Scribes in ancient Mesopotamia were highly educated individuals trained in writing and reading on diverse subjects. Initially, their purpose was to record financial transactions through trade, but in time, they were integral to every aspect of daily life, from the palace and temple to the modest village or farm. Eventually, they created what is now known as history.

Writing was invented in Sumer, Mesopotamia, circa 3600/3500 BCE, in the form of cuneiform script and refined circa 3200 BCE in the Sumerian city of Uruk. To become a scribe, one had to learn to fashion one's own writing tablet, master the 600 characters of cuneiform, and also become educated in various fields of knowledge, including agriculture, botany, business and finance, construction, mathematics, politics, religion, and many others.

Scribes were almost always the sons of the upper class and nobility, but by the Akkadian period (circa 2350/2334 to 2154 BCE), there is evidence of female scribes, the most famous being Enheduanna (circa 2300 BCE), daughter of Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, reign 2334-2279 BCE). After the Akkadian period, cuneiform script was used primarily to write in Akkadian, but a scribe still needed to know Sumerian, which, though it became a dead language, still informed Akkadian in the same way Latin or Sanskrit does in modern-day languages.

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the other civilizations of Mesopotamia – including the Assyrians, Babylonians, Hittites, Kassites, and others – used cuneiform script to write their own languages, but the scribe still needed to know Sumerian and Akkadian and continued to copy documents from the past. Through this practice, the scribes of ancient Mesopotamia created history by preserving the past in written form.

Writing & Schools

Writing was invented by the Sumerians in response to long-distance trade. As cities developed during the Uruk period (circa 4000-3100 BCE) and trade routes expanded further from centers of production, merchants needed to be able to communicate with their markets clearly. Prior to circa 3500 BCE, this was accomplished by bullae, clay balls in which tokens were baked that stood for a given type of product and the amount (such as five light-colored tokens representing five sheep, three darker tokens signifying sacks of grain), which were marked by a stamp seal identifying the seller.

The stamp seal led to the development of the more intricate cylinder seal by circa 7600 BCE, which came to be used as a form of personal identification. The amount of information that could be relayed by the bullae, stamp seal, and cylinder seal, however, was limited, and so writing developed in the form of pictographs – symbols representing objects – which in time became phonograms – symbols representing sounds – and then logograms – signs representing words.

Once a system of writing was established, it needed to be preserved, and so schools were established, initially in private homes, where a scribe would teach students this new skill. By the time of the Early Dynastic period (circa 2900 to circa 2350/2334 BCE), formal schools had developed and were operating throughout Sumer.

Writing was at first entirely focused on administrative and financial subjects relating to trade. As cuneiform script developed, however, its function expanded to include the communication of knowledge in many different areas. A scribe not only needed to know how to precisely write the characters of the script but had to have knowledge of what was being written about, and this gave rise to the Sumerian scribal school, the edubba ("House of Tablets"), whose educational program would continue throughout Mesopotamia's history.

Curriculum

Students, initially all male unless an upper-class family wanted their daughter to pursue a career requiring literacy, attended class from dawn until dusk. The student body was made up of children of nobility, scribes, clergy, and the merchant class. Education was voluntary and expensive – the father of the student paid for tuition and supplies – and so was denied to children of the lower classes. The exception was slaves – both male and female – who were sometimes sent by their masters to acquire literary skills for any number of reasons. Most students were enrolled in a school by around the age of eight and began their education by learning to create a writing tablet and properly use a stylus. Students graduated from school, generally speaking, in their early twenties.

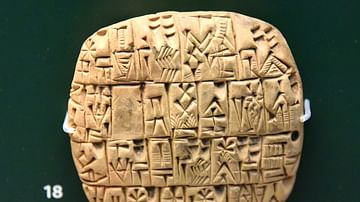

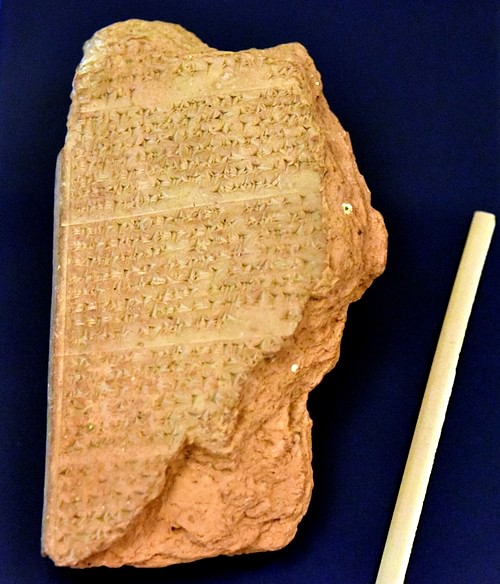

Cuneiform was written by making wedge-shaped impressions in moist clay, but unlike modern scripts and writing materials, the tablet had to be formed by the writer and would then be turned in different directions in one hand while one struck the impressions into it using the stylus (usually a sharpened reed, which the scribe would also make) with the other. Tablets could be the size of one's hand or considerably larger. After learning the basics of technique, students began the process of copying and memorizing the different signs that made up words and sentences.

According to scholar A. Leo Oppenheim, as explained by Assyriologists Megan Lewis and Joshua Bowen of Digital Hammurabi, there were four types of tablets, which represent the four stages of the student's progress:

- Type 1: large, multi-column tablets

- Type 2: 2-column instructor-student tablets

- Type 3: 1-column tablets with c. 25% of a composition

- Type 4: 'lentil-shaped' tablets with basic writing

Tablets excavated at sites in modern-day Iraq and Syria, as well as other evidence, including texts on education, have allowed scholars to reconstruct the four stages of a student's educational program:

- Stage 1: Type 4 Tablet - 'Lentil-shaped' tablets of simple writing exercises designed to teach a student to make proper wedges and signs.

- Stage 2: Type 2 Tablet – The instructor would write on the left side of the tablet, and the student would copy that text on the right, often erasing errors – so the right side of tablets found in the present day is usually thinner than the left due to the loss of clay. The reverse of the tablet held text which had already been completed and memorized, or, in other words, a previous lesson.

- Stage 3: Type 3 Tablet – These tablets hold a quarter or more of a long composition that had been completed and memorized.

- Stage 4: Type 1 Tablet – Complete compositions were created from memory and demonstrate a mastery of cuneiform script.

Once the script had been mastered and the students educated in reading, math, history, and other subjects, they moved on to the Tetrad (groups of four compositions) of greater difficulty, which they would copy repeatedly, memorize, and recite. The next course of study was the Decad (groups of ten compositions) of even greater difficulty. The Tetrad's compositions included works such as the Hymn to Nisaba (Sumerian goddess of writing), which is a straightforward praise song. The Decad included more complex and nuanced works, such as Gilgamesh and Huwawa and Song of the Hoe, which required a firmer grasp of style and interpretation.

Once these were mastered, the student was required to engage with even more complicated texts such as Schooldays, Debate Between Sheep and Grain, and A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe, among many others. After completing this last stage, the student graduated as a scribe. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments on the final goal of the curriculum:

Formal education involved the mastery of literacy (for such tasks as maintaining business records, writing and reading contracts, composing letters, sending military messages, reciting prayers and incantations, and understanding medical texts) as well as the mastery of numeracy (for such jobs as measuring plots of land and their produce, determining taxes, projecting supplies for a military campaign, figuring out the amount of earth needed to construct a siege ramp, estimating the number of bricks required to erect a new palace, or making celestial calculations). Ultimately, specialized vocabulary would have to be mastered in such fields as astronomy, geography, mineralogy, zoology, botany, medicine, engineering, and architecture.

(302-303)

From the Akkadian period onward, students also needed to master Sumerian and Akkadian as well as their own language. Upon graduation, the scribe was formally known in Sumerian as a dub.sar ("tablet writer" literally from dub=tablet and sar=writer) or, in Akkadian, Assyrian, and Babylonian, as a tupshar (also given as tupsharru), which meant the same thing. The headmaster of a Sumerian school was known as the ummia ("expert" or "master professor"), but a variation on this term also seems to have been applied to a highly educated scribe at court or the temple. In the later Hittite period, the title became gal dubsar ("chief of scribes"), and it was one of the most important positions in government, just as it would be in the Assyrian period when the position of tupsar ekalli ("palace scribe") was second only to the king.

The Life of the Scribe

Throughout Mesopotamia's long history, beginning in the Early Dynastic period all the way through the Sassanian Empire (224-651), scribes were referenced in terms of the highest respect. Long before the time of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (7th to 6th century BCE), during which scribes were frequently mentioned with great reverence as servants of the god of writing Nabu (who had replaced the goddess Nisaba), scribes were recognized as an elite social class. To attain this position, however, one needed to be wholly committed to one's education and be willing to endure daily corporal punishment at the hands of one's teachers.

Schooldays and A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe, both well-known Sumerian poems, detail the challenges a would-be scribe faced in the course of their education. Both works are understood as satire but, like any satire, are framed within the reality of the situation they are making fun of. In Schooldays, the student relates how he is beaten daily by his teachers for infractions ranging from tardiness to poor penmanship (having a "bad hand") to standing without permission, talking without permission, poor posture, unauthorized absence, and leaving school early without permission. The satirical aspect of the work is how he resolves his problem: he gets his father to bribe his teacher with a lavish dinner and fine gifts to give him better grades and fewer beatings.

In A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe, the teacher relates how a student must do exactly as instructed by his mentor, not resting even at night in mastering the craft, and must learn and obey every rule without question. The rules of the edubba, no matter how harsh they may have seemed, were designed to encourage discipline and focus in the students, and the teacher emphasizes these aspects.

When the young scribe in the poem, a recent graduate, responds to the teacher, he relates all the tasks he has performed well in his mentor's service, including managing his household affairs, paying his staff, preparing offerings for the temple, overseeing agricultural produce and workers, and ensuring quality control. It is only after the student has made clear how well he has absorbed and practiced his teacher's lessons that he receives his mentor's (supervisor's) blessing as a scribe. In this work, the satire rests on how the student has essentially become the teacher's slave in order to receive an education.

Once graduated, the scribe might work directly for the king, in the bureaucracy of the palace, at the temple complex, in private business, in the military, for construction companies, in trade, as a diplomat, or as a teacher, doctor, dentist, or any other occupation requiring literacy. In small towns and villages, the scribe would write personal letters for people and make sure they had sent the proper amount of grain or other produce as taxes. They would also assist in the design and calculations for the construction of buildings, irrigation ditches, or in land disputes between farmers over boundaries. Scribes were usually paid in grain, beer, or whatever a person could offer of value.

Famous Scribes

Since most of the population was illiterate, the skills of the scribe were in high demand. Scribes are sometimes described as "those who never go hungry", and many were among the most powerful people in their city. The scribe Azi (2500 BCE) is known as a popular scribe in the city of Ebla (in modern-day Syria) and was known as dub.zu.zu ("One Who Knows Tablets"), suggesting he was a "chief of scribes" but, perhaps, even more highly educated and skilled.

Enheduanna was the high priestess of the temple complex of Ur, the most powerful religious position in the city. She would have not only kept the temple's records but is also famous for her original poetry, prayers, and hymns dedicated to the goddess Inanna (later known as Ishtar). Enheduanna, in fact, is the first author in the world known by name, and her works would influence those of later writers, including the Hebrew scribes who wrote the Psalms of the Bible.

The scribe Arad-Nanna of the Ur III period (circa 2112 to circa 2004 BCE) was also a powerful figure in the city. Although he technically served the kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur, his cylinder seal shows him approaching the royal figure on the throne as an equal, while a goddess figure, standing behind him, is depicted in a pose of reverence and respect. Shulgi of Ur (reign 2094 to circa 2046 BCE) was also known as a scribe who wrote poetry and encouraged literacy and the establishment of schools throughout his kingdom.

Another influential scribe was the Babylonian Shin-Leqi-Unninni (wrote circa 1300-1000 BCE), who drew on earlier Sumerian poems of the life of the hero Gilgamesh to create the first epic tale in world literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh. His work would also go on to influence some of the most famous poems in the world, including, according to some scholars, Homer's Iliad.

Most scribes created their works anonymously, however, and their names are unknown. By circa 2600 BCE, however, scribes would sometimes sign their name to a work, or their name would be recorded by another for a certain accomplishment. A list of scribes' names found in the ruins of Nineveh relates how they were responsible for copying and editing the works gathered by the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (who was also trained as a scribe) for his library. These scribes would have been comparable to the sepiru ("scribe-interpreter") of the Neo-Babylonian period, who worked for the state, temple, or for wealthy private citizens, interpreting, copying, and creating books.

Conclusion

In time, and relatively early in Sumer, scribes became authors – creators of original works – of hymns to various deities and poems about them, including those on Gilgamesh and Inanna. Scribes were responsible for the inscriptions of kings and the creation of naru – an engraved stele recounting the events of a monarch's reign – and so became the keepers of history. At some point around the 2nd millennium BCE, the creation of a naru blended with creative scribal energies to produce a genre of work known as Mesopotamian naru literature, which featured a king in a fictional setting.

Some of the most famous works of this genre are also among the best-known of all Mesopotamian literature: The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, The Curse of Agade, The Legend of Cutha, and The Epic of Gilgamesh. In all of these and others, some great historical figure faces a challenge they did not or may not have in reality, and the scribe's purpose in the piece was to relate some central moral, religious, or cultural value. In this way, Mesopotamian scribes created the first historical fiction, but before they could do that, they had to create history.

Before the invention of writing, whatever events transpired were preserved by oral tradition, which might alter details with every new telling. After writing developed, it was possible to set down events in a form that could be read over and over in the same way. The events of the past were now accessible to people in the present, encouraging the development of culture, standard language practices, and social/religious traditions. The original stories crafted by the scribes impressed the culture's values on those who heard them read, leading to the development of personal and communal identity and, finally, the story of the people, which, in time, came to be known as history – a concept unknown prior to the work of the Mesopotamian scribe.