The Siege of Savannah (16 September to 20 October 1779) was a significant engagement in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Hoping to retake Savannah, Georgia, which had fallen to the British the previous year, a Franco-American force laid siege to the city. Their efforts culminated in a failed assault on 9 October, after which the allies abandoned the siege.

Background: The British Change Strategies

For the first three years of the war, Britain’s military strategy had focused on the northern United States. The British had believed that the New England colonies and Middle Colonies were the heart of the American rebellion and thought they could end the war by suppressing them. However, the campaigns of the last several years had been less than satisfactory; no matter what gains the British armies made, they had always come up short of decisively defeating General George Washington and the Continental Army. This was partly because of Washington’s own wiliness and reluctance to fight a risky battle. But it was also because the north was a bastion of Patriotism (with some notable exceptions, such as New York City, which was one of the strongest Loyalist strongholds in the country). Whenever it was in danger of destruction, Washington’s army would always find support from nearby Patriot governments and was frequently bolstered by fresh recruits and state militias. As long as the Continental Army survived, the war would continue, and as long as the Patriot movement remained strong in the north, the Continental Army would survive.

So, the British were forced to adopt a new strategy, and decided to shift their focus to the American South. This was done for several reasons. The first was that the south had long been rumored to be as Loyalist as the north was Patriotic; the British believed that, if they could only land an army on southern shores, then southern Loyalists would revolt en masse, proclaim their allegiance to the king, and help topple their revolutionary governments. An additional incentive was that most of the United States’ cash crops were cultivated in the south, such as indigo, rice, and tobacco. The profits from the sale of these crops were being used by the Americans to purchase war supplies. If the British could occupy the southern states, therefore, they could remove one of the major sources of US revenue, thereby disrupting the American economy and crippling its war effort. The fall of the south, it was believed, would lead to the suppression of the north and an end to the long and bitter war.

Capture of Savannah: December 1778

With this strategy in mind, Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British army in North America, decided to dispatch an expeditionary force to the state of Georgia, to probe the situation there before launching a larger invasion. On 27 November 1778, a small, 3,500-man British force under Lt. Colonel Archibald Campbell, departed from New York. Escorted by a squadron of warships, the British force sailed along the coastline, finally landing on Tybee Island near the mouth of the Savannah River on 23 December. The British landing was noticed by the town of Savannah, which alerted the Southern Department of the Continental Army, led by Major General Robert Howe (no relation to the prominent British military family also named Howe).

Howe, who was 30 miles away at Sunbury, rushed to Savannah with an army of 700 Continentals (or regulars) and 150 militia. He arrived on Christmas Day and was dismayed to find that Savannah’s old fortifications had fallen into a state of disrepair. General Howe decided not to risk relying on these fortifications, and instead set up his main line of defense half a mile southeast of the town, covering the main road that led from the British landing site. It was a strong position; Howe’s army was flanked on one side by the Savannah River as well as by several rice swamps, and on the other by wooded marshes. Feeling secure, Howe decided to hold this position, even though he was outnumbered four to one and most of his soldiers had not yet seen a battle.

Campbell, meanwhile, had landed at Girardeau’s Plantation on the mainland and had begun his march toward Savannah. At around 2 pm on 29 December, the British vanguard spotted the American position and reported back to Campbell, who ordered his army to halt while he assessed the enemy formations. As he reconnoitered the enemy line, Campbell was approached by an enslaved man named Quamino Dolly, who offered to show the British a path through the swamps and around the American line (the British had offered freedom to all southern slaves who aided them, causing many to flock to the Loyalist cause). Campbell decided to trust Dolly, who led the British down a path through the swamps, emerging just behind the American left.

As the British marched out of the swamp, an officer climbed a nearby tree to look out for the Americans. Once the British had got into formation, the officer in the tree gave a signal with a wave of his hat, and Campbell ordered his men to charge. Howe was shocked to find the British on his left, having believed that he was protected against flanking maneuvers by the swamps. Faced with attacks on his front and flank, Howe ordered a retreat; the panicked Americans fled through the Musgrove Swamp Causeway to the west, with several of them drowning in the process. The battle had not lasted long; the Americans had lost 83 dead and 453 captured, while the British had lost only 3 killed and 10 wounded. Afterwards, Campbell continued his march and captured Savannah without additional fighting; Savannah was, therefore, the first southern city to fall to the British, kicking off their southern strategy.

Interlude: January - September 1779

On 19 January 1779, British General Augustine Prévost arrived in Savannah from Florida and assumed overall command. Hoping to consolidate Britain’s foothold in Georgia, Prévost sent troops to capture the outlying towns; Colonel Campbell seized control of Augusta, Georgia, while another detachment of British troops marched up the coast to occupy Beaufort, South Carolina, located on Port Royal Island. By July, the British felt confident enough in their control to invite Sir James Wright, the prewar royal governor of Georgia, back to resume the governance of the colony. It seemed that Georgia had become the first state to fall back under British subjugation.

Meanwhile, Robert Howe was court-martialed for the loss of Savannah. Although he was ultimately exonerated of any wrongdoing, he was removed from command anyway, and was replaced with Major General Benjamin Lincoln. Lincoln, who had proved his mettle in the northern theater during the Saratoga Campaign (June to October 1777) was determined to retake Savannah and spent the spring and summer of 1779 building up his forces. By July, he had around 6,000 men at his headquarters in Charleston, South Carolina. But this would not be enough; if Lincoln wanted to retake Savannah, he would need naval support. He therefore wrote a letter to Charles Henri Hector, Comte d’Estaing, commander of the French fleet, requesting his support.

D'Estaing had arrived in North America the previous summer, shortly after France had entered the war as a United States ally. He had attempted to aid the Americans in the Siege of Newport, Rhode Island, but, after his fleet was damaged by a storm, he sailed off to Boston to make repairs, forcing the Americans to fend for themselves at the ensuing Battle of Rhode Island (29 August 1778). This caused friction in the new Franco-American alliance, leading a frustrated d’Estaing to sail off into the West Indies, to try and defeat the British warships there. D’Estaing had just captured Grenada when, in July 1779, he received Lincoln’s entreaties for assistance. No doubt hoping to clear his name after the Rhode Island fiasco, d’Estaing sent five ships to Charleston to announce his cooperation and sailed the rest of his fleet – including 33 ships, over 2,000 cannons, and over 4,000 French soldiers – toward Georgia. When, on 3 September, General Lincoln received word of d’Estaing’s intentions, he immediately left Charleston and marched his army south toward Savannah.

The Siege Begins: 12 September - 8 October 1779

In early September 1779, d’Estaing’s French fleet approached the coast of Georgia. Its coming was so sudden and unexpected that it was able to overtake and capture two British ships, the 50-gun Experiment and the frigate Ariel; amongst the booty taken from these ships was the £30,000 payroll for the Savannah garrison. On 12 September, d’Estaing reached the Savannah River and began landing troops at Beaulieu, a location about 14 miles south of Savannah. After landing about 1,500 men, bad weather prevented him from unloading any more until the 16th, when it cleared up enough for him to finish disembarking his troops. By this point, d’Estaing was joined by the advance American units, which included a militia brigade under Brigadier General Lachlan McIntosh, and 200 cavalry troopers under the Polish nobleman Count Casimir Pulaski.

On 16 September, d’Estaing approached Savannah with his army, demanding that the British garrison surrender “to the arms of the King of France” (Boatner, 984). Prévost requested 24 hours to consider, which was duly granted. Unbeknownst to the allies, Prévost was merely playing for time, as he was awaiting Lt. Colonel John Maitland’s return from Beaufort, South Carolina. Once Maitland marched back into Savannah with around 800 men, Prévost felt confident enough to refuse d’Estaing’s demand for surrender; he had over 3,200 British regulars at his disposal, as well as a number of Loyalist civilians and runaway slaves who would aid him. Upon receiving the British refusal, d’Estaing began to lay siege.

General Lincoln arrived on the evening of the 16th with the bulk of his army. Just as had happened the year before at Newport, the American and French commanders did not get along; d’Estaing’s decision to call for a surrender without waiting for Lincoln’s arrival did not sit well with the American officers, while d’Estaing felt that his rank and nobility precluded him from having to bow and scrape to the Americans. According to one British officer, Lincoln became “so much despised by the French as to not be allowed to go into their camp” (Boatner, 984). Still, Lincoln agreed to support the siege, and, on the night of 24 September, the American guns were brought up and put into position. During the evening of 3 October, the allied artillery began to bombard Savannah, keeping up the cannonade for five days.

In the meantime, d’Estaing was growing impatient. His fleet captains were urging him to abandon the siege; the fleet was in dire need of repairs, its position off the Georgia coast left it vulnerable to damage from hurricanes or attack from a British fleet, and the French sailors had been afflicted with scurvy and dysentery so that they were dying at a rate of 35 men per day. D’Estaing had initially agreed to stay on shore for only ten days, which his engineers had assured him would be enough time to finish the siege. But once three weeks had passed, and Savannah seemed no closer to falling, d’Estaing decided he had had enough. On 8 October he convened a war council, after which he decided that an assault would be made on the British positions before dawn on the following day.

The Assault: 9 October 1779

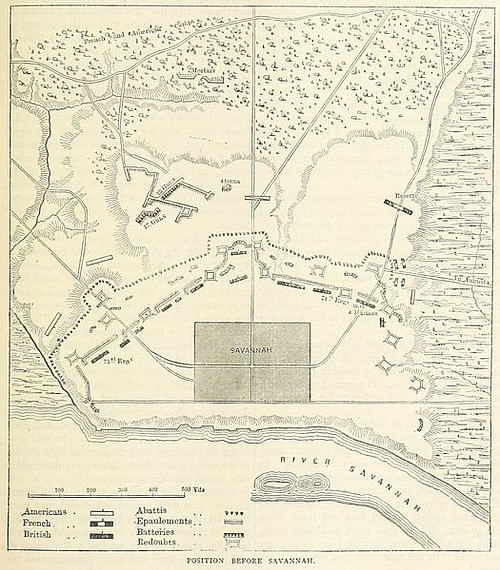

Prévost had spent the previous weeks preparing for an allied attack. He had constructed a series of earthworks in a half-circle to cover the land approaches to Savannah; while the Franco-American artillery bombardment had done much damage to Savannah itself and had killed many civilians, the soldiers within these earthworks had mostly gone unharmed. Prévost had also built a redoubt atop Spring Hill, the high ground that commanded the approaches to Savannah, initially garrisoning it with only dismounted dragoons and a company of Loyalist militia; Prévost eventually decided to strengthen this garrison, sending in companies of British regulars, including elite grenadiers and marines. In the woods on the far right of his line, Prévost established the so-called ‘Sailor’s Battery’, which consisted of several 9-pound cannons manned by sailors. Additional redoubts were constructed to plug any gaps in the British line of trenches.

The allies planned their attack to concentrate against Spring Hill, just as Prévost had expected. Although d’Estaing knew about the redoubt atop the hill, he believed it to be lightly defended by untrained Loyalists and thought that it could easily be stormed. At 4 am on 9 October, the allied attack began, with 4,500 French and American troops marching off in a single column. A thick fog covered the battlefield, which disorientated the allied soldiers, causing some of them to get lost in the swamps in front of Spring Hill. Finally, the allied troops reached the hill and began their assault. Colonel John Laurens led the 2nd South Carolina Regiment up the hill, under heavy fire from the British. Laurens’ Continentals were able to break into the outer works of the redoubt, planting the Crescent flag of South Carolina and the French flag on the parapets.

But no sooner had the allies hoisted these flags when they were hit by a devastating volley from the troops inside the main part of the redoubt; these were not the untrained Loyalists that d’Estaing had expected, but the British regulars who had been sent to reinforce the redoubt during the night. Several American and French officers went down, causing the rest of the troops to start to panic. Noticing this, British Major Beamsley Glazier led a detachment of grenadiers and marines out of the redoubt in a sortie, slamming into Laurens’ wavering troops. As the allied soldiers were slowly rolled off the hill, other British troops ran out to join in Glazier’s counterattack. After an hour of confused and bloody hand-to-hand fighting in the pre-dawn dark, the French and Americans were finally driven away from Spring Hill and sent running back to their camp.

As the fight raged at Spring Hill, Casimir Pulaski was leading his cavalry along the British line, trying to find an opening in their fortifications that he could exploit. In doing so, the cavalry became bogged down by British fire and Pulaski was mortally wounded; considered the father of the American cavalry, his loss was a heavy blow to the Patriot cause. The cavalry retreated after the fall of their commander, running straight into Laurens’ fleeing troops, which only added to the confusion. D’Estaing, trying to rally the retreating French soldiers, was wounded twice and had to be carried from the battlefield. General McIntosh, whose Continental brigade was still fresh, attempted to travel through Yamacraw Swamp to hit the enemy's right flank. However, McIntosh’s men became stuck in the swamp, making easy targets for the British artillery which blasted them to shreds.

The sun rose at 6 am, casting light on a torn-up battlefield littered with the dead and dying. The allies had lost 244 killed, 584 wounded, and 120 captured; of the nearly 1,000 total casualties, around 650 were French. The British, meanwhile, lost around 40 killed, 63 wounded, and 52 missing. Although the actual fighting had lasted for less than two hours, it had been one of the bloodiest battles of the war.

Aftermath

After their initial retreat, the allies declined to renew the assault; fog still rendered visibility low, and the staggering losses suffered by the French and Americans made it hard to stomach a second assault. Lincoln urged d’Estaing to continue the siege but the French admiral, cognizant of the troubles facing his fleet, refused. On 20 October, the French returned to their ships and sailed away. Lincoln, unable to continue the siege on his own, began his retreat to Charleston the same day. The Americans felt resentful toward the French for abandoning them a second time, with many beginning to question how helpful the French alliance actually was. Several American officers and men came to the bitter conclusion that if they wanted independence, they would have to win it themselves.

When British General Clinton received news of the victory at Savannah, he was elated, referring to it as “the greatest event that has happened in the whole war” (Boatner, 988). It proved to him that the proposed British strategy was indeed possible, and he began preparing for a large-scale invasion of the American South. The next year, Clinton would sail to South Carolina and begin the Siege of Charleston (29 March to 12 May 1780) which would prove one of the greatest British victories of the war. The ensuing war in the south, waged mostly in the Carolinas and Virginia, would comprise the final stage of the active Revolutionary War, culminating in a Franco-American victory at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781).