The Girl Who Climbed to the Sky is a folktale from the Arapaho nation about a girl, Sapana, who is tricked by a supernatural sky-being into traveling to his home, where he keeps her, and then must find a way to return to her people, helped by the buzzard and the hawk.

The story is nearly identical to the first part of the Cheyenne legend of Falling Star in which a young maiden climbs an ever-growing tree in pursuit of a porcupine and finds herself in the sky realm, unable to return to earth. In that story, the young woman dies trying to escape, but her son, Falling Star, is rescued and raised by the meadowlark, finally returning to his people as a great champion. In the Arapaho story, Sapana is rescued by the birds who hear her cry and come to her aid.

The Girl Who Climbed to the Sky deals with many themes common in Native American literature including devotion to a cause and determination (exemplified in Sapana's pursuit of the porcupine), things not being what they seem (the porcupine is actually a sky-being), and the importance of one's home. The tale also serves as an origin myth explaining why the Arapaho always left food for the buzzard and hawk after a buffalo hunt. The story is still among the most popular Arapaho tales, is also told by citizens of the Caddo nation, and is frequently included in anthologies.

Cheyenne, Arapaho, & Bird Figures

It is not surprising that the Cheyenne Falling Star and the Arapaho The Girl Who Climbed to the Sky share similarities as the two nations were – and still are – closely related. The Cheyenne and Arapaho allied against common enemies in the early 19th century, and, although they were different nations, they had, and have, many cultural aspects in common. Scholar Adele Nozedar comments:

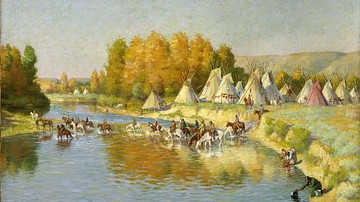

When the settlers first came upon them, the Arapaho were already expert horsemen and buffalo hunters. Their territory was originally what has become northern Minnesota, but the Arapaho relocated to the eastern Plains areas of Colorado and Wyoming at about the same time as the Cheyenne; because of this, the two people became associated and are also federally recognized as the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. (25)

It is unclear where the name Arapaho originated, but it seems to have been given to the people by European colonists who mispronounced the name given them by the Crow – Alappaho ("Many Tattoos") – and then the Arapaho began to refer to themselves by that name. They called themselves Hinono'eino ("the people" or "our people"), and the Cheyenne called them Hitanwo'iv ("People of the Sky"). After forming their alliance, the Arapaho and Cheyenne intermarried, and their histories became entwined. As Nozedar observes, their close relationship is recognized today by the US government, but it should be noted that they are distinct nations, each with their own culture, religious rites, and stories.

In regards to religion, the Arapaho have acquired the reputation of being more spiritually oriented and introspective than other nations, which has led some writers to make sharp distinctions between them and the Cheyenne. Scholar Michael G. Johnson, for example, comments, regarding the two in the 19th century:

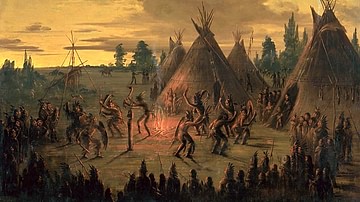

The Arapaho were often noted for their religious and contemplative disposition, less warlike than the Cheyenne. They were a nomadic equestrian people, hunting bison, developing military and age-graded organizations, and observed the Sun Dance. (119)

While Johnson's observation on the religious disposition of the Arapaho is accurate, the other aspects listed apply equally to the Cheyenne. The Cheyenne also had military societies, hunted bison, had age-graded organizations, observed the Sun Dance, and were no more "warlike" than the Arapaho. The Cheyenne Creation Story and Arapaho Creation Story also have much in common. The differences between the Cheyenne and Arapaho, though marked, are not as great as their similarities, and this is evident in their literature, which features common themes and figures, including birds.

Birds frequently appear in the tales of all Native peoples of North America and often as helpers, messengers from the gods, and guides. The use of birds in stories, lore, legend, and ritual prayer is not at all unique to the Cheyenne and Arapaho, but there is a familiarity between birds and humans in the stories of both nations that, generally speaking, seems warmer than the same relationship given in the stories of the Sioux or Pawnee or Cherokee or other nations.

Twelve Stories of the Plains Indians

In Falling Star, it is a meadowlark who saves the hero and raises him, and in The Girl Who Climbed to the Sky, it is the buzzard and the hawk, and in both, the birds are presented more as family members, helpers, than as spiritual guides or messengers. Like family members – in theory at least – they may not always be able to save or even help a person, but they are always there to lend what help they may. In Falling Star, the meadowlark is unable to save the maiden but raises her son. In The Girl Who Climbed to the Sky, the buzzard is presented as a friend and helper, but it is not always depicted that way in Native American literature. Vultures are sometimes portrayed as "helpers" who dispose of the dead and clear away waste but, often, are seen as bad omens symbolizing death or disaster.

Text

In The Girl Who Climbed to the Sky, however, the buzzard is given as a heroic helper, as is the hawk. The hawk was generally regarded as a positive symbol but could also be understood as a threat. In presenting both as positive figures, the story emphasizes the concept of things not always being as they appear or are understood. The same is true of the porcupine – usually presented as a positive symbol – revealed as a deceptive sky-being who kidnaps Sapana. Even the tree Sapana climbs emphasizes this concept of reality vs. illusion as it grows higher and higher as she climbs, finally bringing her to the realm of the Porcupine Man, where she becomes imprisoned.

It is also interesting to note the reason Sapana pursues the porcupine. Porcupine quills were sewn into the clothing and footwear of the Arapaho as spiritually potent protection of the wearer against harm and an assurance of their continued well-being. Sapana is, therefore, not pursuing the porcupine for her own ends, but for the good of others, further emphasizing an Arapaho value – also held by other nations – that the good of the community is of greater importance than the good of the individual.

The following text is taken from Indigenous Peoples' Literature compiled by Glenn Welker:

One morning several young women went out from their tepee village to gather firewood. Among them was Sapana, the most beautiful girl in the village, and it was she who first saw the porcupine sitting at the foot of a tall cottonwood tree. She called to the others: "Help me to catch this porcupine, and I will divide its quills among you."

The porcupine started climbing the cottonwood, but the tree's limbs were close to the ground and Sapana easily followed. "Hurry," she cried. "It is climbing up. We must have its quills to embroider our moccasins." She tried to strike the porcupine with a stick, but the animal climbed just out of her reach.

"I want those quills," Sapana said. "If necessary, I will follow this porcupine to the top of the tree." But every time that the girl climbed up, the porcupine kept ahead of her.

"Sapana, you are too high up," one of her friends called from the ground. "You should come back down."

But the girl kept climbing, and it seemed to her that the tree kept extending itself toward the sky. When she neared the top of the cottonwood, she saw something above her, solid like a wall, but shining. It was the sky. Suddenly she found herself in the midst of a camp circle. The treetop had vanished, and the porcupine had transformed himself into an ugly old man.

Sapana did not like the looks of the porcupine-man, but he spoke kindly to her and led her to a tepee where his father and mother lived. "I have watched you from afar," he told her. "You are not only beautiful but industrious. We must work very hard here, and I want you to become my wife."

The porcupine-man put her to work that very day, scraping and stretching buffalo hides and making robes. When evening came, the girl went outside the tepee and sat by herself wondering how she was ever to get back home. Everything in the sky world was brown and grey, and she missed the green trees and green grass of earth.

Each day the porcupine-man went out to hunt, bringing back buffalo hides for Sapana to work on, and in the morning while he was away it was her duty to go and dig for wild turnips. "When you dig for roots," the porcupine-man warned her, "take care not to dig too deep."

One morning she found an unusually large turnip. With great difficulty she managed to pry it loose with her digging stick, and when she pulled it up she was surprised to find that it left a hole through which she could look down upon the green earth. Far below she saw rivers, mountains, circles of tepees, and people walking about.

Sapana knew now why the porcupine-man had warned her not to dig too deep. As she did not want him to know that she had found the hole in the sky, she carefully replaced the turnip. On the way back to the tepee she thought of a plan to get down to the earth again. Almost every day the porcupine-man brought buffalo hides for her to scrape and soften and make into robes. In making the robes there were always strips of sinew left over, and she kept these strips concealed beneath her bed.

At last Sapana believed that she had enough sinew strips to make a lariat long enough to reach the earth. One morning after the porcupine-man went out to hunt, she tied all the strips together and returned to the place where she had found the large turnip. She lifted it out and dug the hole wider so that her body would go through. She laid her digging stick across the opening and tied one end of the sinew rope to the middle of it. Then she tied the other end of the rope about herself under her arms. Slowly she began lowering herself by uncoiling the lariat. A long time passed before she was far enough down to be able to see the tops of the trees clearly, and then she came to the end of the lariat. She had not made it long enough to reach the ground. She did not know what to do.

She hung there for a long time, swinging back and forth above the trees. Faintly in the distance she could hear dogs barking and voices calling in her tepee village, but the people were too far away to see her. After a while she heard sounds from above. The lariat began to shake violently. A stone hurtled down from the sky, barely missing her, and then she heard the porcupine-man threatening to kill her if she did not climb back up the lariat. Another stone whizzed by her ear.

About this time Buzzard began circling around below her. "Come and help me," she called to Buzzard. The bird glided under her feet several times, and Sapana told him all that had happened to her. "Get on my back," Buzzard said, "and I will take you down to earth."

She stepped on to the bird's back. "Are you ready?" Buzzard asked.

"Yes," she replied.

"Let go of the lariat," Buzzard ordered. He began descending, but the girl was too heavy for him, and he began gliding earthward too fast. He saw Hawk flying below him. "Hawk," he called, "help me take this girl back to her people."

Hawk flew with Sapana on his back until she could see the tepee of her family clearly below. But then Hawk began to tire, and Buzzard had to take the girl on his back again. Buzzard flew on, dropping quickly through the trees and landing just outside the girl's village. Before she could thank him, Buzzard flew back into the sky.

Sapana rested for a while and then began walking very slowly to her parents' tepee. She was weak and exhausted. On the way she saw a girl coming toward her. "Sapana!" the girl cried. "We thought you were dead." The girl helped her walk on to the tepee. At first her mother did not believe that this was her own daughter returned from the sky. Then she threw her arms about her and wept.

The news of Sapana's return spread quickly through the village, and everyone came to welcome her home. She told them her story, especially of the kindness shown her by Buzzard and Hawk.

After that, whenever the people of her tribe went on a big hunt, they always left one buffalo for Buzzard and Hawk to eat.