The bomber raid on Dresden was a controversial and highly destructive combined operation by Royal Air Force Lancaster bombers and United States Air Force B-17 Flying Fortress bombers on 13, 14, and 15 February and 2 March 1945. The raid was part of Operation Thunderclap, which aimed to strike Berlin and other cities in eastern Germany, causing logistical chaos to support the Russian advance on the Eastern Front.

Dresden was a key transportation hub and possessed several factories important to the German military. However, the strike against civilians, consequent firestorm, and high death toll led to some questioning the necessity to hit the city at all. The Western Allies had promised the USSR that they would conduct bombing raids in eastern Germany to support the Eastern Front, but Dresden seemed to some to be one blitz too many in a war that Germany was already well on the way to losing. Around 30,000 civilians were killed in the raid (although estimations vary wildly), and Dresden was all but flattened. The raid has raised questions ever since as to the validity of area bombing in the Second World War (1939-45) and its moral repercussions.

The Thousand-Bomber Raids

The Commander-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command from February 1942 to the end of the Second World War was Arthur Harris (1892-1984), and he had very definite ideas on the best and quickest way to win the conflict. Harris, and it should be noted others in high command such as Chief of the Air Staff Sir Charles Portal (1893-1971) and the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965), firmly believed that extensive and sustained area bombing (aka carpet bombing) – bombing a large area simultaneously – conducted against Germany's most important industrial cities might well bring about an early surrender.

There were other reasons for the raids on cities, notably that in the early years of the war because a land invasion in Europe was impossible, air attacks were the only way to directly hit Germany and its allies. Another reason was to crush German civilian morale and boost civilian morale at home after the devastation caused when the Luftwaffe (German airforce) bombed British cities and carried out the London Blitz. Finally, strategic targets like factories and U-boat bases proved too difficult to hit accurately with the technology available, considering that such attacks had to be conducted in daylight, which made bombers easy prey to enemy fighter planes like the Messerschmitt Bf 109. Reconnaissance showed that only one in three aircraft dropped its bombs within 5 miles (8 km) of the intended target. Area bombing seemed the much better use of resources. The downside, of course, was that many civilians would be killed in such raids. While many military commanders and politicians had serious misgivings about attacking cities, both sides did conduct such attacks.

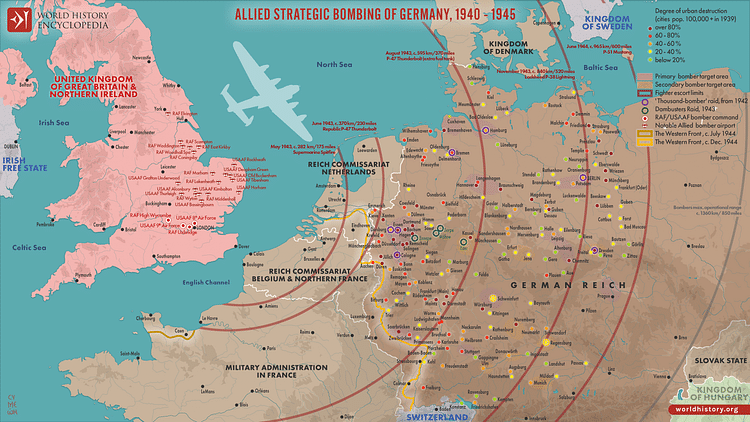

Massive bombing raids were, then, conducted, very often containing around 1,000 heavy bombers, against specific German cities and the Ruhr industrial area. The first such attack was the thousand-bomber raid on Cologne in 1942. Other cities hit the same way included Bremen, Essen, and Berlin – the capital suffered a sustained campaign from November 1943 until March 1944, known as the Battle of Berlin (Air). The most devastating attack of all was Operation Gomorrah against Hamburg in the summer of 1943 when the RAF and the United States Air Force (USAAF) combined their bomber strength. This raid, conducted over several days, caused a firestorm, which resulted in 46,000 civilian deaths.

The British considered the big raids successful. Factories and infrastructures were damaged (although production was usually revived a few months after a raid), and vital resources were diverted to defend Germany. The idea of amassing such a large force of bombers to overwhelm the enemy air defences had indeed worked and reduced bomber losses to an acceptable level. German civilian morale did not crumble, though, despite the onslaught, but even if it had, it is difficult to imagine what ordinary people could have done against the totalitarian regime in which they lived. The logistics involved in the "1,000-bomber raids" meant they could not be conducted in rapid succession on different cities, a tactic that might have had better results in crushing civilian morale.

Thunderclap: Why Dresden Was Targeted

In any case, Arthur Harris remained undeterred, and he planned more big raids. The Air Chief Marshall again received support from the highest level for what became known as Operation Thunderclap, the bombing of Berlin (yet again), various targets in Eastern Germany such as Magdeburg and Chemnitz, and the large city of Dresden, the capital of Saxony. The Western Allies were motivated to continue conducting heavy bombing since the USSR was insisting some help in that direction be given them as the Red Army pushed ever-westwards. The Western Allies were especially keen to make good on their promise of aerial assistance to help break down German resistance in the east before all the Allied leaders met at Yalta in February 1945. Already, the stream of civilian refugees surging westwards was causing havoc with the German transport networks. It was hoped that Thunderclap would cause even more disruption, particularly to the resupply of German troops on the rapidly evolving eastern front. The fact that both air forces were deployed over Dresden illustrates that this was a joint mission given approval at the very highest level, and it was not, as is commonly believed, the sole responsibility of 'Bomber' Harris.

The choice of Dresden was itself controversial since the city did not possess as much heavy industry as other potential targets, which was why Dresden had only been attacked two times previously in the war in October 1944 and January 1945, both times by USAAF bombers primarily aiming for an oil refinery (but also inadvertently hitting the city centre). However, Dresden, contrary to popular myth, was an industrial city. The Allies were not first and foremost intent on bombing civilians. Important industrial targets which the Allies hoped to wipe out with their carpet-bombing strategy at Dresden included the oil refineries outside the city, the Siemens glass factory, the Zeiss-Ikon optical factory, various factories crucial to anti-aircraft defences, factories making cockpit parts for Messerschmitt fighter planes, and a Junkers aeroplane engine factory. It is estimated that 10,000 people living in Dresden worked in these factories. The German authorities insisted after the raid that Dresden's factories were mostly involved in making toothpaste and talcum powder, but this was mere propaganda. Significantly, the same German authorities had never listed Dresden as an 'open city', that is one with no military targets.

Besides industries important to Germany's war effort, Dresden was a transportation hub, and damage to transport infrastructure, particularly the train marshalling yards, would have serious consequences for the supplies of men and material to the Eastern Front, which was then less than 100 miles to the east (160 km). It would also disrupt the passage of refugees moving from the east to the west. That specific bomber groups were directed to target the transportation network of Dresden is attested by the RAF and USAAF pilots themselves who learnt of their targets from their pre- and post-mission briefings.

Other points to consider are that Dresden was not very well-defended in terms of anti-aircraft guns since most had been moved to the Eastern Front, and it was easier for bombers to find than many other targets due to its location on a major river. Sadly for posterity, Dresden had much fine architecture and a global reputation for its fine porcelain manufacturing, which included the nearby potteries at Meissen. The fine old city would never be the same again.

The Bombers & Attack Strategy

The RAF's best heavy bomber was the four-engined Lancaster bomber, capable of carrying a bomb load of up to 14,000 lbs (6,350 kg). 796 RAF Lancasters and 9 de Havilland Mosquito fighter-bombers (target markers) made up the raiding force against Dresden. The USAAF part of the operation used several hundred Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, each capable of carrying a bomb load of around 6,000 lb (2,722 kg).

The RAF attack strategy was to use the bomber stream formation, which had first been used against Cologne back in 1942. Designed to overwhelm enemy defences, the bomber stream was a tight formation of the entire bomber force, although it could still cover a length of up to 70 miles (112 km) and a depth of around 4,000 feet (1,200 m). The staggered height of the bombers reduced the chances of mid-air collisions. Harris had added a new tactic to this, and it would be applied to the Dresden raid. This was to split the bomber force into two separate groups, the second following on from the first after an interval of around three hours. The idea was that when near or over the target, enemy fighters would engage the first wave but then have to refuel and rearm, which might leave the second wave of bombers unmolested.

Bombing Dresden

Dresden was selected to be hit in early February, but poor weather conditions delayed the operation. The original plan had been for the USAAF to conduct a daylight raid on the city, which would then be followed up by an RAF night-bombing attack. The bad weather necessitated the cancellation of the USAAF part of the operation. On the night of 13 February, still with far from ideal weather conditions, the RAF bomber stream took off from Britain.

The bombers were guided on a moonless night into the target area by the city's location along the River Elbe. Reaching the target, successive waves of bombers dropped their loads every few minutes. The whole force of two large groups passed over Dresden in a total attack period of less than five hours. As was by then usual, the bombers dropped a mix of explosive bombs (1,478 tons in all) and incendiary bombs (1,182 tons). The first type destroyed the roofs and internal structures of buildings, and then the second type was dropped to create fires within the ruins. The lethal combination, as at Hamburg two years earlier, created a terrible firestorm. The fire services could not cope with the scale of the damage or the raging fires, which created very strong winds and extreme heat.

Ursula Gray, a Dresden resident, gives the following eyewitness account of her view on the ground during the bombing raid:

The only idea was to get out in an open space and our house was situated close to a beautiful area called The Great Garden, which had lovely old oak trees, three hundred years old, and beautiful little pavilions. By that time already there were buildings falling apart and you had to make your way over stones and rubble and killed people and you just didn't care – you stepped on whatever you could just to get out and away from it all. Many other people already had gathered. They had the same idea, to get away from the burning houses, from that ocean of fire and bombing, and huddled up under the trees. While we were sitting there they sent bombs which kind of illuminated the city in red and green and for a moment it was a very strange picture. I will never forget it: it looked like windows of a cathedral. After this raid was over the city was just an ocean of fire, thousands and thousands of people killed, killed right beside us, around us, and screams and smells. The most gruesome picture was the nakedness of the people killed by the bombing: the tornado or the air pressure of the bombs had apparently torn their clothes to shreds. (Holmes, 311-2)

To add to the misery of Dresden's civilians, the USAAF then carried out the raid originally planned for the day before. On 14 February, 311 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers dropped their loads on Dresden. The bombers' aiming point was the train yards. The escorting USAAF fighters, once the bombers had turned back, "followed by machine-gunning and strafing of the streets…which had become a standard tactic of US fighters after their escort duties had been completed" (Neillands, 366). More USAAF bombers returned on 15 February and 2 March.

As the homeless fled the city, Gray again describes the scene:

The third raid was by the Americans and they concentrated on strafing people. There was no defence., we had no defence at all, and they concentrated on getting these people who were trying to save their lives and get out into the suburbs and go into the country. All the people who were gathered on the meadows along the river, they went right down and strafed the people and killed them one by one.

(Holmes, 439)

Another view of the bombing comes from Ben Halfgott, a Jewish prisoner in the nearby Nazi concentration camp:

We saw the bombing of Dresden from the satellite camp at Schlieben, where we worked with German women making Panzerfausts, anti-tank rockets. The fires in the sky, a huge red glow – it was like heaven for us. We went out to watch and it was glorious, for we knew that the end of the war must be near and our salvation was at hand. I was fifteen years old when the Russians arrived and I weighed 50 kilos. You could see all my bones.

(Neillands, 359)

Legacy

The RAF and the USAAF deemed the raid a success. Dresden's light air defences meant that only six Lancasters were lost over the city. Three more bombers crashed on the return to Britain. Thunderclap's objectives became public knowledge following a leak at a press conference, and a story then appeared written by an Associated Press reporter that the Allies were resorting to "terror bombing" (a phrase the Nazi propaganda machine had long been using). The politicians did an about-face, including Churchill, who wrote to the British Chiefs of Staff in March 1945 that "The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing. I am of the opinion that military objectives must henceforward be more strictly studied in our own interests rather than that of the enemy" (Neillands, 372).

It is estimated there were around 30,000 civilian deaths in the four Dresden raids, although historians cannot agree, and some estimates are considerably higher. The numbers were difficult to accurately assess because of the high number of refugees in the city at that time. For an increasing number of people in the West, Dresden was one bombing raid too many. The Pointblank Directive (June 1942) of the Allied high command had agreed that bombing targets of military and strategic value was the priority over civilian targets in preparation for the forthcoming land operations in Europe (although the directive was ambiguous since it did include lowering civilian morale as a legitimate objective). Perhaps the proximity to the closing stages of the war affected public opinion more than the earlier raids had done. At the end of the war, Harris became something of a scapegoat for the area bombing campaign, despite the obvious fact that others had repeatedly supported the execution of the strategy. It was true that some high-level commanders had preferred to attack targets specifically connected to Germany's oil supply, and there were still others who wished to attack only transport networks, but the majority had gone along with the area bombing campaign. Harris remained convinced of the validity of bombing cities as the best way to ultimately lessen the inevitable casualties of land operations, commenting that he did not consider "the whole of the remaining cities of Germany as worth the bones of one British Grenadier" (Dear, 242).

There is a continuing debate as to whether the bombing of cities during the war can be considered a war crime. That both sides bombed civilians is not an argument against such a classification, certainly. There is the important distinction that the German cities targeted were industrial cities (and not, for example, seaside resorts or spa towns), and both the RAF and USAAF reiterated in public announcements that their raids were aimed at industrial targets, even if the bombs, in reality, fell on civilians. It may also be inappropriate to judge history through the lens of the present and with the gift of hindsight. As the aviation historian R. Neillands notes:

The order to attack Dresden was not illegal. There were cogent reasons for bombing Dresden and, though hindsight indicates that it probably was an unnecessary operation, that was not the opinion at the time. (393)

Despite the moral questions posed following the Dresden raid, that city was not to be the last to be heavily bombed in the war. In 1945, many Japanese cities faced equally massive and even more destructive bombing raids as the US sought to avoid a dangerous and lengthy land invasion, a campaign of calculated terror which culminated in the total devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki using atomic bombs.