Childbirth in ancient Rome was considered the main purpose of marriage. Roman girls married in their early teens, and in elite society, some married before they reached puberty. The legal age for marriage was 12 for a girl; 15 was accepted as being an age fit for conception.

The ability to produce a family was also an explicit political concern in Roman society. Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14CE) was particularly troubled by the declining birth rate, especially amongst the upper classes, when he promoted legislation, the Julian Laws in 18 BCE and the Papia-Poppaean Laws in 9 CE, which included measures to promote marriage and reward freeborn women who had more than three children.

Risks & Mortality

There were many risks involved during pregnancy both for mother and child; Pliny the Younger (61 to c. 113 CE) in his Epistulae highlights those risks when he writes of his own young wife, who did not realise that she was pregnant and failed to take certain precautions resulting in her suffering a miscarriage and being gravely ill (8.10). He also writes of the tragedy of two young sisters whom he knew, who both died giving birth (Epist. 4.21.1-3). For any pregnant young girl in labour, physical immaturity could have an adverse effect on the possibility of a normal birth; the remains of a 16-year-old pregnant female discovered in Herculaneum, buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, indicates that this girl may have died anyway struggling to give birth because her immature pelvis was too narrow.

The rates of child mortality at birth or in the first five years of life were high with one in three children dying in their first year, many within the first few weeks. Fronto (95-166 CE), the tutor of Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE), tells of his own personal experience of having lost five children, losing each one separately, each one being born at a time when he bereaved another (1.2 Fronto, To Antoninus Augustus ii. 1-2). To counteract mortality rates, fertility rates needed to be high, a woman in antiquity on average gave birth five or six times as some of those children would not survive. Certainly, the cases of maternal and infant mortality would have varied with the socio-economic classes in Roman society; families in the lower classes had to cope with hardship and poverty, and for the newborn, the risks of infant mortality were compounded by poor diet, poor sanitation, and poor medical knowledge.

Medical Texts

Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) and the physician Soranus of Ephesus (98-138 CE) cover the range of different kinds of maternity care. Pliny in his Historia Naturalis reports primarily on folk medicine; whilst the traditions of folk medicine probably did little to make childbirth safer, these practices were thought to be sound and effective. By contrast, Soranus' Gynaecology, was the first extended treatise on gynaecology and paediatrics in Roman medicine; he wrote with an audience of physicians and midwives in mind.

Both Pliny and Soranus addressed fertility as well as birth control and unwanted births. Soranus in Book I of his treatise notes how absurd it is to make enquiries about the excellent lineage or wealth of a prospective wife but leave unexamined whether the girl will be able to conceive or not and whether she is fit for childbearing; he gives an account of what is required to make such an examination of the girl's ability. He follows this account with a discussion on the problems of timing intercourse to result in conception and then details the stages after a successful conception. Soranus believed that it was only the man and his seed that was responsible for the embryo and that the woman's part was that of a receptacle; his instructions on the care required for the mother-to-be during pregnancy begins with the "protection of the injected seed" (Gyn.1.14.46). He continues his advice on pregnancy with guidance on morning sickness and treatments, exercise, strengthening of the appetite, and supporting the abdomen with broad linen bandages in late pregnancy. Where very young girls were having serious difficulties during pregnancy, Soranus advised a termination to prevent further danger if the uterus was too small and not ready to accommodate complete development.

In Roman society, not everyone actually desired a family, and others may have wished to limit the amount of children in their family. Family planning in Greco-Roman antiquity would have had its difficulties, with much of the offered solutions wrapped up in folklore. Pliny the Elder in his discussion on contraception refers to its necessity for some women who have had many children and are in need of some respite (HN. 29.27.85). Soranus' coverage of the subject in his treatise offers instruction on several methods of birth control such as avoiding intercourse when conceiving is most likely and the use of contraceptives, which include smearing the entrance to the uterus with old olive oil, honey or sap from a cedar or balsam tree or putting a lock of fine wool into the opening of the uterus to prevent conception (Gyn.1.61). Soranus also advises on the procedure for abortion (1.19.60).

Labour & Delivery

In antiquity, pregnancy was measured in lunar months with a baby being born in the tenth lunar month. Midwives were present during labour; men were not present at births unless a doctor was required in case of a high-status mother. Soranus describes the ideal midwife as being free of superstition, highly competent and literate so that she could be knowledgeable (Gyn. 1.2-4). His treatise was illustrated with schemata for the benefit of the medical profession and midwives, showing figures of the foetus in utero and detailing obstetrical care.

The more well-to-do families could afford midwives who were trained according to professionalised obstetrical care. Midwives would routinely encounter complicated births such as the turning of the foetus; Soranus had successfully experimented with this procedure and described it along with other procedures in Book IV, which was devoted to difficult births. Poorer families may not have had midwives so well versed in theory, and when there was no midwife they may have had family members assist in the birth. These families may also have made greater use of Pliny's folk medicine during childbirth in an attempt to relieve the pain and quicken labour; suggested recipes included a drink sprinkled with powdered sow's dung or water mixed with goose semen; whilst these recipes may not have been medically beneficial, the placebo effect may have been effective in bringing comfort.

During labour, a mother-to-be usually lay on a hard, low bed. Cloths soaked in warm olive oil were applied to her abdomen to bring her comfort and a bladder was also filled with warm oil (rather like a present-day hot water bottle) and placed by her side. When it was time to deliver the baby, the pregnant woman was moved to a birthing stool/chair. It was believed that normal delivery was better when the woman was in the upright position, however, if this was not possible due to some difficulty, the mother-to-be would remain on the bed.

The birthing chair had armrests for the woman to grasp during labour, and in the seat of this chair, there was a crescent-shaped hole through which the baby would be delivered by the midwife. Soranus (98-138 CE) recommended that in addition to the midwife, there be three women to assist (Gyn. 2.5). Two of the female assistants stood one at each side of the birthing chair whilst the third stood at the back of the chair gently holding the pregnant woman so that she did not sway with the pains. The midwife sat opposite and below the labouring woman for the delivery. Women from poorer families may have given birth without the use of a stool. Soranus also advised that there should be a second and softer bed, on which the new mother can rest.

In the event that the delivery of the child was not possible, an embryotomy was carried out, that is the removal of the foetus in an attempt to save the life of the mother.

After the Birth

Once the child was delivered, the midwife checked the newborn for any deformities. The father, who held the legal right to expose the newborn child, would then decide whether or not to rear the infant. An unwanted infant might be exposed, that is abandoned. Seneca the Elder (4 BCE to 65 CE) notes in his De Ira that many fathers have the custom of abandoning babies who are weak or deficient in body parts (1.15.2). The infant could also be exposed if it was a female and was seen as more of a financial burden, but male children might be exposed, too, to avoid the costs of raising them or to prevent family property from being divided. Additionally, where the abortion route may have been unwanted, or due to illegitimacy, pregnancy may have been brought to term with the newborn then exposed to die. Exposure, however, did not always mean the death of an infant, it could also include having the unwanted child being raised by others.

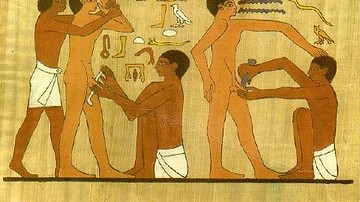

The acceptance of the newborn was indicated by the ritual known as the 'tollere liberos', when the father physically lifted the newborn from the ground and up into the air in a symbolic gesture signalling agreement to raise the baby. The accepted infant was then washed by sprinkling with a moderate amount of fine and powdery salt or natron or aphronitre mixed with whey, olive oil, or juice of barley to make it less drying. The swaddling process followed; clean, soft, and seamless woollen bands were used to wrap the baby limb by limb until the whole body was covered with the arms held at the sides to prevent scratching; the purpose it appears was to control the body and mould the body to the desired shape. The swaddling would be removed daily and infants were given warm baths and massages; instruction on how to carry out these massages is given in some detail by Soranus in Book II, as their purpose was to further help shape the body.

Parents of upper-class Roman children were not usually involved in daily childcare, and although traditional Roman values were very much in favour of the mother feeding her own child, wet nurses were frequently used. It was advised that wet nurses should be between the ages of 20 and 40 years and would have given birth two or three times. Soranus in his postpartum instructions in Book II, advises that in most cases the newborn should abstain from food for two days so that the child might rest after the birth; he notes that the newborn will still be full of maternal food. After two days and before being given breastmilk from the wet nurse, the baby should be given food to lick, such as slightly boiled honey. Referring to the withering of the umbilical cord, he addresses the treatment applied when the umbilical stump drops off, he notes methods used by some women to heal the wound; some burn and grind the ankle bone of a pig or burn and grind a snail and sprinkle over the wound whilst some use lead which has been moulded into the shape of a spinning whorl applying it to the stump, cooling the wound and moulding the stump into a cavity.

Some days after the birth and the tollere liberos, the ritual known as the dies lustricus was performed, which acknowledged the social acceptance of the child. The ritual occurred on the eighth day after the birth of a girl, and the ninth day after the birth of a boy; offerings were made to the gods, and the child was named and welcomed formally into the family by friends and relatives. Parents attempted to protect their children and ward off health problems with the use of apotropaic jewellery, and it is on this day that the bulla, a bauble-shaped gold amulet was given to the infant boy to safeguard him throughout childhood. It is believed that girls were given a similar amulet, known as a lunula. Among the poorer classes, the bulla would have consisted of a knot in a leather thong.

Between the 40th and the 60th day after the birth, Soranus instructs that the swaddling clothes used from birth and that served to give firmness and an undistorted figure can now be removed; the unwrapping of the swaddling began, slowly and gradually a little at a time over a period of days.