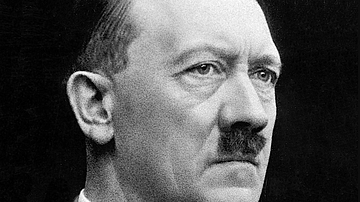

Throughout 1938, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), the leader of Nazi Germany, threatened to occupy the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. The excuse presented was that Sudeten Germans were being repressed but Hitler was intent on creating a 'Greater Germany', which included all German speakers in Europe. In the Munich Agreement of September 1938, Britain, France, and Italy agreed to recognize Germany's claim over the Sudetenland. This act of appeasement was meant to avoid a world war.

In March 1939, Hitler occupied the Bohemian and Moravian regions of Czechoslovakia, Slovakia became a German client state, and Hungary and Poland grabbed what was left of the old Czechoslovakia. When Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, Britain and France finally declared war. Czechoslovakia had been betrayed and bargained away for nothing.

Hitler's Greater Germany

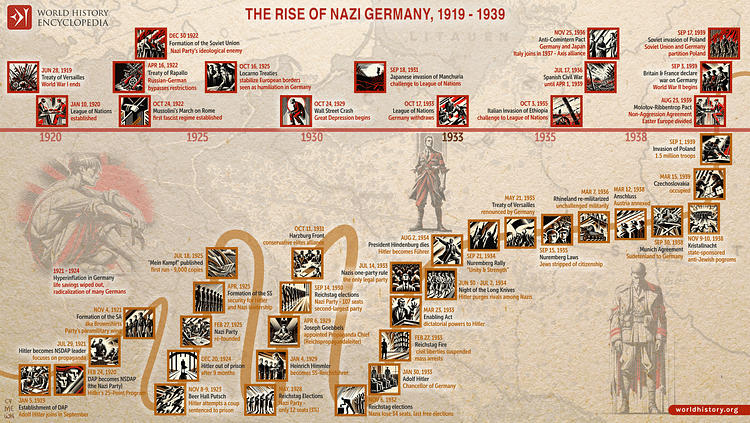

Hitler had harboured ambitions to build a German empire or 'Greater Germany' ever since his book Mein Kampf (published in 1925), in which he described the need for Lebensraum (living space) for the German people – new lands where they could prosper. Once in power from 1933, Hitler pursued an aggressive foreign policy that aimed to recover Germany's territorial losses following the Treaty of Versailles that had formally concluded the First World War (1914-18).

The first practical step towards a Greater Germany came with a plebiscite in the coal-rich Saar region, once part of western Germany but governed by the League of Nations (the forerunner of today's United Nations) since the end of WWI. In March 1935, voters decided overwhelmingly to rejoin Germany. One year later, in March 1936, German armed forces occupied the Rhineland, an industrialised area between Germany and France, which the Versailles treaty had stipulated should not have any military presence. As was the case with Japan's invasion of Chinese Manchuria in 1931 and Italy's invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, the League of Nations offered no meaningful response. Encouraged, Hitler repudiated the Treaty of Versailles and set about solidifying his alliances. In October 1936, Germany and Italy became allies with the Rome-Berlin Axis. In November 1936, Italy and Germany (and later Japan) signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, a treaty of mutual cooperation in empire-building and a united front against communism. Hitler could now concentrate on his next victim: Austria.

Hitler not only wanted more German speakers under his power but also Austria's raw materials and currency reserves; both were badly needed for the costly rearmament programme Germany was undertaking. In 1938, Hitler pressured the Austrian chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg (1897-1977) to appoint Nazi ministers in his government, but when Schuschnigg planned a plebiscite on independence for 13 March, Hitler mobilised his army, which crossed the border on 12 March. Crucially, Hitler had three factors in his favour: the support of half of the Austrian population, the Austrian army was incapable of effective resistance, and the fascist dictator of Italy Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) had promised he would not interfere. The Austrian government duly capitulated, and radio messages urged people not to resist. The Anschluss was accomplished.

The major powers, all eager to avoid another world war, reacted tamely to the Anschluss and took solace from the popularity of the takeover indicated by the plebiscites in Germany and Austria, which showed (an improbable) 99% approval for the Anschluss. Austria was absorbed into the Third Reich and became a German province. Possession of Austria gave Hitler a strong strategic position in Central Europe, a base from which he could launch further invasions, particularly in the Balkans and to his next target, Czechoslovakia. In May 1938, Hitler declared to his generals: “it is my unalterable will to smash Czechoslovakia by military action in the near future" (Dear, 597). What Hitler wanted first, though, was an excuse to take Czechoslovakia. As it turned out, he did not need it since the Western powers conspired to give Hitler the country on a plate.

The Czech Problem

Czechoslovakia was created after WWI, the region having been part of the now-broken-up Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Treaty of St Germain (1919) and the Treaty of Trianon (1920) had formed Czechoslovakia, in many ways an artificial amalgamation of several different regions. It was a democratic republic with a government headed by President Edvard Beneš (1884-1948). In 1938, Czechoslovakia contained 10 million Czechs, 3 million Slovaks, 3 million German speakers, 700,000 Hungarians, 500,000 Ukrainians, and 60,000 Poles. The government of Czechoslovakia was dominated by Czechs, which did lead to discontent from the other groups who felt their interests were not being properly represented.

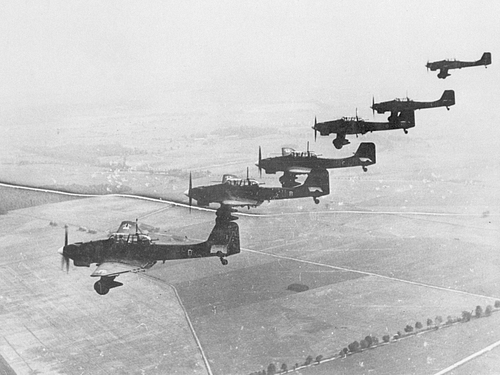

One of Czechoslovakia's greatest assets was its heavy industry, another was its defensive fortifications. As the historian W. L. Shirer notes, "Czechoslovakia developed during the years that followed its founding in 1918 into the most democratic, progressive, enlightened and prosperous state in Central Europe" (358). A significant part of the country's heavy industry and most of the German population were to be found in the Sudetenland, the western border region of the state, which was now enclosed on three sides by the Third Reich. Another great asset of the country was its well-equipped army, which was one million strong. If Hitler were to take over Czechoslovakia, what he described as an enemy aircraft carrier in Central Europe, he would have to tread carefully.

In the spring of 1938, a group of German-Czechs, represented by the Sudeten German Party (SdP) led by Konrad Henlein (1898-1945), pushed for a merger with Germany. Henlein and his party was the Czechoslovak equivalent of the German Nazi party, from whom it received both money and direction. Hitler urged Henlein to ask for concessions the Czechoslovak government could not possibly give. In Germany, the minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945) orchestrated a sustained campaign of misinformation on the theme of Germans in the Sudetenland suffering at the hands of the Czechoslovak government. The idea that Germans were a repressed minority in Czechoslovakia was a useful bit of fiction for the international press, too. The Sudetenland had never in its history been a part of Germany, now Germany was, nonetheless, calling for its “return".

Hitler had repeatedly used bluff to gain territory. Czechoslovakia was to be no different, but a certain degree of diplomacy would be required. Both the USSR and France had signed a treaty in 1935 promising to protect Czechoslovakia from outside aggression (although the USSR was only bound to act if France mobilised first). Czechoslovakia was also a member of the League of Nations, and so, if attacked, in theory, the other members were obliged to help defend it against the aggressor. Another obstacle was that the borders Czechoslovakia shared with Germany and Austria were heavily fortified. Hitler ordered his generals to prepare an invasion plan, code-named Fall Grün ('Case-Green'). Troops were moved to Germany's southern border. It looked like Hitler intended to invade, but was he again bluffing? On 12 September, at that year's Nuremberg Rally, the annual Nazi party gathering, Hitler made a virulent speech attacking the Czechoslovak government's treatment of Germans within its borders. Hitler stated: “Economically these people [the Sudeten Germans] were deliberately ruined and afterwards handed over to a slow process of extermination. The misery of the Sudeten Germans is without end" (Hite, 392).

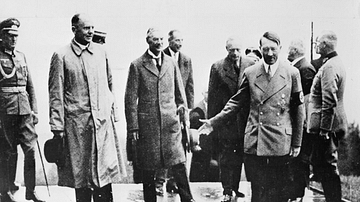

Meanwhile, Case-Green was assigned a date: 30 September. The British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940), did not know this, but he knew well enough of the German 'grievances' via Hitler's public speeches and Germany's troop movements. In August, Chamberlain sent an envoy, Lord Runciman, to hear the grievances of the Sudeten Germans. Chamberlain then visited Hitler in Bavaria in person on 15 September to try and persuade him not to take aggressive action against another neighbour. The seven-hour flight was the Prime Minister's first experience in a plane. Hitler met Chamberlain at his retreat in Berchtesgaden and suggested Germany should be given the Sudetenland if a plebiscite indicated the population's approval of such a measure. Chamberlain agreed in principle and extracted from Hitler a promise that no military action would be taken until the British Parliament had met over the issue and France had been consulted. Hitler readily agreed, all the more time to hone Case-Green to perfection.

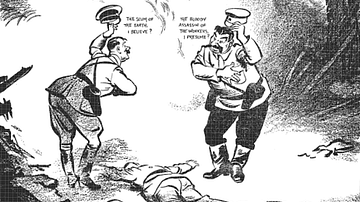

The British and French governments agreed to Hitler's demand, and the Czechoslovak government was informed of the plans, which it rejected on the grounds that it would, sooner or later, bring the entire country under Hitler's domination. Britain and France then gave the Czechoslovak government the ultimatum that if it did not hand over the Sudetenland, neither country would help what remained of Czechoslovakia in the future. As Beneš succinctly put it, “we have been basely betrayed" (Shirer, 391).

Hitler and Chamberlain met again on 22 September, this time at Godesberg on the Rhine. Hitler, sensing Chamberlain was willing to avoid a war at almost any cost, now increased his demands: Czechoslovakia must also concede territory to Poland and Hungary. What Hitler really wanted was a military occupation as such a move would restore the German army's faith in their leader. Chamberlain agreed to the new demands in principle, but the British Parliament subsequently rejected them, as did the French government. Beneš, meanwhile, mobilised the Czechoslovak army. On 26 September, Hitler made a speech in Berlin again attacking the Czechoslovak government. On 27 September, Britain mobilised its navy. War seemed inevitable and Chamberlain famously stated in a BBC radio broadcast at 8:30 p.m.:

How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing.

(McDonough, 77).

People listening in Britain were convinced that they would wake up to war the next day. Then, a miracle happened.

The Munich Agreement

Late into the night of 27 September, Hitler and Chamberlain exchanged one final correspondence in which the idea that Germany would absorb the Sudetenland but guarantee the rest of Czechoslovakia's independence was tentatively floated. A telegram was sent to Mussolini, who was eager to delay a war given Italy's poor state of rearmament, urging him to persuade Hitler to hold a conference in Munich so that the leaders of Britain, France, Germany, and Italy could have one last chance at solving the Czechoslovakia crisis through diplomacy. Hitler accepted Mussolini's proposal. The Munich Conference was held on 29 and 30 September 1938. The United States did not attend, and neither the Soviet Union nor Czechoslovakia was invited.

The Munich Agreement of September 1938, which was signed by Germany, France, Italy, and Britain, allowed Germany to absorb the Sudetenland (by 10 October), and its new expanded borders were recognised. Czechs were to leave the Sudetenland, which must not be stripped of its resources. The remainder of Czechoslovakia was given rather vague assurances for its independence and promises of (never realised) plebiscites. Two Czechoslovak diplomats were invited to Munich to hear what the Great Powers had decided to do with their country. Hitler, meanwhile, toured the Sudetenland and was received by rapturous crowds. Hitler had once again expanded his Greater Germany with the minimum of effort and no bloodshed. Hitler willingly signed a document prepared by Chamberlain, which promised that Britain and Germany would never go to war against each other.

On returning home, Chamberlain proudly declared to the British people that he had achieved “peace in our time" (McDonough, 121). Chamberlain was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1938 (perhaps fittingly given future events, he did not win it). The Munich Agreement turned out to be the final act of appeasement, a policy that allowed world leaders to convince themselves Hitler would not continue to march right across Europe. Avoiding another world war was the priority of many leaders, politicians, and the vast majority of the public in Britain and France. Appeasement, it must be said, also bought time for rearmament by all parties. There was a price to pay, though, and a heavy one. The USSR now viewed Britain and France with even more suspicion than previously. It seemed clear to the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) that the Western powers were happy for Germany to expand as long as it was in the USSR's direction. Stalin must look elsewhere for allies in a coming war. The people of Czechoslovakia felt utterly betrayed by both Britain and France. Other neighbouring states now began to nibble at a seriously weakened Czechoslovakia. In the second week of October, Poland grabbed the eastern part of the region of Teschen (Český Těšín to the Czechs, Ciesyn to the Poles). Worse was to come.

Carving Up Czechoslovakia

On 5 October 1938, the Sudetenland was absorbed into the Third Reich, and Henlein was made its Gauleiter (regional governor). Hitler personally inspected the Czechoslovak fortifications. Albert Speer (1905-1981), future armaments minister, noted:

The Czech border fortifications caused general astonishment. To the surprise of experts a test bombardment showed that our weapons would not have prevailed against them. Hitler himself went to the former frontier to inspect the arrangements and returned impressed.

(169)

Just as he had with Austria, Hitler's promise that he would respect a neighbour's sovereignty proved to be entirely false. As he noted to Speer:

I shall never again permit the Czechs to build a new defense line. What a marvelous starting position we have now. We are over the mountains and already in the valleys of Bohemia.

(ibid)

On 14 March 1939, Slovakia, led by Vojtech Tuka (1880-1946), declared itself independent, an act which was encouraged by Hitler as a means to break up the remainder of the old Czechoslovakia. On the same day, Hitler met Cezcholslovakia's new president Emil Hácha (1872-1945) to inform him that he would invade Bohemia and Moravia in the next 24 hours. On 15 March, on the pretext that they were “invited to restore order" (McDonough, 80), German soldiers marched into what remained of Czechoslovakia. Hitler, later the same day, made a triumphant tour of Prague. The United States president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, (1882-1945) described the occupation as “wanton lawlessness" (McDonough, 80). The US recalled its ambassador to Czechoslovakia, and a 25% import duty was imposed on all German goods. Britain and France froze Czechoslovakian assets in their banks. But it was all too late for Czechoslovakia.

Hungary, as promised by the First Vienna Award of 2 November 1938 (an agreement between the Axis powers), seized the southern parts of Ruthenia and a southern slice of Slovakia – both of these areas had large or majority Hungarian populations. The rest of Slovakia became a German client state under the leadership of Jozef Tiso (1887-1947). Czechoslovakia was no more.

Hitler and his allies stationed their troops in their new acquisitions and exploited them for all they were worth, extracting natural resources and using locally recruited troops in their armies. Czechoslovak factory workers were obliged to work hard or they did not receive their food ration cards. The Nazis ensured their control of the region involved the persecution of Jewish people and other 'undesirable' groups. Jewish people living in the Sudetenland were expelled to a no-man's land on the Hungarian border.

Bohemia and Moravia were given a new name, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. This new administrative area within the Third Reich was ruled over by the Nazi Baron Konstantin von Neurath (1873-1956), the former foreign minister. Von Neurath was later replaced by Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942), who was assassinated by the Czechoslovak resistance acting on orders from the British government (the Nazi reprisals for this included mass murder in the villages of Lidice and Ležáky).

The Czechoslovak political institutions that remained were now, in effect, regional bodies subordinate to Berlin. After Beneš, who had been obliged to resign, fled to the USA, Dr Emil Hácha (1892-1945) was appointed as the figurehead Czechoslovak president. The Czechoslovakian army was disbanded. Parties other than the Czechoslovak Nazi Party were banned, although there were underground resistance groups throughout the occupation. A free Czechoslovak government, recognised as such by Britain, France, and the USSR, did operate in exile and was headed by Beneš.

More territory grabs blighted the rest of 1939. In March, Germany seized Memelland, part of Lithuania since 1923. In April, Mussolini occupied Albania. In August, Germany and the USSR signed a military alliance, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (Nazi-Soviet Pact). On 31 March, Britain and France promised to guarantee Poland's borders, and in April, this was extended to Romania. Turkey and Greece also began talks of mutual protection with Britain and France. It had finally dawned on leaders in Britain and France that the fascists were intent on territorial expansion at any cost. Then, at last, the invasion of Poland in 1939 by Hitler brought a formal declaration of war from Britain and France on 3 September.

Exiles from what had been Czechoslovakia served in the armed forces of Britain and the USSR during the Second World War (1939-45). In addition, the Czechoslovak intelligence service proved itself highly useful to the Allied war effort. Back home, the Czechoslovak heavy industry (notably the Škoda armaments works) was used to boost Germany's war economy while “more than 350,000 people perished as a result of Nazi oppression" (Dear, 217).

Germany, Italy, and Japan were ultimately defeated in WWII. Czechoslovakia was reformed and Germans were expelled from the territory. Henlein committed suicide in an internment camp after his capture by the Allies. Beneš returned as president, but freedom remained elusive as, by 1948, the USSR took over Czechoslovakia, replacing one kind of dictatorship with another.