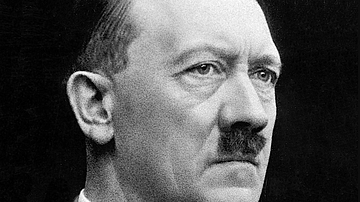

The policy of appeasement towards the demands of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) regarding Nazi Germany's territorial expansion ultimately failed when the Second World War (1939-45) began. The reasons appeasement was adopted by Britain and France through the 1930s included their horror of repeating the First World War (1914-18), their military weakness, the isolationist policy of the USA, a lack of trust in the USSR as an ally, and Hitler's step-by-step expansion, which he always presented as being his last demand. Hindsight has shown appeasement did not work, but it did at least buy time for Britain and France to rearm, even if this opportunity was not fully exploited by either country.

Hitler's Land Grabs

Adolf Hitler became the leader of Nazi Germany in 1933 and pursued an aggressive foreign policy of absorbing neighbouring territories and states. Hitler stated in his book Mein Kampf, published in 1925, that he intended to conquer Europe and gain Lebensraum ('living space') for the German people. He also made countless speeches promising the German people he would overturn the humiliating losses and restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles that formally concluded WWI, which Germany had lost. He then put these ideas into practice in a series of land grabs. Despite all this, the leaders of Britain and France, in particular, remained convinced that Hitler's latest territorial demand would be his last. The policy of appeasement was pursued, that is giving in to Hitler's demands to avoid a terrible repetition of WWI. The result of the policy was that Hitler was permitted to take back the Saar region (1935), remilitarise the Rhineland and begin rearming Germany (1936), absorb Austria into the Third Reich (1938), and then, after the Munich Conference, take over the Czech Sudetenland (1938). Only when Hitler threatened the invasion of Poland in 1939 did Britain and France finally make a stand. Why had Britain and France been passive for so long against Hitler? The answer is complex, with historians continuing to debate the weight of each of several arguments as to why appeasement was adopted.

The Attractions of Appeasement

The reasons Britain and France pursued a policy of appeasement towards Hitler include the following:

- Neither state wanted to repeat the horrors of WWI.

- Neither state was militarily prepared for a war with Germany.

- Delaying a confrontation gave more time for rearmament.

- The isolationist policy of the United States removed a valuable ally against Hitler.

- The weakness of the League of Nations left Britain and France alone to face Hitler.

- The USSR was not considered trustworthy or a militarily useful ally.

- There was a certain sympathy with Germany that it had been too harshly treated after WWI.

- Small regions and states in Central Europe were not considered worth going to war over.

- Hitler was skilled at diplomacy, convincing leaders he would be satisfied with his latest demand and so finally stop his aggressive land grabs.

The Horrors of War

The First World War had been a war like none other in history: 7 million people were killed and 21 million seriously injured. According to the historian F. McDonough, "the total estimated cost of the war has been put at £260,000 million" (43). Both the prime minister of Britain Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940) and France's prime minister Edouard Daladier (1884-1970) had personally experienced the horrors of the war. Ordinary people also remembered all too well the terrible costs of war in ruined lives. As Rab Butler (1902-1982), the British under-secretary of state for foreign affairs, notes:

…if you want to get the record straight the real reason for not standing up in 1938 was the absolute saturation of the country in peace propaganda…the defence hadn't been re-started and the public was pacifist-minded and the Commonwealth was divided, which it wasn't in 1939, and American opinion was not with us at the time of Munich.

(Holmes, 67)

Politicians and diplomats wanted to avoid war, as seen in the idea of creating in 1919 the League of Nations to foster world peace and such initiatives as the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, where governments promised to reject warfare as a tool of foreign policy, and the 1932 World Disarmament Conference in Geneva. Ordinary people's views were reflected and shaped not only by these actions of their politicians but also via the arts, with a raft of anti-war films, novels, and poems produced in the interwar years.

The Problem of Rearmament

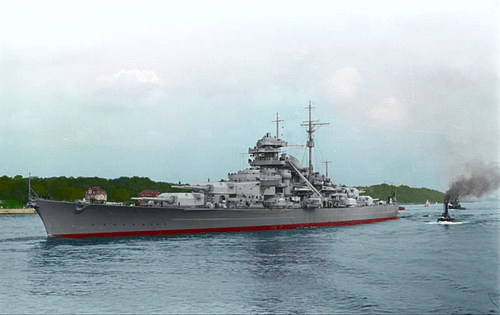

The fact that Germany had been greatly restricted in terms of its armed forces by the Treaty of Versailles convinced many that their own rearmament was not necessary, or, at least, not urgent. Even though Hitler repudiated the treaty and began rearmament in the mid-1930s, Germany was still a long way behind both Britain and France. Britain, in particular, pursued a policy of allowing Hitler to rearm but limiting the process. The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, for example, stipulated that the German navy should never be bigger than around one-third that of the British navy. What was not realised was that numbers were not everything. If another world war happened it would be a much more mechanised and therefore mobile war; no longer would warfare be about who had the most infantry, most ships, or best defences. Future victors would be those who deployed tanks, ships, and aircraft most efficiently.

Rearmament also came at a cost to a nation's economy, and this in a period, after the Great Depression of 1929, which presented many difficulties to those in charge of national budgets. The 1930s served a bitter economic cocktail with such unpalatable ingredients as "a collapse of world trade, unstable currencies, unemployment, agricultural depression and mounting debts" (McDonough, 46). Spending money on arms became a low priority, often by necessity. The appeasers did eventually increase spending on rearmament. In France, for example, the spending on arms trebled in 1938-9, although most of this went into the defensive Maginot Line on the Franco-German border.

Britain & France Alone

The League of Nations had proved itself to be inadequate when it came to aggressor states attacking weaker states. This weakness was particularly evident when Japan invaded Chinese Manchuria in 1931 and Italy invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935. Hitler's aggression also failed to rouse any meaningful response from the League. Crucially, the United States did not join the League and pursued an isolationist policy throughout this period. The president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), went so far as to condemn acts of international aggression, but Congress was passing act after act through the 1930s specifically designed to keep the USA neutral and out of any future war. Without support from the USA, Britain and France felt standing up to Hitler was simply too risky a policy.

The USSR, a Communist country since 1917, was viewed with great suspicion, and since its leader Joseph Stalin (1878-1953) had brutally purged its armed forces, it was not considered militarily powerful enough to provide meaningful support against Hitler. In short, then, the League was essentially Britain and France when it came to facing aggressive states.

Chamberlain remained adamant regarding his anti-Stalin position. Daladier, who served three terms as prime minister, had once been a radical socialist, but he feared the rise of communism at home and abroad – he would later dissolve the French Communist Party. Daladier and Chamberlain, although standing alone, did not even trust each other. French governments had long been trying to get a commitment from Britain regarding army divisions that would fight on the Continent but without success. Britain was not convinced of France's wholly defensive attitude to protecting its frontiers and was wary of pushing Hitler into signing his own treaty of mutual defence with Fascist Italy.

Small Countries Far Away

Hitler's initial acts against international law were often excused as Germany simply retaking what was by rights its own territory, what had been removed by the Treaty of Versailles, which many thought had been too harsh to start with. The Saar region had been removed from Germany after WWI and, similarly, a demilitarisation had been imposed in the German Rhineland. Even Austria could be considered Germany's own backyard, certainly in terms of culture and language, and so the Anschluss (union of Germany and Austria) seemed a weak point to go to war over. This argument was made by the British press and by the politician Lord Lothian, who said, "The Germans…are only going into their own back garden." (Hite, 396). Rigged plebiscites indicating a population's willingness to become a part of 'Greater Germany' eased Western consciences. There was the reality that the British and French people could see little purpose in fighting for the defence of a country far away from their own daily lives. As Chamberlain famously stated in a BBC radio broadcast during the Czech crisis:

How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing.

(McDonough, 77)

Chamberlain also realised the futility of the situation since neither Britain nor France could offer Czechoslovakia any practical military help. Chamberlain noted in his diary in March 1938:

You have only to look at the map to see that nothing France or we could do could possibly save Czechoslovakia from being overrun by the Germans, if they wanted to do it. The Austrian frontier is practically open…Russia is 100 miles away. Therefore we could not help Czechoslovakia – she would simply be a pretext for going to war with Germany.

(Hite, 397).

Hitler's Shifting Diplomacy

Hitler managed to convince Chamberlain and Daladier that his latest demand would be his last, what he really wanted was world peace, he said. Hitler's public messages were confusing. For example, the German leader signed a non-aggression pact with Poland in January 1934. Hitler also signed a promise to Chamberlain that Germany and Britain would never go to war. Hitler had a habit, though, of saying one thing and doing another. In just one clear example, Hitler stated in 1934 that he had no intention of merging Austria into the Third Reich and then did just that in 1938.

Germany's expansion had been a step-by-step process, and it is only with hindsight that the passive response to each of them was shown to be the entirely wrong policy. It was true, though, that each time the Great Powers gave in to Hitler, his position at home was strengthened, and he was emboldened to try ever more ambitious gambles. According to Albert Speer (1905-1981), Germany's future armaments minister, Hitler's followers after the 1938 Munich Agreement when Germany gained the Sudetenland entirely through diplomacy were "now completely convinced of their leader's invincibility" (169). Appeasement was ultimately based on the belief that Hitler would be reasonable and stop conquering his neighbours of his own accord, but this rather naive idea was finally shattered when the Nazi leader reneged on the Munich Agreement and invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

Opposition to Appeasement

Although both Chamberlain and his predecessor as prime minister, Stanley Baldwin (1867-1947), as well as other key government figures like Lord Halifax (1881-1959), the foreign minister, strongly promoted appeasement, there were important voices who protested at the policy. The UK opposition, the Labour Party, and figures like Winston Churchill (1874-1965) were in favour of an alliance with the USSR and taking a tough stance against Hitler. Churchill also led the calls for rearmament. In addition, Anthony Eden (1897-1977) resigned from his position as foreign minister in 1938 over the policy of appeasement.

In France, there had been a series of weak governments throughout the 1930s. Indeed, the French people endured 16 coalition governments between 1932 and 1940. There were voices that called for a more aggressive stance against Hitler, but these were a minority. The French government very much left Britain to take the lead in negotiations with Hitler, especially running up to and including the Munich Agreement. The primary focus of the French government seems to have been to maintain good relations with Britain to ensure that country was France's ally in any future war.

Opposition to appeasement did steadily grow. Many of those who had previously advocated appeasement began to change their minds after the Kristallnacht ('Night of Broken Glass'), the pogrom against Jews in Germany and Austria on 9-10 November 1938. An opinion poll in Great Britain revealed that 70% of the population was shocked at the attack and wanted to cut off diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany. The Federation of University Conservatives voted that appeasement should end. The former prime minister Lloyd George (1863-1945) now publicly stated that the policy of appeasement "lacked courage". In July 1939, 76% of the voters in a British opinion poll were in favour of using force if Hitler tried to take territory from Poland. The national mood, certainly in Britain, had changed.

Failure: War Breaks Out

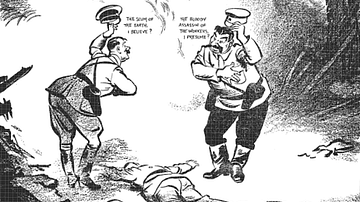

International diplomacy took a turn in an entirely new direction in the summer of 1939. The Nazi-Soviet Pact, also called the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact after the respective foreign ministers of the USSR and Germany, was signed in August 1939. Actually a series of agreements, the pact was a non-aggression agreement between Germany and the USSR, which had secret protocols that divided Central and Eastern Europe into spheres of influence. Poland was to be divided down the middle. Hitler could now attack Poland and then the Low Countries and France without having to fight at the same time an Eastern front with the USSR. Stalin, meanwhile, gained the right to control the Baltic states, Bessarabia, and Finland; he also avoided becoming involved in a war with Germany and so won valuable time for rearmament.

In August, both Britain and France made it clear to Hitler that the policy of appeasement was finished and they would not allow Germany to invade Poland. The Nazi leader, with the USSR now out of the way, did just that on 1 September 1939. Britain and France declared war on Germany two days later. WWII had begun.

With hindsight, the policy of appeasement was shown to be folly since Hitler was, in the end, determined to take over the whole of Europe. However, it is important to note, as the historian A. J. P. Taylor does, that "When the policy of Munich failed, everyone announced that he had expected it to fail…In fact, no one was as clear-sighted as he later claimed to have been" (232-3). Hitler himself may not have had a very clear plan of just how he was going to expand the Third Reich, but the policy of appeasement certainly gave him golden opportunities to achieve his aims through a mix of bluff, bullying, and deft diplomacy. The ultimate cost of appeasement was another terrible world conflict, with far more casualties, both military and civilian, than had ever been seen before.