The US presidential election of 1800, referred to by Jeffersonians as the Revolution of 1800, was a turning point in the early political history of the United States. It resulted in the victory of Vice President Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party over his rival, incumbent President John Adams of the Federalist Party.

The election came at a moment of deep political polarization across the country, with each party viewing the other as an existential threat to the Constitution. At the same time, the Federalist Party was experiencing infighting, with the Hamiltonian wing of the party – the so-called 'High Federalists' – disappointed with President Adams' handling of the recent Quasi-War with France, as well as his reluctance to adhere to their agenda. When Adams dismissed two prominent High Federalists from his cabinet, Alexander Hamilton turned on him, writing a pamphlet that critiqued Adams' character and his presidency. Attacked by the Jeffersonians on one side and the Hamiltonian extremists on the other, Adams ultimately lost the election. However, in an unexpected turn of events, both Democratic-Republican candidates – Jefferson and Aaron Burr – received an equal number of electoral votes, meaning that they tied for the presidency. The tie-breaking vote was then left to the House of Representatives, which was still controlled by Federalists.

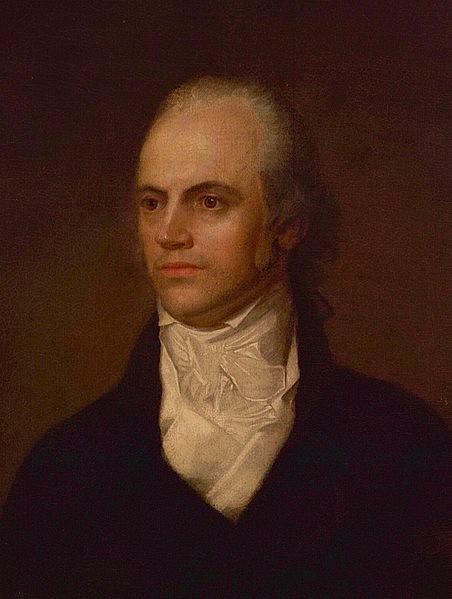

Although many Federalists initially wanted to deny the office to Jefferson, Hamilton once again interfered, using his remaining influence within the party to sway the vote towards Jefferson. Although he despised Jefferson, Hamilton feared a Burr presidency even more and was determined to prevent it. Jefferson thereby won the election and was inaugurated on 4 March 1801 as the third president of the United States. He called his election the 'Revolution of 1800' and promised to steer the country back toward the republican ideals of the American Revolution, which he claimed the Federalists had lost sight of during their time in power. It was indeed a revolution of sorts, as the Democratic-Republicans would hold on to the presidency for the next quarter century, while the Federalists would fade into irrelevance.

Background

At the dawn of the 19th century, the United States was more divided than at any other point prior to the era of the American Civil War. The Federalist Party, which had dominated the national government for the last decade, was being increasingly viewed as an aristocratic if not pro-monarchist faction that had lost touch with the principles of the American Revolution and now stood in the way of republicanism and progress. The other faction, the Democratic-Republican Party, was accused of being a group of atheistic and bloodthirsty Jacobins who sought to bring the excesses of the French Revolution to American shores. The emergence of partisan newspapers only inflamed these divisions, turning ordinary Americans against one another. Historian Gordon S. Wood writes:

As the Federalist and the Republican parties furiously attacked one another as enemies of the Constitution, party loyalties became more intense and began to override personal ties, as every aspect of American life became politicized. People who had known one another their whole lives now crossed streets to avoid confrontations. Personal differences easily spilled into violence, and fighting erupted in the state legislatures and even in the federal Congress. By 1798, public passions and partisanship and indeed public hysteria had increased to the point where armed conflict among the states and the American people seemed likely.

(209)

Each party believed that its own agenda was the best way to ensure the survival of the country and the Constitution. The Federalists were a nationalist party who, under the leadership of Alexander Hamilton, wanted to transform the United States into a modern, industrialized nation on par with the great powers of Europe. The Federalists sought to forge a strong, national government designed for the "accomplishment of great purposes" (Wood, 91). Through Hamilton's influence, Federalist policies greatly shaped the presidency of George Washington (1789-1797) – these included the Hamiltonian financial program of big banks and the funding of national debt, as well as the controversial Jay Treaty (1795), which strengthened ties with Britain. During the presidency of John Adams (1797-1801), the Federalists looked to consolidate their power by provoking and winning a war with France; although President Adams built up the military and allowed US warships to capture hostile French privateers, he did not ask for a declaration of war and, in fact, worked to de-escalate the conflict, called the Quasi-War. Adams' refusal to seek a full-scale war with France would cause a rift in the party, between him and the 'High Federalists', as those loyal to Hamilton's political agenda were known.

The Democratic-Republican Party, also known as Jeffersonian Republicans, had arisen in opposition to the Federalists. The Democratic-Republicans believed that Federalist policies were too aristocratic and too pro-British and that Federalists like Hamilton and Adams had lost sight of the principles of the Revolution, or the 'spirit of '76'. Jeffersonians believed in an expansion of republicanism and agrarianism and generally supported the French Revolution as a continuation of the American struggle against tyranny. During Adams' presidency, the Democratic-Republicans resisted the war with France and condemned the implementation of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798; this allowed for not only the deportation of non-citizens deemed hostile to the country but also the arrest of journalists and other speakers accused of spreading lies about the president or Congress. Jefferson, serving as vice president in the Adams administration, denounced the Alien and Sedition Acts as unconstitutional and condemned the Federalist administration as a "reign of witches". This was one of the larger points of contention in the upcoming election, which promised to be a rematch between Adams and Jefferson.

Partisan Attacks: Jefferson v. Adams

The campaign of 1800 picked up where the previous US presidential election of 1796 left off: with vicious attacks in partisan newspapers. The leading Federalist paper, the Gazette of the United States, accused the rival party of fostering atheism and told its readers that this election was between "GOD – AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT" or "JEFFERSON – AND NO GOD" (Meacham, 322). Reverend Timothy Dwight, the Federalist president of Yale College warned that a Jefferson presidency would lead to such calamities as "the Bible cast into a bonfire…our children either wheedled or terrified, uniting in chanting mockeries against God…we may see our wives and daughters the victims of legalized prostitution" (Encyclopedia Virginia).

On the other side, the notorious Republican propagandist James Callender accused Adams of being a warmonger and aspiring monarch, before going on to call the president a "repulsive pendant" and a "hideous hermaphroditical character which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman" (McCullough, 537). What "species of madness", asked Callender, had led the American people to elect Adams in the first place? Callender's libelous rhetoric violated the Sedition Act and earned him nine months in jail. This may have been his goal, however; the Sedition Act was widely hated by the public, and Callender was soon hailed as a martyr for free speech. The partisan papers went back and forth in such a manner, only increasing the tension throughout the young republic.

At the same time, Hamilton was looking to influence the election from behind the scenes. In his home state of New York, the Democratic-Republicans had just won control of the state legislature in the spring of 1800; since the legislature chose New York's presidential electors, this could very well cost the Federalists the national election. Hamilton and his father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, wrote to Governor John Jay of New York, asking him to change the state's election laws before the Democratic-Republican majority took office, which would overturn the state election. This was a desperate measure, Hamilton acknowledged, but it was necessary "to prevent an atheist in religion and a fanatic in politics [Jefferson] from getting possession of the helm of State" (Meacham, 327). Although Jay was a Federalist, he was not about to interfere in a fair election for partisan goals. On Hamilton's letter, he scribbled the words, "proposing a measure for party purposes, which I think it would not become me to adopt" (ibid). He did not act, and the Democratic-Republican majority was soon sworn into the New York legislature.

Federalist Infighting: Hamilton v. Adams

President Adams, meanwhile, was growing increasingly annoyed with the High Federalists in his cabinet, who had proven themselves more loyal to Hamilton than him. On the evening of 5 May 1800, Adams was consulting with Secretary of War James McHenry over the appointment of a minor federal office. McHenry had just turned to go when he said something in a tone that rubbed Adams the wrong way. All at once, years of pent-up frustration came pouring out of Adams' mouth. He accused McHenry of being Hamilton's puppet, before going on to deride Hamilton as "a man devoid of every moral principle, a bastard…a foreigner" (McCullough, 538). The president's rage continued; he charged McHenry and Secretary of State Timothy Pickering of deliberately undermining his administration and then demanded McHenry's resignation. McHenry duly resigned, and a few days later, Adams asked for Pickering's resignation as well. The secretary of state refused, retorting that he did not feel it was his duty to resign, and claiming he needed the salary to support his family. Adams was unwilling to hear excuses and fired him at once, replacing him with the more trustworthy John Marshall.

While Adams certainly had good reason to dismiss McHenry and Pickering from his cabinet, the timing was unfortunate. In McHenry's account of the discussion, he wrote that Adams was "actually insane", a charge that Democratic-Republican papers quickly picked up on (ibid). When Hamilton learned that Adams had dismissed his loyalists, he, too, flew into a rage. He embarked on a tour of New England, a bastion of Federalism, in which he encouraged Federalist electors to cast their votes for Charles Cotesworth Pinckney rather than Adams, Pinckney being a Federalist more in line with the Hamiltonian agenda. At the end of October, just before the election, Hamilton published a 54-page pamphlet entitled Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams. In it, Hamilton attacked Adams with a vitriol he had not even shown to Jefferson, condemning his "great intrinsic defects in character" and his "disgusting egotism" and presenting Adams as a man of "ungovernable temper" (McCullough, 549).

While Democratic-Republicans were ecstatic over Hamilton's letter, the Federalists balked, feeling as though their erstwhile leader had just shot them in the foot. And indeed, in many ways, he had. Federalists accused Hamilton of dividing their party and handing the presidency to Jefferson; Connecticut Federalist Noah Webster even wrote to Hamilton that "your conduct on this occasion will be discerned little short of insanity" (McCullough, 550). Hamilton shrugged off such criticisms, arguing that it was better to have someone in office like Jefferson who the Federalist Party could oppose, rather than someone like Adams who would "involve our party in the disgrace of his foolish and bad measures" (Meacham, 329).

Breaking the Tie: Jefferson v. Burr

From October to December 1800, the various state electors came together to cast their ballots. Throughout December, results began to trickle in; the Democratic-Republicans had maintained control of the South, as expected, and had won Pennsylvania and New York, earning them 73 electoral votes. Adams won in New England, New Jersey, and Delaware, giving him only 65 electoral votes. The Democratic-Republicans had clearly won the election; the deciding factor was the flip of New York's legislature from Federalist to Democratic-Republican only a few months before the election, giving the Jeffersonians the twelve electoral votes that put them over the top. Many did not fail to notice that the three-fifths clause in the Constitution – which counted enslaved people as three-fifths of a free person for the purpose of elections and taxation – had given the South additional electors, without which Adams would have won. For this reason, one Federalist paper denounced the Jeffersonians as having ridden into "the TEMPLE OF LIBERTY on the shoulders of slaves" (Encyclopedia Virginia).

But once all the votes had been tallied, a major problem was revealed. Jefferson and Aaron Burr, who had been the candidate for vice president, had tied with 73 electoral votes. According to the election protocol at the time, electors cast votes for two candidates but were not allowed to specify which candidate they wanted for president and which for vice president; thus, since every Democratic-Republican elector voted for both Jefferson and Burr, the two men ended up in a tie. Most onlookers did not think this would be an issue; surely Burr, as the more junior of the two, would graciously step aside and allow Jefferson to assume the presidency, as the voters had clearly intended. But as the days went by, and Burr continued to stay silent, it soon became apparent that he would do no such thing. As the Constitution stipulated, the tie-breaking vote would be handed off to the House of Representatives – which, to the horror of the victorious Democratic-Republicans, was still controlled by the Federalists.

Many feared that the Federalist congressmen would deny Jefferson the presidency or, even worse, that they would steal the election by using some constitutional loophole. "What will be the plans of the Federalists?" a distraught Jeffersonian, Albert Gallatin, wrote to his wife. "Will they usurp the presidential powers?...I see some danger in the fate of the election" (Meacham, 333). Governor Thomas McKean of Pennsylvania put it in more blunt terms:

If bad men will dare traitorously to destroy or embarrass our general government and the union of the states, I shall conceive it my duty to oppose them at every hazard of life and fortune; for I should deem it less inglorious to submit to foreign than domestic tyranny.

(Meacham, 336)

20,000 Pennsylvania militia were at the ready, McKean promised, and would not hesitate to arrest and "bring justice to every member of Congress" who "should have been concerned in the treason" (ibid). The prospect of civil war had never seemed more likely. On 11 February 1801, the House began its vote; after a long, roll-call vote, the House reached a deadlock, and the vote was taken a few hours later to the same effect. This continued for 35 such votes over six days. The Federalists were determined to deny the presidency to Jefferson, who they considered to be their archnemesis, and preferred to support Burr, who had apparently offered to promote crucial Federalist policies should he be elected president. The Federalists may well have ended up handing the presidency to Burr had it not been for one man: Hamilton.

Alexander Hamilton hated Jefferson just as much as any other Federalist, but he feared a potential Burr presidency more. "Jefferson is to be preferred," he wrote in a letter to James A. Bayard, a moderate Federalist congressman, "he is by far not so dangerous a man; and he has pretensions to character" (Meacham, 339). Hamilton believed that Burr had no principles, and was therefore much more dangerous to the nation's institutions; he wrote that Burr was "daring enough to attempt anything – wicked enough to scruple nothing" (Wood, 284). Bayard seems to have been convinced by Hamilton's arguments. He told his colleagues that, while he could not bring himself to vote for Jefferson, he would nevertheless withdraw his vote for Burr. While no Federalist voted for Jefferson, Bayard's decision swayed several other Federalists to abstain. So, when the 36th roll-call vote was taken on 17 February 1801, Jefferson won. The matter was decided, and the young United States had proven that a peaceful transition of power between two rival political parties was possible.

Jefferson's Inauguration

Just before dawn on Inauguration Day – 4 March 1801 – John Adams made his silent exit from the capital, heading back to his farm in Quincy, Massachusetts, to begin what would prove to be a 25-year retirement. His hurried exit does not seem to have been an intended slight toward Jefferson, but merely a way for a prideful man to maintain his dignity; he did not mean to stick around to see his enemies gloat over his defeat. Several hours later, President Jefferson stood before the unfinished Capitol Building and was sworn into office. He rejoiced in the so-called 'Revolution of 1800', as he referred to his election, and promised to guide the wayward nation back to the 'principles of '76'. However, at the same time, Jefferson promised he would seek reconciliation between the two parties, famously opening his inaugural address by proclaiming, "We are all Republicans – we are all Federalists".

Hamilton's interference in the election – in sinking the chances of John Adams, then Aaron Burr – cost him much of his influence within the Federalist Party. Whether he would have regained that influence is unknown, as he was killed three years later in a duel with Burr. In any case, the Federalists would never recover nationally from their loss in 1800. Though certain pockets of the country like New England would remain strongholds for Federalism, they would never again win the presidency. In fact, their influence would dwindle until the early 1820s, when their party would fizzle out altogether. The Democratic-Republicans, however, would maintain control of the White House for a generation. While their party would eventually splinter, causing a new round of partisan struggles, the Revolution of 1800 – and the subsequent rise of Jeffersonian Democracy – would greatly influence the development of the United States, making this election one of the most important in US history.