The Wonderful Sack is a legend of the Cheyenne nation and one of the Wihio tales, featuring the trickster figure Wihio, similar to the Lakota Sioux character Iktomi (also known as Unktomi) of the famous Iktomi tales. Although the date of composition is unknown, it is the last of the narrative cycle of Wihio tales.

Wihio shares similarities with many other Native American trickster figures such as Coyote of the Navajo, Nanabozho (Manabozho) of the Ojibwe, and, as noted, Iktomi of the Sioux. The trickster might appear as a villain, a hero, a sage, a clown, or a buffoon but always brings some form of transformation, either for himself, an individual, or the community. The trickster also serves to teach an important cultural value or encourage a certain form of acceptable behavior or, as in The Wonderful Sack, to serve many of these purposes while also providing an audience with an origin tale on where the buffalo came from.

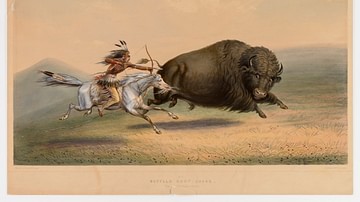

There are many Cheyenne legends of the buffalo explaining where they came from and crediting their creation to various entities. In the Origin of the Buffalo, they are a gift given to the people by the kind grandmother figure, a kind of avatar of the divine, while in How the Buffalo Hunt Began, the origin of hunting the animal is explained. These legends, as well as others such as The Wonderful Sack, highlight the importance of the buffalo (American bison) to the Cheyenne and the other Plains Indians.

The Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Blackfoot, Kiowa, Mandan, Pawnee, Sioux, and many other nations all relied on the buffalo as an essential resource. This was clearly understood by the US government which encouraged the extermination of the buffalo in the West, as a means of subduing the Plains Indians, between c. 1840 and 1890. The Wonderful Sack – and other stories like it – are still told today by Cheyenne as a reminder of their cultural heritage and traditions; as well as a potent remembrance of how they survived the genocidal policies of the US government and still remain an intact nation today.

The Buffalo & Plains Indians

The importance of the buffalo to the Plains Indians is central to many of their legends, and, for the Cheyenne, includes their Cheyenne Creation Story in which the buffalo is instrumental in providing the people with fire to keep them warm at night, in the winter, and for cooking their food. In the Cheyenne legend Falling Star, the hero ensures the survival of his people by subduing the white crow that warned buffalo of the people's approach during a hunt and so saved them from starvation. The importance of the buffalo to the survival of the people of the Great Plains is noted by scholar Adele Nozedar who writes:

The buffalo provided everything that the Native American needed for survival, and the list of uses to which the animal was put is impressive. The hides provided bedding, clothing, shoes, and the "walls" of tipis. The meat was good, nutritious food. The bones and teeth were used to make tools and also sacred implements. The hooves of the animal could be rendered into glue. Horns made cups, ladles, and spoons. Even the tail of the buffalo made a fly whip. The bones could be used to scrape the skin to soften it and was also fashioned into needles and other tools. Some tribes used the bone to make bows. The buffalo provided leather and sinewy "string" for those bows. Even the fibrous dung was used to make fires. The rawhide, heated by fire, thickened; this material was so tough that arrows, and sometimes even bullets, couldn't penetrate it, so it made an effective shield. This rawhide was used to make all manner of objects: moccasin soles, waterproof containers, stirrups, saddles, rattles, and drums for ceremonial purposes, and rope. (62)

Because the buffalo was so important to the people, various tales developed explaining their origin and The Wonderful Sack is only one of many.

Summary & Commentary

In The Wonderful Sack, the trickster Wihio locates a Man-of-Plenty – a figure who appears in many myths around the world, someone who has what everyone else wants and seems to have come to his fortune easily or, at least, mysteriously – according to the understanding of those around him –through the will (in this case) of the Cheyenne Creator God Maheo (Ma'heo'o) the Wise One Above. When Wihio asks for food, it is given, and when he asks for a place to sleep, it is provided. But Wihio wants more – he needs to know what is in the mysterious sack hanging at the back of the lodge and, as one learns later in the story, he also wants everything belonging to the Man-of-Plenty.

In the course of the tale, Wihio gets exactly what he desires. He is able to take over the man's lodge and also gets the mysterious sack, but, lacking the kind of wisdom necessary to manage the object, he eventually releases all the buffalo it holds, freeing them to roam the world and so provide the Cheyenne – and others – with this necessary resource for their survival. The escape of the buffalo also kills Wihio and his family, ending the kinds of antics the trickster had become famous for, even though this archetype would be continued in other forms. The trickster figure is never "evil" and is actually necessary in bringing about change which, otherwise, might not have happened.

Although Wihio's motivation is selfish, his desires bring about a greater good for all. Without the buffalo, the Cheyenne could not have survived – as understood by the US government in the 19th century when they encouraged the wholesale slaughter of the buffalo to deprive the Plains Indians of their most vital resource and so starve them into submission – and so Wihio's theft and opening of the sack actually turns out to be a blessing for the people.

This is a common motif in trickster tales of the Native peoples of North America where the central character engages in some sort of behavior antithetical to the people's values and, at the conclusion of the tale, brings about some good that the people value. In the Sioux story White Plume, for example, the trickster figure Unktomi deceives the hero White Plume, steals his identity, and assumes his position among his fiancé's band, but, by doing so, he highlights the hero's virtue and also, unwittingly, brings White Plume to his future bride and family.

In this same way, The Wonderful Sack shows how even the most selfish desires can be turned to good under the direction of the divine force of an entity like Maheo, who, no matter how people might interpret the circumstances of their lives, is always in control of the final outcome. The piece is known as The Wonderful Sack, not because of Wihio's selfish intentions, but because of how Maheo was able to turn those baser motivations to serve the greater good for all while also punishing the transgressor.

Text

The following tale is taken from By Cheyenne Campfires by anthropologist and historian George Bird Grinnell (l. 1849-1938), first published in 1926. The original date of composition is unknown, as this story, like almost all Native American tales, was passed down through oral transmission from generation to generation until it was written down.

A long time ago, a man was living in a lodge by himself. He had no wife nor family, but about his lodge much meat was hanging on the branches and the drying scaffolds, and he had many hides and robes.

One day Wihio came that way, and entered the lodge and spoke to the man, saying: "I am glad that I have found you, my brother. I have been looking for you for a long time and have asked everyone where you were. At last, I got sure news about you and learned where your lodge was; so I came straight to you."

After Wihio had said this, the man began to cook food for him and, while he was cooking, Wihio was sitting there looking about the lodge. Tied up to a lodge pole at the back of the lodge was a great sack. Wihio could not think what might be in this sack and kept wondering what it contained. The longer he looked at it, the more curious he grew.

After he had eaten, Wihio said to the man, "My brother, may I sleep here tonight with you?" The man said, "Yes, yes, stay if you wish."

When night came, they made up the beds to sleep. The man had been watching Wihio, and had seen him looking at the sack, and thought that Wihio wished to take it; so he took a cupful of water and put it on the ground at the back side of the fire, in front of the sack.

Soon, they went to bed and the man fell asleep; but Wihio did not sleep; he lay there watching and listening.

When the man was sleeping, Wihio arose, and reached up and untied the sack from the lodge pole and put it on his back and started out of the lodge, carrying it.

Before he had gone far, he suddenly came to the shores of a big lake, and started to go around it, running fast so that the man should not overtake him. He ran until nearly morning along the shores of this lake, which seemed to have no end. By this time, he was very tired and sleepy; so he lay down to rest a little, the sack being still on his back so that he could start again just as soon as he awoke.

In the morning, when the man awoke, he saw Wihio laying there with his head on the sack and said to him, "My brother, what are you doing with my sack?"

Wihio awoke and was very much astonished to find himself still in the lodge. He did not know how to answer the man but, at last, he said, "My brother, you have treated me so nicely that I was going to offer to carry your sack for you when you moved."

The man took the sack and tied it to the lodge pole, where it belonged.

After they had eaten, they sat there talking and Wihio said to the man, "My brother, what are you afraid of?" The man replied, "My brother, I am afraid of nothing except a goose."

Wihio said, "I also am afraid of that. A goose is a very dangerous bird." After a little while, Wihio said to the man, "My brother, I am going," and he went out.

When night came, Wihio came back to the camp in the shape of a goose and went behind the lodge and called loudly. The man was frightened and took his sack on his back and rushed out of the lodge and ran away; and Wihio was glad and went back to where he had left his wife and family. When he got to them, he said: "My children, I am glad; now I have got what I have long wished for. I have driven from his lodge a person who has a good home and plenty of food. We will go there and live."

After they reached the lodge, Wihio told his wife about the sack, saying to her, "I want to find out what is in that sack, and I shall follow that man until I do so."

When they had eaten, Wihio set out to follow the tracks of the man, to see where he had gone. He followed him for a long time, but at last he found him and, again, called out like a goose and frightened the man. But when the man ran away, he carried the sack with him. Twice more, Wihio frightened him and, each time, when the man ran away he took the sack; but the fourth time he left it behind him and Wihio took it.

But, when the man dropped the sack, he called out, saying, "I can open that sack only four times!" Now Wihio put the sack on his back and went back to the lodge and said to his wife, "Well, I have got the thing I wished for."

After he had reached the lodge, Wihio untied the sack and opened the mouth, for he wished to see what was in it. As soon as he opened the mouth, a buffalo ran out, and the heads of other cows were seen crowding toward the mouth of the sack. Then Wihio quickly tied it up again.

"Aha," he said, "that is the way I shall do." He killed the buffalo and they had plenty of food. When all the meat was gone, he opened the sack again and another cow ran out and he tied up the sack and killed the cow.

When this mean was gone, he let out another buffalo, and then again, but he had forgotten to keep count of the buffalo he had killed and, when he had opened the sack the fourth time, he said, "That is three times."

A fifth time he opened the sack and, the moment it was opened, many buffalo rushed out and he could not close the sack. They came out in such numbers that they trampled on and killed him and all his family. Not one was left alive.

The buffalo started north and south and west and east and spread all over the world. This is where the buffalo came from; and this is the last of Wihio.