Caesarea Maritima was located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Built from the ground up in 22-10 BCE by Rome's client king, Herod the Great (r. 37-4 BCE), its location in relation to ship traffic and proximity to historical trade routes indicates a purposeful plan to capture income, making Caesarea a commercial gateway to the West.

Major Players

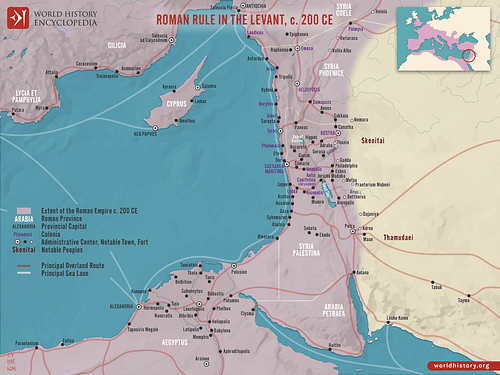

The context for Caesarea's existence lies in Rome's rivalry with Parthia: Rome's ablest competitor. With the defeat at the Battle of Carrhae, 53 BCE, and retreat from Media in 36 BCE, the failure to take Parthia's lucrative northern silk routes through Mesopotamia caused Rome to sue for peace in 20 BCE. As a result, Rome's efforts to round out its dominance in the Mediterranean Sea and the Near East took on a commercial tone. In an attempt to control the lucrative southern east/west trade routes through Arabia and the Red Sea, Caesarea would serve as the springboard. As a key hub in the Eastern trade network of ancient Rome, Caesarea's connections to major players in the early centuries of the first millennium would include Gaza, Petra, Sidon, Tyre, Alexandria, and consumer cities like Bostra. Further afield were the commercial centers of Antioch and Patara.

As a major commercial center in the northern areas of the Mediterranean, Antioch benefited from its location at the western terminus of the Silk Road of Mesopotamia. Besides being a major center of wine and olive oil production and the fulling of cloth products, Antioch played a major role in the distribution of silk from China, lapis lazuli from ancient Afghanistan, dye-works from the Levant, and weaved silk from Damascus.

West of Antioch, on the southern coast of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), was the coastal city of Patara, providing export service. As evidence for the traditional production of agricultural goods and animal husbandry in Anatolia reaches back to the first centuries of the 2nd millennium BCE, the production of Anatolian copper, gold, silver, iron, and lead was documented by Pliny and Strabo. As James Muhly adds:

Anatolia is a land blessed with abundant natural resources, including a wealth of mineral deposits and abundant forests, the two elements necessary for a major metal industry. Recent calculations provide the following figures: 415 major copper-rich zones, more than 136 complex lead-zinc-copper ore deposits, and almost 200 silver-lead deposits, as well as numerous deposits of gold, zinc, antimony, arsenic, and iron. (858-59)

Modern surveys also confirm that, from 3000 BCE to the Ottoman period, Anatolia was an important producer of copper and possibly tin, essential ingredients of bronze.

Then, sharing the eastern coast of the Mediterranean are the two Phoenician city-states of Sidon and Tyre. As Caesarea was built over the ruins of Straton's Tower - named after King Straton I (r. 365-352 BCE) of Sidon - Strabo reports it had its own "station for vessels" (16.2.27). With its location in the midst of shipping and trade routes north of Alexandria and 120 km between Gaza and Sidon, Straton's Tower reflects Sidon's scale of commercial influence. Once providing ships and goods for Persia, Sidon was also an important manufacturer of luxury goods such as glass, dyes, and embroidered garments. Just south of Sidon, the island of Tyre was also a commercial powerhouse. Besides its famous purple-dyed cloth, according to the biblical account in 1 Kings 7:13-45, Solomon sought help from Tyre to manufacture and furnish bronze finished products for the temple.

Though their spheres of commercial influence were reduced with the control of the Phoenician coast by the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), then by the Romans, Sidon, and Tyre would continue to play a part in the overall network of trade in the Eastern Mediterranean. Conversely, while Tyre and Sidon were known for their finished products, west of the Nile on the northern coast of Africa, Alexandria shipped goods from Egypt. Besides the bulk manufacturing and export of textiles and papyrus, with Rome as its main consumer, Egypt commonly shipped its oil and grain products aboard the famous Alexandrian ships. One such ship, the Isis, as described by Lucian, had a length of 55 meters (180 ft) and a beam of 14 meters (45 ft); with a cargo hold depth of 13.5 meters (44 ft), it could carry 1200 tons of product.

Finally, within Caesarea's direct orbit were the important cities of Gaza, Petra, and Bostra. Gaza served as a conduit to Western markets, receiving goods from Africa, Arabia, India, and Indonesia, the most lucrative of which would have been pepper and frankincense. Gaza was one of the first cities to come under Caesarea's direct control when Augustus (r. 31 BCE to 14 CE) granted it to Herod in 30 BCE. However, as the Nabateans of Petra were major traders and middlemen for goods coming from the East through Arabia and the Red Sea by way of their port Leuce, Roman interest in Gaza, Petra, and Red Sea connections would be fully realized when the Roman emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) annexed the Nabatean Kingdom as the Provincia Arabia in 106 CE. In addition, important consumer cities within Caesarea's regional neighborhood would include Jerusalem, Samaria, and Bostra. For Rome – perhaps to cut out Nabatean middlemen – Bostra's commercial importance would be elevated when it later usurped Petra as the trading center of the region to become the Roman capital of Arabia, after which a road was quickly constructed to connect Bostra to the Red Sea.

A City Built for Trade

With connections to major players of trade, perhaps the most important commercial center for Rome in the Eastern Mediterranean was the port city of Caesarea Maritima. While we normally think of city growth in terms of incremental expansion and development, the remarkable thing about Caesarea is the city was built ready for habitation. The infrastructure of Caesarea Maritima included paved streets, waterworks, a temple, palaces, an amphitheater, a theatre, and fundamental to the city's purpose, a colossal harbor. However, though Herod built the city/harbor complex, Rome took early steps to take control. As Barbara Burrell et al. point out, in 6 CE, after Herod's death, his palace "became the official residence of the Roman governor, and his kingdom became a Roman province, with Caesarea as its main port and administrative capital" (56). Moreover, Rome's long-term presence is evident with a recent find at the palace of "two column-shaped pedestals with inscriptions honoring four Roman procurators that date from the 2nd century to the early 4th century CE" (Netzer, 112).

Then, adjoining Caesarea, as trade between the littoral nations of the Mediterranean was accomplished largely by sea, Herod's harbor was an essential arm servicing the city. Moreover, while the city was built to serve Rome's commercial interests, it served Rome's military concerns as well; consequently, the artificial harbor, with no natural bay or promontory to build on, was built like a fortress at sea. Supporting a superstructure of towers, curtain walls, and battlements, using blocks weighing up to 50 tons, its breakwaters (moles) were laid out on a circular course to mitigate erosion. Corresponding with Flavius Josephus' description of the harbor as a "circular haven" (Antiquities, 15.9.6) of the two 30.5-meter (100-ft) wide moles, the southern arm extended 305 meters (1000 ft) west out to sea as it curved north 488 meters (1600 ft). The northern mole also extended 305 meters (1000 ft) west. Both arms terminated at the harbor's northwestern 18-meter (60-ft) wide entrance. Housing nearly 40 acres of water; in comparison, the medium-sized port, Leptis Magna, upgraded by Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) at the end of the 2nd century CE, contained 25 acres. The harbor was, therefore, certainly built to receive mass goods. Vessels of all types and sizes plied the haven: from warships to huge grain ships and larger stone and wine carriers to the smaller merchant galleys.

Connections

Since common travelers in ancient times hitched their rides on merchant vessels, the New Testament account of the water portion of the journeys of Paul the Apostle helps identify some major hubs and trade routes in the Mediterranean and Caesarea's connections to them.

Within the context that Syria and Anatolia were dominated by Rome by 63 BCE, on the first leg of his first journey to Asia, Paul boarded a ship loaded with goods from Antioch heading west for the southern coast of Anatolia. Conversely, on the last leg of his third journey, Paul would leave Patara, also on Anatolia's southern coast, for Caesarea. Consequently, as Anatolia provided its own agricultural needs and received luxury goods from Antioch, with the southeastern Mediterranean's agrarian appetite satisfied – courtesy of Alexandria – the goods loaded at Patara for Caesarea were, with Anatolia's prodigious metal production, likely of a metal nature shipped in ingot form. Once the ship from Patara reached the Phoenician coast, indicative of successive servicing, its first stop would be at Tyre, followed by Ptolemais, before final distribution at Caesarea. As Tyre was also known for its finished metal products, and "Caesarea had a license from Rome to mint bronze coins which were used as a means of exchange in the area's rapidly developing economy", such demand for this kind of production again suggests a metal load from Anatolia (Bull, 27).

Finally, also reflecting Caesarea's wider role in Mediterranean trade, as he left Caesarea on his last journey as a prisoner headed for Rome, Paul boarded an Adramyttium ship from western Anatolia for Myra on Anatolia's southern coast. After leaving Caesarea, the ship stopped at Sidon, a short journey north on its way to Myra, a grain storage center, which indicates it likely added Sidon's finished products to merchandise it was already carrying, possibly ivory or tortoiseshell from Africa or papyrus from Egypt or spices and incense from the east. At Myra, Paul would be transferred to an Alexandrian ship, loaded with grain, for Rome.

With respect to Gaza, Petra, and Bostra, not only did Caesarea own Gaza's markets and worked cooperatively with Alexandria but it also captured trade flows from Petra with its location en route to Gaza. As Gary Young points out, incense was, in fact, carried from Petra by road to Gaza. By owning Gaza, with its diverse markets, Caesarea was placed in a position to dominate not only sea trade but also overland trade to consumer cities inland, like Bostra. In the case of Bostra, with the Legio III Cyrenaica stationed there, as part of Augustus' program to colonize the Roman Empire with Roman army veterans, it would make sense for retiring personnel to settle there after years of personal and commercial interaction within their geographical milieu. As mentioned, the importance of Bostra to Rome is reflected in the fact it usurped Petra as the capital of Roman Arabia.

A Strategic Location

During the period around 200 BCE, pearls, gems, tortoise shells, and silk were trans-shipped west from China by Indian merchants. Nard, costus, cinnamon, ginger, and pepper all came to the Mediterranean by the overland caravan route through northwest India, Afghanistan, and Iran to Seleucia, near modern-day Baghdad, where it followed routes along the Tigris and Euphrates to northern Mesopotamia, which the Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE) came to control. However, from there, it split in three directions: south to the ports of Tyre and Sidon, west to Antioch, or on to Asia Minor to reach the sea at Ephesus. A second route involved loading ships at India's northwest ports, which coasted west and then turned up the Persian Gulf to unload at its head. From there, camels took the merchandise to Seleucia. A third route was all by water, where vessels left India's northwestern ports for the southern shores of Arabia, where they unloaded to Greek craft for the voyage up the Red Sea through Egypt. There, they were sold, processed, and then shipped out of Alexandria to all parts of the Mediterranean.

However, during the early Augustan period, there was a dramatic increase in Eastern items going west to Rome: silk, decorated cotton, shells, tortoiseshell, coral, ivory, nard, aloe, frankincense, myrrh, and spices like pepper, cinnamon, and cassia. In addition, goods coming from southern China also found their way west via the Red Sea. As Roberta Tomber mentions, "In the complex network of regions it is the Red Sea that served as a funnel for goods from the East to the Roman Empire." (57). It was this lucrative market that Rome wanted a part of. Besides evidence of Nabatean presence in Rome's harbor town of Puteoli in 2003, on a Farasan island at the southern end of the Red Sea, archaeologists found an inscription of dedication to the emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE), mentioning the Legio II Traiana Fortis, a legion Trajan created. While it is likely that the Roman presence at the Farasan archipelago was a detachment of the main legion in Egypt, this find represents continuing Roman interest and possible expansion in the Red Sea:

Trajan initiated a period of Roman expansion in the Red Sea that had important commercial consequences. This policy was also consistently pursued by his successors, probably reaching its peak under Marcus Aurelius; it provided the right context for Roman commercial expansion in the East. (Nappo, 71)

Consequently, in their desire to enlarge their commercial network in the Near East, yet limited to the southern east/west trade routes, as Rome sought to control the Egyptian and African markets and the all-important trade routes through Arabia and the Red Sea, Caesarea was well placed to make it a gateway to the West.

Set on the eastern Mediterranean coast between Egypt to the south, and the Phoenician port cities of Tyre and Sidon to the north, the strategic placement of Caesarea with respect to commercial traffic reveals a purposeful design to capture income. First, being on the coast, just south of Tyre, Caesarea now had access to the caravan routes that led north and south between Tyre and Egypt. Then, as merchandise from Egypt and Africa traveled north by ship up the eastern seaboard for dispersal throughout the Mediterranean, Caesarea's expansive harbor was convenient for vessels moving north from Alexandria. Finally, with Rome's control of the Arabian and Red Seas, and, as mentioned, Caesarea's control of Petra and ownership of Gaza, Caesarea now had access to the products that Gaza received from the East as well as the products of southern Arabia, such as the lucrative frankincense carried by camel from Petra to Gaza.

Conclusion: Not All Roads Lead to Rome

Though evidence is beginning to reveal extensive commercial development within the whole of the Mediterranean at the turn of the first millennium, and though Rome was still the major draw for commercial activity within the empire, there are important exceptions. For one, the Roman legionaries and auxiliaries were garrisoned throughout the Mediterranean and would have consumed food and material goods. Then, with 300,000 veterans to find land for, Augustus established 75 colonies. 28 were started in Italy, and the rest were in Roman Gaul, Spain, Greece, Africa, Macedonia, Syria, and Anatolia.

All these generally small settlements – usually a couple of thousand veterans, growing perhaps into a city of 10-15,000 – helped the urbanization and Romanization of the empire. ... As the colonies became established, they developed a competitive pride in being Roman; local aristocracies vied to become Roman in clothes, deed and name. (Rodgers, 86-87)

In the case of Bostra, this paradigm of colonial growth is indicated in the East with Bostra's station of the Legio III Cyrenaica and promotion as the capital of Roman Arabia under the name Colonia Bostra. Moreover, while the refining and reprocessing of Eastern goods in Italy is known, as Young mentions:

It is probable that many of the goods which were finally purchased for consumption in Rome or in other markets throughout the empire had undergone some similar form of reprocessing since their arrival in the east. This is very important to bear in mind, as it implies that the bulk of money that was spent on goods may very well have gone not to foreign traders or ‘middlemen' but rather to those who traded in and reprocessed the goods within the empire itself. Once they had undergone this processing, these goods were then conveyed to the final point of sale, which could have been anywhere within the empire itself. (23)

Therefore, not all bulk or reprocessed products went west to Rome but were manufactured and traded in all directions. Caesarea would have played a part in this, thus making it a busy center of commerce and, like with its mint, a reprocessing center as well. No doubt, Caesarea initially planned to service a large area, and not all ivory, tortoiseshell, oil, grain, textiles, and papyrus coming out of Africa and Egypt or the lucrative goods from the East would have gone to Rome. Besides goods going to active and retired military personnel throughout the Mediterranean, as the eastern Roman provinces began to mirror Rome in structure and taste, the consumption of the same goods increased. Moreover, the unloading of cargo from Patara at Tyre and Caesarea for distribution in the Eastern Mediterranean region shows the flow of trade was not limited to Eastern, African, and Egyptian goods moving north and west but flowed interactively. Consequently, even as Caesarea was actively sending and receiving goods from Anatolia, as the Eastern Mediterranean region began to develop its own commercial network, Caesarea was in a position to interact with it in a significant way, thus implementing a network of trade for Rome that began to move in all directions.