into the harbor and feared that, if he lingered off Sandy Hook for too long, he would become trapped between two British fleets once Byron finally arrived. Slightly disappointed, Laurens offered an alternative target: Newport, Rhode Island. Situated on Aquidneck Island, Newport was a bustling port town that had been captured by the British on 8 December 1776. It was now garrisoned by 6,000 British soldiers under Sir Robert Pigot, a force that could easily be overwhelmed by a combined Franco-American army. D'Estaing agreed, and on 22 July, Laurens returned to the Continental Army to inform Washington of the change of plans, while the French fleet raised anchor and sailed for Rhode Island.

Washington quickly notified Major General John Sullivan about the impending attack. Sullivan, who was encamped at Providence, Rhode Island, with 1,600 Continental soldiers, was put in charge of the American half of the expedition and was ordered to raise as many men as he could. Sullivan immediately called on the New England militias, and by the first week of August, his army was bursting with thousands of militiamen, who were eager to chase the British off New English soil once and for all. The militias were personally led by John Hancock, former president of the Second Continental Congress, while another revolutionary hero, Colonel Paul Revere, commanded an artillery regiment. Alongside these militia forces, Sullivan was joined by two brigades of Continental soldiers, under generals James Varnum and John Glover, which had been sent by Washington to join the attack. Also sent by Washington were generals Nathanael Greene and Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, who were to act as the commander-in-chief's eyes and ears in Rhode Island. Although Sullivan was unquestionably loyal, his recklessness had resulted in costly mistakes during previous battles, leading Washington to dispatch Greene and Lafayette to act as a counterbalance to Sullivan's impulsivity. In all, Sullivan's army numbered some 10,000 men, the vast majority of whom were militia.

On 30 July, d'Estaing's fleet sailed into Rhode Island's Narragansett Bay; four days later, he landed several French troops on the island of Coanicut, just to the west of Newport. General Sullivan was then invited onto the French flagship so that the allied commanders could plan the attack, but it did not take long for relations to break down. The French officers, dressed in their smart white uniforms, scoffed at the comparatively ragged look of the American soldiers, whose uniforms were mismatched and filthy. The French also openly derided the Americans' military ability, particularly mocking their reliance on militias, causing friction between the allied groups. Another point of contention occurred when Sullivan, the provincially mannered son of Irish immigrants, attempted to give orders to d'Estaing, a well-bred French aristocrat from an ancient family. D'Estaing became incensed by Sullivan's behavior, angrily refusing to take orders from any American; tensions were only calmed by the efforts of Lafayette, who was acting as translator.

In the end, the American and French leaders were able to put aside their differences long enough to formulate a battle plan. Sullivan was to march his army down from Providence, cross over onto Aquidneck Island, and then assault Newport from its eastern side. D'Estaing would simultaneously disembark his 4,000 French marines and assault the city from the western side. The plan was slated to go into effect on 10 August, and the allied commanders parted ways, neither side much impressed with the other.

Naval Action

With the arrival of the French fleet in Narragansett Bay, the British scrambled to mount a defense. Sir Robert Pigot, commander of the Newport garrison, sent five frigates into the middle passage between Conanicut island and Newport Harbor, to act as a buffer between the city and the French. Each of the frigates, however, ran aground and was burnt by its crew. Pigot next ordered several transports to be sunk in Newport harbor, as a makeshift barrier against the enemy ships. He wrote to British headquarters in New York City to request reinforcements, leading General Clinton to dispatch an additional 6,000 troops to aid Newport's defense. Admiral Howe, meanwhile, had guessed d'Estaing's destination and had already set sail for Rhode Island to catch him.

On 9 August, Pigot pulled his men back from their outer defenses on Aquidneck Island, consolidating them within the boundaries of Newport itself. Sullivan immediately moved his army onto the island, a day earlier than initially planned; the opportunity to occupy the island and keep the British contained in Newport seemed too good to pass up. D'Estaing, however, viewed this premature move as an example of American unreliability. That afternoon, French lookouts spotted the sails of British ships on the horizon; Admiral Howe had arrived with 20 warships, having been reinforced by several ships from Byron's fleet. Outnumbered and outgunned, the French nevertheless had the advantage of a favorable wind. Much like Sullivan, d'Estaing, too, decided to take advantage of a sudden opportunity. Promising the Americans that he would return to aid in the assault on Newport, he sailed away to deal with the British fleet.

Admiral Howe was unwilling to fight a battle against the wind and began sailing back south. D'Estaing pursued and was slowly lured further away from Rhode Island. This pursuit lasted for two full days until, on 12 August, the fleets finally began forming up for battle. The roar of the ships' cannons was soon matched, however, by the roar of thunder, as a mighty storm quickly descended on the two fleets. The storm lasted for 48 hours, scattering the ships, and inflicting much damage. When it was over, the British fleet sailed back to New York Harbor to seek repairs while the French ships rallied at Narragansett Bay to assess the damage. The French had undoubtedly taken the brunt of the storm. Several ships had been dismasted including the flagship, Languedoc, which had lost all three masts and suffered a snapped rudder.

D'Estaing knew his fleet was in no condition to fight and, on 20 August, announced that he was going to sail for Boston, the nearest town with a large enough port for the necessary repairs. Sullivan pleaded with the French admiral to stay for 48 hours to complete the assault, but d'Estaing refused; still fearful that the rest of Byron's ships would appear on the horizon, the French admiral sailed away at midnight on 21 August. When he heard the news, Sullivan launched into a frenzied tirade that was so anti-French that Lafayette nearly challenged him to a duel. Upon calming down, Sullivan sent Lafayette to Boston to see if d'Estaing could not be persuaded to return by his own countryman. It was to no avail; Lafayette returned bearing d'Estaing's stubborn refusal. Sullivan's army was on its own.

The British Attack

Initially, Sullivan had planned to continue laying siege to the British army in Newport. But shortly after the French departure, Sullivan learned about the 6,000 British soldiers sent by Clinton to aid the Newport garrison; the arrival of these troops could potentially trap Sullivan's army on Aquidneck Island. This revelation alarmed the New England militiamen, who began deserting the army by the hundreds; within a week of d'Estaing's parting, the American army at Newport was reduced to barely 5,000 men. Sullivan was, therefore, forced to reconsider his options. "To evacuate the island is death," he wrote to General Greene in explanation of his dilemma, "but to stay may be ruin" (Boatner, 792). On the morning of 28 August, Sullivan made up his mind and began preparing to evacuate the island. To cover the evacuation of the main army, Sullivan organized a defensive line: General Nathanael Greene guarded the American right flank, positioned in front of Turkey Hill while General John Glover's brigade was positioned at a stone wall behind Quaker Hill.

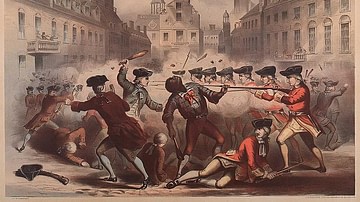

Pigot, meanwhile, had learned about the American evacuation plans from deserters and resolved to not let the American retreat go unscathed. Early on the morning of 29 August, he sent two detachments to attack Sullivan's troops: the first detachment, under General Francis Smith, would advance up the east road to attack the American left flank while the second detachment under Hessian General Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg moved up the west road against the American right. At around 7:30 in the morning, Smith's column of redcoats came under fire from Continental troops led by Colonel Henry Brockholst Livingston who were positioned at a windmill near Quaker Hill. After several minutes of bloody skirmishing, General Smith found that he was unable to dislodge the Americans from their position and requested reinforcements. Once two more British regiments arrived, Smith attempted another attack; this time, he managed to drive Livingston's men over Quaker Hill. Smith's victorious British troops then crested the hill, eager to pursue – only to find Glover's entire brigade awaiting them behind a stone wall. Smith ordered an assault that was quickly repulsed; instead of trying again, Smith opted to remain on Quaker Hill.

Similarly, on the right flank, General Lossberg's Hessians succeeded in driving the Americans off Turkey Hill, only to be confronted by General Greene's brigade. Lossberg continued to consolidate his position atop Turkey Hill, waiting until 10 a.m., at which point several British ships opened fire on Greene's position from the bay. Lossberg then hurled his men at the American lines. The 1st Rhode Island Regiment received the brunt of this attack but held its ground, fending off three separate Hessian assaults; the 1st Rhode Island was notable for being the first American military unit to be comprised of primarily Black soldiers, who were reported to have shown "desperate valor" during the battle (Boatner, 792). At 2 p.m., Lossberg made another attack, but his men were again driven back by American musket and artillery fire. Sensing a weakness in the enemy line, Greene ordered a counterattack, which pushed Lossberg's Germans back to the top of Turkey Hill. When night fell, the British and Germans controlled the two hills but had been unable to break through the American lines. American losses during the day had been 30 killed, 137 wounded, and 44 missing out of the 1,500 who were engaged. The British had lost 38 killed, 210 wounded, and 12 missing, the majority of whom were German troops.

Aftermath

The British did not attack again the next day; Pigot expected the arrival of Clinton's reinforcements any moment and did not want to assault before their arrival. He waited too long, however, as Sullivan's army successfully evacuated Aquidneck Island during the night of 30-31 August, leaving the island under British control. Clinton finally arrived with the reinforcements on 1 September but, seeing the threat was over, decided to raid several Massachusetts coastal towns before withdrawing back to New York. The British would retain control of Newport for another year, before finally abandoning it in October 1779 in order to concentrate their troops in New York and prepare for the Siege of Charleston.

After the battle, Sullivan continued to lambast d'Estaing's conduct, blaming the French for the failure to take Newport. Lafayette continued to defend his countrymen, writing to Washington that Sullivan's behavior had put him "more upon a warlike footing in the American lines than when I came near the British lines at Newport" (Boatner, 793). The French, meanwhile, were not making any friends at Boston, where memories of the French and Indian War (1754-1763) still lingered, causing many New Englanders to distrust the French. Indeed, on 5 September, a mob of Bostonians ransacked a bakery established by the French sailors in the town. When a young French officer, Chevalier de Saint Sauveur, attempted to stop the riot, he was shot dead by the frenzied mob. Horrified by this news, the Massachusetts House of Delegates tried to smooth things over by erecting a monument in Saint Sauveur's honor. D'Estaing, however, had had enough of American hospitality and set sail for the West Indies. He would return to North America in time to participate in the ill-fated Siege of Savannah in 1779.

The Battle of Rhode Island was not a promising start to the Franco-American alliance. However, it did showcase the discipline and training that the Continental soldiers had recently learned during their winter at Valley Forge. The Americans had held their ground for an entire day against British attacks and had evacuated the island in an orderly manner. Additionally, the valor displayed by the Black soldiers of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment impressed the American commanding officers, leading Congress to allow more Black troops to enlist in the Continental Army the following year. In conclusion, while the Battle of Rhode Island did not accomplish much strategically, it remains significant for being the first attempt at cooperation between American and French militaries and as a steppingstone for the transformation of the Continental Army into an effective fighting force.