The Schweinfurt-Regensburg raids in Germany were a series of attacks by B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator bombers of the United States Air Force in August and October 1943 during the Second World War (1939-45). Schweinfurt had several ball-bearing factories, and Regensburg had Messerschmitt aircraft plants, making both targets crucial to Germany's war effort.

The Combined Bombing Offensive

The commander-in-chief of the British Bomber Command, Arthur Harris (1892-1984), considered small targets like factories too difficult to hit given the technology of the day, and he believed that even if it could be done, it would be necessary to try to do so in daylight. The British Royal Air Force (RAF) had already found out that daylight raids gave too great an advantage to enemy anti-aircraft guns and fighter planes like the Messerschmitt Bf 109. Industrial targets in Germany were beyond the capabilities of an Allied fighter escort at the time, and so the bombers had to fly most of their mission unprotected. The High Command of the USAAF was undeterred by Harris' views and vowed to try a mission of daylight precision bombing.

The strategy of RAF night bombing and USAAF daylight bombing in Europe was known as the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO). Decided at the highest level by the Allied leaders at the Casablanca conference (Codename Symbol) in January 1943, the official objective of the CBO was:

The progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system, and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.

(quoted in Dear, 196)

The Casablanca objective was amended by the Pointblank Directive of June 1943. This emphasised the importance of destroying German fighter plane production in readiness for the D-Day Normandy landings (Operation Overlord) planned for the following summer. Before the Allies could contemplate a land invasion of Continental Europe they had to achieve air superiority. The Quebec conference (Codename Quadrant) of August 1943 reaffirmed the objectives of Casablanca and Pointblank but removed the objective regarding civilian morale. This latter change was perhaps due to the 46,000 civilian deaths that resulted from the first major CBO operation, the bombing of Hamburg (Operation Gomorrah) from 24 July to 2 August 1943. The USAAF was now keen to hit a specific war-industry target.

The Targets

Two targets which fitted precisely with the newly defined CBO objectives of the Combined Chiefs of Staff were Schweinfurt and Regensburg in Bavaria, Germany. Schweinfurt had five factories producing ball bearings, which were crucial to all kinds of weaponry from submarines to tank tracks. Ball bearings were especially important for fighter planes of the German Luftwaffe (Airforce). Regensburg had important Messerschmitt aircraft plants. It was decided to bomb both of these targets in mid-August 1943. The factories had anti-aircraft guns protecting them and could be covered when required by several squadrons of Luftwaffe fighters.

The German Armaments Minister Albert Speer (1905-1981) stated that "As early as September 20 1942, I had warned Hitler that the tank production of Friedrichshafen and the ball bearing facilities in Schweinfurt were crucial to our whole effort. Hitler thereupon, ordered increased anti-aircraft protection for these two cities" (383).

The Bombers

The B-17 Flying Fortress was the best bomber the United States had in the European theatre of WWII. They were flown by the Eighth US Army Air Force (USAAF) which was based in Britain. With four engines, the B-17 was capable of carrying a bomb load of 6,000 lb (2,722 kg) up to a range of 2,000 miles (3,220 km). The aircraft had a crew of ten men and bristled with 13 machine guns of calibre 0.50 inches (12.7 mm) capable of firing at a rate of 800 rounds per minute. It was this unusually large amount of defensive weaponry that led the USAAF commanders to believe they could use bombers in daylight and avoid the losses the RAF had suffered. The other main USAAF bomber was the less well-armed but tried and tested B-24 Liberator.

The August Attack

Schweinfurt and Regensburg were first attacked on 17 August 1943. The plan was to make the attack in two closely timed bomber waves, one for each target, so that enemy fighters might not have time to refuel and rearm when the second wave reached their target. The gap between the two waves was to be about 15 minutes. As it turned out, poor weather in Britain meant the second wave's takeoff was delayed. There were further unexpected delays as the bomber pilots needed more time to gather into formation in the poor visibility offered by the bad weather.

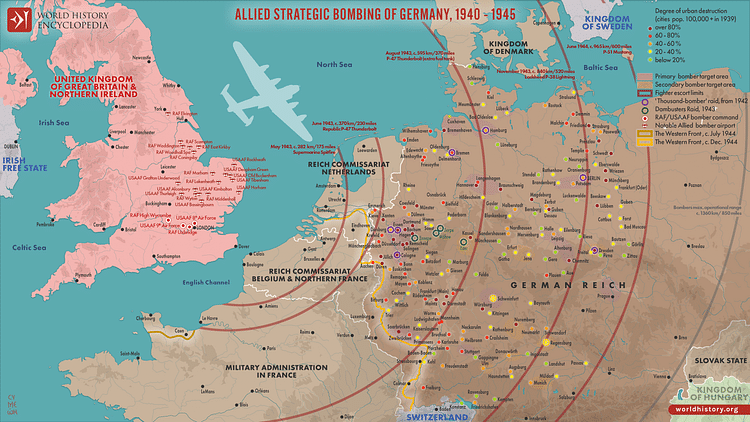

In all, 376 B-17s took off to attack Schweinfurt and Regensburg. The bombers had a fighter escort of P-47 Thunderbolts and P-38 Lightnings, but these only had a range sufficient to reach over Belgium before they had to turn back. When the US fighters left, the bombers were intercepted within a matter of minutes by successive waves of enemy fighters. There was also heavy flak from just about every city the planes flew over. German radar stations and airfields were now fully alert to the fact that there was a large bomber operation underway.

The delay in the second bomber group taking off from Britain meant that this second group flew straight into enemy fighters who were actually waiting to pounce on the first bombers as they came home (although it was planned for the first bomber group to fly on to North Africa for this very reason). The German fighters were not particular which bombers they attacked. Each of the two bomber forces lost at least 10% of their number before they even got to the target. The Regensburg group all dropped their bombs in the target area. The Schweinfurt group was much less accurate, and some loads fell two miles (3.2 km) from the ball-bearing factories. Some of the bombers had been fooled by the Germans using smoke pots into thinking the target had been sufficiently hit, and so they dropped their loads on the nearby town.

For the bomber crews, the return journeys were just as harrowing as the outward runs. Even the bombers headed to North Africa, although largely left alone by fighters, suffered more losses as the earlier flak damage began to play havoc with engines and wings. In the first wave of 146 B-17s, which had set off to bomb Regensburg, 24 were lost. In the second wave of 230 B-17s, which was sent to bomb Schweinfurt, a further 36 bombers were lost. Another 11 bombers which made it back to Britain were so badly damaged they had to be scrapped, and 162 planes suffered minor damage (Neillands, 254).

This loss rate of men and machines was too high to be sustained, but it was realised that the Schweinfurt targets had not suffered nearly as much damage as had been hoped for. Speer recorded that production temporarily fell by 38%. Fortunately for the Allies, the Germans did not move the ball-bearing factories to more inaccessible parts of Germany since this would have held up production for many months. The Eighth Air Force was given a second stab at Schweinfurt.

The Second Schweinfurt Attack

On 14 October 1943, the ball-bearing factories were attacked again. This time, 292 bombers, a mix of B-17s and B-24 Liberators, were deployed. Again, the bombers had a limited fighter escort of P-47 Thunderbolts and P-38 Lightnings. Having got through an attack by enemy fighter planes and negotiated heavy flak from cities he flew over, Pilot Grady Davidson Jr. describes the bombing run he made in his B-17 bomber:

As we started our bomb run we were sitting ducks for the flak and we had to hold a steady straight course and maintain the same altitude in order to align the bombsights. Never have I seen such flak – the black bursts of shells formed a solid black cloud, and the shots were so numerous that it looked like an impossibility to fly a plane through it.

(Neillands, 275)

The bombers were then attacked by fighters on their way out. Again there were heavy losses, 77 bombers in all. Speer records the damage of this second raid:

…all communications were shattered; I could not reach any of the factories. Finally, by enlisting the police, I managed to talk to the foreman of a ball-bearing factory. The oil baths for the bearings had caused serious fires in the machinery workshops; the damage was far worse than after the first attack. This time we had lost 67% of our ball-bearing production.

(391)

Germany could still acquire ball bearings from its army reserves, other German factories (which were not targetted), and suppliers in Sweden and Switzerland, but Speer notes that the effort to obtain these supplies achieved "only slight success" (ibid). Consequently, adaptations were made and, where possible, slide bearings were now used in machinery instead of ball bearings.

The Aftermath

The raids were deemed a partial success by the USAAF in that enemy production was seriously affected, as noted by Speer, but the losses were simply too high, almost double the acceptable 10%. 482 airmen were lost, of which more than 100 were killed in the August raid alone. The figures led to a rethink by the USAAF, and a larger and tighter formation of the B-17 bombers was adopted for future missions. However, similar losses on other raids meant large-scale raids were halted until the arrival of the P-51 Mustang, which, capable of flying at a much longer range than other fighters, was able to escort bombers to and from their targets in Germany.

The Schweinfurt factories were repaired, and double shifts were implemented to make up for the backlog. However, as Speer notes, it had been a close call for Germany:

When you hit Schweinfurt first it was to me like a nightmare getting true, because I was often thinking that bombing one of our bottlenecks of the armament industry would be much more effective than the bombing of cities. And one of the aims I always considered was bombing the ball-bearing industry, and really two attacks on Schweinfurt industry you did much more damage than you ever did before with all the ground bombing. We thought first that we are now at the end of our efforts for armaments industry. But I had a very good representative, Tessler, and he did this all means not only the repair but also the replacement of ball bearings with other devices, which could do the job not as good as the ball bearing but it could be done, and then we found there were stocks in the Army and so stocks could be used too, so we could bridge over the lack of ball bearings for several months until we had repaired the damages. Of course we were frightened that there will be other raids on Schweinfurt and really there were other raids but too late. If you would have repeated those raids shortly afterwards and wouldn't have given us time to rebuild then it would have been a disastrous result.

(Holmes, 431).

As Speer remarked, the raids on Schweinfurt and Regensburg were repeated on 24 and 25 February 1944, this time also involving the RAF. The USAAF sent in 266 B-17s in daylight and the RAF 734 bombers at night. Again, the damage was serious, with Speer noting that ball bearings production sank to just 29% of that before the raids. Speer was amazed but delighted that the Allies did not follow up with one or two more raids as this would have completely finished this vital industry. Part of the reason the Allied commanders held back was the conviction, incorrect as it turned out, that by now, Germany must have established many more alternative ball-bearing factories elsewhere.

The February CBO raids were part of 'Big Week' (Codename Argument), a six-day bombing campaign of multiple targets in Germany, which helped achieve the ultimate objective of establishing Allied air superiority over Europe. Luftwaffe aircraft production was actually increasing in this period, but the most telling effect of the bombing raids was to tempt Luftwaffe fighters into combat with the superior P-51 Mustangs. Ultimately, so many German pilots were killed and Germany's oil supplies so reduced that the Luftwaffe ceased to exist as an operational force.

The RAF did return to bomb Schweinfurt once again in April 1944, but again with heavy losses, around 9% of the bombing force. By the time of D-day on 6 June 1944, the Luftwaffe was reduced to only a handful of planes as the Allies launched a new offensive front. Even towards the end of the war, Schweinfurt remained vital to Germany's future, whatever that might be. When their capture looked imminent, Hitler's specific order to destroy the ball-bearing factories was never carried out in case a miracle should happen and Germany could push back the advancing armies in the East and West.