The Siege of Charleston (29 March to 12 May 1780) was a major military operation during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Hoping to establish a foothold in the American South, British commander-in-chief Sir Henry Clinton led an attack on Charleston, South Carolina, capturing the city after a six-week siege. It was one of the worst American defeats of the war.

Background: Britain Invades the South

For the first three years of the war, British strategy had focused on the northern United States, with most of the fighting taking place in the New England colonies and Middle Colonies. But after several British campaigns in the north met with failure, Britain shifted its attention to the American South. The south was supposedly bursting with Loyalists, who were awaiting the arrival of a British army to revolt en masse and cast off their revolutionary governments. Additionally, the south produced most of the profitable cash crops of the United States, including indigo, rice, and tobacco. The Americans were using the revenue from these crops to purchase war supplies. If the south were to fall under British control, therefore, the Americans would be less capable of funding their war effort.

Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British army in North America, decided to probe the American defenses in the south before committing to a full-scale invasion. In November 1778, he dispatched a small expeditionary force of 3,500 men to seize control of Savannah, Georgia. On 29 December, after a brief skirmish with the Americans, the British captured Savannah before consolidating their foothold in the south by occupying the surrounding towns. But their control of Georgia would not go unchallenged, as Major General Benjamin Lincoln, commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army, was determined to prevent the state from falling back under British subjugation. After joining forces with 4,000 French troops under Charles Henri Hector, Comte d’Estaing, Lincoln laid siege to Savannah on 16 September 1779. But the siege took longer than anticipated and d’Estaing, anxious that his fleet was left vulnerable to British attack, grew impatient and ordered a direct assault. However, the Franco-American assault on Savannah, which took place on 9 October 1779, was bloodily repulsed. The dispirited allies abandoned the siege of Savannah shortly thereafter, leaving Georgia in British hands.

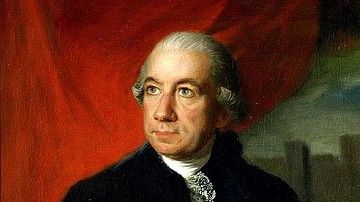

When Clinton heard the news of the British victory at Savannah, he was elated, referring to it as “the greatest event that has happened in the whole war” (Boatner, 988). The Savannah experiment having proved successful, Clinton immediately turned his attention toward a larger prize: Charleston, South Carolina. Boasting a population of 12,000 residents, Charleston was one of the four most important cities in British North America (the others being New York, Boston, and Philadelphia). It was the largest city in the south, its bustling port the center of much of the region’s wealth. Clinton himself had tried to capture it three years earlier but had been defeated at the Battle of Sullivan’s Island (28 June 1776); he was not about to let the city defeat him a second time. On 26 December 1779, Clinton placed German General Wilhelm von Knyphausen in charge of British-occupied New York City, leaving him with 10,000 men. Clinton, his second-in-command Lord Charles Cornwallis, and the remaining 8,500 British and German soldiers then boarded a fleet of 90 transport ships sitting in New York Harbor. Escorted by 14 Royal Navy warships under Vice Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot, the transports then weighed anchor and set sail for Charleston.

A Stormy Expedition

The voyage was an unpleasant one. One German officer, Johann Hinrichs of the Jaeger Corps, recorded that every day saw cold, miserable weather that often followed a similar pattern: “storm, rain, hail, snow, and waves breaking over the cabin” (quoted in Middlekauff, 444). Indeed, the biting winter wind whipped up tall waves that rocked the ships violently back and forth and often flooded the decks. One transport ship, the Anna, was swept out into the middle of the Atlantic, taking its 200 German infantrymen with it. Another transport, the George, was wrecked; while most of the soldiers onboard were rescued, a great deal of valuable war equipment, including most of the transport’s horses, was dragged to the bottom of the sea. At the end of January 1780, the harrowing journey came to an end, as the British ships put in at Tybee Island, at the mouth of the Savannah River, to regroup. Clinton waited for the straggling ships to catch up before sailing back north, hugging the coastline until they reached South Carolina’s Edisto Inlet on 11 February.

After some heated disagreement with Admiral Arbuthnot about where to land the army – Clinton, though a gifted strategist, was paranoid that his military peers were always out to undermine him, leading him to butt heads with almost everyone – the commander-in-chief decided to land his men on Simmons Island (modern Seabrook Island) about 30 miles south of Charleston. Clinton elected to wait here as reinforcements arrived from Georgia and New York, bringing his numbers up to around 10,000 men. He established supply depots and powder magazines in the surrounding areas and wrote to British military outposts in Florida and the Bahamas, requesting that any unused cannon be shipped to the Carolinas.

Charleston’s Defenses

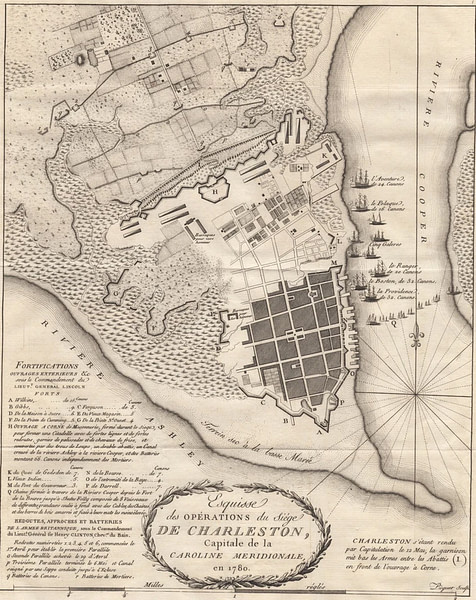

The Patriots could not miss spotting the massive British expedition assembling on Simmons Island and were quick to guess its target. General Lincoln immediately looked to the defense of Charleston. His army was not a large one; he had around 1,200 Continentals (regular soldiers) from Virginia and South Carolina, around 2,000 South Carolina militia, and 380 men from Pulaski’s Legion. A small flotilla from the Continental Navy, led by Commodore Abraham Whipple, sat in the harbor. Whipple had eight ships, several of which had been purchased from the French. Entry to Charleston Harbor was defended by Fort Moultrie to the east and Fort Johnson to the west, although both forts had slipped into a sorry state of disrepair. Lincoln anticipated that the main British attack would come from the sea and quickly sent men to repair the forts. The harbor was also defended by a sandbar that would, hopefully, prevent the passage of any heavy warships.

Since Lincoln expected the British to attack via the harbor, he neglected the defenses on Charleston’s landward side. At the heart of the landward defenses was an 18-gun citadel constructed out of “tappy”, a material made from oyster shells, lime, sand, and water. The citadel had redoubts positioned on either side, but these remained unfinished. The peninsula on which Charleston sat was located in the confluence between the Ashley and Cooper Rivers; six small forts were located along the Ashley River, guarding overland passes to the city, with seven forts located along the Cooper.

The Siege Begins

On 20 March 1780, Admiral Arbuthnot’s fleet sailed into view of Charleston harbor. Despite the admiral’s natural cautiousness, he nevertheless managed to get six small frigates over the sandbar and into the harbor. Commodore Whipple, who had not expected the Royal Navy ships to enter the harbor so soon, decided against attacking; instead, he sailed his ships into the mouth of the Cooper River and scuttled them, creating a barrier with the wreckage. His sailors were then sent into Charleston to help man the cannons. On 8 April, Arbuthnot managed to get all 14 of his warships past the sandbar and into the harbor, sailing past the practically useless cannons of Fort Moultrie.

General Clinton, meanwhile, had landed his army on the South Carolina mainland at Drayton’s Landing, 12 miles above Charleston. On 29 March, Clinton’s men crossed the Ashley River and, on 1 April, moved within 800 yards of Charleston’s landside defenses. Lincoln was now surrounded, boxed in by the British from both land and sea. On the landward side, the British dug in. They created a parallel, a series of trenches and redoubts that mirrored the American fortifications. The sandy soil of Charleston peninsula made for easy digging, and within ten days the first British parallel was complete. Clinton and Arbuthnot demanded Lincoln’s surrender, but the American general refused, whereupon work was started on a second parallel, even closer to the American line.

The construction of the parallels was overseen by Major James Moncrieff, the chief British engineer, who organized troops into work parties that were sometimes as large as 500 men. One feature of Moncrieff’s trenches was his use of mantelets, which were heavy wooden frames ten feet high, fourteen feet long, and situated on three legs. Sixteen of these mantelets would be put together to form the walls of a redoubt, with workmen piling sand or dirt against the outside of the wall. This was not easy work; the South Carolina air was hot and unforgiving, and vicious sand fleas bit the workers’ ankles, arms, and faces.

But these troubles were soon forgotten when the British trenches came within range of the American artillery. Every now and then, the Patriot cannons would roar to life, the British and German soldiers bracing themselves as the ground around them was chewed up by the cannon fire. The flat terrain of the peninsula turned the British into easy targets for the American gunners, who did not fire conventional rounds. Low on actual ammunition, the Americans instead fired canisters filled with various projectiles including shovels, pickaxes, hatchets, flat irons, and even shards of broken glass. The wounds inflicted by these canisters were devastating, as limbs were torn off and bones were shattered. The British artillery returned fire once it came close enough, firing canisters of their own with 100 bullets each.

The British Close In

As the British trenches crept closer to Charleston, Clinton became worried that the Americans could still escape by way of the Cooper River. On 14 April, he dispatched Colonel Banastre Tarleton and the elite Loyalist unit known as the British Legion to seize Monck’s Corner, one of the main passes over the Cooper River. Tarleton surprised the American troops guarding Monck’s Corner and chased them off after a brief skirmish; by the end of the next day, all major passes over the Cooper within six miles of Charleston were controlled by the British. The American army in the city was now well and truly trapped.

On 19 April, the British finished their second parallel and got to work on their third; they were now within 250 yards of the walls of Charleston. General Lincoln, seeing that the end was near, convened a war council in which he suggested that they surrender. Lt. Governor Christopher Gadsden, who was sitting in on the council despite his civilian status, would not hear of it, and scolded Lincoln for even considering abandoning Charleston. The next day, Gadsden returned to Lincoln’s headquarters with a party of other civilian leaders, all of whom begged Lincoln not to abandon them to the British. The general begrudgingly folded, and the siege continued.

At dawn on 24 April, 200 Virginians and Carolinians made a sortie against the British troops who were working on the third parallel. The British were taken by surprise and fled back to the second line of trenches; 50 British troops had been killed or wounded in the attack, with another 12 taken prisoner. The unexpected attack made the British skittish; the next night, work on the third parallel was again stopped when a sudden noise convinced the besiegers that the Americans were launching another sortie, causing them to panic and abandon their posts. Only once it became clear that no attack was forthcoming did they resume their work.

End of the Siege

By the end of the first week of May, British sappers had dug right up to the base of the American fortifications. Artillery fire intensified on both sides, and before long, the peninsula had turned into a hellscape, filled with craters. and strewn with bodies. On 9 May, the British artillery got close enough to fire into the wooden houses of Charleston, engulfing the buildings in flames. One British officer hauntingly remembered how the screams of women and children accompanied every British cannon salvo that was fired into the city (Fleming, 111). Several British officers let out a cheer when Charleston caught fire, but they were quickly scolded by Clinton, who told them that it was “absurd, impolite, and inhuman to burn a town you mean to occupy” (Middlekauff, 450).

On 11 May, Gadsden and the other leading Charleston citizens approached Lincoln, asking him to surrender the city on the best possible terms. Lincoln met with Clinton under a parley, asking that his army be allowed to leave the city with the full honors of war. Clinton flatly refused, stating he would accept nothing other than unconditional surrender. Lincoln accepted and, at 11 am on 12 May 1780, the Continental soldiers marched out of the city and into British captivity. The American officers were initially allowed to keep their swords, but after several of them were heard shouting “Long live Congress!”, this honor was revoked. The militia, unlike the Continentals, were allowed to go home on parole. Ultimately, the British recorded the capture of 7 American generals, 5,466 Continental officers and men (many of whom had been too old or sick to take part in the siege), 5,316 muskets, 15 regimental colors, and about 33,000 rounds of small arms ammunition. This was the largest American force to surrender to an enemy army before the Battle of Harper’s Ferry in 1862.

Three days after Lincoln’s surrender, a loaded musket was carelessly thrown into a warehouse where many casks of gunpowder were stored. The musket went off, causing a massive explosion. Six neighboring buildings, including a brothel and a poorhouse, caught fire, leading to hours of further chaos and destruction. When the flames died down, around 200 people were dead, killed in the initial blast or in the ensuing fire; the casualties included soldiers and civilians alike, British, American, and German. One German officer described the horror, noting in his diary how the heavily burned men and women had “writhed like worms on the ground”, some of their bodies “so mutilated that one could not make out a human figure” (quoted in Middlekauff, 212). Naturally, the British occupiers blamed an American saboteur, while the Americans blamed British carelessness for the tragedy. No matter who was to blame, the warehouse explosion marked a horrific end to a nightmarish siege.

Casualties & Aftermath

The Siege of Charleston was undoubtedly one of the most important British victories of the war; Clinton had captured the most vital city in the American South and had forced the surrender of an entire Patriot army. Aside from those affected by the warehouse explosion, the Americans had lost around 90 killed and 140 wounded during the course of the siege, compared to around 76 killed and 189 wounded for the British and Germans besiegers. Adding in the unknown civilian losses, and the American prisoners-of-war who would later die of the dreadful conditions of the British prisons, the total death toll was likely much higher.

Clinton remained in Charleston long enough to issue a proclamation offering a pardon to any rebel who swore allegiance to the king. Then, on 5 June, he took 4,000 men and sailed back to New York City, believing he was needed there to defend against a potential Franco-American attack. His second-in-command, Lord Cornwallis, was left in command of the southern army, with orders to finish subduing the Carolinas. After the loss of Lincoln’s army, the southern Patriots hastily put together another army to defend against Cornwallis, only for this force to also meet with disaster at the Battle of Camden (16 August 1780).