The Battle of Gazala in Libya in May-June 1942 was a decisive victory for German and Italian forces led by General Erwin Rommel (1891-1944) against British, Commonwealth, and Free French forces during the Western Desert Campaigns (Jun 1940 to Jan 1943) of the Second World War (1939-1945). As a consequence of the defeat and breaking up of the British defensive line at Gazala, the Allies were obliged to surrender the key fortress port of Tobruk and give Rommel his finest victory.

Desert Warfare

Into the second year of WWII, the Allies, then principally British and Commonwealth forces, were keen to protect the Suez Canal from falling into enemy hands, that is into the control of the Axis powers of Germany and Italy. North Africa was also strategically important to both sides' wish to control and protect vital Mediterranean shipping routes. The island of Malta was also crucial in this role and holding the island fortress (then in British hands) was another reason to control potential airfields in the North African desert. Finally, North Africa was the only place where Britain could fight a land war against Germany and Italy and so hopefully gain much-needed victories that would encourage the British people after the debacle of the Dunkirk Evacuation and the horrors of the London Blitz.

For all of the above reasons, a series of desert battles ensued, which are collectively known as the Western Desert Campaigns. At first, the British Army faced poorly equipped Italian forces, but these were soon considerably boosted by German troops with superior armour, weapons, and training.

North Africa proved a difficult theatre of war with its small ports, poor (or often non-existent) roads, and harsh desert environment. For both sides, battling local conditions and overcoming frequent shortfalls in logistics became just as important as bettering the enemy's military forces. As Rommel once reflected: "The battle is fought and decided by the quartermasters before the shooting begins" (Mitchellhill-Green, 264).

One thing the desert had was space, and battles could range over many miles as territorial gains became much less important than inflicting material damage on the enemy compared to other theatres of the war. Other peculiarities of desert warfare included the general absence of any civilian involvement and the fact that both sides frequently used captured equipment, a phenomenon that often made positive identification of exactly who was approaching across the far horizon in clouds of dust and sand extremely difficult. These same dust clouds, and the speed of armoured engagements, also meant that both the Axis and Allied air forces could only play a limited role in battles and so were largely reduced to targeting supply lines or fixed defensive positions.

The Desert Fox

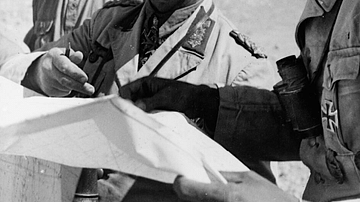

Generalleutnant (Lieutenant-General) Rommel was an advocate of fast mobile warfare using tanks, tactics he had employed to great effect as commander of a panzer division during the Fall of France earlier in the war. Appointed commander of the Deutsche Afrika Korps (DAK) in January 1941, Rommel would apply the same tactics of mechanized warfare in the Western Desert of North Africa. It was no coincidence that the Afrika Korps' war cry was Heia Safari, Swahili for "Let's go get 'em" (Dear 7).

Rommel used tanks in an unusual way. Instead of employing armoured vehicles to destroy the enemy's tanks, the typical approach of other armour commanders, Rommel used forces equipped with anti-tank guns to first disable as much of the enemy's armour as possible and only then did he engage his own tanks which made short work of the enemy's now unprotected infantry. Above all, Rommel favoured speed and audacity, tactics which greatly unsettled the much more cautious Allied commanders then in North Africa, commanders who very often preferred to wait until they had an overwhelming advantage in men and material before making a decisive move on the enemy.

Rommel captured El Agheila in March 1941 and then Mersa Brega on 1 April. By July, Rommel was in overall practical command of all German and Italian forces in North Africa (although he was still technically under the ultimate authority of the Italian high command). He was already establishing a reputation as the bogeyman and principal cause of havoc for the Allied forces in the region and had gained the nickname the Desert Fox. Two victories against Allied offensives in May and June (code-named Brevity and Battleaxe, respectively) were followed by defeat in a third offensive in November, code-named Crusader. Rommel's two main problems were insufficient manpower and a lack of supplies (especially food, fuel, and ammunition), but by January 1942, this situation improved significantly and the German general, ignoring his orders to emphasise defence, went on the attack once again.

Rommel's enemy came in the form of the British and Commonwealth Eighth Army, commanded in the early summer of 1942 by Lieutenant-General Neil Ritchie (1897-1985). The overall commander of Allied troops in the Middle East was General Claude Auchinleck (1884-1981). Unfortunately, at this stage of the Western Desert Campaigns, the British Army was not coordinating well between its infantry, artillery, and armoured divisions, nor were its reinforcements anywhere near the calibre of the core soldiers with desert war experience. A lack of battle drills, inferior armour such as the Crusader and Matilda tanks, inferior anti-tank guns, and a cumbersome and rigid chain of command were all defects which significantly hindered the Eighth Army. In contrast, "Rommel's force was numerically inferior, but his troops were more professional, better led, and thoroughly steeped in the cooperation of all arms" (Dear, 992).

The Gazala Line

Tobruk was crucial to any army wishing to advance into Egypt and Rommel made three failed attempts to take the port, which was stoutly defended by two Australian brigades. Both the Brevity and Battleaxe offensives failed to relieve the siege on Tobruk, and the Australians, ordered to withdraw by their government, were replaced by British Army troops, which included the 2nd South African Division and a Polish brigade. The Crusader offensive finally broke the siege in December 1941, but Rommel was determined to acquire this vital logistics hub. First, he quickly retook nearly half the territory lost in the Crusader offensive and then turned his attention to the Allied defensive line at Gazala, located 64 km (40 mi) west of Tobruk. An attack on the Eighth Army would also pre-empt a British offensive to push back Rommel in preparation for large-scale Allied landings across North Africa, planned for the following November. Both sides were aware of the other's plans thanks to military intelligence (and the obvious build-up of troops at Gazala), although Rommel's tendency to communicate one thing to his superiors and then do another meant the British were never quite sure what the Desert Fox was really up to.

The Gazala Line was a series of static defences composed of isolated strongpoints, each defended by a brigade, with tanks distributed in between and each strongpoint further protected by barbed wire, trenches, and a deep belt of minefields. The line, which stretched from Gazala to Bir Hakeim (aka Bir Hacheim), a remote outpost consisting of not much more than a seriously ruined fortress and a desert well, was designed to defend both the western approach to Tobruk and the Via Balbia road through Libya. There were no fortifications in the line, and most of the strongpoints were really designed as assembling platforms from which could be developed the planned offensive. The strongpoints could not mutually assist each other since they were too far apart, rather they were designed, if required, to hold the enemy until mobile armoured troops could relieve them. Like most defensive positions, the weakest points of the Gazala Line were the two flanks. Rommel's Operation Venezia aimed to exploit this very weakness. The Eighth Army had a numerical advantage, particularly in operational tanks – 849 against Rommel's 560 – but this superiority was negated by the need to spread out armour, men, and artillery over a long line of defence.

Rommel Attacks

The Battle of Gazala began on 26 May 1942. Rommel deployed his Italian troops to attack the most southern strongpoint of the Allied lines at Bir Hakeim. This end strongpoint was garrisoned by the 1st Free French Brigade under the command of Major General Marie Pierre Koenig (1898-1970). The force included two battalions of the famed French Foreign Legion and French colonial troops from Chad and Congo.

Rommel moved his armoured forces in an arc to attack the enemy from behind. At the same time, Italian troops attacked the Gazala Line front on, towards the northern end of the line, principally as a diversionary tactic to suck in as many Allied tanks as possible and so weaken the force opposing Rommel to the south. To enhance the illusion that the main Axis armour attack was taking place here and not to the south, Rommel had an armoured unit conduct a feint advance before it turned south, and he had trucks loaded with aircraft engines drive around to whip up as much dust as possible.

The surprise attack to the south, carried out at night to avoid the inevitable and tell-tale dust clouds, went well at first as the Axis forces raced at least 40 or 50 kilometres (25-30 mi) to their individual targets. However, the defences were stronger than Rommel had imagined, and the British were also now equipped with new and much more effective Grant tanks. The Allied commanders knew of Rommel's movements thanks to a South African armoured car unit, which had been following him from the start of the attack. The problem for the Allies was to decide which attack (the central or southern one) was the real one and which was the feint. By morning, it was clear the southern attack contained the bulk of the Axis armour.

After a series of bruising tank battles, and with his supplies of fuel and ammunition running low, Rommel withdrew on 29 May. The general noted in his diary: "Our plan to overrun the British forces behind the Gazala Line had misfired. The opposition was much stronger than expected" (Ford, 42). Ritchie thought that Rommel was giving up completely on the attack and did not immediately deploy a force to pursue the Axis forces that now gathered at a depression called the Cauldron located outside the minefields but central to the entire battlefield. Rommel was given time to resupply by the dithering of the British commanders, who were convinced they had the fox cornered and so there was no urgency to sending in their hounds. Meanwhile, Rommel was secure behind a screen of his own formidable 88-mm artillery units on one flank and, on another, the enemy's own minefields along with mines he himself had laid. Rommel's logistics lifelines were reopened following the clearing of paths through two minefields by two Italian motorized divisions and by the capture of the Allied Sidi Muftah and Dahar el Aslag strongpoints. Regrouped and refreshed, Rommel's troops repulsed a poorly coordinated British attack on the Cauldron on 5 June, and then the German general launched his own counterattack. Rommel also ordered a renewed offensive on Bir Hakeim, bolstering the Italian troops with a German Panzer battlegroup and throwing in air support in the form of 54 fighter planes and 45 bombers. Despite prolonged and heroic French resistance, the position was finally captured on 10 June, but not before 2,700 defenders had withdrawn from the original garrison of 3,600. The Battle of Bir Hakeim became the stuff of legend.

Rommel next attacked the British rear, inflicting heavy losses, and then overran the central British strongpoint called Knightsbridge, on the night of 12 June. The Eighth Army had lost over 140 tanks in just 24 hours. On 14 June, the British, fearful of its imminent capture, were obliged to destroy their major supply dump at Belhamed, which included 5.7 million litres of fuel. The British command structure, and indeed the whole Eighth Army, was a shambles. Three Allied divisions remained totally unused, a criminal waste of resources, which meant Rommel could pick off individual enemy formations, despite having a numerically inferior force overall.

Smashed in two places and with the British armour suffering increasingly heavy losses, the Gazala Line had ceased to be an effective defence. With Rommel gaining further victories against isolated pockets of Allied forces, the way to Tobruk was now open. The Battle of Gazala ended on 17 June. As the historian T. Moreman notes:

Eighth Army yet again had been out-generalled and out-fought by the Axis forces during three weeks of bitter battle...Ritchie and the British high command had effectively squandered the advantages with which it began the battle. (75)

Lieutenant General Francis Tucker, commander of the 4th Indian Division, described the defeat at Gazala as "one of the worst battles in the history of the British Army" (Mitchellhill-Green, 271).

Rommel surrounded Tobruk on 17 June and, with significant air support, captured the port on 21 June after attacking the least expected section of the defences; indeed, the port had been shorn of most of its defences for reuse in the Gazala Line. The Tobruk garrison surrendered, and 33,000 men were taken prisoner of war. Excepting the fall of Singapore, this was the largest capitulation made by the British Army in WWII. The fall of the port put much valuable supplies into the hands of the Desert Fox and provided him with half of his army's transport vehicles. Rommel then gained another victory at the Battle of Mersa Matruh, capturing the Egyptian port on 28 June. The Eighth Army, having lost 50,000 men but still a formidable force, now withdrew behind the defensive line at El Alamein, located further east along the Egyptian coast.

Aftermath

After the capture of Tobruk, Rommel was at the peak of his career, and, aged 49, he was promoted to Generalfeldmarschall (field marshall), making him the youngest holder of that rank in the German army at the time. Rommel managed to force the British Army out of Libya and back into Egypt. By striking at a weakened and demoralised enemy, Rommel hoped to capture the two great prizes of Alexandria and the Suez Canal, victories which would affect the entire war. However, in the longer term, Rommel's old problem of insufficient supplies and materials to achieve his tactical aims would once more give the British an advantage, one they used well at the First Battle of El Alamein in July 1942 and at the Battle of Alam Halfa the following August. The British army benefitted from air support provided by a much-enlarged Western Desert Air Force whose fighter and medium bomber squadrons could now operate much closer to their bases. In contrast, Rommel's air support dwindled the further east he moved and his logistics lines were also stretched to breaking point. Perhaps just as significantly, the British Eighth Army's new commander from August 1942 was General Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976), and he revitalised the force so that they earned their nickname of the Desert Rats (a name first applied to the 7th Armoured Division). Montgomery much more effectively combined artillery, infantry, and armoured divisions to inflict a heavy defeat on Rommel in October-November at the Second Battle of El Alamein, but, despite mopping up 30,000 prisoners, Rommel was permitted to withdraw to fight another day. Tobruk was then retaken by the Allies.

Three new Allied forces, which included the Western Task Force commanded by General George Patton (1885-1945), landed in North Africa in November 1942 and headed eastwards. Montgomery captured Tripoli in January 1943. Rommel realised the hopelessness of his position given the superiority of the enemy in terms of numbers and logistics, but his recommendation to the German high command that North Africa be abandoned went unheeded. Rommel, who had withdrawn his forces to Tunisia, was ordered to continue the desert campaign as best he could. The Allies were attacked in northern Tunisia and even defeated at the Kasserine Pass in February 1943. The British Eighth Army then won the Battle of Medenine (6 March 1943), and Rommel, by then quite ill, returned to Germany in March 1943; he would never fight again in Africa. Finally, the Desert Fox had been defeated by the Desert Rats. Allied ground and air forces combined with naval blockades of key ports to drive the Axis powers out of North Africa by May 1943.