The Battle of Cowpens (17 January 1781) was a decisive battle in the southern theater of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). It saw a detachment of Continental soldiers and Patriot militia under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan defeat a British force under Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton. The battle helped lead to the end of British domination in the American South.

Background

On 2 December 1780, Major General Nathanael Greene rode into the American military camp at Charlotte, North Carolina. A 38-year-old Quaker from Rhode Island, Greene had been entrusted by General George Washington to take charge of the remnants of the Southern Department of the Continental Army after its disastrous defeat at the Battle of Camden (16 August 1780). What Greene found at Charlotte was less an army than a rugged gathering of 1,400 disheartened men. The troops were undersupplied, underfed, and lacked clothing. Several men sat huddled around the campfires practically naked, with only rags or blankets to protect them from the elements. Many of the soldiers stirred themselves only to plunder the surrounding countryside for food, and the officers had grown jaded enough not to care. It was a ghastly display of dejection that must have reminded Greene of the state of the main army at Valley Forge three winters before.

It was not hard to see why the army was in such a depressed state. The Americans had suffered nothing but defeat since the British had first invaded the American South in late 1778. Having grown frustrated with their unsatisfactory military campaigns in the North, the British had shifted their focus to the South, which was rumored to be replete with Loyalists as well as the source of much of the United States' commercial wealth. The capture of the South, it was believed, would not only cut the United States in two but also cripple its ability to keep fighting. The British implemented their so-called 'southern strategy' in December 1778 by seizing Savannah, Georgia; the following year, a Franco-American attempt to retake the city failed, and Georgia became the first state to fall back under British control. In May 1780, the British won the Siege of Charleston, taking the largest and most important city in the entire South. Under the command of Lord Charles Cornwallis, the British then set about pacifying the rest of South Carolina. This sparked a bloody regional civil war, as the state's Patriot and Loyalist militias brutalized one another in the South Carolina backcountry. The southern Continental Army, under General Horatio Gates, had tried to retake the state but had been decisively defeated at Camden.

Now, as Greene took over command of the depleted army from Gates, he realized the monumental task that rested upon his shoulders. Should he fail, there would be nothing to prevent Cornwallis from conquering North Carolina and Virginia, completing the British 'southern strategy'. Greene was a cautious commander who pursued a 'Fabian strategy'. That is, he tried to avoid fighting any pitched battle that he was not sure he could win, instead wearing the enemy down through attrition and guerilla fighting, striking only when he spotted vulnerability. The Patriot militias already operating in South Carolina could serve this purpose well; Greene hoped that they could keep the British distracted long enough for him to whip his army into shape and maybe find new recruits. However, he would need someone he could rely on to go down into South Carolina and keep the militias supplied and organized. As it happened, Greene already had just the man in mind.

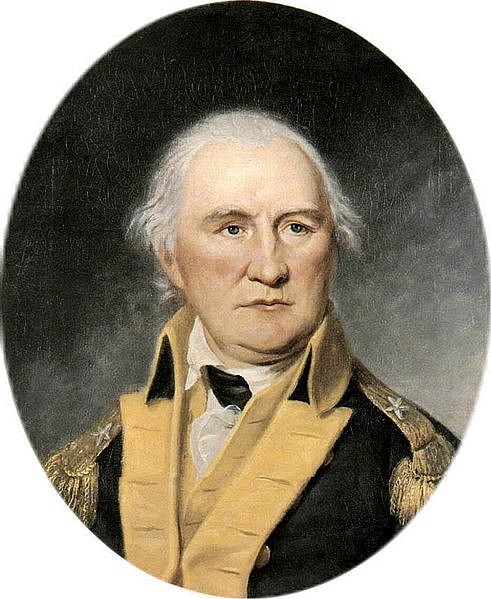

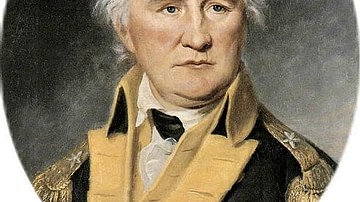

The Old Wagoneer

Daniel Morgan was a rough-and-tumble frontiersman, who had already become something of an American legend. During the French and Indian War, he had served as a wagon driver for the British army but was constantly getting into trouble; after an altercation in which he pushed down a British officer, Morgan had been sentenced to 500 lashes upon the back. Such a punishment was often fatal, but Morgan bore it without losing consciousness, even counting along with the drummer inflicting the lashes. The ordeal left Morgan with both a permanently scarred back and a lifelong hatred for British officers. At the start of the Revolutionary War, he had been selected to command a corps of riflemen and had fought with distinction in both the American invasion of Quebec (1775) and the Battles of Saratoga (1777). Now a brigadier general, he was beloved by his men, who affectionately referred to him as the 'Old Wagoneer'.

Morgan's folksy charisma and commitment to the Patriot cause made him the perfect candidate to go into South Carolina and stir up trouble. Greene had made the risky decision to split his already small army in half. This was partly because there were not enough provisions around Charlotte to supply all 1,400 men but also because Greene needed to buy time to strengthen the weaker part of his army. The plan was for General Morgan to take the 600 most experienced men into the Catawba region of South Carolina where he could harass British supply lines, provide aid to the Patriot militias operating in the area, and otherwise disrupt British operations. Greene, meanwhile, would remain in North Carolina to train the weaker half of his army for the upcoming campaign season.

Morgan dutifully set off as instructed, arriving on the Pacolet River in South Carolina on Christmas Day. Here, he was joined by Andrew Pickens, one of the partisan leaders who had been waging guerilla warfare in the South Carolina backcountry. Pickens brought 60 hardy militiamen and assurances that more were on their way. Morgan and Pickens, however, would have less time to get situated than they would have liked. By 2 January 1781, Cornwallis had learned of their presence in the state and decided to deal with them before they became a larger threat. Aware of Daniel Morgan's rugged reputation, Cornwallis dispatched a man who equaled him in energy and exceeded him in infamy, Banastre Tarleton.

Cat & Mouse

Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton was only 26 years old but had already established himself as an aggressive, energetic, and ruthless officer. Half a year before, at the Battle of Waxhaws, his men had massacred scores of Patriot soldiers as they were attempting to surrender; Tarleton, who had fallen from his horse just before the alleged slaughter, claimed that he had lost control of his men and forever denied any responsibility. Whatever the truth of the incident, Waxhaws remained a stain on Tarleton's reputation, earning him notoriety as 'Bloody Ban'. Cornwallis was undoubtedly pleased to use Tarleton's black reputation to his advantage, sending him out like a mad dog whenever he wanted to inspire fear in the Patriots.

And so, Tarleton set out, riding hard for the vicinity of the Pacolet River, the last known location of Morgan's tiny force. Riding at his heels were the green-coated dragoons of the British Legion, an elite unit of Loyalists with as bloodthirsty a reputation as their colonel. Morgan soon received word that Tarleton was rapidly approaching his location and did the sensible thing for a military commander in his position – he ran. Morgan began moving back north, toward the North Carolina border, but he found that he was slowed down by his supply wagons. By contrast, Tarleton was traveling light and was gaining ground every day. Eventually, Morgan decided it was better to turn and fight rather than risk being overtaken.

On 16 January 1781, he moved his army to the open meadow of Hannah's Cowpens, a popular spot for local farmers to take their cattle to graze. The field was 500 yards (457 m) in length and width, with precious few trees to hide behind – a tremendous advantage to Tarleton, whose force consisted of around 500 cavalry. Sitting out in the open, Morgan's men could easily be outflanked. Additionally, the Broad River flowed behind the Patriots, cutting off their route of retreat. Despite these deficiencies, Morgan was convinced that this was the perfect battleground for his purposes. "On this ground," he told his nervous officers, "I will beat Benny Tarleton or I will lay my bones" (Fleming, 188).

Morgan's Preparations

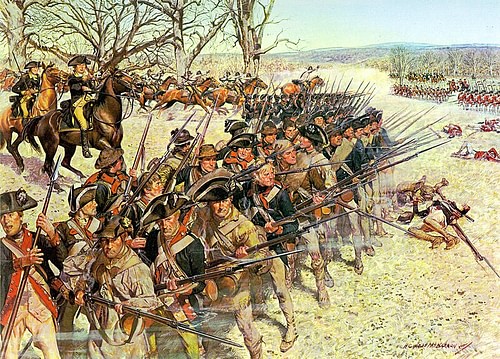

Morgan knew that Cowpens was not an ideal battlefield, a fact that he would use to his advantage. Tarleton was well-known to be an aggressive commander, almost to the point of recklessness. Morgan was willing to bet that the sight of the Patriot army sitting out in the open, vulnerable, would be too much for 'Bloody Ban' to resist; Morgan gambled that Tarleton would charge straight into the Patriot army, thereby falling straight into a trap. This trap, which Morgan hoped would result in a double envelopment of the British troops, would require three separate lines of defense: the first line would consist of skirmishers, the second of militia, and the third of Continentals (or regular soldiers).

For the first line, Morgan personally selected 150 of his best riflemen. They were told to aim for the officers to render the advancing British soldiers leaderless before retreating back behind the second line. The second line, consisting of 300 militia under Andrew Pickens, was ordered to fire two volleys and then also fall back in a feigned retreat; the British, assuming that the militia were fleeing, would continue to push forward. Once the British charge made it to the third line, consisting of Continentals from Maryland and Delaware, the militia would rejoin the battle and attack the British left flank. At the same moment, the American cavalry, led by Lt. Colonel William Washington (a second cousin to the general) would emerge from behind a nearby hill and attack the other flank. The British would find themselves surrounded.

Morgan was certainly taking a risk; at the Battle of Camden, the militia had broken and fled almost as soon as the fighting had started, leaving the Continentals to be surrounded and destroyed. But Morgan was confident that they could get off at least two volleys. And besides, with the Broad River at their backs, there was nowhere to run to this time. As night fell, General Morgan went from campfire to campfire, talking and joking with the men. His laidback demeanor put them at ease, taking their minds off the battle to come.

The Battle

Hours before dawn, one of Morgan's scouts spotted the green-coated dragoons of Tarleton's vanguard trotting up the Green River Road toward the Cowpens. The scout raced back to inform the general who, in turn, woke his men by shouting, "Boys, get up! Benny's coming!" (Fleming, 199). The Patriots were in position, all according to Morgan's plan, by the time the British arrived on the field a few minutes before sunrise. Tarleton had around 1,100 men, slightly outnumbering Morgan's 1,065-man force. When he noticed that Morgan's army was sitting in an open field, Tarleton smelled blood. His line had barely even formed up when he ordered it forward – just as Morgan had anticipated. As soon as the British troops came within range, Morgan's skirmishers opened fire, cutting down 15 British dragoons in mere minutes. The skirmishers then targeted the officers, picking them out by their resplendent scarlet coats, before running back behind the second line of militia. The first part of Morgan's plan had been a success.

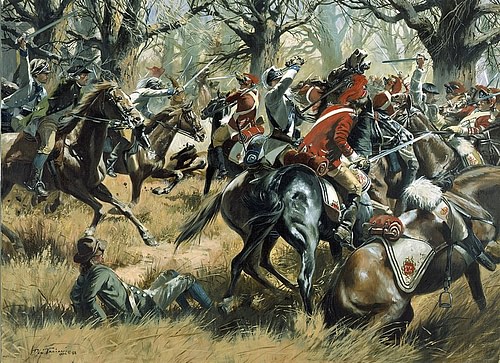

Pickens knew that he only had two shots and was determined to make the best of them. He had his men hold their fire until the British came within a 'killing distance' of 50 yards (45 m). Once they came within this range, Pickens yelled for them to fire; the crackle of muskets sounded down his line, as several British and Loyalist soldiers crumpled to the ground. The British line hesitated, undoubtedly shocked to have received such resistance from mere militia. But this hesitation was only momentary, and before long the British line continued its well-disciplined march, bayonets glistening in the early morning sun. Pickens shouted for his men to reload, which most of them managed to do. They fired off a second, even more devastating volley before turning and running for their lives. Tarleton's dragoons caught up with the militia on the right-hand side and were soon amongst them, their sabers hacking and slashing at the panicked men below. Colonel Washington noticed and led his cavalry forward, chasing the dragoons off and giving the militia a chance to escape.

The militia ran behind the third line, stopping to regroup as planned. The British, who were depleted of officers and disorientated from nearly an hour of fighting, once more took the bait. They charged onward and ran straight into the third and final Patriot line – this was the one that consisted of the Maryland and Delaware Continentals, under the command of General John Eager Howard. Once again, Howard waited for the British to come within 50 yards before ordering his troops to fire off a volley, causing the British line to waver. Tarleton, watching from afar, believed that he only needed one final push to break the American line and committed his reserves – the 71st Highland Regiment of Foot. The Highlanders swarmed forward, the air filling with the sound of bagpipes as they approached the American right flank. Realizing he was about to be outflanked, Howard ordered the Virginia militia on his right to turn and face the oncoming Scotsmen. But the militia misunderstood his orders and started to withdraw.

Morgan noticed the fleeing militia and rushed forward, yelling at them to turn around. The militia dutifully stopped, turned, and unleashed a murderous volley into the oncoming Highlanders. Howard then shouted for his men to fix bayonets, and the Continentals rushed forward, charging into the tired British troops. It was at this moment that Pickens' militia rejoined the battle, striking the left of the British flank. At the same time, Washington's cavalry, which had just returned from chasing off the dragoons, slammed into the right and rear of the British line. The British and Loyalists were surrounded. Within minutes, they began to throw down their weapons; the elite Highlanders held out for a while longer but soon realized it was all over and surrendered. The Americans then rushed forward to Tarleton's two cannons (known as 'grasshoppers' because of the way they jumped when fired). After savage hand-to-hand combat with the artillerymen, the Americans captured the grasshoppers.

Even as he watched his army unravel before his eyes, Tarleton was not ready to give up. He called up the last of his reserves, the cavalry of his own British Legion, and led them in a spirited charge to retake the cannons. Colonel Washington noticed this maneuver and led his cavalry forward to intercept, leading to a climactic cavalry fight amongst the grasshoppers. Washington singled Tarleton out and charged at him, in the process becoming isolated from his men. Tarleton and two officers swiveled around to meet the attack; during the melee, Washington's saber broke at the hilt, and one of the British officers stood in his stirrups to deliver a killing blow. Just then, the officer was struck by a bullet; it had been fired by Washington's 14-year-old Black bugler, who saved the colonel's life. Tarleton fired two pistol shots, one of which wounded Washington's horse, allowing Tarleton and his small band of survivors to escape. After changing horses, Washington pursued, chasing Tarleton for 16 miles (25 km) before giving up.

Aftermath

The battle was over by 8 a.m., after about an hour of fighting. The British had lost 100 killed and over 800 captured (229 of whom had also been wounded), a casualty rate that effectively annihilated Tarleton's force. The Patriots had lost 25 killed and 124 wounded. It was a resounding victory for the Patriots, but Morgan knew he could not waste much time celebrating, as Cornwallis' main army was nearby and would soon be desiring vengeance. Leaving the wounded with Andrew Pickens under a white flag of truce, Morgan packed up the rest of his army and marched back to the relative safety of the Catawba River, which he reached on 23 January. Before long, he slipped back into North Carolina and linked up with General Greene, whose army was in a much better condition than it had been the month before.

Tarleton, meanwhile, had ridden back to the British camp in disgrace. He delivered his report of the battle to Lord Cornwallis, who decided that they would march into North Carolina to go after Morgan and Greene. He chased Greene across the state of North Carolina before the two armies finally clashed at the Battle of Guilford Court House (15 March 1781). Tactically, this resulted in a British victory, although Cornwallis ended up losing around 25% of his army; in a truly Fabian fashion, however, Greene managed to extricate his own army. The frustrated Cornwallis decided to abandon the Carolinas altogether and march into Virginia, where he was ultimately defeated at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781).

The Battle of Cowpens, therefore, can rightfully be regarded as a major turning point in the war. It redeemed the reputation of the Patriot militia after Camden and was the finest moment for Morgan, whose innovative double envelopment strategy has been likened to a miniature version of Hannibal's maneuver at the Battle of Cannae. More importantly, the battle was the major factor that convinced Cornwallis to abandon South Carolina in pursuit of Greene, thereby ending British domination of the state and sending Cornwallis on the trajectory toward Yorktown and defeat. The battle arguably saved the South from falling to the British and allowed for the final American victory to occur ten months later.