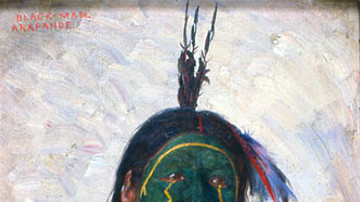

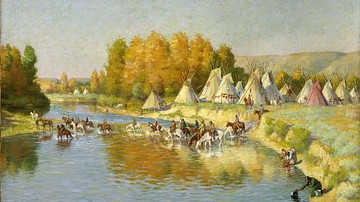

Nih'a'ca tales are Arapaho legends concerning the trickster figure Nih'a'ca, who, according to Arapaho lore, is the first haxu'xan (two-spirit), a third gender, often highly regarded by many Native American nations, including the Arapaho. The Nih'a'ca tales are similar to the Wihio tales of the Cheyenne and the Iktomi tales of the Sioux.

Circumstances and situations differ between the Nih'a'ca tales and those concerning trickster figures of other Native peoples of North America, but the central character of the trickster plays the same role – sometimes as sage and mediator, sometimes as schemer and villain – in them all. In the case of Nih'a'ca – always referred to by the male pronoun in English translations of Arapaho tales – he is frequently depicted in legend as someone who tries to better himself, usually at the expense of others or by trying to take shortcuts, and suffers for it.

At the same time, Nih'a'ca can be wise, offering advice, or clever, as in the story Nih'a'ca Pursued by the Rolling Skull, in which he must find a way to escape death. His identity as a haxu'xan is often, though not always, central to the story's plot – as in Nih'a'ca and the Panther-Young-Man where he, identifying as a woman, marries a panther – and, in stories where his gender is highlighted, serves to teach an important cultural, moral, lesson.

The Nih'a'ca tales are still told in Arapaho and Cheyenne communities, as well as others – including LGBTQ organizations – not only for their entertainment value but for the lessons they offer on personal responsibility and the proper respect and treatment to be shown to others. Like the trickster figures of other nations, Nih'a'ca is often depicted as, or associated with, the spider – spinning webs to catch others which often wind up entangling himself.

The Two-Spirit & Nih'a'ca

Two-Spirit is a modern designation, coined as recently as 1990, for the third gender recognized by many Native American nations for centuries before their contact with European immigrants. Because the term is so new, the two-spirit is often, incorrectly, assumed to be a recent 'discovery' made by anthropologists when, actually, European accounts going back to 1775 reference a third gender among North American Native peoples and the oral histories, myths, and legends – like the Nih'a'ca tales – also attest to the long-standing recognition of two-spirits in a given community.

As the term implies, a two-spirit is someone who recognizes both a male and female spirit dwelling within and often, though not always, dresses in the clothes and performs the duties of their opposite biological sex. Because they are understood as both male and female, two-spirits are recognized as possessing especially keen insight and often serve as mediators – in the present as they did in the past – in resolving personal or communal disputes. They were, and are (or can be), also regarded as holy people – "medicine men" and "medicine women" – serving as mediators between the people and the spirit world. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman comments:

The relationship between a holy person and the spirit world is almost that of a personal religion. The first meeting with the spirits becomes the personal myth, and the power of this myth is important for establishing the holy person's credentials with the tribe, on behalf of which his or her skills are used to locate game, find lost objects, and, above all, treat the sick. The holy person can enter a trance at will and journey to the sacred world.

(132-133)

While Nih'a'ca is sometimes depicted as a holy person, he is more often quite the opposite, possessing characteristics such as selfishness, cruelty, and a blatant disregard for cultural norms. Through the Nih'a'ca tales, which frequently conclude with the central character suffering for his misdeeds, higher values including selflessness, kindness, and respect for tradition and the feelings of others are highlighted.

Nih'a'ca, then, usually serves as an exemplar of bad behavior and is given the identity of a two-spirit – in fact, the first two-spirit in the world – because the recognition of the sacred aspect of the two-spirit further emphasizes just how misguided Nih'a'ca's choices and actions can be. The tales themselves are a kind of 'trickster' turning expectations upside down and, in so doing, offer an audience the opportunity for reflection on their own behavior and the possibility of transformation.

Text

The following text is taken from Traditions of the Arapaho (1903) by George A. Dorsey and Alfred L. Kroeber, republished by University of Nebraska Press, 1997. There are over 40 Nih'a'ca tales included in the book of which three are given below as examples of the themes explored in the larger body of work: Nih'a'ca Pursued by the Rolling Skull, Nih'a'ca and the Panther-Young-Man, and Nih'a'ca and the Bear-Women.

Nih'a'ca Pursued by the Rolling Skull

Nih'a'ca was fishing by a hole in the ice. As he fished, it cracked in the ice. Every now and then there was cracking. "I wonder what it is?" he thought, and looked where he heard the sound. But he could not see anything. Suddenly there emerged from the hole in the ice a skull. Nih'a'ca was terrified. He fled as fast as he could.

"I will kill you," said the skull, pursuing him. In vain, Nih'a'ca ran here and there, up and down hill, among the trees, and on the sand; still the skull followed him. "I wish there were a sandy place," said Nih'a'ca. And, sure enough, it was sandy there. The skull barely moved. At last, it rolled through. "I wish it were brushy," said Nih'a'ca. Then there was undergrowth, and the skull was slowed. While it was trying to roll through, Nih'a'ca was already far away. At last, the skull went around. When it had got by, it pursued Nih'a'ca again.

When it had nearly caught him, he said, "I wish there were a mountain!" And a mountain was there. The skull rolled up but grew tired. Halfway up, it rolled back again. Meanwhile, Nih'a'ca had fled far. Three times the skull [rolled up] and rolled back down. The fourth time, it just reached the top and rolled over. Then it rolled on as if thrown. Again, it had almost caught Nih'a'ca. "Oh!" he said, "I wish there were a great fissure in the ground at the spot from which I am running!" Ah, indeed, there extended a great fissure at the place which he had just run from, and the skull was stopped again.

Then it begged him. "After I have crossed over, I will do you no harm," it said. "But – if you do not bring me across, I shall be angry and will kill you. Come, make a bridge for me!" "Well, then," he told it, "Come over!" He put a stick across as a bridge for it. "Hold it firmly!" it said to him. So he held the stick fast and it rolled along it. When it had rolled to the middle, he turned the stick and the skull dropped down into the great crack. As soon as it fell, the earth closed up over it and it never was seen again. Thus, Nih'a'ca succeeded in saving himself.

Nih'a'ca and the Panther-Young-Man

Nih'a'ca lived with his wife and children. He asked his wife: "Are there any young men who come to the tent courting" She told him, "Yes, there is one. His name is Panther-Young-Man." Nih'a'ca dressed himself as a woman and went out for water. The Panther saw and approached him. At first, Nih'a'ca seemed not to notice him. Then he smiled at him. The Panther asked him to marry him and Nih'a'ca consented. So, they were married and lived together.

Nih'a'ca told the Panther, "Only touch me, that will satisfy you." He sent him hunting. Then he went out on the prairie. He saw a rabbit and said, "Come here, my friend, I wish to speak to you." "What do you wish?" asked the rabbit. "I want you for my child. I will keep you and give you food and water." The rabbit consented and Nih'a'ca took him home under his dress.

After a time, when the Panther came home, he said to him, "We are going to have a child." "Good," said the Panther. He continued to go hunting. The rabbit grew fat and Nih'a'ca became tired of caring for him, feeding him and giving him drink. So, he "gave birth" and wrapped the rabbit up closely and laid him on his bed. When the Panther came home, he told him, "We have had a child born to us." "Good," said the Panther, "Is it a boy or a girl?" "A boy," said Nih'a'ca. "That is good," [said the Panther]. "It is very strange in appearance" [said Nih'a'ca], "It looks like a rabbit. It is very fat." "It is well," said the Panther. Then he started out to hunt again but came back behind the tent and listened.

A man from another tent came in and said to Nih'a'ca, "It is very strange. You have been married only a short time and have a child already. How can that be?" "This is how it is," said Nih'a'ca, opening his dress [and showing himself], "This is how I gave birth to a child." When the Panther heard this, he ran into the timber. "Stay there! The woods and brush will be where you will live," Nih'a'ca said to him. Then he said to the rabbit: "You are too fat. You shall have no fat, except on your kidneys, and on your back behind the shoulders. You will run fast and leap and live on the prairie. This I give to you."

Nih'a'ca and the Bear-Women

Nih'a'ca was traveling down a stream. As he walked along on the bank, he saw something red in the water. They were red plums. He wanted them badly. Taking off his clothes, he dived in and felt over the bottom with his hands, but he could find nothing, and the current carried him downstream and to the surface again. He thought. He took stones and tied them to his wrists and ankles so that they should weigh him down in the water. Then he dived again; he felt over the bottom but could find nothing. When his breath gave out, he tried to come up, but could not. He was nearly dead when, at last, the stones on one side fell off and he barely rose to the surface sideways and got a little air.

As he revived, floating on his back, he saw the plums hanging on the tree above him. He said to himself, "You fool!" He scolded himself a long time. Then he got up, took off the stones, threw them away, and went and ate the plums. He also filled his robe with them. Then he went on down the river.

He came to a tent. He saw a bear-woman come out and go in again. Going close to the tent, he threw a plum so that it dropped in through the top of the tent. When it fell inside, the bear-women and children scrambled for it. Then he threw another and another. At last, one of the women said to her child: "Go out and see if that is not your uncle Nih'a'ca." The child went out, came back, and said, "Yes, it is my uncle Nih'a'ca." Then Nih'a'ca came in. He gave them the plums and said, "I wonder that you never get plums, they grow so near you!" The bear-women wanted to get some at once. He said, "Go up the river a little way, it is not far. Take all your children with you that are old enough to pick. Leave the babies here and I will watch them."

They all went. Then he cut all the babies' heads off. He put the heads back into the cradles; the bodies he put into a large kettle and cooked. When the bear-women came back, he said to them, "Have you never been to that hill here? There were many young wolves there." "In that little hill here?" they asked. "Yes. While you were gone, I dug the young wolves out and cooked them." Then they were all pleased. They sat down and began to eat. One of the children said, "This tastes like my little sister." "Hush!" said her mother, "Don't say that." Nih'a'ca became uneasy. "It is too hot in here," he said, and took some plums and went off a little distance; there he sat down and ate. When he had finished, he shouted, "Ho! Ho! Bear-women, you have eaten your own children!"

All the bears ran to their cradles and found only the heads of the children. At once they pursued him. They began to come near him. Nih'a'ca said, "I wish there were a hole that I could hide in." When they had nearly caught him, he came to a hole and threw himself into it. The hole extended through the hill and he came out on the other side while the bear-women were still standing before the entrance. He painted himself with white paint to look like a different person, took a willow stick, put feathers on it, and laid it across his arm. Then he went to the women.

"What are you crying about?" he asked them. They told him. He said, "I will go into the hole for you" and crawled in. Soon he cried as if hurt and scratched his shoulders. Then he came out, saying, "Nih'a'ca is too strong for me. Go into the hole yourselves; he is not very far in." They all went in but soon came out again and said, "We cannot find him." Nih'a'ca entered once more, scratched himself bloody, bit himself, and cried out. He said, "He has long fingernails with which he scratches me. I cannot drag him out. But he is at the end of the hold. He cannot go back farther. If you go in, you can drag him out. He is only a little farther than you went in last time."

They all went into the hole. Nih'a'ca got brush and grass and made a fire at the entrance. "That sounds like flint striking," said one of the women. "The flint birds are flying," Nih'a'ca said. "That sounds like fire," said another woman. "The fire birds are flying about," Nih'a'ca said, "They will soon be gone by." "That is just like smoke," called a woman. "The smoke birds are passing. Go on, he is only a little farther, you will catch him soon," said Nih'a'ca.

Then the heat followed the smoke into the hole. The bear-women began to shout. "Now the heat birds are flying," said Nih'a'ca. Then the bears were all killed. Nih'a'ca put out the fire and dragged them out. "Thus one obtains food when he is hungry," he said. He cut up the meat, ate some of it, and hung the rest on branches to dry. Then he went to sleep.

While he was asleep, the coyotes and wolves came. They ate all his meat; and the mice came and cut his hair off short and ate all of his robe excepting a small piece on which he was lying. When he woke up in the morning, he found all his meat gone and his hair short. He began to pick up the small pieces of fat and meat that lay scattered about, gathering them into his scrap of a robe. Then he made a fire and sat down in front of it to eat the leavings. Suddenly, a spark fell on his skin. Nih'a'ca jumped up, scattering all of his meat that remained.