Christianity arrived in Japan in 1549 when Jesuits first set foot in Kagoshima. Initial attempts to spread the religion were met with confusion; however, through employing various methods, they began to see success. However, by 1650, Christianity had effectively vanished from open society as the isolationist policy of Japan brought with it suppression and persecution.

Anjirō & Francis Xavier

Arguably, the first Jesuits to come ashore in Japan may have not found the success they did if they had not been accompanied by Japanese-born Anjirō (or Yajiro), who was at once both a help and a hindrance to the mission. Fleeing murder charges, Anjirō stowed away on a Portuguese vessel and was followed by two companions, one of which may have been his brother. Leaving the land he knew for an unknown future, he found himself in the city of Macao, China, a major trading hub of the Portuguese Empire. Anjirō picked up the Portuguese language in less than a year and showed a great interest in Christianity. Seeking further knowledge, he and his companions tracked down the famed Apostle of the Far East, Francis Xavier, who was based out of Portuguese Malacca, Malaysia. Anjirō impressed Xavier with his questions, prompting the Jesuit priest to write:

If all the Japanese are as eager to know as is Anjirō, it seems to me that this race is the most curious of all the peoples that have been discovered

(quoted in Dougill, 13).

After their meeting, Xavier recommended that Anjirō and his companions travel to Portuguese Goa, India, to learn more about the faith, and it was here that they became the first Japanese to convert to Christianity. Xavier later requisitioned a report about the Japanese people from a Portuguese captain, and along with Father Cosme de Torres, Brother Juan Fernandes, an Indian retainer, and the three Japanese converts, set off for Japan in what would be a surreal experience for both the natives of the land and the foreigners.

Apostle of the East

Saint Francis Xavier (1506-1552) was one of the founders of the Society of Jesus, who called themselves Jesuits. Prominent for his missionary efforts in India, Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan, and China, he devoted much of his efforts to evangelising the Japanese, as he believed that the message would spread quickly throughout the land. Having converted, cumulatively throughout his missionary travels, some 30,000 people, Francis Xavier is remembered as one of the greatest champions of the Catholic faith.

Xavier also supported the idea that a missionary should learn from the local culture, study the language, and train native preachers, a rare belief in his day. He would eventually succumb to a fever on Shangchuan, an island off China's coast. He was beatified in 1619 and canonised in 1622. Today, he is venerated on 3 December, his feast day, with his relics being displayed across the world.

The Portuguese, having first reached India in 1498, captured the city of Malacca in 1511. Malacca proved to be an important stop for traders travelling from the Indian Ocean and further east towards China and Japan. Portuguese control over the region secured their place as a powerful trading nation and presented difficulties for rival nations seeking to establish a foothold in the region. Not long after the capture of Malacca, missionaries arrived setting up churches and schools across the wider region and proselytising with varying levels of success.

First Contact & Language Barrier

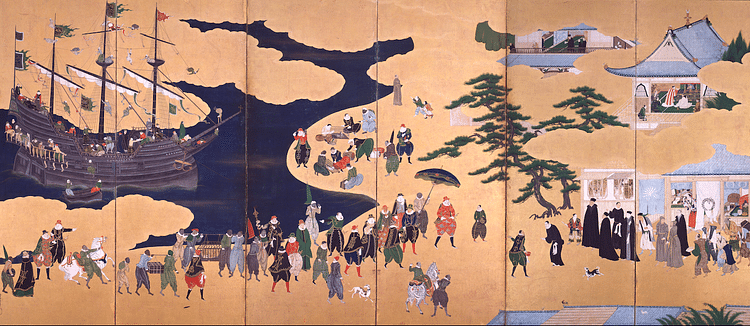

The Japanese referred to foreigners as nanbanjin, or 'southern barbarians' owing to their initial appearance on the southern island of Tanegashima in 1543, when a group of Portuguese merchants travelling aboard a Chinese junk found themselves shipwrecked after a storm. A somewhat derogatory term then, the word has taken on new meaning today, with there even being Nanban Festivals held across Japan – a celebration of history, culture, and connection.

Coincidentally, Xavier's party landed where Anjirō left his homeland – in Kagoshima. The Japanese described the Europeans as having "saucer-like eyes, elongated, claw-like hands, and long teeth" (Clements, 2). The Jesuits' bald, tonsured heads were compared to the shaved top of a kappa, a Japanese water sprite, and their elongated noses were said to look like the beak of a tengu, a demon that resembled a bird and a harbinger of war.

The language barrier proved to be a hurdle that could not simply be crossed by solely employing the assistance of interpreters, a role that Anjirō and his companions temporarily filled. The priests needed to be able to converse in the local language in order to ensure the reliability of the message. Xavier wrote:

Till now we are among them like statues, since they speak and say many things about us, and we ourselves, since we do not understand the language, are mute; and we must now become like little children in learning the language.

(quoted in Taida, 11)

Within 40 days of starting his studies, Xavier began to proselytise in a broken Japanese by explaining the Ten Commandments to a group of locals. While he never learned to read or write Japanese, he phonetically wrote what he heard using Roman letters, which is called Romaji today. Steadily improving his language skills, the priest would carry himself up to the local temples to debate with the monks that resided there, often being met with laughs at his tenuous grasp of Japanese. Not perturbed, he and his fellow Jesuit priests would stay up late into the night studying the intricate dialect.

Although Xavier never became fluent in Japanese, he did petition the church in Europe to send priests who "have talent for learning the language" (Taida, 15). Aside from this, he would later build a school in Yamaguchi to train local interpreters so that they might, at least temporarily, be able to preach in this manner. Xavier praised his Jesuit brethren who studied and were able to freely converse in Japanese, as he knew that this was the ultimate way of spreading their message, even though he and other Jesuits of high authority in Japan (Cosme de Torres, Francisco Cabral, and Alessandro Valignano) had constant need of an interpreter.

Despite their efforts to learn the language, early Jesuit priests converted very few locals. In an attempt to save the mission, Xavier switched his approach by choosing to preach to those individuals in society who held the most authority and riches, such as the local daimyo (lords). To do this, they mirrored the Buddhist's practice of donning radiant garment and employing an entourage. Such extravagances would certainly bring ire in Europe, however, in Japan, a show of opulence such as this was commonplace for religious organisations. Their plan succeeded, as when a daimyo converted, so did many of his subordinates. While many of these new converts did so out of genuine belief, others saw the opportunities that such a relationship with the nanban might bring through trade, especially as the use of firearms in regional conflicts became more commonplace.

Christianity Mistaken for Buddhism

As mentioned before, Xavier would often debate with Buddhist bonzes (monks), who would regard the Jesuits as being poverty-stricken, given their temperance for all that is lavish in the early stages. Records of these debates show that the Buddhist monks had some understanding of Christian theology and the intricacies of the Jesuits' religion, and they would rationally argue against them with Xavier. The missionary, holding the Japanese in high esteem for their intellect, mentioned that the Buddhist monks' intellectual capabilities had been hijacked by an evil force, as he believed that the bonzes' understandings about Christianity, and the world writ large, had been taught to them by the Devil.

Upon such an occasion, after describing his Christian faith, a monk replied that they held the same beliefs as one another, perplexing Xavier. Indeed, even the image of the Buddhist goddess Kannon with her child may have looked similar to that of the pictures of Mother Mary and baby Jesus that Xavier used when preaching to the people.

It did not help that the word Anjirō had chosen to call the Christian God was Dainichi – a word that could be misconstrued as simply another name for Buddha. On top of this, he had referred to the missionaries by a term that one may attribute to a Buddhist monk, and insisted that they originated from India – Buddha's homeland. This, combined with the Jesuits' inability to reliably and consistently communicate the belief structure of Christianity, made a large majority of the Japanese people dismiss Christianity as another Buddhist sect.

Within a decade, they sought to solve these problems by introducing new concepts and words, such as Deus (God). The ministers of Deus were not to be given the same names as Buddhist or Shinto priests – they were to be called padres, which the Japanese had trouble pronouncing, and so they settled on bataren. A follower of Christianity was called a Kirishitan, which included the Japanese kanji for happiness and prosperity. This was done in addition to them training up local interpreters, translating sacred text, and learning Japanese themselves.

Christian Schools & the Printing Press

In 1551, Xavier undertook a journey to Kyoto, seeking an audience with the Emperor of Japan to gain his approval of the missionaries' activities. However, upon his arrival, he discovered that the imperial court was closed to foreigners. Although his objectives were not met during this trip, later, Alessandro Valignano met shogun Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582), and the Japanese warlord gave his permission to the missionary to set up a Christian school in Azuchi. Valignano would set up many other schools across the country, in areas such as Nagasaki, Yamaguchi, and Kyoto, where students would be instructed on Christian teachings as well as general education.

The first printing press to arrive in Japan, brought by Valignano, was used to produce various forms of text in a number of languages, including Japanese. Local artisans were employed to create Japanese language printing blocks. The press was not only used to produce catechisms and Bibles but also educational texts in subjects such as mathematics and history.

At its height of popularity, Japan contained the largest number of Christians in the world outside Europe by the end of the 16th century. The popularity that the faith enjoyed in the country worried Nobunaga's successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), who took steps to stem its growth. Japan was embroiled in conflict, and social unrest was near constant. Such a situation might have seemed an easy opportunity for European powers to expand their colonial holdings. Additionally, Hideyoshi was aware of the difficulties in handling daimyo who had pledged their allegiance not to him, but to a foreign power (the Pope), as well as the threat that the newcomers may present to Japanese culture and norms.

Suppression & Persecution

After the consolidation of Japan under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan entered a period of isolation from the rest of the world and strict rules were implemented: Japanese were not allowed to leave Japan, and no foreigners, save for those with the bakufu's (government's) permission, were allowed to enter the nation. Even the Dutch, who were allowed to continue trading with the Japanese, were housed in a small, guarded island complex linked to Nagasaki. Earlier edicts suppressing the spread of Christianity were stringently upheld during this time, save for some outlying areas. Open displays of worship to Deus were forbidden, the penalty of which could include death.

To root out the believers from amongst the populace, the authorities required citizens to tread on a fumi-e: a wooden or metal block that bore a Christian image such as that of Jesus Christ or the Mother Mary. Those who would not place their foot on the image were outed as Christians. The bakufu would then attempt to sway these individuals from their beliefs. Should the Christians refuse to give up their faith, they would be tortured and eventually killed if they continued to resist.

Methods of torture and execution varied. A popular story is that of the 26 Martyrs of Nagasaki, several of whom were children, who were crucified. It is said that upon reaching their execution site, the condemned ran to and embraced the crosses that would bring about their agonising death. Another method was to collect the scalding hot water of an onsen and pour it directly on the skin of a Christian. When the Christians resisted this torture, they might be thrown into the onsen and left to drown in the burning pool.

Hidden Christians

To keep their faith secret, Kakure Kirishitan ("Hidden Christians") would often hide in plain sight: one might see the instrument of Christ's death in the cross-beam of a house, an image of the Mother Mary could be disguised as the Buddhist deity Kannon (who could also at times be shown holding a child), a stone lantern might have a Christian image chipped into it base, which would be covered by soil. Much like the lantern, hidden Christians had to project the image of a dutiful Japanese citizen on the outside, while their true beliefs remained hidden.

As the years went by, Christianity in Japan became increasingly diverse, with neighbouring villages having entirely different beliefs from one another while still professing to be of the same religion. Without the direction of the padres, and the hesitancy to write much down for fear of being caught, the elders would pass down the prayers, practices, and doctrines by word of mouth, and because Christians from across the land could not convene together, the elders' words were taken as truth.

Many of the descendants of those Japanese Christians who went into hiding still practice their faith in privacy today, not out of fear of the repercussions of being found out, but instead as a ritualistic undertaking where the act of secrecy is almost as important as the message the Gospel brought them.

The Shimabara Rebellion

The persecution of Christians in Japan boiled over in Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan's three main islands, culminating in the Shimabara Rebellion. Fuelled not only because of the bakufu's treatment of Christians but also by a recent famine and malevolent local daimyo, the inhabitants of Shimabara, and some surrounding areas (namely the Amakusa Islands), rose in a revolt. Supposedly led by a 16-year-old named Amakusa Shiro (or Jerome Amakusa), tens of thousands of rebels laid siege to castles and fought pitched battles against constabularies. The shogunate sent an outnumbering army to crush the rebels, forcing Jerome Amakusa and his followers to hold up in Hara Castle. The shogunate's forces, along with a Dutch ship and her sailors who had been asked to join, eventually wore down the defenders and breached the fortress. After a few days of slaughter, during which Jerome Amakusa was killed, the rebellion was ended.

So devastating was the loss of life that the bakufu had to repopulate areas of the region, leading to a diverse mix of cultures and customs that exist even today. The people were made to register themselves at local shrines and perform apostatising rituals. So eager were the locals to prove that they were not Christian that they left up seasonal religious decorations all year round, a cultural practice that still occurs today.

The rebellion affirmed the bakufu's belief that Christianity was a deviant and dangerous religion which left unchecked would lead to their downfall and possibly even colonisation, whether it be through force or conversion of the populace. Restrictions on the faith were further tightened and outward displays of Christianity that were usually tolerated by daimyo were almost entirely done away with.

Conclusion

Pressure from Western nations eventually forced the Japanese government to take action in 1873, when the Meiji authorities issued an edict of religious toleration that decriminalised the practice of Christianity. However, the number of believers whom at their peak numbered some 600,000 had dwindled to around 30,000. The Western churches rejoiced at the news of Christianity having survived under such harsh conditions, but, upon further investigation, they found that the religion practised by Japan's hidden Christians was very different from what Francis Xavier had brought to the country over 300 years prior. Such were the differences in belief, that many of the hidden Christians rejected the churches' doctrines, not wanting the beliefs of their forefathers to be forgotten. As such, the religious beliefs of the hidden Christians were more akin to Japanese folk religions than traditional Western Christianity.

Today, Japanese individuals who identify as Christian make up approximately 1-2% of the country. This may be attributed to the historical suppression of the religion, isolationist policies that ended in 1853, traditional Japanese religions and practices being tied to national identity, and Japan's rapid shift to urbanisation which often leads to secularisation.