The Battle of Kasserine Pass in Tunisia (18-22 February 1943) was won by Axis German and Italian forces led by field marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944) against a combined Allied army of British, French, and US troops. The last fling of the famed Afrika Korps, Kasserine proved to be an inconsequential victory as the Allies rallied in force and definitively pushed the Axis armies out of North Africa just a few months later.

Operation Torch

The Allies (the United States and Britain and its empire) were keen to open a second front in Europe against Germany and Italy but first had to secure North Africa, which could provide a platform for an invasion of Italy. The Western Desert Campaigns had been swinging back and forth across the desert since 1940. Finally, the pendulum was ceasing to swing, beginning with the success of the British Eight Army at the Second Battle of El Alamein (October-November 1942) and followed up a few days later by Operation Torch, a massive amphibious and air operation, which landed three Allied armies in French Morocco and Algeria. As the British Eighth Army led by General Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976) moved in from the east and the Allied army (US, British, and French forces) of Torch commanded by Lieutenant-General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) moved from the west, the Axis armies were reduced to holding a pocket in northern Tunisia. Without sufficient supplies, the Axis field marshal Erwin Rommel recommended to the leader of Nazi Germany Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), who was then wholly preoccupied with the Russian Front, that North Africa be abandoned. Rommel's advice was ignored, and he was ordered to continue the desert campaign as best he could. Aid did arrive in the form of 17,000 fresh Axis troops, who landed via Tunis through November. These reinforcements and an increase in the power of the German air force in the region, allowed the Axis armies to successfully defend their position in Tunisia at Longstop Hill (22-25 December).

The progress of the Allies was being seriously hampered by poor weather and the logistical problem of supplying the Eighth Army through the extensive minefields at El Alamein. Montgomery, too, was particularly careful to ensure the enemy could not push his army back at any point as it slowly advanced. In any case, as time pressed on and 1943 began, the Allies were only growing stronger in troop numbers and material as these poured into the multiple ports they controlled. The Axis army was gaining in strength, too, but was far from equal to that of the Allies. Allied air and sea superiority continued to ensure Axis supplies to North Africa were continuously in peril. In January 1943, 31 of the 51 Axis supply ships destined for Tunisia were sunk or damaged. Through January and February, the Axis powers lost 200,000 tons of shipping destined for Tunis.

Opposing Forces

There were two Axis armies, one in the west directed by Field Marshal Albert Kesselring (1885-1960) and ultimately led in the field by General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim (1889-1962), and the other in the east led by Rommel. In order to prevent the Allies from driving a wedge between these two armies and to protect the vital port of Tunis, the Axis commanders decided to launch a counterattack. Just when the Allied commanders thought that North Africa was almost in the bag, this counterattack pricked many an inflated ego and cost the lives of thousands of inexperienced soldiers.

First to feel the brunt of the Axis offensive were the French divisions in the Eastern Dorsale mountains. These troops were poorly equipped with weapons inferior to those of the Axis forces bearing down on them led by Arnim. From 18 January, the Axis army swept all before them and easily gained control of the Eastern Dorsale passes. Arnim pushed on to capture Sidi Bou Zid and Sbeitla. Rommel was by now also moving on the offensive and he captured Gafsa. All of a sudden, the North Africa Campaign sparked into life again. In the space of 48 hours, the Allies had lost the initiative, and with it, six battalions. Rommel's master plan was to smash the weakened Allies in the west before turning to face Montgomery once again in the east, allowing the Axis powers to keep a sufficient toehold in Africa that would prevent or at least delay an invasion of Italy.

When the Allied commanders realised the Axis armies were in the midst of a major offensive, they withdrew to the safety of the Western Dorsale mountains, thus protecting their previously exposed flank. As in the east, there are several passes through these mountains, and so the Allies positioned troops in all three to deter the enemy. The force selected for the task of protecting the Kasserine Pass was the reserves of the 2nd US Corps commanded by Lieutenant-General Lloyd Fredendall (1883-1963). This motley unit was composed of elements of the 26th US Infantry Division, the 19th US Combat Engineer Regiment, the 33rd US Field Artillery Battalion, the 805th US Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the French 67th African Artillery. Most of these troops had very little or no battle experience, and their debut in the Second World War was to prove a literal baptism of fire. Arriving at the pass on 18 February, the US troops hurriedly prepared their defences, laid minefields, and dug foxholes where they could try to avoid the initial phase of the coming battle: an air attack by the dreaded Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers.

Rommel split his army in two, leaving most of the Italian element to defend his rear against the oncoming Eighth Army at the Mareth defensive line in the south of Tunisia. The German troops that Rommel commanded were experienced and battle-hardened veterans of the famed Deutsche Afrika Korps (DAK) along with elements of the well-equipped 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions. The German army in Tunisia did have a number of the new Pzkw VI Tiger tanks, each sporting a brutal 88mm gun, protected by armour four inches (10 cm) thick, and capable of outranging any Allied tank. Unfortunately for Rommel, getting these tanks to Kasserine proved problematic. At least the Axis air force in Tunisia had been significantly bulked up with new versions of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter plane to take its operational strength to 81 fighters and 28 dive bombers, wholly inadequate to face the Allied air force, but strong enough to cause some serious damage if used in concentration at the right time and place.

In the end, the battle of Kasserine Pass involved three separate attacks by the Axis forces, but the lack of coordination between them would be telling. Rommel had planned to break through the Allied lines in one place (Kasserine), smash the enemy army, using surprise and speed, and then push on for a full follow-up that ensured there would be no retreat to fight another day. As it turned out, the field marshal was left hamstrung by his orders. The Italian high command (in effect, Rommel's direct superiors) ordered Rommel to attack both the Kasserine and the Sbiba Passes. This would split the Axis force and not allow Rommel's best panzer divisions to support each other. Rommel had no choice but to try and achieve both objectives.

Rommel's Breakthrough

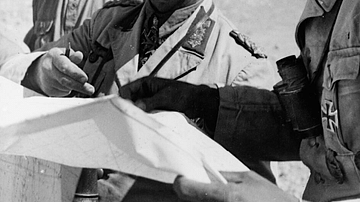

The German force attacked the approach to the Kasserine Pass on 19 February. Rommel, as usual, led from the front. One of Rommel's aides, Captain Alfred-Ingemar Berndt, recalls the effect of the field marshal's presence:

It was wonderful to see the joy of his troops during the last few days, as he drove along their columns. And when, in the middle of the attack, he appeared among the 10th Panzer Division right up with the leading infantry scouts in front of the tank spearheads, and lay in the mud among the men under artillery fire in his old way, how their eyes lit up. What other commander has such a wealth of trust to draw upon.

(Clark, 218)

The fighting was one-sided. The first strategic error of the Allies was to assume that the area was too mountainous for Rommel to effectively use his tanks, and so they were caught by surprise. The significance of Rommel's nickname as the 'Desert Fox' clearly eluded the American commanders, but the British on the other side of Tunisia could have told them from their long hard experience that if one could expect one thing of Rommel, it was to expect the unexpected. The second error was placing the main Allied reserve force, led by Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson, too far north. This deployment was based on a misinterpretation of secret military intelligence gathered from the enemy. The third error was to order the troops at Kasserine to defend the pass at all costs. A fourth error was allowing the Allied command structure to become so complicated that few men on the ground knew who was supposed to be doing what and where.

The German tank crews were highly experienced, and this meant they could fire much more rapidly than their novice enemy was capable of. Heinz Schmidt describes his unit's encounter with US Sherman tanks:

Beyond the minefield the road began to climb again. I was rounding a sharp curve when I sighted and recognized a Sherman tank on the road ahead, within attacking range. I jerked the wheel in the driver's hand and the vehicle swerved sharply towards the left bank of the road. The detachment manning the gun immediately behind me were swift in taking their cue. In a matter of seconds they had jumped from their seats, unlimbered, swung round and fired their first shell, while the Americans still stood immobile, the muzzle of the tank gun pointing at a hillock half-right from us. Our first shell struck the tank at an angle in the flank. The tank burst into flames.

(Strawson, 218-19)

As night fell on the first day of the battle, the Allies, still managing to hold on to the Kasserine Pass, received welcome reinforcements in the form of the 6th US Armored Infantry Regiment and a composite British force from Thala, which included artillery. From the second day of the battle, the area was hit by rainstorms, which impeded the vehicles and air forces of both sides. Meanwhile, in the Sbiba Pass, the Allied resistance by US and British troops was much stronger than Rommel had anticipated, the minefields and anti-tank gun units proving themselves formidable obstacles throughout the day of 19 February. If Rommel was going to achieve a victory, it would have to be in the Kasserine Pass.

On 20 February, Rommel pushed the Allied force back 50 miles (80 km) right through the Kasserine Pass. The Axis commanders still remained far less in tune than their tank crews, with Arnim refusing to send a panzer division to aid Rommel's push and only committing a battle group which, crucially, did not include the newest Tiger tanks. Even worse, the Italian high command now wanted to attack the Allied reserves at Le Kef. This was a good target but it would only have a short-term effect since the Allies could easily resupply their forces from elsewhere. Rommel described the decision to go for Le Kef as "an appalling and unbelievable piece of shortsightedness" (Dear, 637).

As a result of the new orders, by the end of the day on 20 February, the Axis front had two main prongs: one heading towards Tebessa and the other towards Thala. By now, though, the Allied commanders were fully aware of where Rommel was attacking and appropriate reinforcements were sent there in large numbers. The sheer scale of resources the Allies could call upon became clear to Rommel who now appreciated that, in the longer term, there could be no hope of victory: "In fact, their armament in antitank weapons and armoured vehicles was so enormous that we could look forward with but small hope of success to the coming mobile battles" (Allen Butler, 433).

On 22 February, Rommel, after realising the terrain and weather were doing no favours to his armour, and upon receiving news that Montgomery had finally reached the Mareth Line, called off his attack. The increasing Allied resistance as more reinforcements came in, the effectiveness of the Allied air power, the surprising accuracy of the US and British artillery fire, the particularly robust resistance around Sbiba, and the failure of Arnim and his 5th Panzer Army to fully support Rommel's plan were all additional factors in the field marshal's decision to end the battle while he was ahead. Rommel certainly pointed the finger at Arnim, blaming the lack of total success in crushing the enemy on "clumsy leadership by certain German commanders" (Boatner, 464). On 23 February, the Axis force began to withdraw from the mountain passes.

Aftermath

Rommel may have won yet another battle, but the consequences of the Allied defeat at Kasserine were not significant for the campaign in North Africa as a whole. Indeed, the pass was retaken on 24 February. Around 6,000 US troops were killed or wounded in the battle (Holland, 572), but the Axis armies suffered similar casualties, losses they could not replace as easily as the Allies. 3,000 US soldiers were taken prisoner of war in something of a propaganda coup.

The Allies lost the battle, but invaluable lessons were learned – the chief intelligence officer was replaced for a start, and battle-training methods were improved. The defeat, particularly for the untried US troops, was a serious blow to their confidence. Perhaps most significantly of all, Eisenhower replaced Fredendall with General George Patton (1885-1945), an altogether more able, confident, and aggressive commander, who was determined to make his mark on the war. Patton summarised his philosophy of always to attack the enemy by stating "Hold them by the nose and kick them in the rear" (Dear, 677). Meanwhile, the Axis forces continued at a disadvantage in that they were not fully supported by those at the very highest level. As General Walter Nehring ruefully noted, "Our military operations in North Africa were only of secondary interest to Hitler, who was concerned mainly with the hard war against Russia. Finally the German forces in North Africa were only a lost lot sacrificed by Hitler" (Holmes, 261).

The British Eighth Army led by Montgomery attacked the Mareth Line in March. The Axis army there was now led by Marshall Giovanni Messe (1883-1968) since Rommel had been promoted to commander-in-chief of Group Africa. On the other side, the efficiency of the Allied command structure was greatly improved by the appointment of the experienced General Harold Alexander (1891-1961), effectively Eisenhower's deputy and the commander in the field of all Allied forces in North Africa. The Allies won the Battle of Medenine (6 March 1943), and Rommel, who was seriously ill, returned to Germany in March 1943; he would never fight again in Africa. Axis forces, lacking sufficient supplies and material thanks to a tight naval blockade, were entirely driven out of North Africa by May 1943. The Allied victory in North Africa finally secured a platform from which they could attack Axis-occupied Europe through Italy, what British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) had described as "the underbelly of the Axis" (Holland, 430). The Second World War was about to enter a new phase as new theatres of conflict opened up.