The Woman and the Monster is a legend of the Arapaho nation about a woman who, seeming to drown in a river, is transported to the realm of an elemental water spirit who teaches her the proper way for her people to honor him and, in so doing, be safe in his waters.

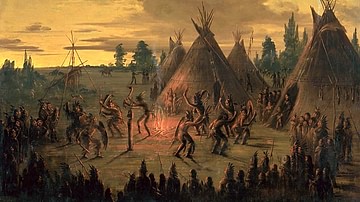

The story is thought by some scholars to be an origin tale for the prayer cloths tied to trees and bushes along springs, streams, ponds, lakes, and riverbanks, honoring not only the spirit (or spirits) of that particular body of water but also those of any of their loved ones and relatives who may have died there. It is also considered the origin myth for the ritual of self-cutting as a means of sacrifice. Although, historically, the Arapaho observed the ritual of the Sun Dance, they did not engage in the self-torture aspect of the rite as practiced by the Sioux. Instead, they would offer other sacrifices to the Great Spirit, including cutting parts of their flesh.

The Woman and the Monster also illustrates the belief, held generally by Native peoples of North America in the past and present, that the world is alive with unseen spirits who must be acknowledged and respected. Such spirits can make themselves and their desires known as it suits them but should always be understood as present and aware of people's actions. One should, therefore, always behave in private as one would in the company of others, maintaining respect for the natural world and its many inhabitants, the seen as well as the unseen, such as water spirits.

Water Spirits & Proper Respect

Elemental water spirits, according to many Native American nations, are jealous of their realm and expect proper sacrifice and respect from those who use their water, for whatever purpose. Proper acknowledgment of the spirit of place for the gift of water was, and still is, understood as most important because, to simply take without asking, would be seen as thoughtless and rude, the same as not saying "thank you" for a gift, or even as stealing.

The water spirit in this story is similar to those depicted in the stories and legends of other nations, such as the Ogopogo of the Secwepemc (Shuswap) and Syilx (Okanagan) First Nations of modern-day Canada. The Ogopogo is described as an enormous serpent with a dragon's head while, in the Arapaho tale below, the spirit takes the form of a handsome young warrior. Whatever form a spirit takes, it is understood as a member of one's family and community, requiring the same level of respect. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman comments:

Although all Native Americans recognize that nature is imbued with spiritual significance, spirits of nature vary considerably in their power and significance. In the realm where the worlds of humans and spirits intersect, the relationship between them can be complex. Some spirits are seen as vast and even universal potencies, while others may hold sway over more specific aspects of the world, essentially maintaining the world and revealing themselves in the form of natural phenomena, such as weather, wind, lakes, plants, and animals. These spirits are regarded as kin, and as such they have certain rights and obligations to each other as well as to the humans in whose proximity they live.

(82)

In Arapaho belief, all living things belong to a single family born of the Great Father (or Great Spirit, Be He Teiht) and all live together in the World House. In order to live peacefully with one's family members, one must always show proper respect, even if a request seems unreasonable, as – especially when dealing with supernatural kinfolk – one cannot hope to understand another's reason for that request but can only proceed the best one can in maintaining harmony among all who live in the World House.

The woman narrating the story clearly understands, and easily accepts, the fact she is dealing with elemental, supernatural, entities, and recognizes it is in her own best interests to comply with their requests. When the water monster tells her they will need to have intercourse if she ever wishes to see her family again or understand who he is, it is not a threat or a demand, but simply what is required from a mortal by a supernatural entity. Once a gift has been freely offered, it is reciprocated and, in this case, by the promise that the woman will never drown in any waters, nor will her people, as long as she bathes there first.

As with all the works of Native American Literature, The Woman and the Monster is open to various interpretations. The most common, however, recognizes the importance of gratitude – a significant cultural value of the Arapaho – as the female narrator is taken by the water, and should have drowned, but is saved and returned to her people by the water monster, the spirit who both is and owns the waters. In return for the gift of life, the only proper response is gratitude and humility, as the woman shows in her actions toward the end of the tale.

Text

The following text is taken from Traditions of the Arapaho by George A. Dorsey and Alfred L. Kroeber, 1903, republished by University of Nebraska Press in 1997.

The Northern Arapaho were living along the Platte River years ago. At that time the different tribes, such as the Shoshone, Crow, Sioux, —the most friendly ones, used to come around with a certain amount of skins and furs, to trade with the tribe. As the Crow Indians were good marksmen, they had quite a supply of elk skin when they came to the camp-circle, which was on the south side of the Platte River. Quite a good many Arapaho caught their big horses and packed their goods to trade with the Crow Indians. Our horses were out far in the prairie, and my boys caught the tamest, which were very small. So, I took some beads and a few other articles and got on the pony.

The Platte River was high that year, and was very dangerous, being swift. Twice I was out of elk skin, which I needed for various things. I aimed to get some that day. The other Arapaho had reached the other shore all right, and it came my turn to cross. I was not afraid at all, putting my faith in the pony; so, I rode in the river.

Just as I was in the middle of the channel the pony was swimming and I began to feel different, losing my senses all at once, because of the strange sight before me; and the pony was losing its strength every moment. All on a sudden the water took us out of sight, and I found myself standing on the dry sand. When I went into the water (drowned) I knew that I should be wet in clothes; but they were all perfectly dry."

As I looked around to see the rest of the sandbar in front of me, there stood two young men, dressed in fine Indian style. These men who appeared to me were a soft-shell turtle and a beaver. "Well, young woman, we came after you and we want you to come along," said the men. Without offering any objections, I consented to go, for I was at their mercy. So these young men started off and I followed their path, which was a dry river bed.

As we walked around the bend of the river, we came to a black painted tipi, with pictures of two water monsters, one on each side of the tipi. Both of these monsters faced the door of the tipi; in other words, the animals wound around the bottom of the tipi. One of these water monsters was red and the other a spotted, —black and white. In the front of the door, where the breastpins are used, was a sun, painted in red (being a disc). The red painted sun meant the rising sun in the morning. Back of the tipi at the top was a half-moon in green color. There was a bunch of eagle feathers tied to the tipi pole.

As I came nearer to the tipi, I heard the people inside talking to each other. "Here is the woman that you wanted to see," said the two young men. "Tell her to come in!" said somebody with a manly voice. These two young men went in, and I followed. "Welcome! welcome! Be seated!" said the rest of the young men. "Take your seat with that man in the center," said one.

I looked across the fireplace and saw a beautiful young man, painted all in red, and who was naked; at both sides there were more young men, sitting in good positions. In front of them were different kinds of medicine bags, with several small bags of medicine roots and herbs, and weeds. These men were dressed in different shades, according to their taste.

So, I took my seat on the right side of this beautiful young man. "When I saw you, I was very much charmed by your pretty looks and could not help but send two of my young men after you. Now if you want to see your folks again, I shall have to ask you for intercourse, and then I will tell you of myself, power and place, and so on, with the others here. Consider this tipi, outside and inside, and the people with all their medical properties. That man belongs to the Beaver family, and the next one is of the Otter family, and so on" (calling each one after the name of some tribe of animals). Sitting in front of the medicine bags were lizards, frogs, turtles, fishes of various kinds, snakes and other water animals. When these men turned to animals, they looked at me sharply, and all in reverent mood.

So, we had intercourse, thus saving myself to a certain extent. ''Now, my dear woman, I want you to listen to me carefully and sincerely," said this man to me. "You must bear in mind that I am the owner of rivers and live in different localities against the steep banks where water is deep. There can be more than one of my kind, but those will be at the springs and small lakes. Be sure not to eat any fish. If you are going to the river to bathe, tell your companions that unless you go and bathe first, they will be drowned. If your companions should not believe your warning, they will be drowned. Go in and take a good bath first, then they can go in the water.

"When your people wish to show some respect and reverence, have them cut off small pieces of their skins. Let them be as many as they wish and tie them in a bundle and place it on a small stick. This they must thrust close to the mouth of springs and above or on the side of the steep banks where water is deep. When they leave the place, I shall appear to such and receive their offerings and prayers, and in return I shall see that they cross the rivers in safety, and swim in the rivers and creeks with their children with no trouble. Remember this and tell it to your people when you get back.

"If your people won't do this, then there is another way in which they can show their respect. Tell them that they can tie a red flannel to a bush or tree above the spring. When the people cut their skins off in small spots on their wrists, and get them tied in small bundles, let them point the stick to the head of the river and lastly to the mouth of it, praying, saying to me, in good faith, 'My Grandfather, Last Child, I have cut seven pieces off my wrist, hear me with your tender mercies. May my life be prolonged; so with my relatives and friends; and lead me into prosperity and happiness! During the day may I gain the good will of everybody in contact with me; also, when I sleep at night, that I may be protected from injury and harm, and drink that sweet water which comes from you; that wherever I drink water, it may be clear and wholesome for my body as well as for my kindred. Have pity on me and remember me in my daily anxieties, and let my seed multiply according to your will, if it may be necessary! Hear my earnest prayer! I cannot say much, but offer the same with all good things. So it may be for me, and to all in the tribe."

This is the kind of supplication given by the husband, the monster animal. That is the reason why the people cut themselves on their wrists and tie-red flannels to the branches along the most dangerous places by the rivers. This is voluntarily done by the Indians.

After this man had told the woman of certain restrictions, she went out and found herself standing on the bank, facing toward the deep water, above a steep precipice.

I looked around and saw a big camp-circle a short distance above the river, and also there was still a visiting camp of the Crow, and some Shoshoni. The monster told me to paint myself in red when I wanted to see him again and plunge into the river; when coming out I was to be cleansed from all impurities and offer some prayer.

When I returned to the camp-circle, I found that my folks were mourning in my behalf—some had cut their hair off, cut their flesh and had gone through some tortures; but when they saw me, they were so glad to see me again alive, since they knew I was drowned. When the people asked me about my disappearance, I told them that they turned me loose.

After I had remained in camp for some time, I painted myself all over the body in red, thus living up to the way of my husband, the water monster. This tipi, which was painted all in black with symbolism—two monsters on one side, the sun in front, and at the back of the tipi the half-moon, —was a gift to me, also a lot of medical supplies; but I did not want to make a tipi like it, because, as a rule, the women are less thought of as doctors.

[Dorsey's commentary]: This monster is called by the Arapaho the Last Child. —"Hi-taw-ku-saw." The Indians are to a certain extent afraid of deep holes in rivers; the children are forbidden to bathe at such places, because the Indians occasionally saw some things (animals) or bad signs. They would offer prayers to the Last Child for this water and kind treatment. The four-footed animals stand the same chances (risks) as human persons.

Among the Northern Arapaho there is a story of an animal captured, which turned into a solid stone. The whole body (stone) was carried out away from the river, and there were many presents given to it for its good will and treatment. The presents were of eagle feathers, calico, and other valuable articles—jewelry, etc.

There were two women going after some water, and upon reaching the place, they saw the monster in the water just at the surface. It frightened the women into fits (medicine). One of them died, and those who carried her out are living yet, except one. In course of time this one disappeared, and it is thought that the animal returned to the water.