The Medicine Arrows and the Sacred Hat is a short essay by anthropologist George Bird Grinnell (l. 1849-1938) explaining the origin and significance of the medicine arrows and buffalo hat, central to Cheyenne culture. The essay provides a backstory to the Cheyenne legends The Life and Death of Sweet Medicine and Old Woman's Water and the Buffalo Cap.

These two tales tell the stories of the Cheyenne culture heroes Sweet Medicine and Standing-on-the-Ground, who gave the gifts of the Four Sacred Arrows and the Buffalo Hat to the people long ago, establishing order and encouraging reverence for the Creator from whom these gifts had come. As Grinnell notes, in time the people failed to show proper respect for these objects – the Four Arrows were taken by the Pawnee in battle when the proper ceremony prescribed by Sweet Medicine was not observed, and the Buffalo Hat degraded owing to improper care by its keepers – and this failure was understood by the Cheyenne to be responsible for later misfortune.

Initially, the sacred objects were well cared for, and the proper rituals concerning them were observed. The passage of time and circumstance are said to have contributed to their loss, but, in the present day, the gifts of the culture heroes are again central to Cheyenne observances.

Culture Heroes & Sacred Objects

All Native American nations have their own culture heroes – people who serve as mediators, messengers, or even avatars of the Great Spirit – who bring significant gifts to the people at pivotal points in their history. Among the most famous of these is White Buffalo Calf Woman of the Lakota Sioux and Hiawatha of the Iroquois. In the Pawnee legend, Making the Sacred Bundle, Chief Eagle Feather plays the part of culture hero by establishing the tradition of the medicine bag, and among the Cheyenne, central figures include Falling Star, Ehyophsta (of the Ehyophsta Legend, not the 19th-century warrior woman), Sweet Medicine, Standing-on-the-Ground, and Erect Horns (the latter two sometimes replacing each other). Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman comments on the significance of these figures:

Once the world had come into existence, more accessible beings transformed it and made it habitable. These characters brought people light and fire and the tools and technologies of their traditional cultures: Sweet Medicine gave sacred arrows to the Cheyenne; Lone Man established the Mandan tradition of leaving a plaza in the center of the village in which to dance. These imposers of order (a popular activity is vanquishing the primeval world's monsters) are referred to by anthropologists as "culture heroes" – creative beings who transform their surroundings and themselves, while assuming human or animal characteristics and personalities in the process.

Heroes come in many forms and include the extraordinary activities of otherwise normal people. A hero might have been involved in the creation of human beings, have played a part in bringing new technology or belies to a group, or in saving the people from catastrophe. Heroes exemplify intelligence, generosity, and personal sacrifices made for the good of the group. Preserved in their basic structure, the stories of culture heroes are often adjusted to meet the needs of each generation.

(180-181)

Culture heroes – as well as their counterparts, the trickster figure – also exemplify transformation and the recognition of change as not only inevitable but desirable. In the case of Sweet Medicine, he was initially a troublesome trickster figure before recognizing the values of the Creator God Maheo (Wise One Above) and becoming a lawgiver and prophet to his people.

Culture heroes are frequently associated with sacred objects, and so it is with Sweet Medicine and Standing-on-the-Ground. Even if the people eventually fail to value these objects as they should – or as they once did – the "medicine" (the spiritual power) – of said objects does not diminish; it only becomes less accessible to those who need it. The "power object" remains imbued with the same spiritual energy whether one believes in that energy and honors it or rejects and ignores it. This same paradigm applies to the Four Arrows and Buffalo Hat of the Cheyenne as to any other sacred object.

Spiritual Power & Tradition

Medicine bundles – and the objects they hold – are not diminished by one's lack of belief in them or failure to care for them; those who do not honor them suffer for such lapses, and these are always due to a breakdown in observance of tradition, which is caused by a failure in following the instructions laid down by a culture hero. Native Americans understand the world as alive with spiritual energies that demand proper respect and the observance of rituals, performed in accordance with tradition, showing that respect. A given ceremony needs to be enacted precisely as it has always been – in the place where it had always been observed if possible – for it to be regarded as valid and acceptable to the spirits it is supposed to honor. Zimmerman comments:

Not only do landforms, plants, and animals have a spirit, they can actually be the spirit. An eagle is an eagle, but it can also be a thunderbird with special powers for protection; coyote is a coyote, but it can also be a manifestation of trickster, willing to lead a human or other animal astray or to teach them a lesson. It is imperative for people, who have to live alongside these multitudinous spirits, to know this and behave accordingly. If one obeys certain rules, there may be benefits; if one doesn't, there may be dire consequences. This concern with the spirits of nature does not in any way mean that either the spirit or nature is venerated; rather, nature is praised at the same time that one lives with and uses these invisible powers. Elders teach children about how to deal with nature spirits, in the hope of ensuring proper respect. Some individuals seek to harness and direct the power, or "medicine" – normally in a modest way – perhaps by using a talisman in a medicine bag or a bundle.

(86)

This concept is exemplified by the Four Arrows and the Buffalo Hat: the spiritual power is inherent in the objects, but it is not accessible unless one performs the proper ritual in faith and in accordance with the instructions that have come to form the traditions surrounding that ceremony.

The Four Arrows & the Buffalo Hat

A common theme in Native American legends – as well as accounts of historic events and figures – is the danger inherent in a failure to follow simple instructions or perform ceremonies in accordance with tradition. One famous example of this is the death of Roman Nose (Cheyenne Warrior) (l.c. 1830-1868), who neglected to perform his protective ritual before the Battle of Beecher Island and was killed. Many of the Wihio Tales of the Cheyenne – and the Iktomi Tales of the Lakota Sioux – as well as similar trickster stories of many nations – warn of the danger in failing to observe traditions, and this is the same case with the Four Arrows and the Buffalo Hat.

As Grinnell explains below, the Four Arrows were lost in battle against the Pawnee in 1830 after a failure to observe the proper ceremony concerning them, and, although various sources differ on the final outcome, it does not seem all four of the original arrows were ever regained. The Cheyenne had arranged themselves for battle to surprise the Pawnee camp, that summer of 1830, when they were discovered by Pawnee buffalo hunters. The ceremony of the Four Arrows had not even begun, but there was no time for it once the battle began, and so Chief White Thunder of the Cheyenne handed the four arrows to the warrior Bull to carry them into battle. Since there had been no ceremony accessing the power of the arrows, however, their protection was neutralized, and the Cheyenne were defeated, losing their sacred bundle of arrows to the Pawnee who then refused to return them.

Grinnell's brief narrative on the fate of the Buffalo Hat follows a similar model in that the keepers of the hat do not seem to intend any disrespect to purposefully cause the degradation of the hat, but still, through a failure to observe the traditional ceremonies, the hat falls into disuse and disrepair. The loss of these sacred objects, as noted, was then blamed for Cheyenne misfortune including defeat in battle, massacres of the elderly, women, and children by the US army or enemy Native nations, and the loss of Cheyenne lands through the double-dealing of representatives of the US government.

As the Cheyenne, like other nations, have succeeded in fighting for and demanding their rights as an autonomous people, these once-sacred objects have again come into focus. Whether the arrows held by the Cheyenne today are the same arrows said to have been given them by Sweet Medicine is challenged, as is the case with the Buffalo Hat, but the spiritual powers these objects represent continue to be honored through ritual today just as they were in the distant past.

Text

The following text is taken from By Cheyenne Campfires (1926) by George Bird Grinnell. The story of the Four Arrows and Buffalo Hat was most likely translated for Grinnell by the Anglo-Cheyenne interpreter and historian George Bent (l. 1843-1918), who was responsible for translating most if not all of the communication between Grinnell and the Cheyenne.

In the different war stories, frequent mention is made of the medicine arrows and buffalo hat, two protective mysteries long possessed and greatly reverenced by the Cheyenne. These were brought to them by the culture heroes of the two tribes, sent by the Great Power to insure to the people health, long life, and abundance in time of peace, and protection, strength, and victory over their enemies in war.

The medicine arrows were brought to the Tsistsistas by Sweet Medicine, and the buffalo hat to the Suhtai by Standing-on-the-Ground. The arrows were four in number, with stone points as in the ancient times, and the sacred hat is a cap or bonnet made of the skin of the buffalo cow's head, ornamented by a pair of buffalo horns shaved down, flattened, and decorated.

The arrows were in charge of a special man who, when he supposed he was about to die, handed them over to be cared for by some man of his family – his younger brother, or his son, or perhaps his nephew. The arrow keepers were men of wisdom and of power and were respected advisers in the tribal affairs. In the same way, the sacred hat was in charge of a chosen man, from whom it passed on to another, usually a relative, and from him to another.

From time to time, occasions arose when it was necessary to renew the arrows, by which was meant taking the four arrows from their bundle, perhaps removing the stone points from the shafts, replacing them with fresh winding of sinew, and putting new feathers on the shafts. There were various reasons for this renewing the arrows; sometimes it was performed as a sacrifice or an atonement for a wrong done; sometimes to ward off a feared misfortune; sometimes to end an existing evil; and sometimes as the payment of a vow. Some man must have pledged himself to do this renewing and it was a difficult and a costly sacrifice to make. If in the camp an individual killed one of his tribesmen by accident or design, the arrows must be renewed. If inspected after such an event the arrows all showed little specks of blood on the heads. Sometimes such marks on the arrows were seen when no one had been killed and, in that case, it was thought either that someone was about to be killed or else that a great sickness threatened the camp.

When the arrows were to be renewed, all the divisions of the tribe, which might be scattered out in many different groups and places, were summoned to come into the main camp and there to remain during the four days that were occupied in the ceremony. All the people were usually glad to come, for they would be benefited by the ceremony, the good influences of which were helpful to all in the camp.

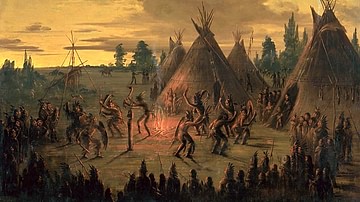

Sometimes, in order to be revenged for injuries inflicted by enemies, the whole tribe, men, women, and children, set off to war and, on such an occasion, took with them the medicine arrows and buffalo hat. To ensure the success of such a war journey, it was necessary that these sacred objects should be treated in a special ceremonial fashion. If not so treated, their protective help was lost. So long as proper reverence was paid to them, and the ceremonies performed which the culture heroes had prescribed, it was believed that these mysteries would protect the tribe from harm.

It was the law that, when these two sacred objects were taken to war by the tribe as a whole, a certain ceremony must be performed before the enemy was attacked. Before this, two young men were chosen to carry these things into battle, one to carry the arrows and the other the sacred hat. Before they were given to these men, the ceremony, which was part of the ritual of these objects, was performed. It was intended to confuse and to alarm the enemy. Before the attack was to be made, the arrow keeper took in his mouth a bit of the root that is always tied up with the arrows, chewed it fine, and then blew it from his mouth first toward the four points of the compass and, finally, toward the enemy. This blowing toward the enemy was believed to make them blind.

After this had been done, the arrow keeper took the arrows in his hand and danced, pointing them toward the enemy, and thrusting them forward in time to his dancing. Drawn up in line behind the arrow keeper stood all the men of the tribe, each one standing as the arrow keeper stood, with the left foot forward, dancing as he danced, and making with their lances, arrows, or whatever weapons they might hold, the same motions toward the enemy that the arrow keeper made with the medicine arrows

The arrow keeper thrust the arrows four times in the direction of the enemy and a fifth time he directed them toward the ground. After he had gone through this ceremony, and sung the songs which go with it, the man chosen to carry the arrows into the battle went to the arrow keeper, who tied the bundle of arrows to the young man's lance. He who was to wear the sacred hat took that up from the ground and put it on his head, securing it there by means of a string which passed under his chin. The two men then mounted their specially chosen swift horses and rushed toward the enemy, riding ahead of the line of fighting men. When the two had come close to the enemy, each turned toward the other, and they crossed each other in front of the charging line, and then passed around behind it. This method of riding was supposed to blind, confuse, and frighten the enemy.

All these operations should be performed before any attack was made on the enemy; yet it frequently happened that young men, eager to gain personal glory for themselves, did not wait for these ceremonies to be completed but stole off to attack the enemy independently. If this attack was made before the ceremonies were completed, the act took away the power of the arrows and of the hat, their spiritual power was neutralized, and the Cheyenne were very likely to be defeated. This explanation seems necessary, in view of various allusions made to the arrows and the hat in the war stories [told by the Cheyenne].

Long ago, in the year 1830, the Cheyenne and the Skidi Pawnee had a great battle on the head of the South Loup River in Nebraska and, in this battle, the Cheyenne lost their medicine arrows, which were captured from them by the Pawnee. At a much later date, there was a dispute in the tribe over the guardianship of the sacred hat, and a lack of reverence was shown the object by Broken Dish, who had it in his possession, and by his wife, who removed and kept in her possession one of the horns attached to it. The capture of the arrows by the Pawnee and the failure to treat the sacred hat with respect are supposed to have brought to the Cheyenne many of the misfortunes which came to them in the latter half of the last century.

It is not known that any white man has ever seen the medicine arrows or the complete sacred hat. With the passing of the older generations, the importance of these objects has grown much less.