The Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781) was the final major military operation of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). It resulted in the surrender of British general Lord Charles Cornwallis, whose army had been trapped in Yorktown, Virginia, by George Washington's Franco-American army on land, and by Comte de Grasse's French fleet at sea.

War Comes to Virginia

In the spring of 1781, as the American War of Independence approached its sixth year, the British came to Virginia. 1,500 British troops under the command of the American turncoat Benedict Arnold landed at Portsmouth in January, going on to capture and burn the city of Richmond. Arnold was joined two months later by 2,300 more men under Major General William Phillips; together, Phillips and Arnold defeated a Virginia militia force at Blandford in late April before going on to burn the tobacco warehouses at Petersburg. They remained in Petersburg as they awaited the arrival of Lord Charles Cornwallis, who was marching up from North Carolina with 1,500 men, the survivors of the costly British victory at the Battle of Guilford Court House. Cornwallis reached Petersburg on 20 May, several days after General Phillips had died of a fever. Arnold returned to New York in June, leaving Cornwallis in sole command of the combined British army, which numbered over 7,200 men.

Cornwallis was not supposed to be in Virginia. Indeed, Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British forces and Cornwallis' superior officer, had ordered him to merely suppress Patriot resistance in the Carolinas. A task that had, at first, appeared easy enough soon turned into a quagmire, as Patriot and Loyalist militias tore each other to bloody shreds in the South Carolinian backcountry. All the progress Cornwallis had made in pacifying the country quickly unraveled after two defeats at the Battle of Kings Mountain and the Battle of Cowpens. Even his eventual victory at Guilford Court House left a bitter taste in his mouth, as he had lost over 25% of his army and had allowed the elusive American general Nathanael Greene to slip through his fingers. It was clear that his strategy would have to change if he wanted to win the South, no matter General Clinton's orders. His solution had been to invade Virginia. Greene and the Carolinian militias counted on supplies and reinforcements from the Old Dominion; should Virginia fall, Cornwallis calculated the rest of the South would fall with it.

Now, with the strength of Arnold's and Phillips' armies added to his own, Cornwallis put his plan into motion. He first struck toward Richmond, sending a small American army under Gilbert du Motiers, Marquis de Lafayette, running, before dispatching raiding parties into Virginia's heartland to seize supply depots and disrupt lines of communications. Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton and his dreaded British Legion were sent to Charlottesville, where Governor Thomas Jefferson and the Virginia General Assembly had relocated after the burning of Richmond; warned of Tarleton's coming, Jefferson and all but seven of the legislators managed to escape into the mountains mere minutes before 'Bloody Ban' arrived to apprehend them. Finally, on 25 June, Cornwallis' main army arrived triumphantly in Williamsburg. It might have been the start to a glorious conquest – had Cornwallis not received fresh orders from General Clinton the very next day.

The orders were for Cornwallis to suspend military operations in Virginia. Clinton had learned that a sizable French fleet was sailing up from the West Indies, and he feared that New York City (where Clinton himself was located with 10,000 men) was its target. Cornwallis, therefore, was to go on the defensive, march to the nearest deep-water port – Clinton recommended Portsmouth or Yorktown – fortify it, and wait there for further orders. Cornwallis was deeply frustrated by these instructions, as he believed that it was in Virginia where the war would be won. Nevertheless, he did as he was told. He marched out of Williamsburg, pausing only to lay an ambush for Lafayette's pursuing army; the resulting Battle of Green Spring (6 July) bloodied Lafayette's force but did not destroy it. Cornwallis pressed on, ultimately choosing Yorktown as his destination. By 6 August, he had landed his troops there and had begun to fortify both Yorktown and Gloucester Point, just across the York River.

Washington Marches South

As the British were ravaging Virginia, General George Washington was in the Hudson Valley in New York State, with his main Continental Army. Back in January, he had dispatched Lafayette to Virginia to deal with the traitor Benedict Arnold – and hang him if he caught him – but the continual presence of Clinton's army in New York City prevented Washington from going south himself, lest he leave the vital Hudson River undefended. But he knew that he would have to act soon. Congress was critically low on money and had not been able to supply the Continental Army nor pay its soldiers; as a result, two regiments had mutinied earlier that year. Both mutinies had been suppressed, but Washington knew that if the war was not over soon, discontent would continue to fester. Even worse tidings came from France, the United States' most important ally. The war was putting a heavy strain on the French treasury, and there were indications that France might soon try to negotiate a hasty peace, one that would certainly prove less than favorable to the United States' interests.

In May 1781, with these and other factors weighing heavily on his mind, Washington went to Wethersfield, Connecticut, to confer with Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, whose French army had recently put ashore in Rhode Island. Washington suggested a combined Franco-American assault on New York City, an idea that Rochambeau assented to. The allied forces were only just beginning to probe the British defenses when, on 14 August, Washington received news that changed everything: 29 French warships under François Joseph, Comte de Grasse, had sailed up from the West Indies and were preparing to enter the Chesapeake Bay. Recognizing this as an opportunity to destroy British power in the South once and for all, Washington abandoned his plans to attack Manhattan and sent a letter to Lafayette, ordering him to keep Cornwallis confined in Virginia at all costs. On 19 August, Washington left half his army behind to guard the Hudson Highlands and marched south with the rest of his strength, which included 3,000 American and 4,000 French soldiers.

As he neared New York City, Washington split his army up into three parallel columns, having them march at varied intervals; at the same time, he sent some men to New Jersey to begin setting up a camp, as if they were preparing to attack Staten Island. General Clinton, confused as to Washington's intentions, remained on the defensive, and did not bother to harass the Franco-American army as it passed by. A lack of horses meant that the army moved slowly, but it made progress nonetheless; on 30 August, it was in Princeton, NJ, and three days later was passing through the capital of Philadelphia. On 14 September, after nearly a month on the road, the army reached Williamsburg, Virginia, ending what became known as Washington's 'celebrated march'.

Laying Siege

Admiral de Grasse had reached the Virginia Capes on 26 August, and quickly began putting his men ashore; de Grasse had brought 3,000 French troops from the West Indies, which were now added to Lafayette's steadily growing army of 7,000. De Grasse was still anchored close by when, on the morning of 5 September, 19 British ships of the line appeared at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, under the command of Admiral Sir Thomas Graves. The French sailed out to meet them, resulting in a two-hour naval engagement called the Battle of the Chesapeake during which the British ships were badly damaged. After the battle, Graves' battered fleet continued to linger off the Virginia coast until de Grasse was reinforced by fresh ships on 10 September, compelling the British vessels to sail back to New York for repairs. The French remained in control of the Chesapeake, dashing all hope that Cornwallis might be resupplied or evacuated by sea.

Even as the sound of ships' cannons thundered across the Chesapeake, Cornwallis was desperately preparing for the siege he knew was coming. Yorktown sat on a low plateau overlooking the York River, with marshes to both the northwest and south. The British had been hard at work building two lines of defense; the outer line consisted of three redoubts on a pine tree-covered rise called Pigeon Hill along with another fort, called the Star Redoubt, in the northwest along the river's edge. The inner line of defense was only 300 yards from Yorktown itself and consisted of a series of trenches and redoubts. Work on these inner fortifications was still ongoing when, on the evening of 28 September, the first elements of Washington's army arrived and made camp outside Yorktown. Cornwallis, not wanting to spread his troops too thin, abandoned the redoubts on Pigeon Hill, and instead pulled his men back to the inner line of defense. Day and night, work on these trenches continued, both by soldiers and hundreds of runaway slaves – who had come to Yorktown hoping the British would give them freedom – while the British sunk large ships in the York River to hinder a Franco-American amphibious landing.

After this flurry of activity, the British did nothing for much of the next two weeks, a move that perplexed Washington, who referred to Cornwallis' conduct as "passive beyond conception" (Middlekauff, 586). The allies would show no such passivity. Artillery pieces were floated up the James River, unloaded, and hauled all the way to Yorktown, as allied troops occupied the abandoned redoubts on Pigeon Hill. From here, American sappers quickly began digging trenches toward the enemy lines. Earnest fighting began on 30 September when French troops assaulted the Star Redoubt – the only part of the outer line that Cornwallis had not abandoned – and were repulsed. On 3 October, Tarleton's Legion was out foraging when it ran into Lauzun's Legion at Gloucester Point; Tarleton was wounded in the action, and 50 of his men were killed or wounded.

Cannonades

On 6 October, the trenches dug by the American sappers were long enough for the allies to open their first parallel. Amidst stormy nighttime darkness, the Americans dug the trench out with shovels and pickaxes, eventually constructing a 4,000-foot-long trench anchored by redoubts at each end, that lay only 600 yards from the British line. The British met this threat with an ineffectual cannonade that was answered on 9 October, when all the Franco-American guns were in place. The French cannons opened fire at 3 p.m., and the American guns followed suit two hours later, with Washington himself firing off the first American cannon. The allied bombardment lasted all night. By the next morning, all the cannons on the British left had been knocked out of commission.

Under the protection of their artillery fire, the Franco-Americans began construction on their second parallel on 11 October, as the cannons kept up their incessant fire. British soldiers were reduced to keeping low within their trenches, while terrified civilians ran to makeshift shelters on the riverside. Even Lord Cornwallis was forced to shelter in an underground cave for a time. One British officer would later recall that the artillery bombardment made it seem "as though the heavens should split", while the streets soon became littered with corpses "whose heads, arms, and legs had been shot off" (Chernow, 162). The situation was made more dire by the fact that the only food available to the British were rations of "putrid meat and wormy biscuits" (Middlekauff, 589). Consumption of this food only led to sickness that quickly spread throughout the defending army; the British were eventually forced to slaughter hundreds of their horses for lack of food to give them. For Cornwallis and his men, the prospect of victory was growing ever smaller.

Assault on the Redoubts

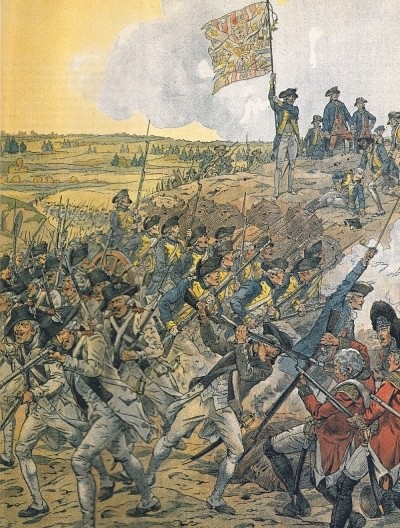

On 14 October, the allies completed their second parallel, less than 300 yards away from the British line. That same night, they launched two simultaneous assaults on the nearest British redoubts, dubbed No. 9 and No. 10; the French were to strike at No. 9, while the Americans assaulted No. 10. Shortly after nightfall, with bayonets fixed, the allied soldiers quietly ran across the quarter mile of no man's land as bursts of artillery fire colored an otherwise dark sky. 400 French soldiers under Count Deux-Ponts had nearly made it to Redoubt No. 9, when a Hessian sentry called out, demanding that they identify themselves; their cover blown, the French surged forward, but were met with a hail of musket fire from the 120 British and German defenders. The assault was slowed by the redoubt's strong abatis, and the French took heavy casualties. Once they finally broke through, however, they swiftly captured the redoubt.

At the exact same time, Colonel Alexander Hamilton led 400 American soldiers toward Redoubt No. 10, which was defended by only 77 British and German soldiers. This garrison did not realize anything was amiss until the Americans were practically on top of them. With a great war cry, the Americans crashed through the abatis – which was much weaker than the one the French had faced at Redoubt No. 9 – and stormed into the redoubt. Within ten minutes, the garrison had surrendered, and Redoubt No. 10 had fallen. The capture of these redoubts gave the allies an excellent platform from which they could storm the final British trenches before sweeping on into Yorktown itself. For the British, time was indeed running out.

The next morning, on 15 October, Washington moved his artillery into the redoubts, only intensifying the effect of the allied cannonade at such a close range. That night, it was the British who launched a surprise attack. British Colonel Robert Abercromby and 350 men crept toward the allied lines beneath the cover of darkness; Abercromby led the charge into the trenches, shouting, "Push on, my brave boys, and skin the bastards!" (Boatner, 1245). The British managed to spike six guns before they were driven back by a French counterattack and forced back into Yorktown. The assault, though undoubtedly dramatic, did not have a lasting impact, as all six cannons were repaired by the next morning. Abercromby's assault was to be one of the final moments of glory for the British in the war.

Cornwallis Surrenders

By 16 October, the allied cannonade had not let up. Cornwallis realized he could not hold out much longer and began preparing to evacuate his army across the York River to Gloucester. He managed to get 1,000 soldiers across in transports when a sudden squall blew in, making it impossible to move any more men across. The British were out of options. On the morning of 17 October, a British drummer approached the French and American lines, bearing a flag of truce and a proposal for surrender. The next day was spent hammering out the terms of surrender at the Morris House; Lt. Colonel John Laurens represented the Americans, Marquis de Noailles represented the French, and Lt. Colonel Thomas Dundas and Major Alexander Ross spoke for the British.

The terms were signed shortly before noon the next day, 19 October. Cornwallis, pleading illness, did not attend the surrender ceremony and sent his second-in-command, General Charles O'Hara, to surrender in his stead. O'Hara initially tried to offer his sword to Rochambeau, but the French general shook his head and motioned to Washington; when O'Hara approached Washington, the Virginian similarly motioned to his own second-in-command, Major General Benjamin Lincoln, who accepted O'Hara's sword. Then, the British soldiers marched out of Yorktown. They had been denied the honors of war but still looked resplendent in their new uniforms, issued only hours earlier. As they passed between the victorious American and French armies, some British troops wept while others were clearly drunk; some soldiers recklessly threw down their muskets, intending to smash them rather than see them fall into enemy hands. According to legend, as the defeated soldiers marched solemnly out of Yorktown, the British military bands fittingly struck up a tune called 'The World Turned Upside Down.'

During the entire siege, around 400 French and American soldiers were killed or wounded, while British and German casualties numbered around 600 killed and wounded, and approximately 7,600 surrendered. Cornwallis and his officers, who had been invited to dine with the American and French officers on the night of the surrender, were eventually paroled, and many British officers remarked on the civility shown to them. Although it was immediately clear that the Siege of Yorktown had been an important American victory, it did not necessarily signal an end to the fighting; Clinton was still in New York City with his army, and the British maintained strong military presences in Charleston, Canada, and in the West Indies, bases from which they could have launched new offensives. But war-weariness was already rising in Parliament, and the defeat at Yorktown proved to be the final straw. In early 1782, Prime Minister Lord North and his cabinet resigned after the House of Commons passed a no-confidence motion, and the new cabinet began peace negotiations that ultimately resulted in the Treaty of Paris of 1783, ending the war. Although minor skirmishes still took place, the Siege of Yorktown was the last significant battle of the war, cementing its legacy as one of the most important battles in US history.