How the World Was Made is a creation story of the Cherokee nation, which, like many such tales of the Native peoples of North America, begins with a world covered by water from which dry land is formed and natural order created by beings of a higher realm. The story explains why things are the way they are.

Like the Lakota Sioux Creation Story and the Cheyenne Creation Story, among many others, How the World Was Made begins with a world of undifferentiated chaos out of which the animals of Galun lati (the higher realm) bring order. As the story unfolds, explanations are given for why there are valleys and mountains, why the crawfish is red in color and why the Cherokee will not eat it, why the sun moves across the sky as it does, how animals came to have certain characteristics, and why women can only give birth to one child a year.

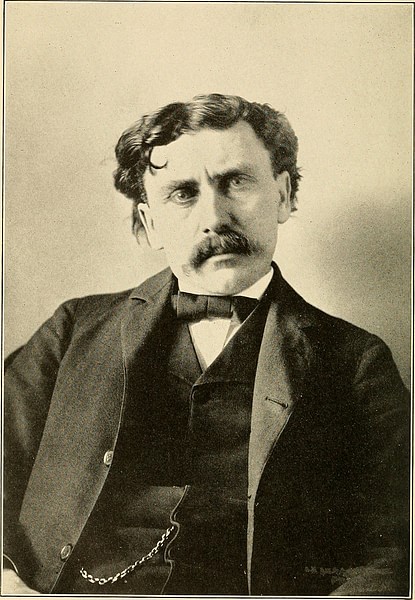

The story was first translated into English by the American ethnographer James Mooney (l. 1861-1921) who lived with the Cherokee and recorded their lore and legends, compiled in his book Myths of the Cherokee (1900). The story may be hundreds or thousands of years old. There is no way to date the piece as it was passed down through oral tradition by Cherokee storytellers long before Mooney heard it told. As he writes, concerning the dating of such pieces:

As our grandmothers begin [a story with] "Once upon a time," so the Cherokee storyteller introduces his narrative by saying, "This is what the old men told me when I was a boy." (232)

This being the case, the tale assumes a timeless quality in keeping with the Cherokee understanding of time as cyclical and unchanging. Events differ year to year according to human understanding but, to the universe, any given time is all time ever since the creation of the world.

Cherokee Beliefs & Storytelling

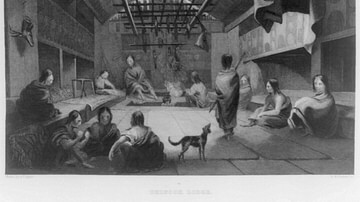

The traditional Cherokee understanding of the physical world, at the time Mooney came in contact with them, was that it was a middle land between a higher realm of benevolent spirits and the great Creator, Unetlanvhi, and a lower world of dark spirits who brought disease, disorder, and death. Humans, in this middle world, were tasked by the Creator with maintaining balance between worlds, in their own lives, in the life of the community, and between humans and the natural world generally. Humans were not seen as superior in any way to the earth, plants, and animals but were understood as stewards who were to maintain created order.

The stories of the Cherokee consistently express this view, not only by explaining why things are as they are but also by emphasizing one's role in caring for the world. In How the World Was Made, this is only hinted at in the last paragraph where the people are depicted as reproducing too quickly. A new child is born every seven days, and the people lack restraint, so the beings of the higher realm place restraints upon them, decreeing that women will only be able to give birth once a year.

This decision was made to maintain order and people were then expected to recognize and maintain said order throughout their lives. Other Cherokee origin tales also touch upon the peoples' responsibility to a given place while, at the same time, explaining why a stream or river runs as it does or a certain rock formation has its distinct features. Mooney writes:

As with other tribes and countries, almost every prominent rock and mountain, every deep bend in the river, in the old Cherokee country has its accompanying legend. It may be a little story that can be told in a paragraph, to account for some natural feature, or it may be one chapter of a myth that has its sequel in a mountain a hundred miles away. As is usual when a people have lived for a long time in the same country, nearly every important myth is localized, thus assuming more definite character. (231)

In the case of How the World Was Made, this "definite character" is global. The entire world is as interconnected as the aspects of one's own land, and what one does with that land affects other places miles and miles away. In the same way, as the animals work together in the creation of this world (inspired or guided silently by Unetlanvhi), so should people work together in maintaining it. Balance was – and still is – a central value of the Cherokee nation and so became, in fact, one's purpose in life: personal balance reflected in communal and, by extension, global balance.

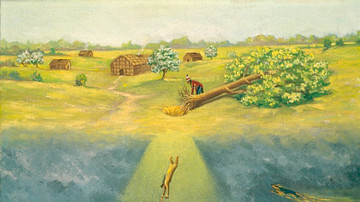

This concept is clearly explored in the Cherokee tale The Origin of Medicine where humans are depicted as having lost balance. The people in the story have forgotten what is due to the natural world and its non-human inhabitants, and so the animals decide to destroy them. The plants, however, side with the humans, providing them with the "medicine" to cure the ills the animals have chosen to unleash. The story, then, explains how medicine came to be and why but also highlights the importance of remembering one's relationship with the natural world and one's obligation to care for it. How the World Was Made provides a model of cooperation among the animals – as well as their failings – to encourage proper understanding of and interaction with all of nature, whether in one's own community or elsewhere.

This same theme is famously dealt with in the story The Origin of Game and Corn in which the two young boys serve as balance to the two parents. According to some scholars, the concept of balance is also at the heart of the game chunkey, played by the Cherokee, Pawnee, Lakota Sioux, Chickasaw, and many others. The two teams in chunkey can represent opposing spiritual forces, and balance is maintained by their respective wins and losses.

Setting & Purpose

The Cherokee nation lived in modern-day Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, part of South Carolina, southern Tennessee, and Virginia. The story, though it addresses the creation of the world, is set in this region, and the mountains and valleys created in paragraph three are the Great Smoky Mountains specifically and the Appalachian Mountains generally. The purpose of the tale is clear – it is an origin myth explaining how the world came to be, why it looks as it does, and why certain animals behave in distinctive ways – but the story also served the same purpose as any local legend in connecting the people with their lands.

As no one really knew how the world was made, any origin story could be true, and setting such a tale in one's own region is a common characteristic of Native American stories, myths, and legends. According to Mooney, How the World Was Made was once part of a larger narrative cycle which had been lost by the time he met the Cherokee through the policies of the US government which uprooted and relocated the people far from their ancestral home. Mooney writes:

The question of the origin of myths is one which affords abundant opportunity for ingenious theories in the absence of any possibility of proof. Those of the Cherokee are too far broken down ever to be woven together again into any long-connected origin legend, such as we find with some tribes, although a few still exhibit a certain sequence which indicates that they once formed component parts of a cycle. (232)

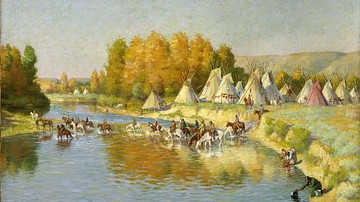

Sent far west to "Indian Territory" (Oklahoma) through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Cherokee continued to keep their lands alive in the communal memory by telling the stories they always had. Among those stories was How the World Was Made with its vivid imagery that would have reminded an audience of the home they had been forced to leave behind, but which still existed, would always exist in memory, and these memories would be passed down to the next generation through the telling of the traditional tales.

Text

The following text is taken from Myths of the Cherokee by James Mooney. The phrase "go to water" in the fifth paragraph is a reference to Cherokee purification rituals in which one would immerse oneself in a flowing stream (sometimes seven times) to wash away one's sins, which were then carried away by the water.

The earth is a great island floating in a sea of water and suspended at each of the four cardinal points by a cord hanging down from the sky vault, which is of solid rock. When the world grows old and worn out, the people will die and the cords will break and let the earth sink down into the ocean, and all will be water again. The Indians are afraid of this.

When all was water, the animals were above in Gälûñ'lätï, beyond the arch; but it was very much crowded, and they were wanting more room. They wondered what was below the water, and at last Dâyuni'sï, "Beaver's Grandchild," the little Water-beetle, offered to go and see if it could learn. It darted in every direction over the surface of the water but could find no firm place to rest. Then it dived to the bottom and came up with some soft mud, which began to grow and spread on every side until it became the island which we call the earth. It was afterward fastened to the sky with four cords, but no one remembers who did this.

At first the earth was flat and very soft and wet. The animals were anxious to get down and sent out different birds to see if it was yet dry, but they found no place to alight and came back again to Gälûñ'lätï. At last, it seemed to be time, and they sent out the Buzzard and told him to go and make ready for them. This was the Great Buzzard, the father of all the buzzards we see now. He flew all over the earth, low down near the ground, and it was still soft. When he reached the Cherokee country, he was very tired, and his wings began to flap and strike the ground, and wherever they struck the earth there was a valley, and where they turned up again there was a mountain. When the animals above saw this, they were afraid that the whole world would be mountains, so they called him back, but the Cherokee country remains full of mountains to this day.

When the earth was dry and the animals came down, it was still dark, so they got the sun and set it in a track to go every day across the island from east to west, just overhead. It was too hot this way, and Tsiska'gïlï', the Red Crawfish, had his shell scorched a bright red, so that his meat was spoiled; and the Cherokee do not eat it. The conjurers put the sun another hand-breadth higher in the air, but it was still too hot. They raised it another time, and another, until it was seven handbreadths high and just under the sky arch. Then it was right, and they left it so. This is why the conjurers call the highest place Gûlkwâ'gine Di'gäl ûñ'lätiyûñ', "the seventh height," because it is seven hand-breadths above the earth. Every day the sun goes along under this arch and returns at night on the upper side to the starting place.

There is another world under this, and it is like ours in everything – animals, plants, and people – save that the seasons are different. The streams that come down from the mountains are the trails by which we reach this underworld, and the springs at their heads are the doorways by which we enter, it, but to do this one must fast and, go to water, and have one of the underground people for a guide. We know that the seasons in the underworld are different from ours because the water in the springs is always warmer in winter and cooler in summer than the outer air.

When the animals and plants were first made – we do not know by whom – they were told to watch and keep awake for seven nights, just as young men now fast and keep awake when they pray to their medicine. They tried to do this, and nearly all were awake through the first night, but the next night several dropped off to sleep, and the third night others were asleep, and then others, until, on the seventh night, of all the animals only the owl, the panther, and one or two more were still awake. To these were given the power to see and to go about in the dark, and to make prey of the birds and animals which must sleep at night. Of the trees only the cedar, the pine, the spruce, the holly, and the laurel were awake to the end, and to them it was given to be always green and to be greatest for medicine, but to the others it was said: "Because you have not endured to the end you shall lose your, hair every winter."

Men came after the animals and plants. At first there were only a brother and sister until he struck her with a fish and told her to multiply, and so it was. In seven days, a child was born to her, and thereafter every seven days another, and they increased very fast until there was danger that the world could not keep them. Then it was made that a woman should have only one child in a year, and it has been so ever since.