The evacuation of children from British cities during the Second World War (1939-45) was the largest population movement the country has ever experienced. Some 6 million women and children voluntarily evacuated from large cities to live with relations, family friends, and foster parents in towns and villages in rural areas much less likely to be bombed by the enemy. Many children were sent even further afield to such countries as Canada, the United States, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

Operation Pied Piper

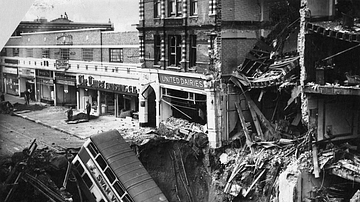

The British government greatly feared the potential loss of life from an air war, and so even before WWII began, a scheme was devised to evacuate children and some women from the cities most likely to be bombed. Operation Pied Piper, as the voluntary evacuation scheme was called, ensured that 4 million women and children were evacuated to safer locations while another 2 million were evacuated outside the government scheme. As it turned out, the government had been correct about the dangers of aerial bombing. Through the course of the war, Germany's bombing of Britain resulted in 60,000 civilian deaths and another 140,000 injured. Of these figures, 15,000 children were amongst the killed and injured. Evacuation of children from cities vulnerable to aerial bombing was carried out by other states during the war, notably in Germany, the Soviet Union, and Japan. Britain's national evacuation scheme, though, was carried out on a much larger scale than anywhere else. The scheme saved lives, but there was a cost as families were separated, and the experience of having to adapt to an entirely different way of life proved traumatic for many children.

The evacuation of children was first seen in Britain before the war had started. Between November 1938 and September 1939, 10,000 children were evacuated from Germany and Austria by parents concerned for the future under Nazi rule; 9,000 of these children had Jewish parents. The children were sent to Britain in the hope, still entertained at this point, that that country might not become directly involved in a war that looked inevitable in continental Europe. As it turned out, British civilian populations would also be subject to attack, this time from the air.

The Phoney War

A few days before the war started, on 1 September 1939, the UK government began to evacuate children (aged 5 to 14, the school leaving age at the time) and some women from certain cities. Priority was given to younger children and those with physical disabilities. In just a few days, 827,000 children, the younger ones with their mothers (524,000 of them), headed off to safe places in trains laid on by the government.

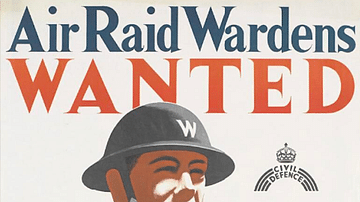

Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939 after the latter's invasion of Poland. In the following months, while German forces overran parts of Western and Eastern Europe, Britain remained relatively unaffected. This period, between September 1939 and the spring of 1940, was called the Phoney War since British civilians had little tangible evidence there was a war going on. The period brought a sense of false security for many, and this affected the government's efforts to evacuate children. As the historian J. Hale points out: "By January 1940 about half of all children and nine out of ten mothers had returned to their old homes" (27). Some historians put the figure of returnees as high as 80%. The government encouraged parents to evacuate their children through posters and advertisements in newspapers, and by sending officials to people's doors to plead the case for evacuation. Other inducements included subsidised train tickets for parents to visit evacuated children at weekends and reminding them that "useless mouths to feed" in the big cities would hinder the war effort. Although politicians discussed it, the evacuation scheme was never made compulsory. The sentiment really only changed when the German Luftwaffe (Air Force) started systematically bombing London and other cities in the last quarter of 1940 and through 1941. Evacuation then became a much more attractive proposition.

Sending off children to new homes, even if a temporary measure, was a difficult decision to make for many, as explained by Lucy Faithfull, a child evacuee organiser in London:

When the evacuation scheme was first announced by the government and it was explained to the people what the evacuation scheme was, this posed the parents the most terrible and cruel dilemma. And particularly for women – the men knew they must stay in London – the women had to decide whether to go out with their children under five or whether to stay in London, whether to keep their schoolchildren with them or whether to allow them to go out. No one should think this was an easy decision – why not keep your children with you, which is the natural thing to do? But against this was the terrible thought that there was going to be gas, that there was going to be terrible bombing and death, and the children would be maimed. And by and large, with of course notable exceptions, parents did decide to send their children out and I always feel that probably they did this knowing the teachers, and knowing that their children would be in the charge of the teachers whom they knew and whom they respected. (Holmes, 390)

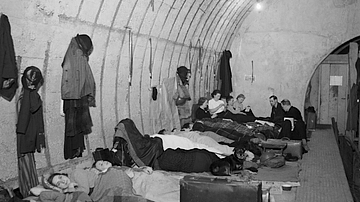

The voluntary evacuation scheme did attract many parents, but, in London, for example, less than half of parents decided, in the end, to evacuate their children. This still meant that one million children were evacuated from the capital alone in order to avoid the London Blitz, a sustained bombing campaign, which lasted from September 1940 to May 1941. In all, some 6 million children and mothers left British cities for the safety of rural Britain. An army of volunteers, particularly teachers, railway staff, and members of the Women's Voluntary Service (WVS), collected the children, looked after them as they travelled, and handed them over to their volunteer foster parents. There were some flaws in the system, notably that foster parents and children were rarely matched in terms of best suitability. Another flaw was that those children who were not evacuated were very often left without a school to go to since the teachers were no longer available and, at least in London, two-thirds of schools were requisitioned for other uses like air raid shelters or post-raid aid centres. The consequence of children having nothing to do led to a dramatic rise in juvenile delinquency in cities.

Trip of a Lifetime

Most evacuated children were packed off in trains to reach their new homes, travelling in groups organised according to the schools they had attended. Each child travelled with a bag or suitcase of essentials. Parents had been advised by the authorities what they should pack for their children, items like a coat, spare underclothes, socks, handkerchiefs, night clothes, a pair of plimsolls, a towel, a comb, a bar of soap, and a toothbrush. Children also carried a gas mask and wore a paper identification tag.

Those who went abroad travelled by ship. The American Committee for the Evacuation of Children dealt with 35,000 requests to evacuate children to the USA, although only around 2,000 British children ended up in US families for the duration of the war. Travelling on liners was common but hazardous. In just one example, the liner SS City of Benares was hit by a German U-boat torpedo in September 1940 while on its way to Canada. Amongst the dead were 77 children evacuees. The disaster prompted the cancellation of the overseas evacuation programme.

Naturally, parting ways was a sad experience for both parents and children, as Lucy Faithfull explains:

When the train drew out a kind of stillness came in the train when the children realised they were leaving parents behind, and they weren't parents who were waving gaily to them but parents with tears streaming from their eyes thinking they'd never see their children again.

(Holmes, 390)

Children were housed by volunteer foster parents, who came to meet the trains of evacuees or gathered in a local hall to claim their evacuees. Lucy Faithfull describes this part of the process:

[The children] would be herded into some hall, then the foster parents – the people who were going to have children billeted on them – would come to the hall and some of them were wonderful, some of them would just take children for the sake of the child. Sadly, others would choose children and then there would be the terrible situation that at the end one or two unattractive children would be left., and I can remember one case when nobody would have this child and there was this terrible sense of loss on the child's part.

(Holmes, 390-1)

Some hosts volunteered to take a single child, others siblings, and still others a whole batch, like Oliver Lyttelton, the President of the Board of Trade, who took in 11 evacuees. A parallel, private evacuation went on between family and friends with many parents taking advantage of connections in rural Britain to send their children to the home of a relative or family friend. A third aspect of evacuation was those stately homes which were converted into children's homes for the war where a large number of evacuees could be looked after in one place. Those who took in evacuees were entitled to an allowance from the government to pay for the extra food and clothing required.

Making a New Home

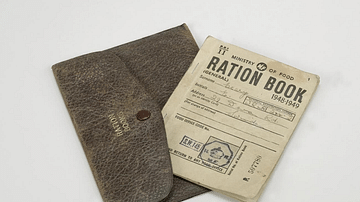

The children's new homes were often very different from what they were used to. Some children revelled in the new experience, enjoying for the first time the countryside or the seaside, for example. New friends were made, new food was enjoyed (or detested), and many children saw things for the first time in their lives, such as farm animals. Perhaps inevitably, many children suffered from being homesick, some long-term and with consequent psychological issues. There were clashes of habits as to what had been normal at home and what was now expected of children. Many hosts were surprised at the lack of hygiene of some evacuees from inner cities. On the other hand, many children were pleasantly surprised by a better and more varied diet available to them in rural Britain, particularly after the introduction of rationing in wartime Britain in the first months of 1940. Some children found their new homes better equipped in terms of sanitation and general comfort; others found the opposite, especially those billeted to farms where running water and electricity were both absent. Some children were abused (as legal cases demonstrate), and some were pushed into work, especially on farms. Children went to local schools, but here, too, there were problems of integration; having one's accent laughed at was one of the milder aspects of being an outsider in previously closed communities. All in all, then, evacuation was a real mixed bag of emotions and experiences, and, one way or another, it affected evacuees long into their adult lives.

Children could keep in touch with their parents via letter and older ones must have anxiously kept up-to-date on the bombings in their home cities through newspapers and newsreel stories. Returning to the cities for holidays like Christmas was not recommended but, unsurprisingly, frequently happened anyway. Despite these lifelines of contact, most children were cast adrift from their old family life as memories of home receded into the depths of a half-forgotten past.

The Return Home

Fortunately for everyone, evacuation was a temporary measure. Indeed, many children and mothers returned to their homes (if they were still standing) in 1942 after the aerial bombing died down, but towards the end of the war, when German V-rockets were being sent over the Channel, the evacuations started all over again. When the war was finally over in 1945, many children were sad to leave their foster parents as they endured another wrench in their lives and returned to the family homes many of them could hardly remember. Other children were, of course, all too glad to get home, as John Geer remembers: "London was, for me, like a return from exile. My pet cat met me at the gate, the neighbours welcomed me and the sun shone." (Ziegler, 60)

The government was interested in observing the effects of evacuation on the children involved and conducted several studies comparing groups of children who stayed at home in the cities with those who were evacuated to the countryside. It was found that the children who had remained in the cities "were taller, were heavier and were emotionally more balanced and happier children than those who had been in billets in the country" (Holmes, 403).

The evacuation scheme, like so many aspects of the war on the home front, had mixed up the various social classes, exposed the differences in living standards between town and country, and resulted in everyone learning to see life a little differently, as here explained by Lucy Faithfull:

During the whole of the evacuation period I think that in the field of child care and in the field of family life we learned more than we perhaps would ever have learned otherwise. I think that the great mix-up of different types of people in different areas, town and country to the forefront, underlined a tremendous need in the country overall, and I think therefore that the evacuation as the impetus to social legislation following the war.

(Holmes, 404)