The Hamilton-Burr duel was fought between Alexander Hamilton and his political rival Aaron Burr at 7 a.m. on 11 July 1804, in Weehawken, New Jersey. It resulted in the death of Hamilton, who received a mortal wound to the abdomen, and the end of Burr's career. The duel remains an iconic episode in the early history of the United States.

Background: The Rivalry

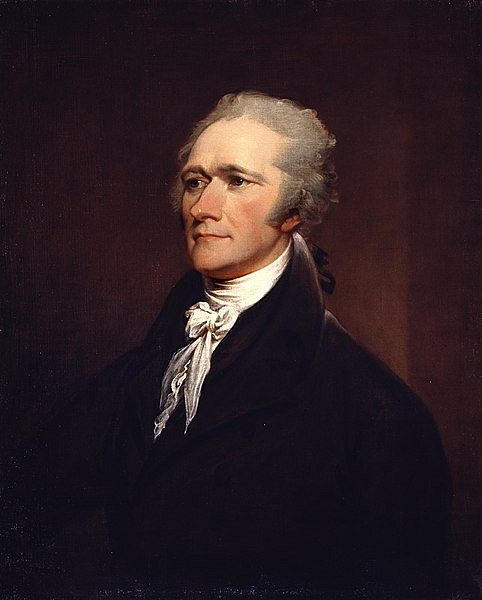

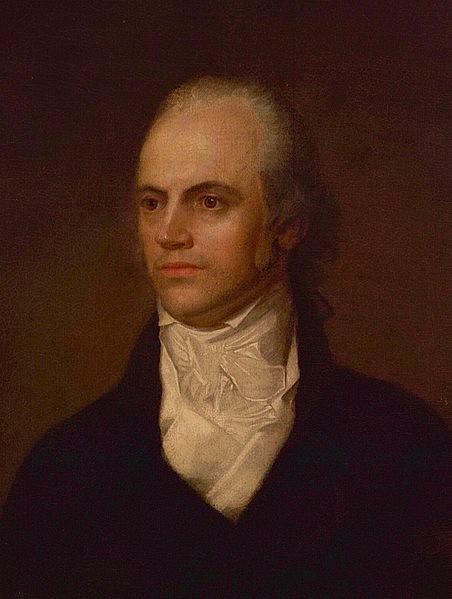

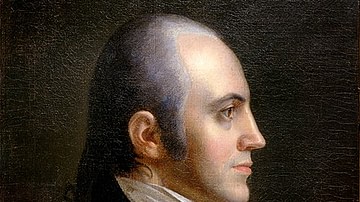

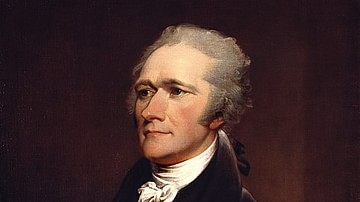

For a long while, the lives and careers of Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr seemed to run parallel with one another. Both were born in the mid-1750s and were orphaned before reaching adolescence. Both served in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, and both went on to establish law practices in New York City at the end of the war. Hamilton and Burr were both exemplary lawyers; one contemporary remarked on their differences in oratorial style, writing that "Burr was terse and convincing, while Hamilton was flowing and rapturous" (Chernow, 193). Both men were insatiably ambitious, dressed in fine clothes, and reveled in the company of women. By the early 1780s, both men were married – Hamilton to Elizabeth Schuyler, the pretty young daughter of an influential New York politician, and Burr to the widowed Theodosia Prevost, ten years his senior.

The two men had certainly known each other for some time when, in 1791, Burr decided to run for a seat in the US Senate. His opponent was General Philip Schuyler, the incumbent and Hamilton's father-in-law. Although Schuyler was one of the most influential men in New York, Burr was backed by the equally influential Clinton and Livingston political dynasties, and, in the end, Burr won the election. Hamilton, who was currently serving as secretary of the Treasury in the Washington Administration, was frustrated by Burr's victory. He was angry not only because of his familial connections to Schuyler but also because he had been counting on his father-in-law's support to help push his ambitious financial program through the Senate. The political rivalry between Hamilton and Burr is often traced back to this moment and, over the course of the next thirteen years, would only worsen.

A main point of contention between the two men was their differing views on politics. Hamilton was an idealist – as the leader of the nationalistic Federalist Party, he dreamed of turning the infant United States into a modernized power on the same level as the great empires of Europe. To this end, he focused on an agenda concerned with strengthening the authority of the central government, fostering business and industry, and building up the military. Burr, on the other hand, was no idealist. He did not see politics as a means to an end, but rather as a tool to gain money and influence for himself, his family, and his friends. Politics, Burr once said, were nothing more than "fun and honor and profit" (Wood, 280). So, although he was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party – the political faction that rivaled Hamilton's Federalists – Burr was inclined to be swayed toward whichever side benefited him the most, as would happen when he began favoring Federalist policies after his fallout with Thomas Jefferson.

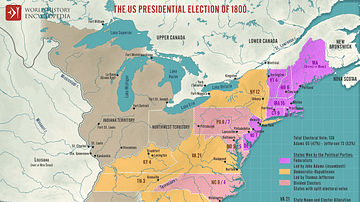

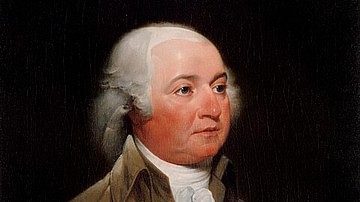

Because of Burr's apparent lack of convictions, Hamilton regarded him as a dangerous man who must be kept away from office at all costs. During the US presidential election of 1800, Burr and Jefferson received an equal number of electoral votes, and it was left to the Federalist-dominated House of Representatives to break the tie and choose which of the two men would be the next president. Initially, many Federalists sought to deny Jefferson the presidency – after all, he was the leader of the Democratic-Republicans and their chief rival. Hamilton loathed Jefferson as well, but he was much more concerned about a potential Burr presidency. He knew that Jefferson, at least, would stick to his principles, while Burr was "daring enough to attempt anything – wicked enough to scruple nothing" (Wood, 284).

Hamilton therefore used his considerable influence within the Federalist Party to sway the vote, securing the presidency for Jefferson. According to the election rules in place at the time, Burr, as the runner-up, became vice president, but he was distrusted by Jefferson, who pushed him out of his inner circle and denied him much influence in his administration. Realizing he would not be on the ticket when Jefferson ran for re-election in 1804, Burr was left to explore other options. Eventually, he decided to run for governor of New York, where he still enjoyed considerable influence.

The Challenge

The chain reaction that would lead to the end of Hamilton's life began at a dinner table. In March 1804, the former treasury secretary was dining at the home of Judge John Tayler in Albany, New York. Several other guests were present including Judge James Kent, a prominent New York Federalist, and Dr. Charles D. Cooper, a Democratic-Republican, who was married to Tayler's daughter. At some point in the evening, the conversation turned to the ongoing New York gubernatorial election, with both Hamilton and Judge Kent bluntly expressing their disdain for Burr. Dr. Cooper found himself captivated by Hamilton's impassioned, yet eloquent, words against Burr and felt compelled to write an account of the dinner in a letter to a friend. In it, Cooper asserted that Hamilton had referred to Burr "as a dangerous man and one who ought not be trusted" (Chernow, 680).

Before long, Cooper's letter had found its way into publication in the New York Evening Post. This caused a minor backlash, as Hamilton had previously promised not to influence the gubernatorial election. When Philip Schuyler wrote a letter doubting that his son-in-law had made such remarks, Cooper felt as though his integrity had been questioned, leading him to write a second letter, which was published in the Albany Register on 24 April. He reiterated everything he had said in his first letter but added that he had held some things back: "For really, sir, I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr" (Chernow, 681). The election, meanwhile, occurred that same month and resulted in Burr's defeat to Morgan Lewis. The loss left Burr in a prickly, vindictive mood that boiled over into a rage on 18 June, when a copy of Cooper's letter reached his desk.

That afternoon, Burr summoned his friend William P. Van Ness to his home of Richmond Hill overlooking the Hudson River. He sent Van Ness to Hamilton's law offices with a letter, demanding an explanation of the 'despicable' opinion alluded to in Cooper's letter, as well as a "general disavowal of any intention on the part of General Hamilton in his various conversations to convey impressions derogatory to the honor of M. Burr" (Wood, 384). The wording was vague and could apply to anything Hamilton might have said in all of their 13 years of rivalry. Hamilton said as much in his reply, telling Van Ness that if Burr cared to "refer to any particular expressions" then he would either reaffirm or disavow them (Chernow, 685). When Van Ness told him that this response was inadequate, Hamilton promised to read the Cooper letter – which he had not yet had a chance to peruse – before making a more complete response.

This response, when it came on 20 June, did nothing to mollify Burr's fury. In it, Hamilton reiterated that he had no idea which remarks Cooper had been referring to when he wrote of a 'despicable opinion', and that he could therefore not retract or reaffirm anything. But rather than seek reconciliation, Hamilton conveyed irritation that Burr would even bring the matter up at all:

I deem it inadmissible on principle to consent to be interrogated as to the justness of the inferences which may be drawn by others from whatever I may have said of a political opponent in the course of a fifteen-years competition.

(Chernow, 686)

Once again, he said that he was ready to avow or disavow any specific remarks Burr cared to bring forward. But, lacking any such particularities, he would do no such thing. "I trust on more reflection you will see the matter in the same light as me," he concluded. "If not, I can only regret the circumstance and must abide the consequence" (ibid). This response only frustrated Burr, who replied the next day:

The question is not whether [Cooper] has understood the meaning of the word [despicable] or has used it according to syntax and with grammatic accuracy…but whether you have authorized this application either directly or by uttering expressions or opinions derogatory to my honor…your letter has furnished me with new reasons for requiring a definite reply.

(ibid)

On 22 June, Van Ness delivered this letter to Hamilton, who again dismissed it and refused to disavow anything. He did not issue another response until 25 June, when his friend Judge Nathaniel Pendleton arrived at Burr's home with a letter, in which Hamilton referred to Burr's conduct as "indecorous and improper" and accused him of making compromise impossible. As biographer Ron Chernow observes, "it clearly bothered [Hamilton] that he was being asked to make amends to Burr, whom he regarded as his intellectual, political, and ethical inferior" (687). It was now clear that neither side was willing to back down, and on 27 June, Burr formally demanded satisfaction with a duel.

Preparations

Now that a formal challenge had been issued, all direct communication between Hamilton and Burr ceased and was carried out only through their seconds – Pendleton for Hamilton, and Van Ness for Burr. Duels often took place a day or two after the initial challenge to avoid word leaking out to the authorities; but, since Hamilton still had to finish up some lawsuits he was working on, the duel was set for the relatively far-off date of 11 July. Since dueling was illegal in New York State, the seconds agreed that the parties would meet at the popular dueling site of Weehawken, New Jersey; while New Jersey had also outlawed the practice of dueling, punishment was much less severe than it was in New York. Incidentally, this location was a short distance away from the spot where Hamilton's eldest son, Philip, had been killed in a similar duel only three years before.

Philip's death likely weighed heavily on Hamilton's mind in the days leading up to his own duel. Although he opposed duels on both moral and religious grounds and feared the possibility of abandoning his family and creditors by dying, Hamilton had always been aggressive in defending his honor, and felt he could not possibly refuse Burr's challenge. Hamilton was warned by friends that Burr's wrath was nothing to trifle with; Burr was known to be an excellent marksman, with some colleagues fearing that he was "determined to kill" his opponent. By contrast, Hamilton had not handled a firearm since the Revolutionary War.

But Hamilton brushed off these warnings, believing that Burr would not dare kill him – by doing so, Burr would be throwing away any chance he had at reviving his political career. Working under this assumption, Hamilton considered making a delope during the duel – that is, deliberately wasting his first shot to abort the conflict while still retaining his honor. Still, Hamilton realized the possibility that he might very well be killed, and, on the morning of 9 July, went to Manhattan to draw up his will. The night before the duel, he reiterated his intention to Pendleton to waste his shot by firing in the air. When his friend urged him to reconsider, Hamilton said that the decision was "the effect of a religious scruple" and that it was "useless to say more on the subject as my purpose is definitely fixed" (Chernow, 697).

The Duel

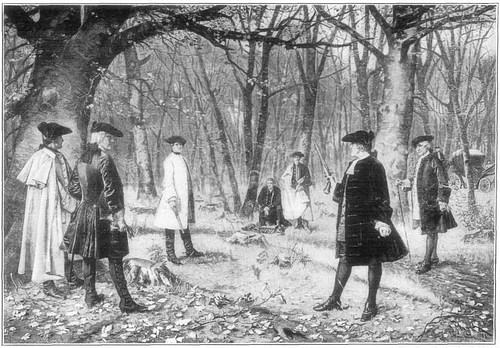

Early on the morning of 11 July 1804, Burr and Van Ness rowed across the Hudson River. They were the first to arrive at Weehawken at around 6:30 a.m. and spent the next half-hour clearing brush and debris away from the dueling ground. At 7 a.m., Hamilton and Pendleton arrived aboard a barge. As they climbed up the ledge to the secluded dueling ground, the rowers were left down below, as was the attendant surgeon Dr. David Hosack; this was to give them plausible deniability to protect them from prosecution. Pendleton and Van Ness marked out ten paces and then drew lots to determine the positions of the duelists. Pendleton won, and Hamilton chose the upper part of the ledge, facing New York City in the distance. This was an odd choice, as Chernow notes, since it would put the morning sunlight in Hamilton's face. By contrast, Burr would have much better visibility, peering into the shaded area where Hamilton stood.

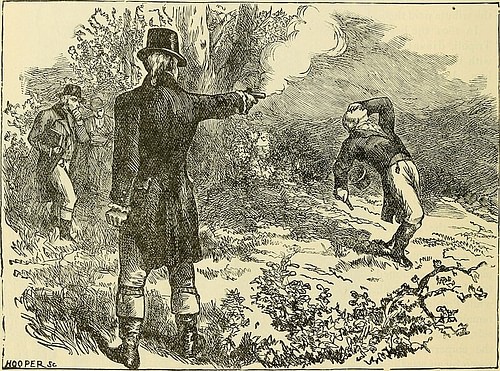

The seconds then produced the weapons, a pair of flintlock pistols chosen by Hamilton that had been used by young Philip Hamilton in his own fatal duel. The seconds loaded the pistols in full view of one another and handed them, cocked, to the principals, who assumed their places and took sideways stances, facing one another. When Pendleton asked if they were ready, Hamilton called for a pause; it was difficult for him to see in this light, he said, before pulling his glasses from his pocket and putting them on. Then, he proceeded to examine his pistol and aim it in several different directions before turning to Pendleton and apologizing for the delay. "This will do," he said, "now you may proceed" (Chernow, 702). Burr, who had no knowledge of Hamilton's stated intentions to delope, would later claim that he believed that his opponent meant to shoot to kill.

What happened next remains unclear. Certainly, both weapons were discharged. But whether Hamilton followed through with his plan to waste his shot or he aimed for Burr but simply overshot is unknown and is still questioned today. In any case, Hamilton missed, his bullet slamming into a nearby tree as Burr's shot found its target just above Hamilton's right hip. Hamilton jerked slightly to the left before falling to the ground; upon examining his own wound, he seemed to recognize that it was fatal, breathlessly telling Pendleton that "I am a dead man" (Chernow, 703). Pendleton would later recall that Burr started toward Hamilton before Van Ness held him back, reminding him that their boat was waiting; Van Ness was worried about the legal consequences of lingering too long. The two parties then crossed the Hudson in their respective boats. Hamilton was taken to the home of William Bayard, Jr. in present-day Greenwich Village, New York City. He lived long enough to say goodbye to his wife and children before dying at 2 p.m. on 12 July 1804.

Aftermath

The death of Hamilton had a major impact on early US politics. He was killed at a time when the Federalist Party was trying to make a comeback after their national defeat in the election of 1800. The Federalists would be unable to find another leader as forceful and energetic as Hamilton had been, and their movement would slowly suffocate before finally petering out in the early 1820s, ending the first round of partisan struggles in US history. The duel also had a lasting impact on Burr himself, effectively ending his political career. As Hamilton had predicted, Burr was villainized in the press and was called a 'base assassin' and 'murderer'. He was even charged with murder in both New York and New Jersey, although the charges were ultimately dropped. He laid low for a while before finally returning to Washington, D.C., to complete his term as vice president. But when his term expired, he was ostracized by both political parties. For the rest of his life, Burr refused to show remorse for the killing of Hamilton except for one moment, when he was supposed to have remarked, "had I read [Laurence] Sterne more and Voltaire less, I should have known that the world was wide enough for Hamilton and me" (Chernow, 722).