Yellow Hair: George Armstrong Custer is the Cheyenne and Arapaho account of Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876), his interaction with the Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle (l. c. 1803-1868), the Washita Massacre (27 November 1868), and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (24-26 June 1876). The piece is significant in presenting the Native American view of events.

The account was related to scholars Alice Marriott and Carol K. Rachlin by Mary Little Bear Inkanish, John Stands-in-the-Timber, and John Fletcher of the Cheyenne and by Richard Pratt of the Arapaho. Although the account conforms in many aspects to the narrative accepted by scholars of American history, there are significant departures in detail. The phrase "history is written by the winners" is not quite accurate. Histories are also written by the losers in wars and conquests; they just never become as widely read as the dominant narrative of the victors.

Yellow Hair: George Armstrong Custer is a prime example of this. Here, the depiction of Custer is quite different from his heroic image as a defender of freedom, and this view has increasingly gained ground in the last 100 years. Today, Custer is a controversial figure as the Native American interpretation of the man has become more widely accepted by mainstream scholarship.

Cheyenne & Arapaho and US Accounts

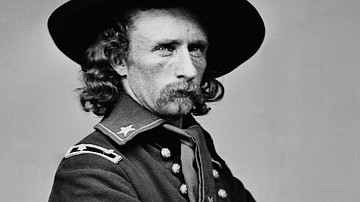

Custer was a relative newcomer to the home of the Plains Indians, only arriving in the region in 1867 toward the end of Red Cloud's War (1866-1868). He served under Major General Winfield Scott Hancock (l. 1824-1886) in the wars against the Cheyenne and Arapaho and became known as an "Indian fighter." After his death at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876, his wife, Elizabeth Bacon "Libbie" Custer (l. 1842-1933), and his supporters elevated Custer to the role of martyr for the cause of civilization and defender of the United States against the 'savagery' of the Native peoples of North America. The Native American version of Custer and the major conflicts he was involved with contradicts this narrative.

Objective review of the so-called "Indian Wars" also challenges the accepted narrative of Custer as a hero and martyr, as his actions and those of others were in breach of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which promised the Sioux their lands in perpetuity and the same for the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 had made the same promises, and before that, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 had, essentially, done the same, but none of these were honored by the US government.

In the following account, there are several details that differ from the better-known narratives. Here, it is said that Custer sent men to find Major Joel Eliot (l. 1840-1868) at the Washita Massacre when he broke from the main body of cavalry to attack the Arapaho camp, while the official report claims Custer never tried to find out where Eliot was. The failure to support Eliot is here given as the reason Custer was recalled to Washington while, in the more widely accepted narrative, it was to testify at a hearing involving monopolies and price-gouging at Western trading posts.

There are other details, some minor, in the account, but among the most interesting is the depiction of the death of the peace chief Black Kettle and his wife. According to the standard narrative, they were both killed while fleeing across the Washita River, shot in the back. Here, they are shown dying at their home, Black Kettle clutching the American flag, in a final defense of his village and way of life. The differing details of the Euro-American and Native American accounts are not only interesting in their own right, but reflect a truth regarding historical writing which, actually, can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia: what actually happened never matters as much as how what happened is remembered. Every narrative of the past - personal, communal, or national - serves a purpose in the present in defining oneself.

Text

The following text is taken from American Indian Mythology by Alice Marriott and Carol K. Rachlin, Thomas Y. Crowell, Company, 1968. Although included in an anthology of Native American myths, the account is understood as historically accurate. Among the details of the piece that are challenged are how the narrators knew what Libbie Custer was thinking the night before Custer left for battle, the specifics of the last dinner, and the description of how the divisions of General Terry's command were deployed. The Cheyenne and Arapaho account of the Washita Massacre also differs sharply from Custer's account of the Battle of Washita River.

After the treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek [1867], the Cheyenne and Arapaho, who were old allies, sat in the council tipi together. All the leading chiefs were unhappy and disturbed for, among the white men present at the signing of the treaty, had been Yellow Hair – George Armstrong Custer.

Custer was known to have a Cheyenne wife and a half-Cheyenne son. The same man who disobeyed his commanding officer's orders so that he might make a dash to Fort Riley, Kansas, to see his white wife, also spent many nights in a Cheyenne tipi. How could the chiefs trust him? He would trick women, disavow his son's parentage, and lie to his friends. He could not be trusted.

They sent a young man, as messenger, with a word that Custer should come to Black Kettle's camp and smoke with him. Black Kettle was a peace chief of the Cheyenne – an old man, loved and respected by everybody. His wife prepared a feast for the visitors, and they all sat down and ate together.

After the feast, the young messenger brought Black Kettle a pipe bag. It was of the finest fawn skin, and was beaded in horizontal red, yellow, black, and white bands. Black Kettle's wife belonged to the women's secret society, and she had the right to make that kind of beadwork.

From the bag, Black Kettle drew out a T-shaped pipe of red pipestone with a straight white dogwood stem. He fitted the stem to the pipe bowl and filled the pipe with native tobacco mixed with shredded sumac bark. Very carefully, Black Kettle lifted a coal from the tipi fire, using a pair of sticks for tongs, and lighted the pipe. When he had blown smoke to Maheo above, to mother the Earth, and to the four corners of the world, Black Kettle spoke.

"Yellow Hair," he said, "we have called you to our council because we all wish to make a peace and keep the peace. We have set our marks on paper, but that is the white man's way. Now we ask you to swear the peace in the Indian way, too. Smoke with us, Yellow Hair."

Custer tossed back the long yellow locks that lay on the shoulders of his fringed and beaded buckskin shirt. He never wore a uniform if he could help it and that was another thing the Indians did not like. If he joined the soldiers, if he gave orders to the soldiers, then he should dress like them. The yellow locks might be thinning on top, but they still hung thick from the sides and back and fell across his shoulders.

One thing every Indian knew about Custer, he never smoked. Even smelling tobacco smoke, he said, made him feel sick. But success and advancement depended on his control of these Indians, so Yellow Hair put out his hand for the pipe.

Yellow Hair followed Black Kettle's motions, and let a little smoke trickle from his mouth to each of the six directions. He did not swallow any smoke, but he put the pipe to his mouth six times and blew out six puffs of tobacco smoke. Now Custer was joined to the Cheyenne and the Arapaho in what the Indians hoped would be a lasting and safe peace. The other chiefs smoked in their turns.

"Now, Yellow Hair," Black Kettle said, "you have smoked with us and promised us peace. You may go."

Custer left the tipi, denting the ground with the heels of his boots. Black Kettle shook the dottle from the pipe into the palm of his hand and sprinkled a pinch of it in every heel print.

"Yellow Hair has gone," he said. "Hear me, my chiefs. If he breaks the promise he has made us today, he will die, and he will die a coward's death. No Indian will soil his hands with Yellow Hair's scalp."

"Hah-ho," said all the other chiefs. "So be it. If Yellow Hair breaks the promise he has sworn in the peace treaty, then let him die a woman's death."

[In 1868], Black Kettle and his band made their winter camp on the banks of the Washita River. It was a peace camp, a settled camp. There were brush windbreaks around many of the tipis, and the children played in safety. In the center of the camp stood the beautifully beaded tipi where Black Kettle and his wife lived, and to one side of them and to the other were the keepers of the Cheyenne sacred medicines.

The weather was bitterly cold, for a blue norther had swept across the plains that afternoon, and everyone shivered under its weight of hail and sleet. People huddled inside their tipis, away from the force of the wind; sat close to their fires and, after they had eaten dinner, told stories of the old days and the old ways. It was a rich camp. The women of Black Kettle's band worked hard, and they were well supplied with dried meat, fine clothes, and painted, beaded, and quill-embroidered robes.

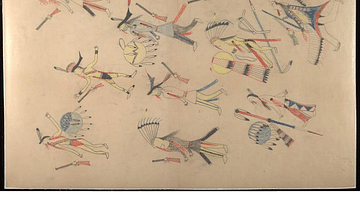

By midnight, the camp was silent, and then Yellow Hair struck. He and his troopers, with the storm at their backs, had ridden the seventy miles from Camp Supply in two days and now, in the darkness, they attacked the peace camp.

Custer had divided his forces, sending a small detachment of troopers downstream to attack a camp of visiting Arapaho. He, with the main body of troops, struck at Black Kettle's camp. The old man died in the ruins of his flaming tipi and fell with the United States flag – given him at Medicine Lodge as a token of the peace he was to keep – still clutched in his hand. Black Kettle's wife stabbed herself and fell dead across her husband's body.

Downstream, there was shooting at the Arapaho camp, and then there was no more shooting.

The troops of the Seventy Cavalry gathered together all the wealth of Black Kettle's camp and set fire to every beautiful thing those Cheyenne possessed. Even some of the soldiers cried when they saw the destruction of robes and food belonging to women and children.

By daylight, with Sharp's carbines, the troopers shot all the horses in the great herds pastured across the river.

And still there was no more shooting from downstream. Yellow Hair sent a detachment to see if the Arapaho had been wiped out like the Cheyenne. The troops found that the Arapaho and their camp were gone. On the ground were the bodies of Major Joel Eliot and his men – all scalped.

Yellow Hair had broken the peace, but his men had died like men.

Now the proud Cheyenne became, for a time, a broken people. They suffered imprisonment and death from disease and starvation. Yellow Hair reported his great victory over Black Kettle, but he also had to report that he had let men be killed without sending them support. Even "Woosinton" [Washington, D.C.] could not let that go by. They sent for Yellow Hair to go east, and they punished him by making him stay there for one whole year.

Then Yellow Hair and his white wife came back to Fort Abraham Lincoln. His Cheyenne wife had died of grief, and her sisters had taken her son and hidden him, so he could be raised as an Indian. Fort Abraham Lincoln was far away, north on the Yellowstone, so the Southern Cheyenne sat and waited and worked out a plan.

Quietly, messengers moved from tribe to tribe, up and down the plains. They went to the Arapaho, of course, and to the many different bands of Sioux. The Crow and Pawnee, who had taken the white man's uniforms and served in the army as scouts, the messengers avoided.

In time, just as quietly, the villages moved. A few camps at a time drifted into the territory of Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa Sioux chief. Here the groups spread out, along the Little Bighorn and Tongue rivers, and waited until all the men were armed and ready.

The Crow and Pawnee came into Fort Abraham Lincoln with word that the tribes were gathering. They might attack the white settlements or the fort. Trouble was on its way.

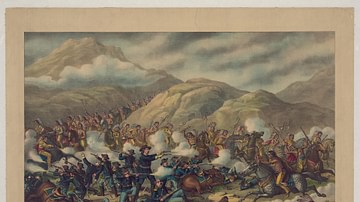

There was a council of white soldiers, and General Terry, the commanding officer at the post, gave his orders. Yellow Hair would go one way, he himself would go another, and Major Marcus Reno would go the third. They would all come together to surround the great camp on the Little Bighorn.

With Custer would ride his brother, Lieutenant Tom Custer, and Captain Myles W. Keogh. Captain Keogh was famous everywhere for his devotion to his big bay gelding, Comanche. The two talked to each other like brothers and Comanche seemed to know what the captain thought before the words had formed in the man's mind.

The night before they set out, these three men, with some other officers, gathered in Custer's quarters for a farewell dinner. Elizabeth Custer and her Negro cook, Eliza, provided a good one of venison, and roast sage hens, and any other game the men had brought in. Lat in the evening, Tom Custer, Yellow Hair, and Keogh shaved their heads with horse clippers. Elizabeth wept when she saw the fading golden locks fall to the floor; then she comforted herself with the thought that, perhaps, the Indians would be less likely to recognize and attack her husband if they did not see his long hair.

Early in the morning, the troops rode out of the fort and the women watched them go. Some women wept, and others held back their tears and bravely waved their handkerchiefs in good-bye. As the women and the post guard watched, and the band played "The Girl I Left Behind Me", and the regimental marching song, "Garry Owen", one of those miracles of the plains light appeared. Riding above the troopers were their images mirrored against the sky by a mirage. Someone cried, "They are riding to their death!" but the shout was quickly stilled.

If the Pawnee and the Crow knew what was happening in the Indian camps, the Sioux, the Cheyenne, and the Arapaho knew what was happening at Fort Abraham Lincoln. They were prepared and, when the charge came, the Indians met it like rocks.

Custer and his troops were driven back and took refuge on top of a steep hill, almost a bluff, north of the Little Bighorn. There the Indians could surround them and slowly, methodically, tear them to pieces. Major Reno was pinned downstream by the Arapaho. General Terry had not yet come up in support. Yellow Hair died as Major Eliot had died, in the center of a ring of soldiers, killed by "the finest light cavalry in the world" [a phrase attributed to General George Crook regarding the Plains Indians].

The Indian women struck camp and loaded their horses while the battle still went on. When victory came, the Indians melted away into the Black Hills. By the time General Terry relieved Major Reno, and rescued his detachment, the only being left alive on the hilltop was Captain Keogh's great horse, Comanche. The dead man's hand still clutched the reins. Those two were like brothers and no Indian would separate them. Later, General Terry took Comanche to Fort Riley, Kansas, and there he lived until he died of old age – no rider ever mounted him again, but he was led in every review on the post. Comanche's body is still preserved in the Kansas State Historical Museum.

Whether, as the Cheyenne say, no one recognized Yellow Hair with his head shaved and whether, as the Arapaho say, he was a coward and not worth scalping, we do not know. We do know that his body, unlike others on that battlefield, was not mutilated. Yellow Hair lay on his back, with a woman's knife thrust through his chest, but he was dead before that Cheyenne woman struck him, so they say.