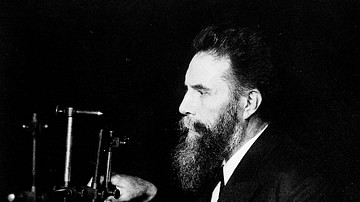

The discovery of X-rays – a form of invisible radiation that can pass through objects, including human tissue – revolutionised science and medicine in the late 19th century. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845-1923), a German scientist, discovered X-rays or Röntgen rays in November 1895. He was awarded the first Nobel Prize for Physics for this discovery in 1901.

The thrill of the discovery became caught up in the late Victorian obsession with ghosts and photography. X-rays could 'photograph' the invisible, penetrating flesh, exposing bones and the human skeleton. 'Bone portraits' became popular, and photographers opened studios for a public fascinated by otherworldly images of skeletons.

One of the first medical uses of X-rays occurred in 1896 when John Francis Hall-Edwards (1858-1926), a British doctor, located a needle embedded in a colleague's hand. X-ray technology soon moved from being seen as a new form of photography to a modern diagnostic tool used by hospitals and medical practitioners.

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was a meticulous scientist, but the discovery of X-rays may have been an unintentional result of his work with cathode rays in his Würzburg laboratory in Bavaria, Germany.

Early Years

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was born in Lennep, Prussia (Remscheid-Lennep, Germany) on 27 March 1845, to a German textile merchant father and a Dutch mother. He was an only child and spent his early years in Apeldoorn in the Netherlands. His father, Friedrich Conrad Röntgen (1801-1884), managed a cloth manufacturing business in Apeldoorn. The family had also moved due to political unrest in Prussia.

Röntgen attended the Utrecht Technical School from 1861 to 1863 but was expelled when a fellow student drew a caricature of a teacher. Röntgen was implicated but refused to name the student responsible. Despite excellent marks, he did not graduate with a technical diploma and could not obtain a degree in the Netherlands. He was accepted by the Mechanical Technical Division of the Federal Polytechnic School in Switzerland in 1865, where he gained a diploma in mechanical engineering and, in 1869, a PhD in physics with his thesis Studies on Gases.

The German experimental physicist August Kundt (1839-1894) was Röntgen's supervisor. In 1866, Kundt designed the Kundt Tube, a glass apparatus that measured the speed of sound in gases. Kundt significantly influenced Röntgen and his research career.

Röntgen followed Kundt to the University of Würzburg in 1870, where he worked as an unpaid assistant during a time of rapid advancements in experimental physics. Scottish mathematician James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) was researching electromagnetic radiation and established the connection between light and electromagnetic radiation. Maxwell also took the first colour photograph in 1861, based on his three-colour theory that the human eye sees colour through a combination of blue, red, and green light. Massachusetts-born Samuel Morse (1791-1872) developed the electric telegraph, which transmitted messages over long distances, and Morse code to encode messages, while Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) invented the telephone.

Of particular interest to Röntgen was the work of German physicist Heinrich Hertz (1857-1894) and British chemist William Crookes (1832-1919). Both scientists studied cathode rays – invisible streams of electrons whose behaviour can be observed when an electrical current is passed between the two electrodes (cathode and anode) in a glass vacuum tube. It is called a cathode ray because the electrons are emitted from the cathode (or negative electrode) when an electrical current heats it, and the electron stream glows. Johann Wilhelm Hittorf (1824-1914) was the first to detect cathode rays glowing green in the glass wall of a vacuum tube in 1869 but did not realise that X-rays had been produced during his experiments.

Röntgen became fascinated with the fluorescence caused by cathode rays hitting certain materials, such as salts like barium platinocyanide, which glow a greenish-yellow colour when exposed to cathode rays. It was this fascination that led to the discovery of X-rays.

Steps To Discovery

By 1895, Röntgen was a professor of physics at the University of Würzburg and, at 50 years old, at the height of his career. During the 18th and 19th centuries, many scientists experimented with electricity and vacuum tubes and came close to discovering X-rays. Their experiments were crucial steps that led to Röntgen's discovery.

In 1705, British scientist Francis Hauksbee (1660-1713) researched static electricity generation. He removed most of the air from a glass globe and produced a glow by spinning and rubbing it with his hands. Hauksbee saw a bluish-purple light in the darkened room, enough to see the outline of his hand when he placed it on the globe, but he had no theoretical explanation for the light. Hauksbee had inadvertently invented the neon light and demonstrated that electrical phenomena could generate light.

In February 1890, American physicist Arthur Willis Goodspeed (1860-1943) took the first X-ray image. He experimented with electrical discharges in a Crookes tube (an early vacuum tube) at the University of Pennsylvania. Unexposed photographic plates and coins nearby were exposed to X-ray radiation from the Crookes tube. Goodspeed complained to the photographic plate supplier because a shadowy shape appeared on one of the developed images. Goodspeed did not realise he had taken an X-ray photograph of the coins, and he filed it away. Only when Röntgen announced the discovery of X-rays in his paper On a New Kind of Rays (published on December 28, 1895) did Goodspeed understand he had observed X-rays almost six years earlier. In February 1896, during a lecture at the American Philosophical Society, Goodspeed stated:

Now, gentlemen, we wish it clearly understood that we claim no credit whatever for what seems to have been a most interesting accident, yet the evidence seems quite convincing that the first Röntgen shadow picture was really produced almost exactly six years ago to-night, in the physical lecture room of the University of Pennsylvania.

(Goodspeed, 24)

Heinrich Hertz's student and assistant, Hungarian-born Philipp Lenard (1862-1947), narrowly missed the discovery of X-rays and later resented Röntgen being credited. He claimed his experiments with cathode rays led directly to Röntgen's discovery and that he was the 'mother of the X-rays' because he had invented the vacuum tube that Röntgen used in his many experiments.

Hertz had shown that cathode rays could penetrate thin metal foil, and, in 1892, Lenard designed an improved glass tube with an aluminium window at the end — called the Lenard Window — which would allow cathode rays to exit the tube so they could be studied outside the tube itself. He coated a plate with the chemical compound ketone and saw that the cathode rays darkened parts of the plate at a distance of 8 centimetres (3.1 in) and that other areas glowed. This meant cathode rays had enough energy to cause visible light, but Lenard failed to understand that a different type of ray had been produced.

Röntgen heard of Lenard's experiment and wanted to reproduce it. The two exchanged letters, and Röntgen ordered ketone, which was slow to arrive from the manufacturer. Röntgen used barium platinocyanide instead, which was a chemical compound known at the time for its ability to fluoresce in ultraviolet light. The replacement of the chemical compound, combined with Röntgen's rigorous observation and repeated experimentation, likely led to him being credited as the discoverer of the X-ray rather than the many scientists before him who had unwittingly observed invisible radiation.

On Friday evening, November 8, 1895, in his darkened laboratory at the University of Würzburg, Röntgen covered a vacuum tube with black cardboard and fired a high-speed electrical current from the cathode to the anode. Covering the tube blocked any glow that might be emitted. A board coated with barium platinocyanide glowed a faint yellow-green and Röntgen understood that rays from the tube had a luminescent effect.

Röntgen locked himself in his laboratory, even sleeping there. Over several weeks, he took X-ray images, the most famous being "Hand mit Ringen" ("Hand with Rings") taken in December 1895 of his wife's left hand. Anna Bertha Röntgen (1839-1919), whom Röntgen had married in 1872, was the first person to experience an X-ray being taken, and the image showed her wedding ring and the bones of her hand. After looking at the X-ray, Anna Röntgen exclaimed that she had seen death.

Although the common term is X-rays (with X representing an unknown quantity in mathematics), they were mainly referred to as Röntgen rays at the time of discovery. Röntgen demonstrated that X-rays could penetrate glass, paper, metal, and human tissue. British physicist and president of the Royal Society, Lord Kelvin (1824-1907), was sceptical and promptly declared X-rays a hoax, and priority claims also arose. One particularly distressing claim for Röntgen was that of Philipp Lenard, who believed he was the rightful discoverer of the new rays. Lenard had sent Röntgen one of his specially designed glass vacuum tubes and also shared crucial information from his 1892 cathode ray experiments. Without this, Lenard argued, Röntgen would not have been able to achieve his historic breakthrough.

Lenard's resentment was further fuelled when Röntgen was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1901, and his bitterness lasted well into the 1930s when Lenard became caught up in German nationalism and anti-Semitism. Despite being awarded the Nobel Prize in 1905 for his work on cathode rays, Lenard continuously sought to discredit Röntgen's discovery. The Third Reich supported Lenard's claim that high-frequency rays, as he called them, had not been discovered by Röntgen.

Bone Portraits & Harmful Effects

X-rays were first seen as a marvellous new form of photography, capturing the Victorian public's imagination. Because X-rays could see through clothing and produce an outline of the human body, there were concerns over modesty and privacy. In an 1896 issue of Electrical World, a London company advertised lead underwear as a form of protection. Nevertheless, photographic studios and fun fairs took advantage of the X-ray craze of 1896. People lined up to have their skeletal images captured in bone portraits. "Hand mit Ringen" is considered the first bone portrait.

Unwrapped Egyptian mummies were X-rayed. Fraudulent spiritualists exploited the public's limited understanding of the new technology, particularly the confusion over the difference between cathode rays and X-rays. They used special processes to trick people into believing a ghostly-looking skeleton in a photograph was their deceased loved one.

Medical practitioners referred their patients to photographers before the diagnostic value of X-rays was realised. By 1898, though, the public's interest had waned, and X-ray technology had moved into the medical field, with hospitals offering X-ray treatment. American Émil Grubbé (1875-1960) was possibly the world's first oncologist, treating a breast cancer patient for one hour with radiation in 1896.

The damaging effects of exposure to radiation became apparent by the early 1900s, with reported cases of burns and itching skin (known at the time as X-ray dermatitis). Thomas Edison's (1847-1931) assistant, Clarence Dally (1865-1904), suffered from swollen hands and peeling skin after exposure to X-rays over an eight-year period. On hearing of Röntgen's discovery, Edison experimented with X-rays and developed the fluoroscope, a machine that uses X-rays to show internal organs in motion like a film. He ceased his experiments when Dally had both arms amputated due to prolonged radiation exposure. Dally died in 1904 from cancer at the age of 39.

Hall-Edwards also lost his left arm and four fingers from his right hand to prevent the spread of radiation-induced necrosis. Émil Grubbé suffered from radiation-induced cancer, enduring over 90 operations to treat severe burns and complications before his death. Safety legislation was only introduced in England and the United States in 1921, but many X-ray pioneers had already died. Röntgen succumbed to intestinal cancer shortly after, in February 1923.

The medical field now understands certain types of radiation can alter DNA, leading to the rapid multiplication of cancerous cells. Yet, from the 1920s until as recently as the mid-1950s, a coin-operated machine called the Foot-O-Scope was a common fixture in shoe stores. An X-ray image of the bones in the foot and an outline of the shoe helped parents check whether the shoe was a good fit for the child. The machine was called a Pedoscope in England and used fluoroscopy. The shoe salesperson would expose themselves to a burst of radiation from the fluoroscope several times a day. By 1950, 10,000 machines were operating without regulation in the United States. In 1957, Pennsylvania banned the shoe-fitting fluoroscope, becoming the first US state to take action. Fluoroscopy was also used during World War I to X-ray the feet of wounded soldiers without the need to remove their boots.

Röntgen's Later Years

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen did not enjoy the limelight. He did not attend or lecture at the 1901 Nobel Prize award ceremony, nor did he seek to profit from his discovery by taking out a patent. He believed X-ray technology should be freely available and donated his Nobel Prize money (around USD 40,000) to the University of Würzburg. Röntgen was independently well-off, thanks to his father's textile business.

Röntgen moved to the University of Munich in 1900, where he was chair of experimental physics until his retirement in 1920. Anna Bertha Röntgen died in 1919 following a prolonged illness. When hyperinflation hit Germany in 1921, Röntgen lost a significant amount of his wealth. He stipulated in his will that most of his laboratory notebooks and correspondence be destroyed. This raises the question of whether Röntgen was troubled by ongoing rumours concerning the true discoverer of X-rays.

Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) claimed he had been working with X-rays (which he called shadowgraphs) since the early 1890s. A fire at his New York laboratory in March 1895 resulted in Tesla's notes and photographs being lost, so his claims could not be substantiated. Philipp Lenard's bitterness continued to plague Röntgen, so perhaps Röntgen's personal records were destroyed to prevent them from falling into the hands of rivals or being misused.

Whatever the reason for Röntgen's instructions that his scientific papers be destroyed, history records that in 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, working in a darkened lab, discovered a new, unknown type of ray, which revolutionised medical imaging.