Native American women are traditionally held in high regard among the diverse nations, whether a given people are matrilineal or patrilineal. Traditionally, women were not only responsible for raising children and caring for the home but also planted and harvested the crops, built the homes, and engaged in trade, as well as having a voice in government.

The history of the women of the Native peoples of North America attests to their full participation in the community whether as elders and "medicine women" or as skilled agriculturalists and merchants and, in some cases, even warriors. Although hunting and warfare were traditionally the provenance of males, some women became famous for their courage and skill in battle. These women, as well as others in the arts and sciences, are often overlooked because they do not fit the paradigm of what has been accepted as American history.

Pocahontas and Sacagawea are usually the only North American Native women that non-Natives have heard of, but even their narratives have been obscured by legend and half-truths. Many other Native American women have simply been ignored, and among them are most of those listed below. These women, and the nations they were citizens of, include:

- Jigonhsasee – Iroquois

- Pocahontas – Powhattan

- Weetamoo – Wampanoag

- Glory-of-the-Morning – Ho-Chunk/Winnebago

- Sacagawea – Shoshone

- Old-Lady-Grieves-the-Enemy – Pawnee

- Pine Leaf/Woman Chief – Crow

- Lozen – Apache

- Buffalo Calf Road Woman – Cheyenne

- Thocmentony/Sarah Winnemucca – Paiute

- Susan La Flesche Picotte – Omaha

- Molly Spotted Elk/Mary Alice Nelson – Penobscot

There are many others who do not appear here because they are more widely known, such as the Yankton Dakota activist, musician, and writer, Zitkala-Sa (l. 1876-1938) or the Cheyenne warrior Mochi ("Buffalo Calf", l. c. 1841-1881). Modern-day figures are also omitted but deserve mention, such as the activist Isabella Aiukli Cornell of the Choctaw nation, who drew national attention in 2018 with her red prom dress designed to call attention to the many missing and murdered indigenous women across North America, and poet/activist Suzan Shown Harjo of the Muscogee/Southern Cheyenne nation. There are many more, like these two, who have devoted themselves to raising awareness of the challenges facing Native Americans and continue the same struggle, in various ways, as the women of the past.

Jigonhsasee (l. c. 1142 or 15th century)

According to Iroquois lore, Jigonhsasee (Jikonhsaseh, Jikonsase) was integral to the origins of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy dated to either the 12th or 15th century. She was an Iroquoian whose home was along the central path used by warriors going to and from battle and became well-known for the hospitality and wise counsel she offered them. The Great Peacemaker (Deganawida) chose her to help him form the Iroquois Confederacy, based on the model of a family living together in one longhouse, and, along with Hiawatha, this vision became a reality. Jigonhsasee became known as the 'Mother of Nations' and established the policy of women choosing the chiefs of the council in the interests of peace, instead of war. The American women's suffrage movement of the 19th century called attention to the freedom and rights of Native American women, notably those of the Iroquois Confederacy, in arguing for those same rights for themselves.

Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617)

Pocahontas is easily the most famous Native American woman, but "Pocahontas" was her childhood nickname (meaning "playful one"), her actual name was Amonute ("gift") and she later took the name Matoaka ("flower between two streams"). Her life, as it is commonly represented, is more legend than truth as epitomized by her relationship with Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631), frequently characterized as romantic. Pocahontas was actually, at most, 12 years old when she met Smith who was then 27, and nothing in the primary sources suggests any deep relationship. It is also unlikely that she saved Smith's life, as he claimed, and more likely she participated in a symbolic ritual he misunderstood. She was the daughter of Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547 to c. 1618), leader of the Powhatan Confederacy, and so made a valuable hostage when she was kidnapped and held for ransom by the colony of Henricus near Jamestown. She would eventually convert to Christianity and marry the tobacco merchant John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622), a union that ended the first of the Powhatan Wars. She died, possibly of tuberculosis, in 1617, returning from a trip to England with her husband and son, Thomas. She is remembered, in the lore of the Mattaponi-Pamunkey nation, as a peacemaker who agreed to marry Rolfe to end the conflict between her people and the English colonists.

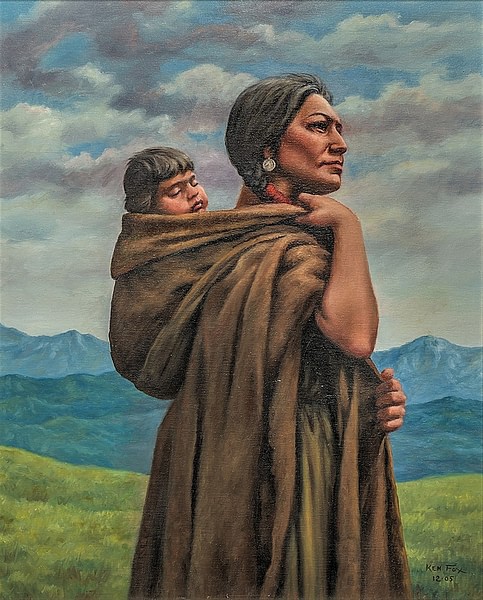

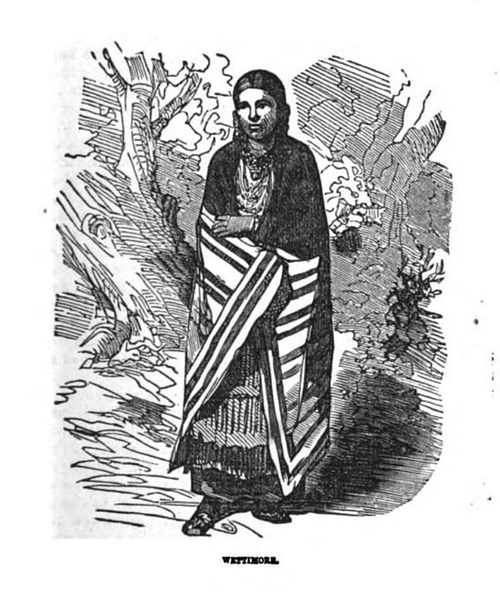

Weetamoo (l. c. 1635-1676)

Weetamoo was a female chief of the Pocasset Wampanoag Nation, wife of Chief Wamsutta (l. c. 1634-1662) of the Wampanoag Confederacy, and sister-in-law of Metacomet (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676). She served as a war chief in King Philip's War (1675-1678) and is best known for the Lancaster Raid of 10 February 1676, during which colonist Mary Rowlandson (l. c. 1637-1711), famous for her later captivity narrative, was taken prisoner. Rowlandson describes her as an impressive figure with a commanding personality who dressed purposefully to convey her standing as an individual of authority. Weetamoo's reputation as a fearless leader became legendary among the colonists and, after her death by drowning, her corpse was beheaded, and the head was placed as a trophy outside of the fort at Taunton, Massachusetts, although they had nothing to do with her death. She is remembered by her people as a great freedom fighter and symbol of resistance to colonial policies of land theft and enslavement of indigenous peoples.

Glory-of-the-Morning (l. c. 1710 to c. 1832)

Glory-of-the-Morning ("Haboguwiga") was the only female chief of the Ho-Chunk/Winnebago nation and also holds the distinction as the first woman to appear in the history of Wisconsin and among the most long-lived in any history. She married the French military commander Sabrevoir de Carrie sometime after c. 1730 and allied her people with the French during the French and Indian War. After Carrie was killed in battle in 1760, Glory-of-the-Morning never remarried and continued to lead her people, negotiating a favorable truce with the British after they won the war. She is said to have lived over 100 years and to have died of natural causes after she was 'called home' by the Thunderbirds, the supernatural entities who presided over her clan, and her children continued her legacy of maintaining a unified nation and advocating of the rights of indigenous peoples.

Sacagawea (l. c. 1788 to c. 1812)

Sacagawea is frequently depicted as the guide and interpreter of the famous Louis & Clark Expedition (1804-1806) but was actually essential to the success of the mission. Her presence among the all-male party allayed the fears of the indigenous peoples they encountered because a war party would not have traveled with a woman, but just as significantly, she saved the journals of Lewis & Clark when the boat they were in capsized on the Missouri River, negotiated for horses with the Shoshone, and provided medical care. She was born a citizen of the Shoshone nation but was kidnapped at around the age of 12 by the Hidatsa and was married against her will to the French explorer and fur merchant Toussaint Charbonneau when she was 13. Charbonneau had himself and his wife hired as guides by Lewis & Clark, and even though she had no choice in the matter, she devoted herself to serving the expedition's goal completely. According to traditional history, she died of an unknown disease around the age of 24 in 1812, but oral tradition maintains she lived longer, returning to her people and dying in 1884.

Old-Lady-Grieves-the-Enemy (l. 19th century)

Old-Lady-Grieves-the-Enemy was a Pawnee woman, not a warrior, who rallied her community to defend the sacred village of Pahaku against a raid by Ponca and Sioux raiding parties. Pahaku (also known as Pahuk, in modern-day Nebraska) was understood by the Pawnee as the most potent of five sacred sites established by the Great Mystery Ti-ra'wa ("Father Above") where the spirit animals lived. The site is famously featured in the Pawnee legend The Boy Who Was Sacrificed, in which a father kills his son, and the boy is restored to life by the animals of Pahaku. At some point unspecified, the Ponca and Sioux attacked Pahaku with such force that the men of a nearby village, who were supposed to protect it, fled and hid. Old-Lady-Grieves-the-Enemy took it upon herself to defend Pahaku, fighting off the raiding parties by herself until her actions shamed the men into joining her and driving off the war parties. Whatever her name may have been prior to this event, she was afterwards known by the one she is famous for. She is celebrated among the Pawnee as a legendary figure symbolizing courage and protection.

Pine Leaf/Woman Chief (l. c. 1806-1858)

Pine Leaf (probably the same person as Woman Chief) was a Crow warrior who became famous for her courage and skill in battle. She was born a member of the Gros Ventres nation but was kidnapped by a Crow raiding party when she was around the age of 10. Raised by the Crow as one of their own, she rejected traditional feminine roles and devoted herself to hunting and warfare, encouraged by her adoptive father who had lost his sons. Her victories over enemy nations elevated her to the status of chief, and she was referred to by Euro-American writers as Woman Chief, but the explorer and fur trader James P. Beckwourth describes this woman by the name Pine Leaf, leading many modern-day scholars to the conclusion that Pine Leaf was also known as Woman Chief. Disdaining 'women's work', she married four women who kept house for her while she raided enemy villages and fended off encroachments by white settlers. Ironically, she was killed in an ambush by a Gros Ventres raiding party, dying at the hands of her own people.

Lozen (l. c. 1840-1889)

Lozen is easily the most famous Native American female warrior that most people have never heard of. Her brother was Victorio (l. c. 1825-1880), chief of the Warm Springs band of Chihenne Chiricahua Apache. When the US government forcibly relocated the band from their ancestral lands in New Mexico to the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona, Victorio broke out and led his people in raids throughout the region. Lozen was understood as a prophet and seer who could locate an enemy's position after reciting prayers and performing a ritual. She was also recognized as a skilled warrior, participating in several battles while also ensuring the safety of the women and children alongside her companion, Dahteste. After her brother's death in battle, she joined Geronimo in his resistance to the United States' genocidal policies and was arrested shortly after his surrender. She was sent to Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama as a prisoner of war and died there of tuberculosis in 1889.

Buffalo Calf Road Woman (l. c. 1844-1879)

Buffalo Calf Road Woman (also known as Brave Woman) was a Cheyenne warrior who became famous for rescuing her brother during the Battle of the Rosebud in 1876. That engagement was afterwards known by the Cheyenne as "The Fight Where the Girl Saved Her Brother" and still is today. Nothing is known of Buffalo Calf Road Woman in her youth, and she is only known for her participation in the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. Nine days after the Battle of the Rosebud, she fought alongside Crazy Horse at the Battle of the Little Bighorn and, according to Cheyenne and Sioux oral tradition, knocked Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer from his horse, forcing him to fight on foot until he was killed. After the Cheyenne surrender in 1877, she was forcibly relocated with her people to "Indian Territory" (Oklahoma) and participated, with her family, in the flight from the reservation known as the Northern Cheyenne Exodus, an attempt to return to their ancestral lands in the north. She died, possibly of tuberculosis, in Montana after her husband had been arrested. When he heard of her death, he hanged himself in his jail cell rather than live without her.

Thocmentony/Sarah Winnemucca (l.c. 1844-1891)

Thocmentony ("Shell Flower") was a Northern Paiute activist, writer, and teacher who was the daughter of the war chief Winnemucca and took the name "Sarah Winnemucca" when she was around the age of 14 and living as a domestic in the home of William Ormsby and his family. She was fluent in English and Spanish, as well as her own language, and became famous for her book Life Among the Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims (1883), the first autobiography written by a Native American woman. She became a popular lecturer, delivering speeches on Native American rights, and established a school in Nevada to preserve and teach the Paiute language and culture. The US government closed the school in 1887, moving the students to state-sponsored boarding schools that encouraged assimilation and the rejection of one's native language and traditions. Sarah Winnemucca continued to advocate for Native American rights until she retired from public life. She died of tuberculosis at her sister's home in Idaho in 1891.

Susan La Flesche Picotte (l. 1865-1915)

Susan La Flesche Picotte was a citizen of the Omaha nation and a social activist and reformer, best known as the first Native American woman to receive a medical degree and practice medicine. She advocated temperance and supported legislation prohibiting the sale and consumption of alcohol as she was aware of the Euro-American practice of taking advantage of Native Americans in land deals by getting them drunk. After receiving her degree, she returned to the Omaha reservation and cared for the community at large, even though her responsibilities were technically limited to the students of the boarding school. She was the sister of the famous journalist, activist, and writer Susette La Flesche (l. c. 1854-1903), best known for her articles on the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, and, like her, was an outspoken advocate for Native American rights – especially those of the Omaha – focusing on temperance, concerns over land transactions, and public health. She died of bone cancer in 1915. Her house in Nevada was preserved to honor her memory and, in 2009, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Susan La Flesche Picotte House.

Molly Spotted Elk/Mary Alice Nelson (l. 1903-1977)

Molly Spotted Elk was a Penobscot actress, dancer, and writer who may have also learned the art of basket weaving from her mother, Philomene Saulis Nelson (l. 1888-1977). Her great-niece is the activist, artist, basket maker, and geologist Theresa Secord (b. 1958). Molly Spotted Elk was her stage name (first given her by the Cheyenne after she was adopted by them). Her given name at birth was Mary Alice Nelson. She began performing traditional Penobscot dances in vaudeville shows at a young age, became an accomplished poet and fiction writer, and lived in Paris, where she continued to perform on stage, between 1931 and 1934, before moving back to the United States and taking up residence in New York. She was constantly challenged by the entertainment industry, which insisted on typecasting her and forcing her to perform in revealing costumes, but she remained true to the traditions of her people in the accuracy of her dance and attire as much as she could. She returned to Paris in 1938 to be with her husband, the French journalist Jean Archambaud but fled when the Nazis invaded in 1940, crossing the Pyrenees Mountains with her daughter into Spain and then returning to the United States. She died of natural causes at the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation in Maine in February 1977.

Conclusion

All of these women, and many others, contributed significantly to the culture and traditions of their people as well as making their mark on national and world history. A list of all the notable Native American women could fill volumes, and have, including the Apache warrior women Gouyene (l. c. 1857-1903) and Dahteste (l. c. 1860-1955), who was also a gifted linguist, and the Cheyenne Ehyophsta (l. c. 1826-1915), who fought with Roman Nose at the Battle of Beecher Island in 1868. Other notables include the Osage prima ballerina Maria Tallchief (l. 1925-2013) and the Ojibwe writers Louise Erdrich and her sister Heid E. Erdrich.

These women are well-known, but there are many others, historically and in the present, who are abducted and murdered and whose names and lives are too often ignored by civil agencies and law enforcement. Native American women in the present day have formed organizations to bring awareness to this problem and to protect women from predators.

Isabella Aiukli Cornell's group, Matriarch, as well as others, such as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) work to call attention to the alarming statistics concerning the disappearance of and violence toward Native American women. The site Native Hope notes:

The National Crime Information Center reports that, in 2016, there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls, though the US Department of Justice's federal missing person database, NamUs, only logged 116 cases. (1)

Greater awareness of the widespread abduction and murder of indigenous women is necessary to help stop it, and the examples of great Native American women can serve as an inspiration. The famous women of the past who fought against the odds for the right to live freely as they wished serve as role models for those in the present seeking simply to live.