The Danish conquest of England was not a singular event, but a series of large Viking invasions of England between 1013 and 1016, which eventually overthrew the native English dynasty. As a result, four kings from the House of Denmark ruled England between 1013 and 1042.

The Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard (also spelt Swein, r. 986-1014) initially conquered England in 1013, driving out the English king, Aethelred the Unready (r. 978-1013 and 1014-1016). Upon Sweyn's death in 1014, though, Aethelred returned with a show of force and temporarily reversed the Danish conquest. Sweyn's son, Cnut the Great (r. 1016-1035), fought against Aethelred and his successor, Edmund Ironside (r. 1016), from 1014-1016. After decisively defeating Edmund at the Battle of Assandun on 18 October 1016 – and Edmund's death a few weeks later – Cnut became England's second Danish king. At the height of his power in the late 1020s, Cnut ruled England, Denmark, and Norway and was heavily involved in wider European politics.

After Cnut's death, his sons, Harold Harefoot (r. 1035-1040) and Harthacnut (r. 1040-1042) ruled in England for seven more years. The dynasty reached a dead end upon Harthacnut's death in 1042, and Aethelred's line was restored to power under Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066). However, the Danish conquest continued to affect English politics after Harthacnut's death, as Scandinavian claimants threatened the kingdom during and after the events of the Norman conquest of England.

The Vikings: No Strangers to Britain

Although Vikings are most prominently associated with Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, Norse influence stretched across northern Europe and into North America by the time of the Danish conquest. After the legendary settlement of Iceland, the Vikings in Iceland established settlements, Viking Age Greenland was thriving, and Vinland (Newfoundland) was explored by the Vikings by the early 11th century. Dublin was controlled by the Vikings in Ireland, and Strathclyde and the Isle of Man were also Scandinavian-influenced areas.

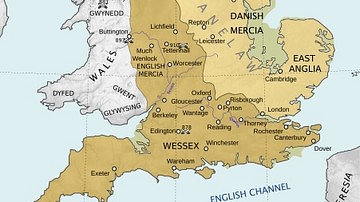

Much like the rest of northern Europe, the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had dealt with Viking raids in Britain since the end of the 8th century. A particularly fierce struggle took place during the reign of the West Saxon king Alfred the Great in the late 9th century, while the northern kingdom of York was frequently under Norse rule. Only in the 10th century did something resembling 'England' emerge as one entity, and its mid-10th-century kings frequently saw their kingdom break apart at the hands of rulers from Ireland and Scandinavia. A lull in Viking activity in England in the 960s and 970s allowed the kingdom some time to stabilize. In the 980s, small raids began again in England, but it is unlikely that these minor incursions were from Scandinavia itself or had any connection with the Danish conquest that would follow decades later.

The Major Danish Invasions

The first invasions of the Second Viking Age that certainly originated from Denmark were some of the largest of the era. Danish warlord Olaf Tryggvason (Olaf I of Norway, r. 995-1000) led a massive fleet to England in 991 and defeated local English forces at the Battle of Maldon. Sweyn Forkbeard, king of Denmark, joined Olaf for another large invasion in 994, and some historians think he may have been with Olaf's fleet of 991, as well. After failing to halt the invasions by military means, the English king Aethelred II paid tribute to them in 991 and 994, stopping them from further raiding. With Sweyn and Olaf paid off, England faced smaller Viking incursions in the late 990s and early 1000s, likely originating from neighbors closer to home. King Aethelred retaliated by raiding Strathclyde, the Isle of Man, and Normandy at the turn of the millennium.

But Sweyn returned with massive Viking armies in 1003-1005 and 1006-1007. Another Danish warlord, Thorkell the Tall, occupied much of England from 1009 to 1012 as English defenses were gradually beaten down. England saw isolated successes during this time, such as a battle led by the English lord Ulfcytel that seriously weakened Sweyn's army in 1004. An army led by King Aethelred intercepted Thorkell the Tall in 1009, perhaps containing Thorkell's movement, but neither side entered battle. Aethelred also led a successful defense of London in 1013, repelling Sweyn, but these were rare bright spots amid consistent, widespread destruction. When military resistance proved insufficient, the English paid tribute in 1002, 1007, and 1012 to give themselves time to regroup.

As the situation deteriorated throughout the late 1000s and early 1010s, England struggled to mount a united resistance. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, "...whatever was advised, it stood not a month; and at length there was not a chief that would collect an army, but each fled as he could: no shire, moreover, would stand by another" (A.D. 1010, trans. Ingram & Giles). Even the kingdom's most impressive efforts were undone by disunity: Aethelred initiated a massive shipbuilding campaign in 1009, only to see the mighty fleet tear itself apart due to infighting at court.

Sweyn's Conquest of 1013

Thorkell the Tall had switched sides after receiving his tribute payment in 1012, now fighting for Aethelred, but Sweyn returned with another invading force in 1013. Sweyn and his army secured the submission from the magnates in northern England first, gradually working his way south, accumulating support along the way. None of the English leaders wished to continue the fight against Sweyn, and even his march through the West Saxon heartland went unopposed. The only ones who resisted Sweyn in 1013 were Aethelred and Thorkell, but by the end of the year, they too seemed to have acknowledged that the situation was unsalvageable. Aethelred sent his family into exile in Normandy and followed them a few weeks later.

With Aethelred in Normandy, one of the major players in the war was gone, and Sweyn is acknowledged by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as "full king" of England in 1013. A Danish king was now the ruler of England. Sweyn also had his son Cnut with him during his 1013 campaigns and arranged for Cnut to marry Aelfgifu of Northampton, an important noble whose family had been at odds with Aethelred since 1006. With his son married to an influential English noble, Sweyn was in a strong position to pass along the throne to a new generation.

A Conquest Undone – Aethelred Strikes Back

Sweyn's succession planning became relevant almost immediately, as he died suddenly in February 1014. The Viking fleet unsurprisingly proclaimed Cnut as the next king, but Cnut's marriage to Aelfgifu of Northampton was not influential enough to secure everyone's allegiance. Some of the English nobles decided they would rather have Aethelred back. They sent word to Aethelred that they wanted to restore him to the throne, as long as he promised to be a gentler ruler and forgive everything they had done against him.

The restored Aethelred amassed an army and led it in person to Cnut's base in Lindsey. Aethelred wiped out much of Cnut's support – his army "plundered and burned, and slew all the men that they could reach", says the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – but Cnut himself managed to escape. Aethelred had the support of Norwegian warlord Olaf Haraldsson (Olaf II of Norway, r. 1015-1028) and possibly still Thorkell during his reconquest of 1014, and Scandinavian sagas credit Aethelred with two more victories during his comeback. Sweyn's conquest was falling apart as quickly as it had begun.

The next year, Aethelred took revenge on those he suspected of disloyalty, having two northern magnates assassinated at an assembly in Oxford. Aethelred had succeeded in ousting his Viking opponent, but he was also acting ruthlessly toward those he was supposed to have forgiven.

Cnut's Conquest of 1016

Following Aethelred's violent court purge of 1015, his son Edmund rebelled. Aethelred himself fell seriously ill at this time, leaving England divided and vulnerable to attack. Cnut arrived with a new army and began raiding again. Soon he also attracted the support of Eadric Streona, the powerful but fickle ealdorman of Mercia, and they raided up and down the country. Edmund amassed an army of his own but did not confront them directly at first.

By early 1016, Cnut and Eadric had the upper hand, and Edmund decided to reconcile with his ailing father. Now united again, Edmund and Aethelred met up in the field, with Aethelred leading an army from London, but the old king learned he was in danger of betrayal. He went back to London and died soon after, leaving Edmund as England's principal defender.

Edmund was proclaimed king in opposition to Cnut and began facing his enemies head-on. He directly confronted Cnut in a series of battles – Penselwood, Sherston, Brentford, and Otford – that are portrayed as English victories or stalemates depending on the source. Either way, Edmund was leading vigorous campaigns that sometimes put Cnut on the run. The momentum seemed to be with Edmund.

Edmund fought Cnut again in a massive battle known as Assandun on 18 October 1016. The danger of fighting a pitched battle with two large armies was that one side could be totally wiped out if things went poorly. In 1014, Aethelred had led an unusually large army against Cnut and succeeded, and Edmund was likely trying to do the same at Assandun. But Cnut was victorious this time, and Edmund's army was almost totally annihilated. Like Cnut in 1014, though, Edmund survived the battle. However, there was not much English support left. Many nobles and prominent churchmen had died at Assandun, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says "all the nobility of the English nation was there undone." Edmund decided to come to terms with Cnut shortly thereafter, only for Edmund himself to die before the end of the year.

The Reign of Cnut

With Aethelred and Edmund dead, Cnut finally became England's undisputed king. He shored up his new regime by marrying Emma of Normandy, Aethelred's widow, in spite of Cnut's existing marriage to Aelfgifu of Northampton. Emma helped link Cnut to the old dynasty, but several other prominent figures from the old guard were executed as Cnut rose to power. Uhtred the Bold, Eadric Streona, and Aethelred's son Eadwig were among the most notable. In their place, Cnut installed a new group of Scandinavians and Englishmen: Thorkell the Tall was made earl of East Anglia. Erik Hakonsson of Norway replaced Uhtred in Northumbria. A young English lord, Godwin, rose to prominence in the south.

As Cnut replaced much of his court in England, his brother Harald died in Denmark without children in 1018. Cnut became Denmark's king as well and would spend the 1020s splitting his time between the two kingdoms and trying out different regents for each. In 1026, Cnut fought a battle against a coalition of his Scandinavian rivals at a place known as Holy River, and Cnut added Norway to his collection of kingdoms in 1028. By 1030, Cnut's network of realms was ruled by his closest allies. Godwin became the most prominent earl in England. Cnut's first wife, Aelfgifu of Northampton, ruled Norway alongside her older son, Sweyn. Denmark was ruled by young Harthacnut, Cnut's only son with Emma of Normandy. Cnut traveled extensively among his three kingdoms, and he also traveled to Rome in 1027 to attend the coronation of Conrad II, Holy Roman Emperor and negotiate with Pope John XIX. Previous English kings had made pilgrimages to Rome and maintained diplomatic connections with the papacy, but Cnut's involvement was on a level not seen during his predecessors.

Harold I & Harthacnut

However, Cnut's North Sea Empire was already crumbling when he died in late 1035. His first wife Aelfgifu had just been overthrown in Norway. To make matters worse, her son Sweyn – Cnut's oldest child – also died around 1035. Cnut's youngest son Harthacnut was already in place as king of Denmark, but England fell into a messy succession dispute over whether Harthacnut should rule England as well. The alternative was Aelfgifu of Northampton's surviving son with Cnut, Harold Harefoot, who was older than Harthacnut and was English on his mother's side. Harold was popular in the central and northern parts of England, but he was vehemently opposed by his stepmother, Emma of Normandy. She held out for Harthacnut in Wessex, supported by Godwin. Notably, Emma's sons with Aethelred were not seriously considered at this time, meaning that Cnut had achieved something notable: only a couple decades into Danish rule, Cnut had ensured that his successor in England would be one of his children, not someone from the old dynasty.

Harthacnut did not arrive to stake his claim to England, and Harold Harefoot was consecrated in 1037. The reign of Harold I is poorly recorded, but it is known that he exiled Emma of Normandy, who had been spreading rumors that he was not actually Cnut's son. Harold's regime also fended off minor attacks from Aethelred's exiled children, Edward the Confessor and Alfred, the latter of whom died in England after being caught and blinded by forces loyal to Harold.

King Harold died in 1040, probably in his mid-twenties. Although Harold had a young son, Harthacnut was an adult with a Danish fleet at his disposal. Harthacnut was finally able to claim the English throne for himself, temporarily uniting England and Denmark again. But Harthacnut's reign was short and turbulent, and medieval chroniclers remembered him as a brutal ruler whose tenure was marred by high taxes and revolt. Harthacnut also alienated the ruling class by ordering the gruesome disinterment of Harold, mutilating the body and tossing it into the Thames.

Sick and unpopular, Harthacnut invited his half-brother Edward the Confessor to join him as co-king. Harthacnut died in 1042, still in his early twenties, returning Aethelred's dynasty to power until 1066 in the form of Edward.

Legacy of the Danish Conquest

After Harthacnut's death, the Danish line reached its end in England. Harthacnut had no known children. Aelfwine, the young son of Harold I, was recorded as an abbot in southern France twenty years later, meaning that the direct line fizzled out with the death of an otherwise obscure churchman sometime after 1062.

That did not stop Scandinavians from asserting their rights to the English throne, though. The Norwegian king Harald Hardrada felt he had a claim through an agreement Harthacnut had made with Magnus of Norway decades earlier. Harald Hardrada died in battle in England during the chaotic events of 1066, and Sweyn II Estridsson of Denmark, grandson of Sweyn Forkbeard, invaded England in 1069. Cnut IV of Denmark made plans for another invasion as late as 1085, although nothing came of it. That said, as the Norman dynasty solidified its position, the House of Denmark became predecessors of predecessors and gradually faded from memory in England.