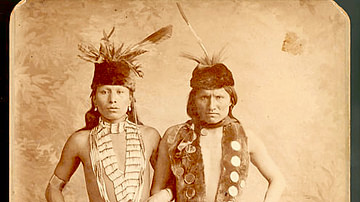

Black Elk (l. 1863-1950) of the Oglala Lakota Sioux was twelve years old at the Battle of the Little Bighorn on 25 June 1876. He gives his account of the famous conflict in the work Black Elk Speaks (1932), and, even at a distance from the event, his memory is supported by earlier narratives.

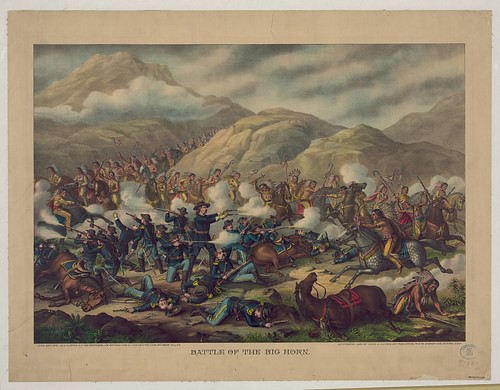

The Battle of the Little Bighorn (also known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass/Fight of the Greasy Grass, 25-26 June 1876) is the most famous engagement of the Great Sioux War (1876-1877) and is commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand as the Civil War hero and Indian fighter Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) was defeated and killed there by opposing forces led by Sioux warriors Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877) and Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890). The engagement was a decisive victory for the Sioux but would be their last in the war as, afterwards, the US military sought retaliation.

Black Elk would be 13 on 1 December of 1876, but, according to his own account, he was still considered a "boy" in June of 1876 as he had not yet faced an enemy in battle or taken his first scalp. This would all change at the Battle of the Little Bighorn when he was forced to engage with the hostile forces of the US military and was commanded by an older warrior to take an enemy's scalp.

His narrative of the chaos and confusion of the battle, given to the American poet and writer John G. Neihardt (l. 1881-1973) in 1932, is supported by the account given by the Sioux warrior Rain-in-the-Face (l. c. 1835-1905) to the Sioux physician and author Charles A. Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa, l. 1858-1939) as given in Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains (1916). Rain-in-the-Face, according to Eastman's account, notes:

In that fight, the excitement was so great that we scarcely recognized our nearest friends! Everything was done like lightning. (137)

This version of the battle is also given by others, including the Northern Cheyenne warrior Wooden Leg (l. c. 1858-1940) and Sioux war chief Gall (l.c. 1840-1894). Gall is referenced by Black Elk below in rallying the warriors against the charge of Major Marcus Reno (l. 1834-1889), who was the first to assault the camp of the Sioux and their Cheyenne-Arapaho allies on 25 June 1876.

The significance of Black Elk's account, aside from what it has to say about the confusion of the battle, is widely recognized as an accurate depiction of how the Plains Indians, specifically the Sioux, felt about the westward expansion of the United States onto their ancestral lands. The Sioux, as Black Elk says, regarded the lands as theirs, not only according to their own traditions but through the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, and yet the soldiers of the US government kept coming to attack and drive them from it.

Text

The following passage comes from Black Elk Speaks, pp. 65-70, from the 2014 Bison Books edition of the work. The first two paragraphs reference the Battle of the Rosebud (17 June 1876) and the Battle of Powder River (17 March 1876), the latter recognized as the first engagement of the Great Sioux War.

Crazy Horse whipped Three Stars [General Crook] on the Rosebud that day, and I think he could have rubbed the soldiers out there. He could have called many more warriors from the villages, and he could have rubbed the soldiers out at daybreak, for they camped there in the dark after the fight.

He whipped the cavalry of Three Stars when they attacked his village on the Powder River that cold morning in the Moon of the Snowblind [March]. Then he moved farther west to the Rosebud; and when the soldiers came to kill us there, he whipped them and made them go back. Then he moved farther west to the valley of the Greasy Grass [Little Bighorn]. We were in our own country all the time and we only wanted to be let alone. The soldiers came there to kill us, and many got rubbed out. It was our country, and we did not want to have trouble.

We camped there in the valley along the south side of the Greasy Grass before the sun was straight above; and this was, I think, two days before the battle. It was a very big village, and you could hardly count the teepees. Farthest up the stream toward the south were the Hunkpapa and the Oglala were next. Then came the Miniconjou, the San Arcs, the Blackfeet, the Shyelas; and last, the farthest toward the north, were the Santee and Yankton. Along the side towards the east was the Greasy Grass, with some timber along it, and it was running full from the melting snow in the Bighorn Mountains. If you stood on a hill, you could see the mountains off to the south and west. On the other side of the river, there were bluffs and hills beyond. Some gullies came down through the bluffs. On the westward side of us were lower hills, and there we grazed our ponies and guarded them. There were so many they could not be counted.

There was a man by the name of Rattling Hawk who was shot through the hip in the fight on the Rosebud, and people thought he could not get well. But there was a medicine man by the name of Hairy Chin who cured him.

The day before the battle, I had greased myself and was going to swim with some boys when Hairy Chin called me over to Rattling Hawk's teepee and told me he wanted me to help him. There were five other boys there and he needed us for bears in the curing ceremony because he had his power from a dream of the bear. He painted my body yellow, and my face too, and put a black stripe on either side of my nose from the eyes down. Then he tied my hair up to look like bear's ears and put some eagle feathers on my head.

While he was doing this, I thought of my vision, and suddenly I seemed to be lifted clear off the ground; and while I was that way, I knew more things than I could tell, and I felt sure something terrible was going to happen in a short time. I was frightened.

The other boys were painted all red and had real bear's ears on their heads.

Hairy Chin, who wore a real bear skin with the head on it, began to sing a song that went like this:

"At the doorway, the sacred herbs are rejoicing."

And while he sang, two girls came in and stood one on either side of the wounded man; one had a cup of water and one some kind of herb. I tried to see if the cup had all the sky in it, as it was in my vision, but I could not see it. They gave the cup and the herb to Rattling Hawk while Hairy Chin was singing. Then they gave him a red cane and, right away, he stood up with it.

The girls then started out of the teepee, and the wounded man followed, leaning on the sacred red stick; and we boys, who were the little bears, had to jump around him and make growling noises toward the man. And, when we did this, you could see something like feathers of all colors coming out of our mouths. Then Hairy Chin came out on all fours, and he looked just like a bear to me. Then Rattling Hawk began to walk better. He was not able to fight the next day, but he got well in a little while.

After the ceremony, we boys went swimming to wash the paint off, and when we got back, the people were dancing and having kill talks all over the village, remembering brave deeds done in the fight with Three Stars on the Rosebud.

When it was about sundown, we boys had to bring the ponies in close, and when this was done it was dark and the people were still dancing around fires all over the village. We boys went around from one dance to another, until we got too sleepy to stay up anymore.

My father woke me at daybreak and told me to go with him to take our horses out to graze and, when we were out there, he said, "We must have a long rope on one of them so that it will be easy to catch; then we can get the others. If anything happens, you must bring the horses back as fast as you can – and keep your eyes on the camp."

Several of us boys watched our horses together until the sun was straight above and it was getting very hot. Then we thought we would go swimming, and my cousin said he would stay with our horses till we got back. When I was greasing myself, I did not feel well; I felt queer. It seemed that something terrible was going to happen. But I went with the boys anyway. Many people were in the water now and many of the women were out west of the village digging turnips. We had been in the water quite a while when my cousin came down there with the horses to give them a drink, for it was very hot now.

Just then we heard the crier shouting in the Hunkpapa camp, which was not very far from us, "The chargers are coming! They are charging! The chargers are coming!" Then the crier of the Oglala shouted the same words, and we could hear the cry going from camp to camp northward clear to the Santee and Yankton.

Everybody was running now to catch the horses. We were lucky to have ours right there just at that time. My older brother had a sorrel, and he rode away fast toward the Hunkpapa. I had a buckskin. My father came running and said, "Your brother has gone to the Hunkpapa without his gun. Catch him and give it to him. Then come right back to me." He had my six-shooter too – the one my aunt gave me. I took the guns, jumped on my pony, and caught my brother. I could see a big dust rising just beyond the Hunkpapa camp and all the Hunkpapa were running around and yelling, and many were running wet from the river.

Then out of the dust came the soldiers on their big horses. They looked big and strong and tall and they were all shooting. My brother took his gun and yelled for me to go back. There was brushy timber just on the other side of the Hunkpapa and some warriors were gathering there. He made for that place, and I followed him. By now, women and children were running in a crowd downstream. I looked back and saw them all running and scattering up a hillside down yonder.

When we got into the timber, a good many Hunkpapa were there already, and the soldiers were shooting above us so that leaves were falling from the trees where the bullets struck. By now, I could not see what was happening in the village below. It was all dust and cries and thunder; for the women and children were running there, and the warriors were coming on their ponies.

Among us there in the brush and out in the Hunkpapa camp, a cry went up, "Take courage! Don't be a woman! The helpless are out of breath!" I think this was when Gall stopped the Hunkpapa, who had been running away, and turned them back.

I stayed there in the woods a little while and thought of my vision. It made me feel stronger and it seemed that my people were all thunder beings and that the soldiers would be rubbed out.

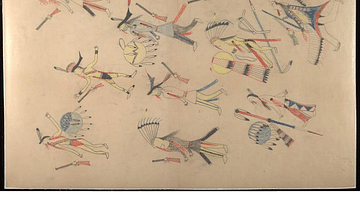

Then another great cry went up out of the dust: "Crazy Horse is coming! Crazy Horse is coming!" Off toward the west and north they were yelling, "Hoka Hey!" like a big wind roaring, and making the tremolo and you could hear eagle bone whistles screaming. The valley went darker with dust and smoke and there were only shadows and a big noise of many cries and hoofs and guns.

On the left of where I was, I could hear the shod hoofs of the soldiers' horses going back into the brush and there was shooting everywhere. Then the hoofs came out of the brush, and I came out and was in among men and horses weaving in and out and going up-stream and everybody was yelling, "Hurry! Hurry!" The soldiers were running upstream, and we were all mixed there in the twilight and the great noise.

I did not see much, but once I saw a Lakota charge at a soldier who stayed behind and fought and was a very brave man. The Lakota took the soldier's horse by the bridle, but the soldier killed him with a six-shooter. I was small and could not crowd in to where the soldiers were, so I did not kill anybody. There were so many ahead of me and it was all dark and mixed up.

Soon, the soldiers were all crowded into the river, and many Lakota too, and I was in the water a while. Men and horses were all mixed up and fighting in the water and it was like hail falling in the river. Then we were out of the river and people were stripping the dead soldiers and putting the clothes on themselves. There was a soldier on the ground, and he was still kicking. A Lakota rode up and said to me, "Boy, get off and scalp him!" I got off [my pony] and started to do it. He had short hair and my knife was not very sharp. He ground his teeth. Then I shot him in the forehead and got his scalp.

Many of our warriors were following the soldiers up a hill on the other side of the river. Everybody else was turning back down stream, and on a hill away down yonder, above the Santee camp, there was a big dust, and our warriors whirling around in and out of it just like swallows, and many guns were going off.

I thought I would show my mother my scalp and so I rode over toward the hill where there was a crowd of women and children. On the way down there, I saw a very pretty young woman among a band of warriors about to go up to the battle on the hill and she was singing like this:

"Brothers, now your friends have come! Be brave! Be Brave! Would you see me taken captive?"

When I rode through the Oglala camp, I saw Rattling Hawk sitting up in his teepee with a gun in his hands and he was all alone there, singing a song of regret that went like this:

"Brothers, what are you doing that I cannot do?"

When I got to the women on the hill, they were all singing and making the tremolo to cheer the men fighting across the river in the dust on the hill. My mother gave a big tremolo just for me when she saw my first scalp.

I stayed there a while with my mother and watched the big dust whirling on the hill across the river, and the horses were coming out of it with empty saddles.