Medieval English churches differed in size and layout. Their original and evolving role(s), financial and material resources, and architectural fashions helped determine variability. However, their look ultimately grew from a constant symbiosis between being a place for worship and practical matters. During the 10th-15th centuries, stone construction became firmly established, and that witnessed a golden era of church building.

Purpose & Resources

Immediate, mundane reasons for diversity were just as for any other buildings – houses, castles, offices – it depended on the purpose for which they were originally built and the financial and material resources available to the initial builders and to later owners who wanted to extend and/or beautify it.

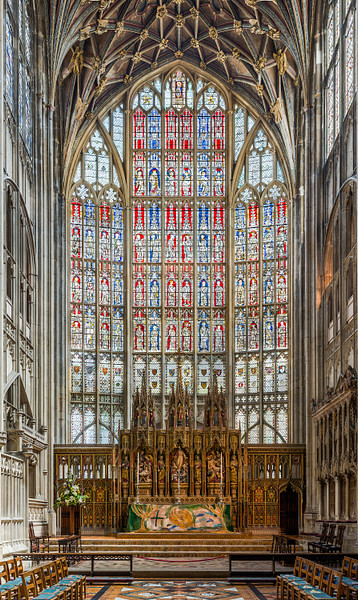

Impoverished communities created basic churches employing the means and materials members of the settlement possessed or could source nearby using their own sweat and skills. Rich sponsors had the wherewithal to envisage and execute the most lavish projects money and authority could buy, transporting materials from far and wide, engaging the leading designers, technology, masons, metalworkers, carpenters, painters, and glaziers of the day.

Basic buildings might be erected as outposts of mother churches/minsters or by individual villages or minor landowners wanting a place, however humble, to express their faith, as a centre for the daily, weekly, and yearly cycles of devotion that dominated and led peoples' lives. They were simple rectangular structures, large enough for maybe 15 to 20 worshippers. The grandest undertakings were sponsored by major royal, aristocratic, or religious order benefactors to produce leading centres of ecclesiastical, administrative, and scholarly influence. Many of the great cathedrals, abbeys, and minsters, like Durham, Lincoln, and Old St Paul's London were wonders of the world at the time they were built, well over 100 meters long, 100 meters high, or more, and tens of meters wide.

Of course, the majority of churches fell in between these extremes. Some might not initially have been conceived on a grand scale, yet over the centuries they grew as patrons and communities responded to changing population sizes and advances in building technology that fed the desire to always have the bigger, better, more beautiful, the latest architectural fashion. In the economic climate of the later Middle Ages, fresh sponsors of church building and extension entered the scene. Newly rich guilds and merchants in many towns employed their wealth to craft ornate chapels or enhance an existing church with which they were associated. From unpretentious origins, many modest buildings thus grew into impressive houses of God – witness Leicestershire's grandest church in Melton Mowbray backed by wool traders' money, and the great wool churches of Norfolk and Suffolk.

Church Growth

Through enhancement, churches grew upwards, adding extra stories and augmented roofs. The tiny windows of Anglo-Saxon and early Norman times yielded to more expansive designs. Improved glass technology meant previously empty windows could now be glazed. Planners produced or heightened towers, sometimes topping them with a spire. They broadened the basic rectangular layout sideways with new aisles parallel to the nave. They incorporated chapels, in or onto the new aisles, to the side of the chancel, maybe a Lady Chapel prolonging the church eastwards behind the sanctuary. More elaborate porches and doorways appeared, possibly an apse added to round off the east end. Beautification and enlargement of the west front was popular, with new façades, maybe a narthex (vestibule). Sometimes the need to replace or shore up a failed wall, window, roof, or tower occasioned modifications.

A law enacted in the 12th century had implications for the general appearance of many churches. The Chancel Repair Regulation made the rector responsible for the upkeep of the chancel and the people of the parish should look after the rest. This could result in a basic chancel if the rector was poor, penny-pinching, or neglected the church and an imposing nave if the community was attentive – or, of course, vice versa.

The Basic Layout

The smallest chapels followed the form of the early churches of Anglo-Saxon times (7th-8th centuries), although historically their precursors reflected much earlier influences from as far away as Ireland, the Rhineland, Italy, Greece/Byzantium, and Egypt. Churches then followed predominantly a simple rectangular layout. Round churches were/are extremely rare.

At first basic churches might consist of a single cell – one undifferentiated area shared by the congregation and the priest. Gradually the space grew and split into a two-cell format, with room for the congregation (the nave) plus a separate area (the sanctuary) reserved for the celebrant. It housed the altar where rituals were enacted. The sanctuary could be further segmented into the quire, the area before the altar, and the sanctuary (or presbytery, where the presbyter, the elder, priest officiated), the holiest spot, typically elevated at the top of some steps. The joint area of the quire and the sanctuary is often termed the chancel.

Importantly, this bi- or tri-partite division continued as the core plan that all churches conformed to, certainly until the Reformation, discernible even in the grandest buildings. Lesser churches after they began to accrue all their extra appendages and branched out sideways, upwards, and lengthways to become the more complex creations of the 11th-16th centuries still maintained this basic formation.

Progressions & Thresholds

Although nowadays we are used to seeing churches hemmed in by other buildings and roads, especially in towns, originally they were the focal point in a wider sacred setting. The progression in a church from the nave, the common space for all believers, to the chancel, generally reserved for the priest, then within the chancel the sanctuary, reserved exclusively for ordained clergy and the utensils to conduct the most sacred rites at the altar, formed only the latter stages of a longer journey from the earthly to the divine.

Churches were surrounded by hallowed land, marked off from earthly, unconsecrated ground by a perimeter mound, hedge, fence, or wall. It may also contain shrines and paths for processing. Here believers were buried. Non-believers, people expelled from the church and those who in some way had offended God, through murder or similar sinful acts, were not permitted burial in a sanctified spot. For churches with cemeteries, the main threshold between the unhallowed and hallowed ground was the lych-gate (lych/lic/lyke was Anglo-Saxon for "corpse"), the entrance where the body of the departed rested, waiting for the welcome blessing from the priest before proceeding into church for the continuation of the journey into the afterlife.

At the church portal, there was a stoup, a carved basin containing holy water. Those entering church dipped their finger in and blessed themselves with the sign of the cross, recalling the holy water and sign of the cross they received at baptism and acknowledging the crossing of another threshold into an even holier space. Stoups remain visible in some older churches (and modern Roman Catholic churches), but iconoclasts at the Reformation hacked off most of them as symbols of superstition not supported by biblical precedent.

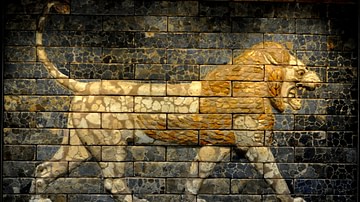

This progression from the worldly to the holiest of holies was not a trait confined to Christian churches. The Bible (e.g. 1 Kings, chapter 6 detailing Solomon's great temple) describes Jewish temples with their outermost precinct followed by antechambers where people assembled for worship. From there, the progression was to the more holy inner courts where priests performed, and finally to the holiest of holies, with access restricted to the highest priests, like the Christian chancel partitioned off with veils or screens, and like the Christian high altar a spiritual threshold between heaven and earth.

Roman temples, Celtic sacred groves (nemeta), the Scandinavian hof and Anglo-Saxon hearg(as) (sacred plots) likewise comprised a perimeter structure marking off a wider field of hallowed ground where courts, festivals, and other general meetings took place. This surrounded or led onto successively more sacred spaces, to quarters reserved for the actions of the highest in the priestly hierarchy.

Monastic Shapes

Although the layout of the church component of monastic institutions reiterated the basic two- or three-cell pattern of parish churches, they constituted a different class of establishment in so far as monks and nuns lived, ate, slept, worked, and studied there. This necessitated refectories, kitchens, dormitories, and lavatories, together with libraries, workshops, breweries, barns, stables, and so forth, linked to their occupations and industry. Many provided almshouses and hospitals to fulfil the obligation of clergy to care for the poor and infirm. Libraries, study areas, and dormitories were often juxtaposed directly onto the church, with connecting passages that enabled the monks and nuns to slip easily from their beds, desks, and meals to attend to their strict routine of devotions in church throughout the day and night.

A medieval monastery could accumulate appreciable wealth, from tithe revenues, farming, trading, and other wheeler-dealing. For some being a place of pilgrimage swelled income. They used this wealth to expand, not only by amplifying and embellishing the central church building where divine office took place but also by developing the outer structures.

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547), most of these extra buildings were demolished or left to tumble down. Some were turned into stately homes, with their foundations and materials incorporated into the new building. However, some former abbeys became cathedrals, where vestiges of monastic living, working, and study buildings remain visible. Amongst others, Hereford has its library, Gloucester Cathedral has its cloisters, and Lincoln retains its chapter house.

In the layout of Salisbury Cathedral, the monastic cloisters and the chapter house are clearly visible. Such buildings can also be seen amongst the ruins of some former abbeys – Fountains abbey provides a particularly splendid example. Present-day parish churches that were previously monasteries likewise often evidence anomalies of layout and structure that betray their more magnificent past. A panel on the south wall of the now small church in Owston (Leicestershire) represents a clue to the former cloisters and the thickness of the walls and anomalous massive free-standing pier that supports the south arcade hint at its erstwhile scale.

Deeper Reasons for Diversity

The effects of purpose and envisaged grandeur, available finance, and material resources partially explain why churches look like they do. The drive to establish more splendid and imposing places of worship also had cultural-political roots.

In Anglo-Saxon times, founders erected impressive structures to emphasize the superiority and potency of Christianity and its holy places over pre-Christian holy sites and idols. Indeed, to underline this point many early churches appropriated locations of earlier, pre-Christian worship. Further, after the Norman conquest of England rulers as Norman rulers supplanted the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy and landowners in the 11th-12th centuries, they too had a point to prove. Vanquished Anglo-Saxon ways were finished, a new power held sway. To drive this home the occupying Normans demolished Anglo-Saxon churches or radically modified them according to the styles they brought with them. Ecclesiastical and architectural ascendency became weapons and symbols of cultural and administrative hegemony.

More locally, church-building and boasting the biggest and best played out in turf wars between magnates. Planting a superlative church was one method of staking a claim to a territory. It also signalled to the local population which earthly lord they ought to show tribute to. The founding by the Earl of Leicester of Garendon Abbey and Ulverscroft Priory in the 1130s to stifle the ambitions of the Earl of Chester and his encroachment on Leicestershire territory is just one of countless examples of this.

Whilst such earthly factors did drive the compulsion to build bigger and better churches, these ultimately were influenced or trumped by deeper reasons for celebrating beauty. To begin with, spires, towers, and windows were not the foremost vehicles for the expression of belief and devotion. They served largely functional ends. Windows admitted light, roofs kept out the rain. Towers housed bells, which summoned to prayer, and in certain areas at certain times doubled as watchtowers and refuges if the community was under threat. Churches, though, were always consecrated and dedicated to God. They were places of worship. People realised that a church's visual impact could also proclaim this true purpose and the longing for veneration and prayer.

In this way, aspects of design became imbued with the symbolism of belief and worship. People imagined the higher the towers the closer to God they stretched. Spires pointed heavenwards. The larger the windows the more the light of Christ flooded in. More ornate designs and decorations were witness to the gifts God granted to man and celebrated His inspiration. More austere designs (e.g. the Early English architectural style of the 13th century) professed humility before Christ, a shunning of worldly riches, and hope for sumptuous rewards in heaven.

Cleansing Souls

There were further reasons that motivated expressions of ever deeper faith. Medieval church teaching and belief stated that good works on earth might mean not only more favour from God in life but also crucially greater likelihood of attaining heaven in the afterlife. Hence the ambition to create structures ever more pleasing to God. Even in poor chapels local craftspeople fashioned carvings and paintings to the best of their ability and resources so that God might smile upon them.

Furthermore, medieval people believed that after death, depending on one's record in life, one would proceed to heaven or hell. Few were likely to be so perfect that they achieved immediate access to heaven. Most would have to wait in purgatory (from the Latin purgare, "to cleanse") whilst their souls were cleansed prior to their journey onwards. Apart from sponsoring churches and creating exquisite works of sacred art another way to pave one's way to heaven was through having people pray for one's soul.

This accounts for the spread of chantry chapels and sub-altars in churches. The well-off hired priests to chant (hence 'chantry') masses and say prayers there to smooth their path through purgatory and onto heaven. Individuals funded masses not just for themselves and their families whilst they were alive but also for themselves, their ancestors, and their descendants in perpetuity after they died. Lesser merchants and tradespeople could not afford this luxury. One role of guilds was to sponsor sub-altars or chapels and priests to make available to ordinary workers and their families the privileges and insurances through prayers and masses otherwise open only to the rich.

There was a further driver. Most Franco-Norman landowners who wielded power in the 11th-13th centuries amassed their wealth through war, subjugation, and assorted underhand means. Their bishops admonished them for this, warning that they risked eternal damnation for their iniquities. However, they simultaneously offered a get-out clause. By employing their wealth to benign ends some of their sins might be absolved and torment in the afterlife avoided or ameliorated. The belief was that the more grand and lavishly appointed the church, hospital, or almshouse, the more one's wrongs could be assuaged.

Countless other aspects of church fittings and furniture celebrated the sacredness of the building and pointed the way to salvation. Frescoes on the walls, depictions in the stained glass, statues, paintings, icons and symbols on lecterns and fonts, or the raised high altar all contributed. An elucidation of these is beyond the confines of this article, but two further aspects of why churches look like they do bear mention.

Orientation

Christian churches generally face east and the high altar is situated at that end. Some speculate this is because they face the Holy Land of Christ's birth. That is probably not the reason, in so far as not all point eastwards, and in countries where they would need to point south, west, or north to face the Holy Land, they still predominantly orient east. The more likely explanation is that they greet the rising sun, God's light for the world, the source of life. The west was seen more as a place of darkness. It was no accident that anciently the narthex where the uninitiated waited for baptism, to walk into the light of Christ, was situated at the west end and the font where they were baptised stood inside the western threshold.

Numerous churches have a cross-shaped layout. The nave and chancel form the upright and the transepts are the crossbar. Many surmise this configuration stems from churches wanting to recall the cross on which Christ died. Whilst people may feel this, and like the idea of spires rising heavenwards it adds a dimension to the ways in which churches may reflect belief, more probably the crucifix shape derives from advances in church building in the later Middle Ages. Soaring central towers and spires and elaborate, heavily vaulted ceilings required massive supports beneath them to avoid collapse. They also demanded bolstering laterally to prevent them from splaying outwards. Transepts performed this role.

Conclusion

Although the comments above relate predominantly to churches in England between the 8th-16th centuries the same sources of diversity apply across many countries, even if that diversity is articulated in varying styles. Today the appearance of new churches continues to reflect these influences, a combination of the effects of resources available and how people wish to see their faith expressed.